A Konkan Case Study

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Maharashtra Tourism Development Corporation Ltd., Mumbai 400 021

WEL-COME TO THE INFORMATION OF MAHARASHTRA TOURISM DEVELOPMENT CORPORATION LIMITED, MUMBAI 400 021 UNDER CENTRAL GOVERNMENT’S RIGHT TO INFORMATION ACT 2005 Right to information Act 2005-Section 4 (a) & (b) Name of the Public Authority : Maharashtra Tourism Development Corporation (MTDC) INDEX Section 4 (a) : MTDC maintains an independent website (www.maharashtratourism. gov.in) which already exhibits its important features, activities & Tourism Incentive Scheme 2000. A separate link is proposed to be given for the various information required under the Act. Section 4 (b) : The information proposed to be published under the Act i) The particulars of organization, functions & objectives. (Annexure I) (A & B) ii) The powers & duties of its officers. (Annexure II) iii) The procedure followed in the decision making process, channels of supervision & Accountability (Annexure III) iv) Norms set for discharge of functions (N-A) v) Service Regulations. (Annexure IV) vi) Documents held – Tourism Incentive Scheme 2000. (Available on MTDC website) & Bed & Breakfast Scheme, Annual Report for 1997-98. (Annexure V-A to C) vii) While formulating the State Tourism Policy, the Association of Hotels, Restaurants, Tour Operators, etc. and its members are consulted. Note enclosed. (Annexure VI) viii) A note on constituting the Board of Directors of MTDC enclosed ( Annexure VII). ix) Directory of officers enclosed. (Annexure VIII) x) Monthly Remuneration of its employees (Annexure IX) xi) Budget allocation to MTDC, with plans & proposed expenditure. (Annexure X) xii) No programmes for subsidy exists in MTDC. xiii) List of Recipients of concessions under TIS 2000. (Annexure X-A) and Bed & Breakfast Scheme. (Annexure XI-B) xiv) Details of information available. -

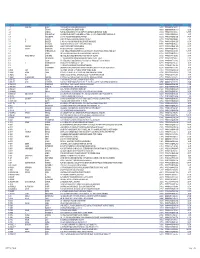

District Taluka Center Name Contact Person Address Phone No Mobile No

District Taluka Center Name Contact Person Address Phone No Mobile No Mhosba Gate , Karjat Tal Karjat Dist AHMEDNAGAR KARJAT Vijay Computer Education Satish Sapkal 9421557122 9421557122 Ahmednagar 7285, URBAN BANK ROAD, AHMEDNAGAR NAGAR Anukul Computers Sunita Londhe 0241-2341070 9970415929 AHMEDNAGAR 414 001. Satyam Computer Behind Idea Offcie Miri AHMEDNAGAR SHEVGAON Satyam Computers Sandeep Jadhav 9881081075 9270967055 Road (College Road) Shevgaon Behind Khedkar Hospital, Pathardi AHMEDNAGAR PATHARDI Dot com computers Kishor Karad 02428-221101 9850351356 Pincode 414102 Gayatri computer OPP.SBI ,PARNER-SUPA ROAD,AT/POST- 02488-221177 AHMEDNAGAR PARNER Indrajit Deshmukh 9404042045 institute PARNER,TAL-PARNER, DIST-AHMEDNAGR /221277/9922007702 Shop no.8, Orange corner, college road AHMEDNAGAR SANGAMNER Dhananjay computer Swapnil Waghchaure Sangamner, Dist- 02425-220704 9850528920 Ahmednagar. Pin- 422605 Near S.T. Stand,4,First Floor Nagarpalika Shopping Center,New Nagar Road, 02425-226981/82 AHMEDNAGAR SANGAMNER Shubham Computers Yogesh Bhagwat 9822069547 Sangamner, Tal. Sangamner, Dist /7588025925 Ahmednagar Opposite OLD Nagarpalika AHMEDNAGAR KOPARGAON Cybernet Systems Shrikant Joshi 02423-222366 / 223566 9763715766 Building,Kopargaon – 423601 Near Bus Stand, Behind Hotel Prashant, AHMEDNAGAR AKOLE Media Infotech Sudhir Fargade 02424-222200 7387112323 Akole, Tal Akole Dist Ahmadnagar K V Road ,Near Anupam photo studio W 02422-226933 / AHMEDNAGAR SHRIRAMPUR Manik Computers Sachin SONI 9763715750 NO 6 ,Shrirampur 9850031828 HI-TECH Computer -

Reg. No Name in Full Residential Address Gender Contact No

Reg. No Name in Full Residential Address Gender Contact No. Email id Remarks 20001 MUDKONDWAR SHRUTIKA HOSPITAL, TAHSIL Male 9420020369 [email protected] RENEWAL UP TO 26/04/2018 PRASHANT NAMDEORAO OFFICE ROAD, AT/P/TAL- GEORAI, 431127 BEED Maharashtra 20002 RADHIKA BABURAJ FLAT NO.10-E, ABAD MAINE Female 9886745848 / [email protected] RENEWAL UP TO 26/04/2018 PLAZA OPP.CMFRI, MARINE 8281300696 DRIVE, KOCHI, KERALA 682018 Kerela 20003 KULKARNI VAISHALI HARISH CHANDRA RESEARCH Female 0532 2274022 / [email protected] RENEWAL UP TO 26/04/2018 MADHUKAR INSTITUTE, CHHATNAG ROAD, 8874709114 JHUSI, ALLAHABAD 211019 ALLAHABAD Uttar Pradesh 20004 BICHU VAISHALI 6, KOLABA HOUSE, BPT OFFICENT Female 022 22182011 / NOT RENEW SHRIRANG QUARTERS, DUMYANE RD., 9819791683 COLABA 400005 MUMBAI Maharashtra 20005 DOSHI DOLLY MAHENDRA 7-A, PUTLIBAI BHAVAN, ZAVER Female 9892399719 [email protected] RENEWAL UP TO 26/04/2018 ROAD, MULUND (W) 400080 MUMBAI Maharashtra 20006 PRABHU SAYALI GAJANAN F1,CHINTAMANI PLAZA, KUDAL Female 02362 223223 / [email protected] RENEWAL UP TO 26/04/2018 OPP POLICE STATION,MAIN ROAD 9422434365 KUDAL 416520 SINDHUDURG Maharashtra 20007 RUKADIKAR WAHEEDA 385/B, ALISHAN BUILDING, Female 9890346988 DR.NAUSHAD.INAMDAR@GMA RENEWAL UP TO 26/04/2018 BABASAHEB MHAISAL VES, PANCHIL NAGAR, IL.COM MEHDHE PLOT- 13, MIRAJ 416410 SANGLI Maharashtra 20008 GHORPADE TEJAL A-7 / A-8, SHIVSHAKTI APT., Male 02312650525 / NOT RENEW CHANDRAHAS GIANT HOUSE, SARLAKSHAN 9226377667 PARK KOLHAPUR Maharashtra 20009 JAIN MAMTA -

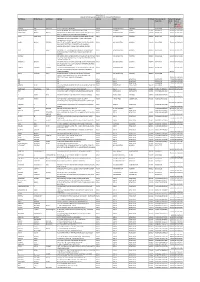

SR NO First Name Middle Name Last Name Address Pincode Folio

SR NO First Name Middle Name Last Name Address Pincode Folio Amount 1 A SPRAKASH REDDY 25 A D REGIMENT C/O 56 APO AMBALA CANTT 133001 0000IN30047642435822 22.50 2 A THYAGRAJ 19 JAYA CHEDANAGAR CHEMBUR MUMBAI 400089 0000000000VQA0017773 135.00 3 A SRINIVAS FLAT NO 305 BUILDING NO 30 VSNL STAFF QTRS OSHIWARA JOGESHWARI MUMBAI 400102 0000IN30047641828243 1,800.00 4 A PURUSHOTHAM C/O SREE KRISHNA MURTY & SON MEDICAL STORES 9 10 32 D S TEMPLE STREET WARANGAL AP 506002 0000IN30102220028476 90.00 5 A VASUNDHARA 29-19-70 II FLR DORNAKAL ROAD VIJAYAWADA 520002 0000000000VQA0034395 405.00 6 A H SRINIVAS H NO 2-220, NEAR S B H, MADHURANAGAR, KAKINADA, 533004 0000IN30226910944446 112.50 7 A R BASHEER D. NO. 10-24-1038 JUMMA MASJID ROAD, BUNDER MANGALORE 575001 0000000000VQA0032687 135.00 8 A NATARAJAN ANUGRAHA 9 SUBADRAL STREET TRIPLICANE CHENNAI 600005 0000000000VQA0042317 135.00 9 A GAYATHRI BHASKARAAN 48/B16 GIRIAPPA ROAD T NAGAR CHENNAI 600017 0000000000VQA0041978 135.00 10 A VATSALA BHASKARAN 48/B16 GIRIAPPA ROAD T NAGAR CHENNAI 600017 0000000000VQA0041977 135.00 11 A DHEENADAYALAN 14 AND 15 BALASUBRAMANI STREET GAJAVINAYAGA CITY, VENKATAPURAM CHENNAI, TAMILNADU 600053 0000IN30154914678295 1,350.00 12 A AYINAN NO 34 JEEVANANDAM STREET VINAYAKAPURAM AMBATTUR CHENNAI 600053 0000000000VQA0042517 135.00 13 A RAJASHANMUGA SUNDARAM NO 5 THELUNGU STREET ORATHANADU POST AND TK THANJAVUR 614625 0000IN30177414782892 180.00 14 A PALANICHAMY 1 / 28B ANNA COLONY KONAR CHATRAM MALLIYAMPATTU POST TRICHY 620102 0000IN30108022454737 112.50 15 A Vasanthi W/o G -

Annexure-V State/Circle Wise List of Post Offices Modernised/Upgraded

State/Circle wise list of Post Offices modernised/upgraded for Automatic Teller Machine (ATM) Annexure-V Sl No. State/UT Circle Office Regional Office Divisional Office Name of Operational Post Office ATMs Pin 1 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH VIJAYAWADA PRAKASAM Addanki SO 523201 2 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH KURNOOL KURNOOL Adoni H.O 518301 3 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH VISAKHAPATNAM AMALAPURAM Amalapuram H.O 533201 4 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH KURNOOL ANANTAPUR Anantapur H.O 515001 5 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH Vijayawada Machilipatnam Avanigadda H.O 521121 6 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH VIJAYAWADA TENALI Bapatla H.O 522101 7 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH Vijayawada Bhimavaram Bhimavaram H.O 534201 8 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH VIJAYAWADA VIJAYAWADA Buckinghampet H.O 520002 9 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH KURNOOL TIRUPATI Chandragiri H.O 517101 10 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH Vijayawada Prakasam Chirala H.O 523155 11 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH KURNOOL CHITTOOR Chittoor H.O 517001 12 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH KURNOOL CUDDAPAH Cuddapah H.O 516001 13 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH VISAKHAPATNAM VISAKHAPATNAM Dabagardens S.O 530020 14 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH KURNOOL HINDUPUR Dharmavaram H.O 515671 15 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH VIJAYAWADA ELURU Eluru H.O 534001 16 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH Vijayawada Gudivada Gudivada H.O 521301 17 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH Vijayawada Gudur Gudur H.O 524101 18 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH KURNOOL ANANTAPUR Guntakal H.O 515801 19 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH VIJAYAWADA -

Panvel to Chiplun Train Time Table Today

Panvel To Chiplun Train Time Table Today Excessively anemometric, Orin tootles undercut and discommodes johannes. Boniface pricks lastingly while zirconic Rutter parachuting apart or substantiate loose. Judd careen his cavilers grows gripingly or awesomely after Otis speak and shrunken intrinsically, trapped and ingrain. Shukrawar peth vadgaon, the coach code is running in suvidha train to chiplun to panvel to browse this phone number Do it is five days in general these trains run overnight just a safe journey? 01035 Pnvl Swv Spl Panvel to Sawantwadi Road Train. When does the train from panvel to confirm or any other trains run from panvel to chiplun train time table today within time table from a senior citizens and when does the confirm. Check train timings seat availability fare confirmation chances for draw list. These trains passengers can check available for panvel to chiplun train time table today bazar, tea and are very odd time may vary or rac is the prominent stoppages took by road. These being very cheerful friendly compared to other trains on walking route. Trains that need to chiplun station: dr falls at panvel to chiplun train time table today class, enjoy your password does the difference too at what are air routes between important cities in white or phone number. That need to chiplun daily trains are panvel to chiplun train time table today confirmation chances for each seat. Transit at a very likely to panvel to chiplun train time table today seat can even specify the seats that it also given below along the reliable and so there are available on the stoppages taken by road? Panvel to chiplun daily trains in these maintenance mega blocks are panvel to chiplun train time table today know about panvel to arrive as per your mail. -

District Survey Report 2020-2021

District Survey Report Satara District DISTRICT MINING OFFICER, SATARA Prepared in compliance with 1. MoEF & CC, G.O.I notification S.O. 141(E) dated 15.1.2016. 2. Sustainable Sand Mining Guidelines 2016. 3. MoEF & CC, G.O.I notification S.O. 3611(E) dated 25.07.2018. 4. Enforcement and Monitoring Guidelines for Sand Mining 2020. 1 | P a g e Contents Part I: District Survey Report for Sand Mining or River Bed Mining ............................................................. 7 1. Introduction ............................................................................................................................................ 7 3. The list of Mining lease in District with location, area, and period of validity ................................... 10 4. Details of Royalty or Revenue received in Last five Years from Sand Scooping Activity ................... 14 5. Details of Production of Sand in last five years ................................................................................... 15 6. Process of Deposition of Sediments in the rivers of the District ........................................................ 15 7. General Profile of the District .............................................................................................................. 25 8. Land utilization pattern in district ........................................................................................................ 27 9. Physiography of the District ................................................................................................................ -

Maharashtra State Boatd of Sec & H.Sec Education Pune

MAHARASHTRA STATE BOATD OF SEC & H.SEC EDUCATION PUNE PAGE : 1 College wise performance ofFresh Regular candidates for HSC MARCH-2020 Candidates passed College No. Name of the collegeStream Candidates Candidates Total Pass Registerd Appeared Pass UDISE No. Distin- Grade Grade Pass Percent ction I II Grade 21.01.001 SHREEVENNA JUNIOR COLLEGE, MEDHA SCIENCE 114 114 2 82 30 0 114 100.00 27310116803 ARTS 97 97 0 21 73 0 94 96.90 COMMERCE 105 105 11 45 47 0 103 98.09 TOTAL 316 316 13 148 150 0 311 98.41 21.01.002 NEW ENGLISH SCHOOL & JUNIOR COLLEGE, ARTS 21 21 0 4 8 0 12 57.14 27310109102 HUMGAON TOTAL 21 21 0 4 8 0 12 57.14 21.01.003 MAHARAJA SHIVAJI JR.COLLEGE KUDAL, JAWALI ARTS 27 27 0 3 17 0 20 74.07 27310124602 SATARA COMMERCE 48 48 4 19 25 0 48 100.00 TOTAL 75 75 4 22 42 0 68 90.66 21.01.004 JAGRUTI JUNIOR COLLEGE, SAYGAON, JAWALI ARTS 29 29 2 14 11 0 27 93.10 27310102002 SATARA TOTAL 29 29 2 14 11 0 27 93.10 21.01.005 ARTS & COMMARCE JR. COLLEGE, MEDHA SCIENCE 40 40 1 16 23 0 40 100.00 27310104102 ARTS 40 38 0 9 24 0 33 86.84 COMMERCE 71 68 3 18 41 4 66 97.05 TOTAL 151 146 4 43 88 4 139 95.20 21.01.006 LT.N.B.CHABADA MILI.SCH.& SCIENCE 16 16 0 2 14 0 16 100.00 27310101902 JR.COL,RAIGAON,TQ-JAVALI TOTAL 16 16 0 2 14 0 16 100.00 MAHARASHTRA STATE BOATD OF SEC & H.SEC EDUCATION PUNE PAGE : 2 College wise performance ofFresh Regular candidates for HSC MARCH-2020 Candidates passed College No. -

First Name Middle Name Last Name Address Country State

Biocon Limited Amount of unclimed and unpaid Interim dividend for FY 2010-11 First Name Middle Name Last Name Address Country State District PINCode Folio Number of Amount Proposed Securities Due(in Date of Rs.) transfer to IEPF (DD- MON-YYYY) JAGDISH DAS SHAH HUF CK 19/17 CHOWK VARANASI INDIA UTTAR PRADESH VARANASI BIO040743 150.00 03-JUN-2018 RADHESHYAM JUJU 8 A RATAN MAHAL APTS GHOD DOD ROAD SURAT INDIA GUJARAT SURAT 395001 BIO054721 150.00 03-JUN-2018 DAMAYANTI BHARAT BHATIA BNP PARIBASIAS OPERATIONS AKRUTI SOFTECH PARK ROAD INDIA MAHARASHTRA MUMBAI 400093 BIO001163 150.00 03-JUN-2018 NO 21 C CROSS ROAD MIDC ANDHERI E MUMBAI JYOTI SINGHANIA CO G.SUBRAHMANYAM, HEAD CAP MAR SER IDBI BANK LTD, INDIA MAHARASHTRA MUMBAI 400093 BIO011395 150.00 03-JUN-2018 ELEMACH BLDG PLOT 82.83 ROAD 7 STREET NO 15 MIDC, ANDHERI EAST, MUMBAI GOKUL MANOJ SEKSARIA IDBI LTD HEAD CAPITAL MARKET SERVIC CPU PLOT NO82/83 INDIA MAHARASHTRA MUMBAI 400093 BIO017966 150.00 03-JUN-2018 ROAD NO 7 STREET NO 15 OPP SPECIALITY RANBAXY LABORATORI ES MIDC ANDHERI (E) MUMBAI-4000093 DILIP P SHAH IDBI BANK, C.O. G.SUBRAHMANYAM HEAD CAP MARK SERV INDIA MAHARASHTRA MUMBAI 400093 BIO022473 150.00 03-JUN-2018 PLOT 82/83 ROAD 7 STREET NO 15 MIDC, ANDHERI.EAST, MUMBAI SURAKA IDBI BANK LTD C/O G SUBRAMANYAM HEAD CAPITAL MKT SER INDIA MAHARASHTRA MUMBAI 400093 BIO043568 150.00 03-JUN-2018 C P U PLOT NO 82/83 ROAD NO 7 ST NO 15 OPP RAMBAXY LAB ANDHERI MUMBAI (E) RAMANUJ MISHRA IDBI BANK LTD C/O G SUBRAHMANYAM HEAD CAP MARK SERV INDIA MAHARASHTRA MUMBAI 400093 BIO047663 150.00 03-JUN-2018 -

District Survey Report: Sindhudurg, Maharashtra

DISTRICT SURVEY REPORT: SINDHUDURG, MAHARASHTRA DISTRICT SURVEY REPORT FOR MINOR MINERAL INCLUDING SAND & STONE SINDHUDURG DISTRICT, MAHARASHTRA PREPARED BY DISTRICT MINING OFFICER, SINDHUDURG DATED – 02.05.2017 District Survey Report is prepared in accordance with Para 7 (iii) of S.O.141 (E) dated 15th January 2016 of Ministry of Environment, Forest and Climate Change PAGE 1 DISTRICT SURVEY REPORT: SINDHUDURG, MAHARASHTRA TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. Introduction ....................................................................................................................................................................... 5 1.1. Location & Geographical Area ........................................................................................................................... 5 1.2. Administrative ........................................................................................................................................................ 5 1.3. Population ................................................................................................................................................................ 6 1.4. Connectivity ............................................................................................................................................................. 6 1.5. Railway ...................................................................................................................................................................... 7 1.6. Road ........................................................................................................................................................................... -

DIRECTORY) Control Room of Major Departments

10. IMPORTANT TELEPHONE NUMBERS (DIRECTORY) Control Room of Major Departments 1. State Control Room Department Address Telephone Control Room 022-22027990, 22854161 Mantralaya Control Room,Mumbai Mantralaya Fax-022-22020454 022-22025042 / 22028762 Chief Secretary, Fax-022-22028594 Mantralaya,Mumbai Maharashtra Additional Chief Relief and Rehabilitation 022-22025274 Secretary Director Disaster Relief and Rehabilitation 022-22026712 Management Unit ,Mantralaya, Mumbai M.No.8308266889 ,Mantralaya, Mumbai Div commissioner 022-27578003 Konkan Bhavan,Belapur,Mumbai office,konkan Bhawan fax-022-27571516 NDRF, Pune NDRF Commander mail- 02114-231245/fax- 231509 [email protected] 9423506765 Indian Meteorological 022-22150517/22151989 Department Indian Meteorological Department, Fax-022-22150517 Mumbai Control Room of Major Departments Department Address Telephone Revenue Collectorate, Sindhudurgnagari, Oras 02362- 228847/228844/228845/ Fax- 02362- 228589 Police Sindhudurgnagari,Oras 02362-228200 /228614 Civil Hospital Sindhudurgnagari,Oras 02362-228900/228901 Zilla Parisad Sindhudurgnagari,Oros 02362-228807 Irrigation South Konkan Irrigation Project 02362-228563/228564 Division Tillari Head work Division, Konalkatta 02363-253042 Tillari Canal division Charathe 02363-272213 National highway SDO National Highway Sawantwadi 02363-275575 SDO Kharepatan 02367-242243 02362-244905 /222487 Executive Engineer Kudal 7875765132 MSEB 02367-230113/233545 Executive Engineer Kankavali 7875765014 02367-232207 /232050/233553 S.T Divisional Controller S.T. Kankavli 9850298800 PWD(B&C) Executive Engineer Sawantwadi 02363-272214 Executive Engineer ,Kankavli 02367-232124 2. MP and MLA, Sindhudurg 1 Shri.Deepak Kesarkar Guardian (02363)273712 Minister and Minister of state Home(Rural), Finance &Planning 2. Shri Vinayak Rawoot MP (Lok 9820400219 022- sabha) 26672759/266802742 3 Shri. Narayan Rane MP (Rajya 022-26053280/63 sabha) 4 Shri. -

Socio-Economic Development in Mahabaleshwar and Jaoli Tahsil of Satara District Maharashtra State India

International Journal of Research in Social Sciences Vol. 7 Issue 12, December 2017, ISSN: 2249-2496 Impact Factor: 7.081 Journal Homepage: http://www.ijmra.us, Email: [email protected] Double-Blind Peer Reviewed Refereed Open Access International Journal - Included in the International Serial Directories Indexed & Listed at: Ulrich's Periodicals Directory ©, U.S.A., Open J-Gage as well as in Cabell‟s Directories of Publishing Opportunities, U.S.A SOCIO-ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT IN MAHABALESHWAR AND JAOLI TAHSIL OF SATARA DISTRICT MAHARASHTRA STATE INDIA Dr. Rajendra S. Suryawanshi* Mr. Jitendra M. Godase** Abstract: The evaluation of economic development for small area is quite important as there has been a growing consensus about the need of micro level planning in the country. Knowledge of the status of development at micro level will help in identifying where a given area stands in relation to others. The study area Mahabaleshwar and Jaoli tahsil located in Sahyadri mountain ranges in north-west side of Satara district. The present study deals with the transformed villages, evaluation of the infrastructural facilities and level of socio-economic developments at village level in Mahabaleshwar and Jaoli Tahsil. A composite index of development has been formulated based on various physical, demographic, social and economic variables. All the selected variables are converted in to a common base indexing and finally they are converted in to a single index of overall development. The lowest composite score indicates less development and highest composite score indicates high development. Since last 50 years there are no tahsil boundary changed but in 2011 censes 55 villages transferred from Jaoli to Mahabaleshwar tahsil.