8. How the Hell Did I End up Teaching?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Milton Friedman on the Wallaby Track

FEATURE MILTON FRIEDMAN ON THE WALLABY TRACK Milton Friedman and monetarism both visited Australia in the 1970s, writes William Coleman he recent death of Milton Friedman Australia, then, was besieged by ‘stagflation’. immediately produced a gusher of Which of the two ills of this condition—inflation obituaries, blog posts and editorials. or unemployment—deserved priority in treatment But among the rush of salutes was a matter of sharp disagreement. But on and memorials, one could not certain aspects of the policy problem there existed Tfind any appreciation of Friedman’s part in the a consensus; that the inflation Australia was Australian scene. This is surprising: his extensive experiencing was cost-push in nature, and (with an travels provided several quirky intersections with almost equal unanimity) that some sort of incomes Australian public life, and his ideas had—for policy would be a key part of its remedy. This was a period of time—a decisive influence on the certainly a politically bipartisan view, supported Commonwealth’s monetary policy. by both the Labor Party and the Liberal Party Milton Friedman visited Australia four times: during the 1974 election campaign.2 The reach 1975, 1981, and very briefly in 1994 and 2005. of this consensus is illustrated in its sway over the On none of these trips did he come to visit Institute of Public Affairs. The IPA was almost shrill Australian academia, or to play any formal policy in its advocacy of fighting inflation first. But the advice role. Instead his first visit was initiated and IPA’s anti-inflation policy, as outlined in the ‘10 organised by Maurice Newman, then of the Sydney point plan’ it issued in July 1973, was perfectly stockbroking firm Constable and Bain (later neo-Keynesian. -

Paul Ormonde's Audio Archive About Jim Cairns Melinda Barrie

Giving voice to Melbourne’s radical past Paul Ormonde’s audio archive about Jim Cairns Melinda Barrie University of Melbourne Archives (UMA) has recently Melbourne economic historian and federal politician Jim digitised and catalogued journalist Paul Ormonde’s Cairns’.4 Greer’s respect for Cairns’ contribution to social audio archive of his interviews with ALP politician Jim and cultural life in Australia is further corroborated in her Cairns (1914–2003).1 It contains recordings with Cairns, speech at the launch of Protest!, in which she expressed and various media broadcasts that Ormonde used when her concern about not finding any trace of Cairns at the writing his biography of Cairns, A foolish passionate university, and asked about the whereabouts of his archive: man.2 It also serves as an oral account of the Australian ‘I have looked all over the place and the name brings up Labor Party’s time in office in the 1970s after 23 years in nothing … you can’t afford to forget him’.5 Fortunately, opposition.3 Paul Ormonde offered to donate his collection of taped This article describes how Ormonde’s collection was interviews with Cairns not long after Greer’s speech. acquired and the role it has played in the development During his long and notable career in journalism, of UMA’s audiovisual (AV) collection management Ormonde (b. 1931) worked in both print and broadcast procedures. It also provides an overview of the media, including the Daily Telegraph, Sun News Pictorial Miegunyah-funded AV audit project (2012–15), which and Radio Australia. A member of the Australian Labor established the foundation for the care and safeguarding Party at the time of the party split in 1955, he was directly of UMA’s AV collections. -

NSSM 204) (1)” of the NSC Institutional Files at the Gerald R

The original documents are located in Box 12, folder “Senior Review Group Meeting, 8/15/74 - Australia (NSSM 204) (1)” of the NSC Institutional Files at the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library. Copyright Notice The copyright law of the United States (Title 17, United States Code) governs the making of photocopies or other reproductions of copyrighted material. The Council donated to the United States of America his copyrights in all of his unpublished writings in National Archives collections. Works prepared by U.S. Government employees as part of their official duties are in the public domain. The copyrights to materials written by other individuals or organizations are presumed to remain with them. If you think any of the information displayed in the PDF is subject to a valid copyright claim, please contact the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library. Digitized from Box 12 of The NSC Institutional Files at the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library I"'- - TOP SEC!tETtSENSITIVE SRG MEETING U.S. Policy Toward Australia (NSSM 204) August 15, 1974 Mrs. Davis TOP SECRB'F-/SENSITIVE NATIONAL ARCHIVES AND RECORDS ADMINISTRATION Presidential Libraries Withdrawal Sheet WITHDRAWAL ID 023486 REASON FOR WITHDRAWAL • • National security restriction TYPE OF MATERIAL • • • Memorandum CREATOR'S NAME . W. R. Smyser RECEIVER'S NAME . Secretary Kissinger TITLE . Australian NSSM CREATION DATE . 08/22/1974 VOLUME . 6 pages COLLECTION/SERIES/FOLDER ID • 039800160 COLLECTION TITLE ...•••• U.S. NATIONAL SECURITY COUNCIL INSTITUTIONAL RECORDS BOX NUMBER • 12 FOLDER TITLE . Senior Review Group Meeting, 8/15/74 - Australia (NSSM 204) (1) . DATE WITHDRAWN . • • • . 10/13/2005 WITHDRAWING ARCHIVIST . GG REDACTED ljJSII'f MEMORANDUM NATIONAL SECURITY COUNCIL ACTION ~OP a}!;;GRET August 22, 19 7 4 MEMORANDUM FOR: SECRETARY KISSINGER OECI.ASSIFIED w/ pott1ona exemple4 E.O. -

Politics, Power and Protest in the Vietnam War Era

Chapter 6 POLITICS, POWER AND PROTEST IN THE VIETNAM WAR ERA In 1962 the Australian government, led by Sir Robert Menzies, sent a group of 30 military advisers to Vietnam. The decision to become Photograph showing an anti-war rally during the 1960s. involved in a con¯ict in Vietnam began one of Australia's involvement in the Vietnam War led to the largest the most controversial eras in Australia's protest movement we had ever experienced. history. It came at a time when the world was divided between nations that were INQUIRY communist and those that were not; when · How did the Australian government respond to the communism was believed to be a real threat to threat of communism after World War II? capitalist societies such as the United States · Why did Australia become involved in the Vietnam War? and Australia. · How did various groups respond to Australia's The Menzies government put great effort into involvement in the Vietnam War? linking Australia to United States foreign · What was the impact of the war on Australia and/ policy in the Asia-Paci®c region. With the or neighbouring countries? communist revolution in China in 1949, the invasion of South Korea by communist North A student: Korea in 1950, and the con¯ict in Vietnam, 5.1 explains social, political and cultural Australia looked increasingly to the United developments and events and evaluates their States to contain communism in this part of the impact on Australian life world. The war in Vietnam engulfed the 5.2 assesses the impact of international events and relationships on Australia's history Indochinese region and mobilised hundreds of 5.3 explains the changing rights and freedoms of thousands of people in a global protest against Aboriginal peoples and other groups in Australia the horror of war. -

Gough Whitlam, a Moment in History

Gough Whitlam, A Moment in History By Jenny Hocking: The Miegunyah Press, Mup, Carlton Victoria, 2008, 9780522111 Elaine Thompson * Jenny Hocking is, as the media release on this book states, an acclaimed and accomplished biographer and this book does not disappoint. It is well written and well researched. My only real complaint is that it should be clearer in the title that it only concerns half of Gough Whitlam’s life, from birth to accession the moment of the 1972 election. It is not about Whitlam as prime minister or the rest of his life. While there are many books about Whitlam’s term as prime minister, I hope that Jenny Hocking will make this book one of a matched pair, take us through the next period; and that Gough is still with us to see the second half of his life told with the interest and sensitivity that Jenny Hocking has brought to this first part. Given that this is a review in the Australasian Parliamentary Review it seems appropriate to concentrate a little of some of the parliamentary aspects of this wide ranging book. Before I do that I would like to pay my respects to the role Margaret Whitlam played in the story. Jenny Hocking handles Margaret’s story with a light, subtle touch and recognizes her vital part in Gough’s capacity to do all that he did. It is Margaret who raised the children and truly made their home; and then emerges as a fully independent woman and a full partner to Gough. The tenderness of their relationship is indicated by what I consider a lovely quote from Margaret about their first home after their marriage. -

The Hidden History of the Whitlam Labor Opposition

Labor and Vietnam: a Reappraisal Author Lavelle, Ashley Published 2006 Journal Title Labour History Copyright Statement © 2006 Ashley David Lavelle and Australian Society for the Study of Labour History. This it is not the final form that appears in the journal Labour History. Please refer to the journal link for access to the definitive, published version. Downloaded from http://hdl.handle.net/10072/13911 Link to published version http://www.asslh.org.au/journal/ Griffith Research Online https://research-repository.griffith.edu.au Labor and Vietnam: a Reappraisal1 This paper argues, from a Marxist perspective, that the shift in the Australian Labor Party’s (ALP) Vietnam war policy in favour of withdrawal was largely brought about by pressure from the Anti-Vietnam War Movement (AVWM) and changing public opinion, rather than being a response to a similar shift by the US government, as some have argued. The impact of the AVWM on Labor is often understated. This impact is indicated not just by the policy shifts, but also the anti-war rhetoric and the willingness of Federal Parliamentary Labor Party (FPLP) members to support direct action. The latter is a particular neglected aspect of commentary on Labor and Vietnam. Labor’s actions here are consistent with its historic susceptibility to the influence of radical social movements, particularly when in Opposition. In this case, by making concessions to the AVWM Labor stood to gain electorally, and was better placed to control the movement. Introduction History shows that, like the British Labour Party, the ALP can move in a radical direction in Opposition if it comes under pressure from social movements or upsurges in class struggle in the context of a radical ideological and political climate. -

Just a Suburban Boy

Cultural Studies Review volume 11 number 2 September 2005 http://epress.lib.uts.edu.au/journals/index.php/csrj/index pp. 221–225 Lindsay Barrett 2005 Just a suburban boy Book Review LINDSAY BARRETT UNIVERSITY OF WESTERN SYDNEY Craig McGregor Australian Son: Inside Mark Latham Pluto Press, North Melbourne, 2004 ISBN 1-86403-288-X RRP $24.95 (pb) Margaret Simons Quarterly Essay: Latham’s World: The New Politics of the Outsiders BlacK Inc., Melbourne, 2004 ISBN 1-86395-197-0 RRP $13.95 (pb) Michael Duffy Latham and Abbott Random House Australia, Milson’s Point, 2004 ISSN 1837-8692 ISBN 1-74051-318-5 RRP $32.95 (pb) Recently I spent some time in hospital. In the midst of one disturbed, dream-filled night I found myself in the bacK of a taxi. The driVer Was Paul Keating, and he Was Wearing a checKed shirt. ‘I’m only doing this, mate’, he said (in the cadence We all know so Well), ‘driVing this taxi, because I want to see what it’s liKe.’ It was the sombre, not the exuberant Keating—the darK prince—and he didn’t smile once. I’d asked him to take me to the location of my childhood home, in inner Sydney, and While he had initially headed in the right direction, as We got closer he began to take an increasingly circuitous route, so that eVen as We appeared to be nearing the destination, at the same time We also seemed to be getting further and further away. And then I Woke up, to the sound of moans and groans, clanging trolleys, and the dim daWn of another anxious day. -

ANNUAL JIM CAIRNS MEMORIAL LECTURE the Role Of

ANNUAL JIM CAIRNS MEMORIAL LECTURE The Role of Government – A Labor View for 2005 Delivered by Julia Gillard Member for Lalor RMIT 23 August 2005 Introduction It is my great pleasure to be here to honour with you the memory of Jim Ford Cairns, Member for Yarra and one of my predecessors as Member for Lalor. Jim Cairns had the courage to dream of a better world. He believed in what he called “long term valuative change”. From the perspective of 2005, when so much that should be at the moral core of Australia’s public life has been corroded, his view that those in public life should inspire us to be better people and aspire to make this nation a better place, seems almost quaint. During a tribute on the ABC following the death of Jim Cairns, his former leader and adversary, Gough Whitlam said about his former deputy leader: “Jim Cairns brought a nobility to the Labor cause which has never been surpassed.” It was a generous tribute. Views sharply vary within and beyond the Labor Party as to the value of Jim’s contribution. We did not share all of his dreams and many doubted the quality of his attempts to implement change. But with a mix of strengths and flaws, he played a role in changing the history of this nation. As Barry Jones – my predecessor and Jim Cairns successor in the seat of Lalor – noted in his maiden speech to the House of Representatives in 1978: 2 [Jim] served as a crusader for great causes – against the Vietnam war and for a more loving, compassionate and cooperative society. -

Ministers for Foreign Affairs 1972-83

Ministers for Foreign Affairs 1972-83 Edited by Melissa Conley Tyler and John Robbins © The Australian Institute of International Affairs 2018 ISBN: 978-0-909992-04-0 This publication may be distributed on the condition that it is attributed to the Australian Institute of International Affairs. Any views or opinions expressed in this publication are not necessarily shared by the Australian Institute of International Affairs or any of its members or affiliates. Cover Image: © Tony Feder/Fairfax Syndication Australian Institute of International Affairs 32 Thesiger Court, Deakin ACT 2600, Australia Phone: 02 6282 2133 Facsimile: 02 6285 2334 Website:www.internationalaffairs.org.au Email:[email protected] Table of Contents Foreword Allan Gyngell AO FAIIA ......................................................... 1 Editors’ Note Melissa Conley Tyler and John Robbins CSC ........................ 3 Opening Remarks Zara Kimpton OAM ................................................................ 5 Australian Foreign Policy 1972-83: An Overview The Whitlam Government 1972-75: Gough Whitlam and Don Willesee ................................................................................ 11 Professor Peter Edwards AM FAIIA The Fraser Government 1975-1983: Andrew Peacock and Tony Street ............................................................................ 25 Dr David Lee Discussion ............................................................................. 49 Moderated by Emeritus Professor Peter Boyce AO Australia’s Relations -

AUSTRALIAN BIOGRAPHY a Series That Profiles Some of the Most Extraordinary Australians of Our Time

STUDY GUIDE AUSTRALIAN BIOGRAPHY A series that profiles some of the most extraordinary Australians of our time Jim Cairns 1914–2003 Politician This program is an episode of Australian Biography Series 7 produced under the National Interest Program of Film Australia. This well-established series profiles some of the most extraordinary Australians of our time. Many have had a major impact on the nation’s cultural, political and social life. All are remarkable and inspiring people who have reached a stage in their lives where they can look back and reflect. Through revealing in-depth interviews, they share their stories— of beginnings and challenges, landmarks and turning points. In so doing, they provide us with an invaluable archival record and a unique perspective on the roads we, as a country, have travelled. Australian Biography: Jim Cairns Director/Producer Robin Hughes Executive Producer Megan McMurchy Duration 26 minutes Year 1999 Study guide prepared by Diane O’Flaherty © Film Australia Also in Series 7: Rosalie Gascoigne, Priscilla Kincaid-Smith, Charles Perkins, Bill Roycroft, Peter Sculthorpe, Victor Smorgon A FILM AUSTRALIA NATIONAL INTEREST PROGRAM For more information about Film Australia’s programs, contact: Film Australia Sales, PO Box 46 Lindfield NSW 2070 Tel 02 9413 8634 Fax 02 9416 9401 Email [email protected] www.filmaust.com.au AUSTRALIAN BIOGRAPHY: JIM CAIRNS 2 SYNOPSIS WHO’S WHO IN POLITICS? Throughout the 1960s and 70s Dr Jim Cairns held a unique position In the Labor Party in Australian public life as the intellectual leader of the political left. GOUGH WHITLAM: Prime Minister of Australia from December 1972 As a senior and influential member of the Whitlam Government, he to November 1975, he was the first Labor prime minister since was involved in many of its achievements and also heavily implicated 1949. -

AUSTRALIAN BIOGRAPHY a Series That Profiles Some of the Most Extraordinary Australians of Our Time

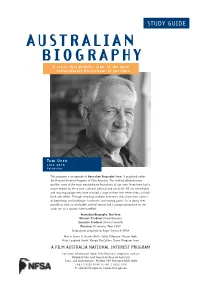

STUDY GUIDE AUSTRALIAN BIOGRAPHY A series that profiles some of the most extraordinary Australians of our time To m Uren 1921–2015 P olitician This program is an episode of Australian Biography Series 5 produced under the National Interest Program of Film Australia. This well-established series profiles some of the most extraordinary Australians of our time. Many have had a major impact on the nation’s cultural, political and social life. All are remarkable and inspiring people who have reached a stage in their lives where they can look back and reflect. Through revealing in-depth interviews, they share their stories— of beginnings and challenges, landmarks and turning points. In so doing, they provide us with an invaluable archival record and a unique perspective on the roads we, as a country, have travelled. Australian Biography: Tom Uren Director/Producer Frank Heimans Executive Producer Sharon Connolly Duration 26 minutes Year 1997 Study guide prepared by Roger Stitson © NFSA Also in Series 5: Charles Birch, Zelda D’Aprano, Miriam Hyde, Ruby Langford Ginibi, Mungo MacCallum, Dame Margaret Scott A FILM AUSTRALIA NATIONAL INTEREST PROGRAM For more information about Film Australia’s programs, contact: National Film and Sound Archive of Australia Sales and Distribution | PO Box 397 Pyrmont NSW 2009 T +61 2 8202 0144 | F +61 2 8202 0101 E: [email protected] | www.nfsa.gov.au AUSTRALIAN BIOGRAPHY: TOM UREN FILM AUSTRALIA 2 SYNOPSIS " Tom says he did not hate the Japanese. Who or what did he hate and struggle against for the rest of his life? Tom Uren, ‘the conscience of Parliament’, is one of the best-known and most-respected Labor politicians of his generation. -

The When, Where, Why and How of the Melbourne Partisan Magazine

The When, Where, Why and How of The Melbourne Partisan Magazine JOHN TIMLIN Fitzroy The Melbourne Partisan, three issues, April-November, 1965. Editors: Laurie Clancy and John Timlin. Contributors, Administration and Helpers: Anonymous, Jim Cairns MHR, Graham Cantieni, Jack Clancy, Laurie Clancy, Manning Clark, Richard N. Coe, Alan Cole, Robert Corcoran, Bruce Dawe, Hume Dow, Beatrice Faust, Raimond Gaita, Fr. J. Golden SJ, Geoff Goode, John Harris, Michael Johnson, Evan Jones, “Mick” Jordan, James Jupp, Tom Kramer, Sam Lipski, Jim Lisle, John Lloyd, Senator Frank McManus, Humphrey McQueen, Brian Matthews, Don Miller, Rex Mortimer, Bishop J. S. Moyes, Hank Nelson, Barry Oakley, Neil Phillips, Neil Phillipson, Rev. David Pope, John Powell, Mrs. L. Rabl, Sir Herbert Read, Virginia Sikorskis Geoff Sharp, John Timlin, Brian Toohey, Tom Truman, Ian Turner, Virginia Sikorskis, Chris Wallace-Crabbe, W.C. Wentworth, E.L. Wheelwright. My association as co-publisher and co-editor of The Melbourne Partisan began after Laurie Clancy in the Melbourne University paper, Farrago, attempted to lay waste the censorship policies of the Menzies and Bolte governments. He wrote reviews under the nom de plume Horace A. Bridgfunt to discuss the many books then banned in Australia. Paperbacks for review were dissected in Hawaii and separate pages mailed to Melbourne in dozens of envelopes. This beat the Customs Department but was too slow so I offered Laurie a solution. Working on the Melbourne waterfront repairing scales and aided by a knowledgeable wharfie mate, a denizen of that notorious Commo front, the International Bookshop, I could sneak through the gates with a few banned volumes.