The Strange Phenomenon of the Footballer's Perfect 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Graham Budd Auctions Sotheby's 34-35 New Bond Street Sporting Memorabilia London W1A 2AA United Kingdom Started 22 May 2014 10:00 BST

Graham Budd Auctions Sotheby's 34-35 New Bond Street Sporting Memorabilia London W1A 2AA United Kingdom Started 22 May 2014 10:00 BST Lot Description An 1896 Athens Olympic Games participation medal, in bronze, designed by N Lytras, struck by Honto-Poulus, the obverse with Nike 1 seated holding a laurel wreath over a phoenix emerging from the flames, the Acropolis beyond, the reverse with a Greek inscription within a wreath A Greek memorial medal to Charilaos Trikoupis dated 1896,in silver with portrait to obverse, with medal ribbonCharilaos Trikoupis was a 2 member of the Greek Government and prominent in a group of politicians who were resoundingly opposed to the revival of the Olympic Games in 1896. Instead of an a ...[more] 3 Spyridis (G.) La Panorama Illustre des Jeux Olympiques 1896,French language, published in Paris & Athens, paper wrappers, rare A rare gilt-bronze version of the 1900 Paris Olympic Games plaquette struck in conjunction with the Paris 1900 Exposition 4 Universelle,the obverse with a triumphant classical athlete, the reverse inscribed EDUCATION PHYSIQUE, OFFERT PAR LE MINISTRE, in original velvet lined red case, with identical ...[more] A 1904 St Louis Olympic Games athlete's participation medal,without any traces of loop at top edge, as presented to the athletes, by 5 Dieges & Clust, New York, the obverse with a naked athlete, the reverse with an eleven line legend, and the shields of St Louis, France & USA on a background of ivy l ...[more] A complete set of four participation medals for the 1908 London Olympic -

1985 NSCAA New Balance All-America Awards Banquet Cedarville College

Cedarville University DigitalCommons@Cedarville Men's Soccer Programs Men's Soccer Fall 1985 1985 NSCAA New Balance All-America Awards Banquet Cedarville College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.cedarville.edu/ mens_soccer_programs Part of the Higher Education Commons, and the Sports Studies Commons This Program is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@Cedarville, a service of the Centennial Library. It has been accepted for inclusion in Men's Soccer Programs by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Cedarville. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 1985 NSCAA/New Balance All-America Awards Banquet National Soccer Coaches Association of America Saturday, January 18, 1986 Sheraton - St. Louis Hotel St. Louis, Missouri Dear All-America Performer, Congratulations on being selected as a recipient of the National Soccer Coaches Association of America/New Balance All-America Award for 1985. Your selection as one of the top performers in the Gnited States is a tribute to your hard work, sportsmanship and dedication to the sport of soccer. All of us at New Balance are proud to be associated with the All-America Awards and look forward to presenting each of you with a separate award for your accomplishment. Good luck in your future endeavors and enjoy your stay in St. Louis. Sincerely, James S. Davis President new balance8 EXCLUSIVE SPONSOR OF THE NSCAA/NEW BALANCE ALL-AMERICA AWARDS Program NSCAA/New Balance All-America Awards Banquet Master of Cerem onies............................. William T. Holleman, Second Vice-President, NSCAA The Lovett School, Georgia Invocation.................................... ....................................................................... Whitney Burnham Dartmouth College NSCAA All-America Awards Youth Girl’s and Boy’s T ea m s............................................................................. -

Silva: Polished Diamond

CITY v BURNLEY | OFFICIAL MATCHDAY PROGRAMME | 02.01.2017 | £3.00 PROGRAMME | 02.01.2017 BURNLEY | OFFICIAL MATCHDAY SILVA: POLISHED DIAMOND 38008EYEU_UK_TA_MCFC MatDay_210x148w_Jan17_EN_P_Inc_#150.indd 1 21/12/16 8:03 pm CONTENTS 4 The Big Picture 52 Fans: Your Shout 6 Pep Guardiola 54 Fans: Supporters 8 David Silva Club 17 The Chaplain 56 Fans: Junior 19 In Memoriam Cityzens 22 Buzzword 58 Social Wrap 24 Sequences 62 Teams: EDS 28 Showcase 64 Teams: Under-18s 30 Access All Areas 68 Teams: Burnley 36 Short Stay: 74 Stats: Match Tommy Hutchison Details 40 Marc Riley 76 Stats: Roll Call 42 My Turf: 77 Stats: Table Fernando 78 Stats: Fixture List 44 Kevin Cummins 82 Teams: Squads 48 City in the and Offi cials Community Etihad Stadium, Etihad Campus, Manchester M11 3FF Telephone 0161 444 1894 | Website www.mancity.com | Facebook www.facebook.com/mcfcoffi cial | Twitter @mancity Chairman Khaldoon Al Mubarak | Chief Executive Offi cer Ferran Soriano | Board of Directors Martin Edelman, Alberto Galassi, John MacBeath, Mohamed Mazrouei, Simon Pearce | Honorary Presidents Eric Alexander, Sir Howard Bernstein, Tony Book, Raymond Donn, Ian Niven MBE, Tudor Thomas | Life President Bernard Halford Manager Pep Guardiola | Assistants Rodolfo Borrell, Manel Estiarte Club Ambassador | Mike Summerbee | Head of Football Administration Andrew Hardman Premier League/Football League (First Tier) Champions 1936/37, 1967/68, 2011/12, 2013/14 HONOURS Runners-up 1903/04, 1920/21, 1976/77, 2012/13, 2014/15 | Division One/Two (Second Tier) Champions 1898/99, 1902/03, 1909/10, 1927/28, 1946/47, 1965/66, 2001/02 Runners-up 1895/96, 1950/51, 1988/89, 1999/00 | Division Two (Third Tier) Play-Off Winners 1998/99 | European Cup-Winners’ Cup Winners 1970 | FA Cup Winners 1904, 1934, 1956, 1969, 2011 Runners-up 1926, 1933, 1955, 1981, 2013 | League Cup Winners 1970, 1976, 2014, 2016 Runners-up 1974 | FA Charity/Community Shield Winners 1937, 1968, 1972, 2012 | FA Youth Cup Winners 1986, 2008 3 THE BIG PICTURE Celebrating what proved to be the winning goal against Arsenal, scored by Raheem Sterling. -

Idub – the Potential of Intralingual Dubbing in Foreign Language Learning: How to Assess the Task

Language Value July 2017, Volume 9, Number 1 pp. 62-88 http://www.e-revistes.uji.es/languagevalue Copyright © 2017, ISSN 1989-7103 iDub – The potential of intralingual dubbing in foreign language learning: How to assess the task Noa Talaván [email protected] Tomás Costal [email protected] Universidad Nacional de Educación a Distancia, Spain ABSTRACT Research on the use of active dubbing activities in foreign language learning is gaining an increasing amount of attention. The most obvious skill to be enhanced in this context is oral production and a few authors have already mentioned the potential benefits of asking students to record their voices in a ‘semi- professional’ manner. The present project attempts to assess the potential of intralingual dubbing (English-English) to develop general oral production skills in adult university students of English B2 level in an online learning environment, and to provide general guidelines of dubbing task assessment for practitioners. To this end, a group of undergraduate pre-intermediate students worked on ten sequenced activities using short videos taken from an American sitcom over a period of two months. The research study included language assessment tests, questionnaires and observation as the basic data gathering tools to make the results as reliable and thorough as possible for this type of educational setting. The conclusions provide a good starting point for the establishment of basic guidelines that may help teachers implement dubbing tasks in the language class. Keywords: Audiovisual translation, dubbing, language learning, oral skills, online tasks, assessment rubric I. INTRODUCTION The iDub – Intralingual Dubbing to Improve Oral Skills project arose from the need to evaluate the potential didactic efficiency of dubbing as an active task in distance foreign language (henceforth, L2) environments as well as from the lack of assessment materials in this learning context. -

Football's Lost Decade

FOOTBALL’S Contrary to what Sky TV might have you believe, football did exist before 1992. In fact, the 1980s saw cultural and political change that shaped the modern game. But while LOST football wasn’t cool, some of us still loved it. Jon Howe looks back with nostalgia at the DECADE decade that football forgot... A game you might have forgotten Leeds United 1 Aston Villa 2 n August 16, 1980 The usual season-opening optimism was somewhat missing from Elland Road in August 1980. Despite the signing of Argentinean Alex Sabella for £400,000 from Sheffield United, Leeds fans were still smarting from a mediocre 11th-place finish the previous season, plus early and humiliating exits from both domestic cups and the UEFA Cup. It is safe to say that the words “Adamson out!” were not far from the vocal majority’s lips and they would be heard again before this afternoon was out. A Leeds fan in denial is a dangerous Alex Sabella in beast, and nobody liked to admit they action against were watching a club in transition, Aston Villa particularly when the direction of change was heading alarmingly the wrong way. That continued here, despite an explosive start when Brian Flynn earned a penalty in the opening exchanges, which was duly effort from Tony Morley. The England For Leeds it would be meagre fare for dispatched by Byron Stevenson after 177 winger was chief architect again on the much of another fruitless season. Jimmy seconds. In the searing heat Aston Villa hour when striker Gary Shaw bundled in Adamson was sacked and replaced by soon wrested control and with punishing the winner from close range. -

The British Academy Television Awards Sponsored by Pioneer

The British Academy Television Awards sponsored by Pioneer NOMINATIONS ANNOUNCED 11 APRIL 2007 ACTOR Programme Channel Jim Broadbent Longford Channel 4 Andy Serkis Longford Channel 4 Michael Sheen Kenneth Williams: Fantabulosa! BBC4 John Simm Life On Mars BBC1 ACTRESS Programme Channel Anne-Marie Duff The Virgin Queen BBC1 Samantha Morton Longford Channel 4 Ruth Wilson Jane Eyre BBC1 Victoria Wood Housewife 49 ITV1 ENTERTAINMENT PERFORMANCE Programme Channel Ant & Dec Saturday Night Takeaway ITV1 Stephen Fry QI BBC2 Paul Merton Have I Got News For You BBC1 Jonathan Ross Friday Night With Jonathan Ross BBC1 COMEDY PERFORMANCE Programme Channel Dawn French The Vicar of Dibley BBC1 Ricky Gervais Extra’s BBC2 Stephen Merchant Extra’s BBC2 Liz Smith The Royle Family: Queen of Sheba BBC1 SINGLE DRAMA Housewife 49 Victoria Wood, Piers Wenger, Gavin Millar, David Threlfall ITV1/ITV Productions/10.12.06 Kenneth Williams: Fantabulosa! Andy de Emmony, Ben Evans, Martyn Hesford BBC4/BBC Drama/13.03.06 Longford Peter Morgan, Tom Hooper, Helen Flint, Andy Harries C4/A Granada Production for C4 in assoc. with HBO/26.10.06 Road To Guantanamo Michael Winterbottom, Mat Whitecross C4/Revolution Films/09.03.06 DRAMA SERIES Life on Mars Production Team BBC1/Kudos Film & Television/09.01.06 Shameless Production Team C4/Company Pictures/01.01.06 Sugar Rush Production Team C4/Shine Productions/06.07.06 The Street Jimmy McGovern, Sita Williams, David Blair, Ken Horn BBC1/Granada Television Ltd/13.04.06 DRAMA SERIAL Low Winter Sun Greg Brenman, Adrian Shergold, -

Known Nursery Rhymes Residencies Fruit Eaten Remembered World

13 Nov. 1995 – Leah Betts in coma after taking ecstasy 26 Sep. 2007 – Myanmar government, using extreme force, cracks down on protests Blockbusters Bestall, A. – Rupert Annual 1982 Pratchett, T. – Soul Music Celery Hilden, Linda The Tortoise and the Eagle Beverly Hills Cop Goodfellas Speed Peanut Brittle Dial M for Murder Russ Abbott Arena Coast To Coast Gary Numan Live Rammstein Vast Ready to Rumble (Dreamcast) Known Nursery Rhymes 22 Nov. 1995 – Rosemary West sentenced to life imprisonment 06 Oct. 2007 – Musharraf breezes to easy re-election in Pakistan Buckaroo Bestall, A. – Rupert Annual 1984 Pratchett, T. - Sorcery Chard Hill, Debbie The Jackdaw and the Fox Beverly Hills Cop 2 The Goonies Speed 2 Pear Drops Dinnerladies The Ruth Rendell Mysteries Aretha Franklin Cochine Gene McDaniels The Living End Ramones Vegastones Resident Evil (Various) All Around the Mulberry Bush 14 Dec. 1995 – Bosnia peace accord 05 Nov. 2007 – Thousands of lawyers take to the streets to protest the state of emergency rule in Pakistan. Chess Bestall, A. – Rupert Annual 1985 Pratchett, T. – The Streets of Ankh-Morpork Chickpea Hiscock, Anna-Marie The Boy and the Wolf Bicentennial Man The Good, The Bad and the Ugly Spider Man Picnic Doctor Who The Saint Armand Van Helden Cockney Rebel Gene Pitney Lizzy Mercier Descloux Randy Crawford The Velvet Underground Robocop (Commodore 64) As I Was Going to St. Ives 02 Jan. 1996 – US Peacekeepers enter Bosnia 09 Nov. 2007 – Police barricade the city of Rawalpindi where opposition leader Benazir Bhutto plans a protest Chinese Checkers Bestall, A. – Rupert Annual 1988 Pratchett, T. -

The World Cup— a Pictorial History on Stamps by John F

Historic Events: The World Cup— A pictorial history on stamps by John F. Dunn With the World Cup beginning on June 12 and running through the championship game on July 13 in Brazil, we present here stamps that trace the history of this worldwide event from the first, 1930, competition to date. Prelude: The world’s most popular sport, football—known in the United States as soccer—has elements that trace back to ancient Greece and Rome, but the rules of the sport as we know it today came into fruition in the mid-19th Century in England, where various forms of the game were played as far back as the eight century. The first formal “International” competition was held in 1872, albeit it between England and Scotland. By 1900 the sport was sufficiently widespread that it was introduced as a demonstration sport (with no medals awarded), and then as a medal sport in the 1908 London Olympics. It was not until the 1920 Olympics that a non-Euro- pean nation competed—Egypt, along with 13 European teams—in a competition that was won by Belgium. Uru- guay won the 1924 and 1928 Olympics. By 1930, under the leadership of its President, Jules Rimet, the Federation Interna- tionale de Football Associations (FIFA) was ready to stage its own tournaments, free of the amateur restrictions of the Olympics. Hav- ing won the previous two Olympic Championships, and with the Jules Rimet and the first South American nation celebrates trophy, named “The God- its 100th Anniversary of inde- dess of Victory,” which pendence, Uruguay became the later came to be known as natural choice as the first World the Rimet Cup, on a stamp from Hungary. -

Arthur Mathews

Arthur Mathews Agent Katie Haines ([email protected]) In Development: PREPPERS (BBC Comedy) FLEMP (Roughcut Television) TOOTHTOWN with Simon Godley (Yellow Door Productions) Television: ROAD TO BREXIT (Objective/BBC Two) Starring Matt Berry TOAST OF LONDON (Objective/C4) Series 1, 2 & 3 Co-written with Matt Berry Nominated for BAFTA Best Situation Comedy 2014 Winner of the Rose d'Or for Best Sitcom at the 53rd Rose d'Or Festival 2014 Nominated for an RTS Programme Award 2013 TRACEY ULLMAN SHOW (BBC) 2015/16 Sketches FORKLIFTERS (Channel 4) VAL FALVEY (Grand Pictures / RTE1) Series 2 2010; Series 1 2008-9 6 x 30’ - co-written with Paul Woodfull Co-Director (Series 1) THIS IS IRELAND (CHX / BBC2) 2004 Writer and Script Editor BIG TRAIN (Talkback Productions / BBC2) Series 1 & 2 1998-2001 Co-Creator and Writer HIPPIES (Talkback Productions / BBC) 1999 Co-created and co-written with Graham Linehan FATHER TED (Hat Trick Productions / Channel 4) 3 Series 1995-1998 Co-created & Co-written with Graham Linehan HARRY & PAUL (Tiger Aspect Productions / BBC) SERIES C 2010 Various sketches THE EEJITS (Objective / Channel 4) 2007 Comedy Showcase Pilot MODERN MEN (TalkbackThames/Channel 4) 2007 Guest Writer / Script Editor for Armstrong & Bain IT CROWD (TalkbackThames/Channel 4) Series 2 2006 Writing Consultant STEW (Script Editor and Writer) 2003 -2006 Grand Pictures for RTE THE CATHERINE TATE SHOW (Tiger Aspect/BBC2) Series 1 & 2 2004/2005 Sketch Material BRASS EYE (TalkBack /Channel 4) 1997 Various Sketches THE FAST SHOW (BBC2) 1994-1997 -

Mbn Calendar

R A D S E P T E M B E R O C T O B E R D E C E M B E R D E C E M B E R N E PRIDE OF POST TOUR SPORTSMAN’S SOCCER SPEAKER COMEDY L ST GEORGE ROAR OF THE YEAR CHRISTMAS LUNCH Thursday 16th A Friday 10th Friday 8th Friday 10th The Brewery, The Brewery, Kimpton Clocktower, The Brewery, Manchester C Moorgate Moorgate Moorgate THE LONGEST A CELEBRATION OF A CONGREGATION A SELL OUT XMAS STANDING T EVERYTHING ENGLISH OF THE 1997 & 2021 LUNCH IN THE CITY CHRISTMAS EVENT IN SOUTH AFRICAN MANCHESTER With special guests: TOURING PARTIES N Previous guests include: With special guests: E Sir Ian With members of: Botham OBE Ricky Hatton Razor Ruddock V The 1997 & 2021 Martin Johnson CBE Eddie Jones Peter Reid & Paul Merson Touring Parties E & Harry Redknapp & Chris Sutton L U N C H L U N C H L U N C H L U N C H M B N P R O M O T I O N S . C O . U K E V E N T C A L E N D A R 2 0 2 1 A P R I L M A Y / J U N E O C T O B E R N O V E M B E R D E C E M B E R D E C E M B E R PRIDE OF AN EVENING RUGBY SPEAKER FOOTBALL’S SOCCER SPEAKER SPORTSMAN’S ST GEORGE WITH.. -

Basque Soccer Madness a Dissertation Submitted in Partial

University of Nevada, Reno Sport, Nation, Gender: Basque Soccer Madness A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Basque Studies (Anthropology) by Mariann Vaczi Dr. Joseba Zulaika/Dissertation Advisor May, 2013 Copyright by Mariann Vaczi All Rights Reserved THE GRADUATE SCHOOL We recommend that the dissertation prepared under our supervision by Mariann Vaczi entitled Sport, Nation, Gender: Basque Soccer Madness be accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Joseba Zulaika, Advisor Sandra Ott, Committee Member Pello Salaburu, Committee Member Robert Winzeler, Committee Member Eleanor Nevins, Graduate School Representative Marsha H. Read, Ph. D., Dean, Graduate School May, 2013 i Abstract A centenarian Basque soccer club, Athletic Club (Bilbao) is the ethnographic locus of this dissertation. From a center of the Industrial Revolution, a major European port of capitalism and the birthplace of Basque nationalism and political violence, Bilbao turned into a post-Fordist paradigm of globalization and gentrification. Beyond traditional axes of identification that create social divisions, what unites Basques in Bizkaia province is a soccer team with a philosophy unique in the world of professional sports: Athletic only recruits local Basque players. Playing local becomes an important source of subjectivization and collective identity in one of the best soccer leagues (Spanish) of the most globalized game of the world. This dissertation takes soccer for a cultural performance that reveals relevant anthropological and sociological information about Bilbao, the province of Bizkaia, and the Basques. Early in the twentieth century, soccer was established as the hegemonic sports culture in Spain and in the Basque Country; it has become a multi- billion business, and it serves as a powerful political apparatus and symbolic capital. -

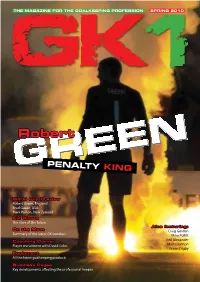

GK1 - FINAL (4).Indd 1 22/04/2010 20:16:02

THE MAGAZINE FOR THE GOALKEEPING PROFESSION SPRING 2010 Robert PENALTY KING World Cup Preview Robert Green, England Brad Guzan, USA Mark Paston, New Zealand Kid Gloves The stars of the future Also featuring: On the Move Craig Gordon Summary of the latest GK transfers Mike Pollitt Coaching Corner Neil Alexander Player recruitment with David Coles Matt Glennon Fraser Digby Equipment All the latest goalkeeping products Business Pages Key developments affecting the professional ‘keeper GK1 - FINAL (4).indd 1 22/04/2010 20:16:02 BPI_Ad_FullPageA4_v2 6/2/10 16:26 Page 1 Welcome to The magazine exclusively for the professional goalkeeping community. goalkeeper, with coaching features, With the greatest footballing show on Editor’s note equipment updates, legal and financial earth a matter of months away we speak issues affecting the professional player, a to Brad Guzan and Robert Green about the Andy Evans / Editor-in-Chief of GK1 and Director of World In Motion ltd summary of the key transfers and features potentially decisive art of saving penalties, stand out covering the uniqueness of the goalkeeper and hear the remarkable story of how one to a football team. We focus not only on the penalty save, by former Bradford City stopper from the crowd stars of today such as Robert Green and Mark Paston, secured the All Whites of New Craig Gordon, but look to the emerging Zealand a historic place in South Africa. talent (see ‘kid gloves’), the lower leagues is a magazine for the goalkeeping and equally to life once the gloves are hung profession. We actively encourage your up (featuring Fraser Digby).