Semitonal Succession-Classes in Prokofiev's Music and Their

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

On Modulation —

— On Modulation — Dean W. Billmeyer University of Minnesota American Guild of Organists National Convention June 25, 2008 Some Definitions • “…modulating [is] going smoothly from one key to another….”1 • “Modulation is the process by which a change of tonality is made in a smooth and convincing way.”2 • “In tonal music, a firmly established change of key, as opposed to a passing reference to another key, known as a ‘tonicization’. The scale or pitch collection and characteristic harmonic progressions of the new key must be present, and there will usually be at least one cadence to the new tonic.”3 Some Considerations • “Smoothness” is not necessarily a requirement for a successful modulation, as much tonal literature will illustrate. A “convincing way” is a better criterion to consider. • A clear establishment of the new key is important, and usually a duration to the modulation of some length is required for this. • Understanding a modulation depends on the aural perception of the listener; hence, some ambiguity is inherent in distinguishing among a mere tonicization, a “false” modulation, and a modulation. • A modulation to a “foreign” key may be easier to accomplish than one to a diatonically related key: the ear is forced to interpret a new key quickly when there is a large change in the number of accidentals (i.e., the set of pitch classes) in the keys used. 1 Max Miller, “A First Step in Keyboard Modulation”, The American Organist, October 1982. 2 Charles S. Brown, CAGO Study Guide, 1981. 3 Janna Saslaw: “Modulation”, Grove Music Online ed. L. Macy (Accessed 5 May 2008), http://www.grovemusic.com. -

Many of Us Are Familiar with Popular Major Chord Progressions Like I–IV–V–I

Many of us are familiar with popular major chord progressions like I–IV–V–I. Now it’s time to delve into the exciting world of minor chords. Minor scales give flavor and emotion to a song, adding a level of musical depth that can make a mediocre song moving and distinct from others. Because so many of our favorite songs are in major keys, those that are in minor keys1 can stand out, and some musical styles like rock or jazz thrive on complex minor scales and harmonic wizardry. Minor chord progressions generally contain richer harmonic possibilities than the typical major progressions. Minor key songs frequently modulate to major and back to minor. Sometimes the same chord can appear as major and minor in the very same song! But this heady harmonic mix is nothing to be afraid of. By the end of this article, you’ll not only understand how minor chords are made, but you’ll know some common minor chord progressions, how to write them, and how to use them in your own music. With enough listening practice, you’ll be able to recognize minor chord progressions in songs almost instantly! Table of Contents: 1. A Tale of Two Tonalities 2. Major or Minor? 3. Chords in Minor Scales 4. The Top 3 Chords in Minor Progressions 5. Exercises in Minor 6. Writing Your Own Minor Chord Progressions 7. Your Minor Journey 1 https://www.musical-u.com/learn/the-ultimate-guide-to-minor-keys A Tale of Two Tonalities Western music is dominated by two tonalities: major and minor. -

A. Types of Chords in Tonal Music

1 Kristen Masada and Razvan Bunescu: A Segmental CRF Model for Chord Recognition in Symbolic Music A. Types of Chords in Tonal Music minished triads most frequently contain a diminished A chord is a group of notes that form a cohesive har- seventh interval (9 half steps), producing a fully di- monic unit to the listener when sounding simulta- minished seventh chord, or a minor seventh interval, neously (Aldwell et al., 2011). We design our sys- creating a half-diminished seventh chord. tem to handle the following types of chords: triads, augmented 6th chords, suspended chords, and power A.2 Augmented 6th Chords chords. An augmented 6th chord is a type of chromatic chord defined by an augmented sixth interval between the A.1 Triads lowest and highest notes of the chord (Aldwell et al., A triad is the prototypical instance of a chord. It is 2011). The three most common types of augmented based on a root note, which forms the lowest note of a 6th chords are Italian, German, and French sixth chord in standard position. A third and a fifth are then chords, as shown in Figure 8 in the key of A minor. built on top of this root to create a three-note chord. In- In a minor scale, Italian sixth chords can be seen as verted triads also exist, where the third or fifth instead iv chords with a sharpened root, in the first inversion. appears as the lowest note. The chord labels used in Thus, they can be created by stacking the sixth, first, our system do not distinguish among inversions of the and sharpened fourth scale degrees. -

Sergei Prokofiev Russia Modern Era Composer (1891-1953)

Hey Kids, Meet Sergei Prokofiev Russia Modern Era Composer (1891-1953) Sergei Prokofiev was born in Russia on April 27, 1891. He began studying the piano with his mother at the age of three. By the age of five Sergei was displaying unusual musical abilities. His first composition, written down by his mother, was called Indian Gallop. By the age of nine he had written his first opera, The Giant. At the age of thirteen Sergei entered the St. Petersburg Conservatory having already produced a whole portfolio of compositions. While at the conservatory he studied with Russian composer Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov. Later in his life, Prokofiev was said to have regretted not having taken full advantage of this opportunity. The music that Prokofiev composed was new and different. He brought to the concert hall strange new harmonies, dynamic rhythms and lots of humor. When the Russian Revolution broke out, Prokofiev traveled to America. He hoped he would be able to compose in peace. American audiences, however, were not ready for his new sounds so he moved to Paris. In Paris, Prokofiev found greater success where his operas and ballets were well liked. Prokofiev returned to Russia in 1932 spending the last 19 years of his life in his home country. During this time, he produced some of his finest works including Peter and the Wolf for chamber orchestra and narrator, and the score for his ballet Romeo and Juliet which contained some of his most inspired music. Sergei Prokofiev died on March 5, 1953 as one of the most admired composers of the twentieth century. -

Comparison and Contrast of Performance Practice for the Tuba

COMPARISON AND CONTRAST OF PERFORMANCE PRACTICE OF THE TUBA IN IGOR STRAVINSKY’S THE RITE OF SPRING, DMITRI SHOSTAKOVICH’S SYMPHONY NO. 5 IN D MAJOR, OP. 47, AND SERGEI PROKOFIEV’S SYMPHONY NO. 5 IN B FLAT MAJOR, OP. 100 Roy L. Couch, B.M., M.M. Dissertation Prepared for the Degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS UNIVERSITY OF NORTH TEXAS May 2006 APPROVED: Donald C. Little, Major Professor Eugene Migliaro Corporon, Minor Professor Keith Johnson, Committee Member Brian Bowman, Coordinator of Brass Instrument Studies Graham Phipps, Program Coordinator of Graduate Studies in the College of Music James C. Scott, Dean of the College of Music Sandra L. Terrell, Dean of the Robert B. Toulouse School of Graduate Studies Couch, Roy L., Comparison and Contrast of Performance Practice for the Tuba in Igor Stravinsky’s The Rite of Spring, Dmitri Shostakovich’s Symphony No. 5 in D major, Op. 47, and Sergei Prokofiev’s Symphony No. 5 in B flat major, Op. 100, Doctor of Musical Arts (Performance), May 2006, 46 pp.,references, 63 titles. Performance practice is a term familiar to serious musicians. For the performer, this means assimilating and applying all the education and training that has been pursued in a course of study. Performance practice entails many aspects such as development of the craft of performing on the instrument, comprehensive knowledge of pertinent literature, score study and listening to recordings, study of instruments of the period, notation and articulation practices of the time, and issues of tempo and dynamics. The orchestral literature of Eastern Europe, especially Germany and Russia, from the mid-nineteenth century through the mid-twentieth century provides some of the most significant and musically challenging parts for the tuba. -

Chapter 21 on Modal Mixture

CHAPTER21 Modal Mixture Much music of the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries commonly employs a type of chromaticism that cannot be said to derive from applied functions and tonicization. In fact, the chromaticism often appears to be nonfunctional-a mere coloring of the melodic and harmonic surface of the music. Listen to the two phrases of Example 21.1. The first phrase (mm. 1-8) contains exclusively diatonic harmonies, but the second phrase (mm. 11-21) is full of chromaticism. This creates sonorities, such as the A~-major chord in m. 15, which appear to be distant from the underlying F-major tonic. The chromatic harmonies in mm. 11-20 have been labeled with letter names that indicate the root and quality of the chord. EXAMPLE 21.1 Mascagni, "A casa amici" ("Homeward, friends"), Cavalleria Rusticana, scene 9 418 CHAPTER 21 MODAL MIXTURE 419 These sonorities share an important feature: All but the cadential V-I are members of the parallel mode, F minor. Viewing this progression through the lens of F minor reveals a simple bass arpeggiation that briefly tonicizes 420 THE COMPLETE MUSICIAN III (A~), then moves to PD and D, followed by a final resolution to major tonic in the major mode. The Mascagni excerpt is quite remarkable in its tonal plan. Although it begins and ends in F major, a significant portion of the music behaves as though written in F minor. This technique of borrowing harmonies from the parallel mode is called modal mixture (sometimes known simply as mixture). We have already encountered two instances of modal mixture. -

Discover Seventh Chords

Seventh Chords Stack of Thirds - Begin with a major or natural minor scale (use raised leading tone for chords based on ^5 and ^7) - Build a four note stack of thirds on each note within the given key - Identify the characteristic intervals of each of the seventh chords w w w w w w w w % w w w w w w w Mw/M7 mw/m7 m/m7 M/M7 M/m7 m/m7 d/m7 w w w w w w % w w w w #w w #w mw/m7 d/wm7 Mw/M7 m/m7 M/m7 M/M7 d/d7 Seventh Chord Quality - Five common seventh chord types in diatonic music: * Major: Major Triad - Major 7th (M3 - m3 - M3) * Dominant: Major Triad - minor 7th (M3 - m3 - m3) * Minor: minor triad - minor 7th (m3 - M3 - m3) * Half-Diminished: diminished triad - minor 3rd (m3 - m3 - M3) * Diminished: diminished triad - diminished 7th (m3 - m3 - m3) - In the Major Scale (all major scales!) * Major 7th on scale degrees 1 & 4 * Minor 7th on scale degrees 2, 3, 6 * Dominant 7th on scale degree 5 * Half-Diminished 7th on scale degree 7 - In the Minor Scale (all minor scales!) with a raised leading tone for chords on ^5 and ^7 * Major 7th on scale degrees 3 & 6 * Minor 7th on scale degrees 1 & 4 * Dominant 7th on scale degree 5 * Half-Diminished 7th on scale degree 2 * Diminished 7th on scale degree 7 Using Roman Numerals for Triads - Roman Numeral labels allow us to identify any seventh chord within a given key. -

Viewed by Most to Be the Act of Composing Music As It Is Being

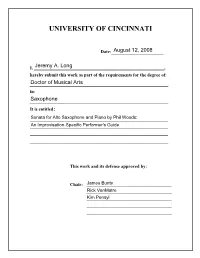

UNIVERSITY OF CINCINNATI Date:___________________ I, _________________________________________________________, hereby submit this work as part of the requirements for the degree of: in: It is entitled: This work and its defense approved by: Chair: _______________________________ _______________________________ _______________________________ _______________________________ _______________________________ Sonata for Alto Saxophone and Piano by Phil Woods: An Improvisation-Specific Performer’s Guide A doctoral document submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Cincinnati In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS In the Performance Studies Division of the College-Conservatory of Music By JEREMY LONG August, 2008 B.M., University of Kentucky, 1999 M.M., University of Cincinnati College-Conservatory of Music, 2002 Committee Chair: Mr. James Bunte Copyright © 2008 by Jeremy Long All rights reserved ABSTRACT Sonata for Alto Saxophone and Piano by Phil Woods combines Western classical and jazz traditions, including improvisation. A crossover work in this style creates unique challenges for the performer because it requires the person to have experience in both performance practices. The research on musical works in this style is limited. Furthermore, the research on the sections of improvisation found in this sonata is limited to general performance considerations. In my own study of this work, and due to the performance problems commonly associated with the improvisation sections, I found that there is a need for a more detailed analysis focusing on how to practice, develop, and perform the improvised solos in this sonata. This document, therefore, is a performer’s guide to the sections of improvisation found in the 1997 revised edition of Sonata for Alto Saxophone and Piano by Phil Woods. -

Music 160A Class Notes Dr. Rothfarb October 8, 2007 Key

Music 160A class notes Dr. Rothfarb October 8, 2007 Key determination: • Large-scale form in tonal music goes hand in hand with key organization. Your ability to recognize and describe formal structure will be largely dependent on your ability to recognize key areas and your knowledge of what to expect. Knowing what to expect: • Knowing what keys to expect in certain situations will be an invaluable tool in formal analysis. Certain keys are common and should be expected as typical destinations for modulation (we will use Roman numerals to indicate the relation to the home key). Here are the common structural key areas: o V o vi • Other keys are uncommon for modulation and are not structural: o ii o iii o IV Tonicization or modulation?: • The phenomena of tonicization and modulation provide a challenge to the music analyst. In both cases, one encounters pitches and harmonies that are foreign to the home key. How then, does one determine whether a particular passage is a tonicization or a modulation? • To begin with, this is a question of scale. Tonicizations are much shorter than modulations. A tonicization may last only one or two beats, while a modulation will last much longer—sometimes for entire sections. • A modulation will have cadences. These cadences confirm for the listener that the music has moved to a new key area. A tonicization—though it might have more than two chords—will not have cadences. • A modulation will also typically contain a new theme. Tonicizations, on the other hand, are finished too quickly to be given any significant thematic material. -

Tonical Ambiguity in Three Pieces by Sergei Prokofiev

TONICAL AMBIGUITY IN THREE PIECES BY SERGEI PROKOFIEV by DAVID VINCENT EDWIN STRATKAUSKAS B.Mus.,The University of British Columbia, 1992 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS in THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES (School of Music) We accept this thesis as conforming to the required standard THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA October 1996 © David Vincent Edwin Stratkauskas, 1996 In presenting this thesis in partial fulfilment of the requirements for an advanced degree at the University of British Columbia, I agree that the Library shall make it freely available for reference and study. I further agree that permission for extensive copying of this thesis for scholarly purposes may be granted by the head of my department or by his or her representatives. It is understood that copying or publication of this thesis for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. Department of MlASlC- The University of British Columbia Vancouver, Canada •ate OCTDKER II ; • DE-6 (2/88) ABSTRACT There is much that is traditional in the compositional style of Sergei Prokofiev, invoking the stylistic spirit of the preceding two hundred years. One familiar element is the harmonic vocabulary, as evidenced by the frequent use of simple triadic sonorities, but these seemingly simple sonorities are frequently instilled with a sense of multiple meaning, and help to facilitate a tonal style which differs from the classical norm. In this style, the conditions of monotonality do not necessarily apply; there is often a sense of the coexistence of several "tonical" possibilities. -

Major and Minor Scales Half and Whole Steps

Dr. Barbara Murphy University of Tennessee School of Music MAJOR AND MINOR SCALES HALF AND WHOLE STEPS: half-step - two keys (and therefore notes/pitches) that are adjacent on the piano keyboard whole-step - two keys (and therefore notes/pitches) that have another key in between chromatic half-step -- a half step written as two of the same note with different accidentals (e.g., F-F#) diatonic half-step -- a half step that uses two different note names (e.g., F#-G) chromatic half step diatonic half step SCALES: A scale is a stepwise arrangement of notes/pitches contained within an octave. Major and minor scales contain seven notes or scale degrees. A scale degree is designated by an Arabic numeral with a cap (^) which indicate the position of the note within the scale. Each scale degree has a name and solfege syllable: SCALE DEGREE NAME SOLFEGE 1 tonic do 2 supertonic re 3 mediant mi 4 subdominant fa 5 dominant sol 6 submediant la 7 leading tone ti MAJOR SCALES: A major scale is a scale that has half steps (H) between scale degrees 3-4 and 7-8 and whole steps between all other pairs of notes. 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 W W H W W W H TETRACHORDS: A tetrachord is a group of four notes in a scale. There are two tetrachords in the major scale, each with the same order half- and whole-steps (W-W-H). Therefore, a tetrachord consisting of W-W-H can be the top tetrachord or the bottom tetrachord of a major scale. -

Sergei Prokofiev-Romeo and Juliet Suite

Sergei Prokofiev (1891-1953) Romeo and Juliet Suite We are all not so distantly removed as to firmly recognize the tumultuous changes that shaped the world between 1891 and 1953. To imagine a composer’s life and work, within this period, without taking due notice of historical background is to ‘miss the boat’ entirely. If one could mention to what extent European composers from Ravel to Elgar were affected by World War I. If one could recognize the turmoil of World War II meted out upon music composition and performance in Europe. If one could add to this the emergence of the USSR on the one hand, and the climate of modernization on the other. This modernization in all matters would be no less prevalent in music and architecture. It would bring the Bauhaus school of Design and the sonically comparable Second Viennese School of Schoenberg, Webern and Berg to the fore, and deliver through the Darmstadt period the antecedence of our entire modern tableaux. One should also recognize how very quickly all this had happened, connecting in short shrift, the Victorian age emerging triumphalist from its industrial grime - to the second Elizabethan age of jet travel, the television and the Cold War. Prokofiev’s life, career and working style reflects his extraordinary presence in the global arena marked equally by his ‘on again-off again’ relationship with the authorities in the USSR. His early compositions, especially for piano are marked with an iconoclastic, willful, unconventional, revolution of their own. By 1908/9 Prokofiev had graduated in composition from the conservatory and by 1913/14 was the pride of the student body.