ACUNA Final Draft Dissertation-April 18 2016

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Volume 89 Number 1 March 2020 V Olume 89 Number 1 March 2020

Volume 89 Volume Number 1 March 2020 Volume 89 Number 1 March 2020 Historical Society of the Episcopal Church Benefactors ($500 or more) President Dr. F. W. Gerbracht, Jr. Wantagh, NY Robyn M. Neville, St. Mark’s School, Fort Lauderdale, Florida William H. Gleason Wheat Ridge, CO 1st Vice President The Rev. Dr. Thomas P. Mulvey, Jr. Hingham, MA J. Michael Utzinger, Hampden-Sydney College Mr. Matthew P. Payne Appleton, WI 2nd Vice President The Rev. Dr. Warren C. Platt New York, NY Robert W. Prichard, Virginia Theological Seminary The Rev. Dr. Robert W. Prichard Alexandria, VA Secretary Pamela Cochran, Loyola University Maryland The Rev. Dr. Gardiner H. Shattuck, Jr. Warwick, RI Treasurer Mrs. Susan L. Stonesifer Silver Spring, MD Bob Panfil, Diocese of Virginia Director of Operations Matthew P. Payne, Diocese of Fond du Lac Patrons ($250-$499) [email protected] Mr. Herschel “Vince” Anderson Tempe, AZ Anglican and Episcopal History The Rev. Cn. Robert G. Carroon, PhD Hartford, CT Dr. Mary S. Donovan Highlands Ranch, CO Editor-in-Chief The Rev. Cn. Nancy R. Holland San Diego, CA Edward L. Bond, Natchez, Mississippi The John F. Woolverton Editor of Anglican and Episcopal History Ms. Edna Johnston Richmond, VA [email protected] The Rev. Stephen A. Little Santa Rosa, CA Church Review Editor Richard Mahfood Bay Harbor, FL J. Barrington Bates, Prof. Frederick V. Mills, Sr. La Grange, GA Diocese of Newark [email protected] The Rev. Robert G. Trache Fort Lauderdale, FL Book Review Editor The Rev. Dr. Brian K. Wilbert Cleveland, OH Sheryl A. Kujawa-Holbrook, Claremont School of Theology [email protected] Anglican and Episcopal History (ISSN 0896-8039) is published quarterly (March, June, September, and Sustaining ($100-$499) December) by the Historical Society of the Episcopal Church, PO Box 1301, Appleton, WI 54912-1301 Christopher H. -

The Dancing God and the Mind of Zeus in Nonnos' Dionysiaca

Bard College Bard Digital Commons Senior Projects Spring 2017 Bard Undergraduate Senior Projects Spring 2017 Οὐδε γέρων Ἀστραῖος ἀναίνετο: The Dancing God and the Mind of Zeus in Nonnos’ Dionysiaca Doron Simcha Tauber Bard College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.bard.edu/senproj_s2017 Part of the Ancient History, Greek and Roman through Late Antiquity Commons, Classical Literature and Philology Commons, and the Indo-European Linguistics and Philology Commons This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 4.0 License. Recommended Citation Tauber, Doron Simcha, "Οὐδε γέρων Ἀστραῖος ἀναίνετο: The Dancing God and the Mind of Zeus in Nonnos’ Dionysiaca" (2017). Senior Projects Spring 2017. 130. https://digitalcommons.bard.edu/senproj_s2017/130 This Open Access work is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been provided to you by Bard College's Stevenson Library with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this work in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights- holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/or on the work itself. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Οὐδε γέρων Ἀστραῖος ἀναίνετο The Dancing God and the Mind of Zeus in Nonnos’ Dionysiaca Senior Project submitted to The Division of Languages and Literature of Bard College by Doron Simcha Tauber Annandale-on-Hudson, New York May 2017 For James, my Hymenaios Acknowledgements: Bill Mullen has been the captain of my errant ship, always strong on the rudder to keep my course on line. -

The Divine Alchemy of J. R. R. Tolkien's the Silmarillion David C

The Divine Alchemy of J. R. R. Tolkien’s The Silmarillion David C. Priester, Jr. Gray, GA B.A., English and Philosophy, Vanderbilt University, 2017 A Thesis presented to the Graduate Faculty of the University of Virginia in Candidacy for the Degree of Master of Arts Department of English University of Virginia May, 2020 Abstract J. R. R. Tolkien’s Silmarillion demonstrates a philosophy of creative imagination that is expressed in argumentative form in Tolkien’s essay “On Fairy Stories.” Fully appreciating the imaginative architecture of Tolkien’s fantastic cosmos requires considering his creative work in literary and theological dimensions simultaneously. Creative writing becomes a kind of spiritual activity through which the mind participates in a spiritual or theological order of reality. Through archetypal patterns Tolkien’s fantasy expresses particular ways of encountering divine presence in the world. The imagination serves as a faculty of spiritual perception. Tolkien’s creative ethic resonates with the theological aesthetics of Hans Urs von Balthasar, a consideration of which helps to illuminate the relationship of theology and imaginative literature in The Silmarillion. Creative endeavors may be seen as analogous to the works of alchemists pursuing the philosopher’s stone through the transfiguration of matter. The Silmarils symbolize the ideal fruits of creative activity and are analogous to the philosopher’s stone. Priester 1 The Divine Alchemy of J. R. R. Tolkien’s The Silmarillion Where shall we begin our study of J. R. R. Tolkien’s Silmarillion? The beginning seems like a very good place to start: “There was Eru, the One, who in Arda is called Ilúvatar; and he made first the Ainur, the Holy Ones, that were the offspring of his thought” (3). -

Memoirs of Hydrography

MEMOIRS 07 HYDROGRAPHY INCLUDING Brief Biographies of the Principal Officers who have Served in H.M. NAVAL SURVEYING SERVICE BETWEEN THE YEARS 1750 and 1885 COMPILED BY COMMANDER L. S. DAWSON, R.N. I 1s t tw o PARTS. P a r t II.—1830 t o 1885. EASTBOURNE: HENRY W. KEAY, THE “ IMPERIAL LIBRARY.” iI i / PREF A CE. N the compilation of Part II. of the Memoirs of Hydrography, the endeavour has been to give the services of the many excellent surveying I officers of the late Indian Navy, equal prominence with those of the Royal Navy. Except in the geographical abridgment, under the heading of “ Progress of Martne Surveys” attached to the Memoirs of the various Hydrographers, the personal services of officers still on the Active List, and employed in the surveying service of the Royal Navy, have not been alluded to ; thereby the lines of official etiquette will not have been over-stepped. L. S. D. January , 1885. CONTENTS OF PART II ♦ CHAPTER I. Beaufort, Progress 1829 to 1854, Fitzroy, Belcher, Graves, Raper, Blackwood, Barrai, Arlett, Frazer, Owen Stanley, J. L. Stokes, Sulivan, Berard, Collinson, Lloyd, Otter, Kellett, La Place, Schubert, Haines,' Nolloth, Brock, Spratt, C. G. Robinson, Sheringham, Williams, Becher, Bate, Church, Powell, E. J. Bedford, Elwon, Ethersey, Carless, G. A. Bedford, James Wood, Wolfe, Balleny, Wilkes, W. Allen, Maury, Miles, Mooney, R. B. Beechey, P. Shortland, Yule, Lord, Burdwood, Dayman, Drury, Barrow, Christopher, John Wood, Harding, Kortright, Johnson, Du Petit Thouars, Lawrance, Klint, W. Smyth, Dunsterville, Cox, F. W. L. Thomas, Biddlecombe, Gordon, Bird Allen, Curtis, Edye, F. -

Freedom from Violence and Lies Essays on Russian Poetry and Music by Simon Karlinsky

Freedom From Violence and lies essays on russian Poetry and music by simon Karlinsky simon Karlinsky, early 1970s Photograph by Joseph Zimbrolt Ars Rossica Series Editor — David M. Bethea (University of Wisconsin-Madison) Freedom From Violence and lies essays on russian Poetry and music by simon Karlinsky edited by robert P. Hughes, Thomas a. Koster, richard Taruskin Boston 2013 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data: A catalog record for this book as available from the Library of Congress. Copyright © 2013 Academic Studies Press All rights reserved ISBN 978-1-61811-158-6 On the cover: Heinrich Campendonk (1889–1957), Bayerische Landschaft mit Fuhrwerk (ca. 1918). Oil on panel. In Simon Karlinsky’s collection, 1946–2009. © 2012 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn Published by Academic Studies Press in 2013. 28 Montfern Avenue Brighton, MA 02135, USA [email protected] www.academicstudiespress.com Effective December 12th, 2017, this book will be subject to a CC-BY-NC license. To view a copy of this license, visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/. Other than as provided by these licenses, no part of this book may be reproduced, transmitted, or displayed by any electronic or mechanical means without permission from the publisher or as permitted by law. The open access publication of this volume is made possible by: This open access publication is part of a project supported by The Andrew W. Mellon Foundation Humanities Open Book initiative, which includes the open access release of several Academic Studies Press volumes. To view more titles available as free ebooks and to learn more about this project, please visit borderlinesfoundation.org/open. -

Visual Acuity Gain Profiles and Anatomical Prognosis Factors In

pharmaceutics Article Visual Acuity Gain Profiles and Anatomical Prognosis Factors in Patients with Drug-Naive Diabetic Macular Edema Treated with Dexamethasone Implant: The NAVEDEX Study Mauricio Pinto 1,†, Thibaud Mathis 1,2,†, Pascale Massin 3, Jad Akesbi 4, Théo Lereuil 1, Nicolas Voirin 5, Frédéric Matonti 6,7, Franck Fajnkuchen 8, John Conrath 7, Solange Milazzo 9, Jean-François Korobelnik 10,11 , Stéphanie Baillif 12, Philippe Denis 1, Catherine Creuzot-Garcher 13, Mayer Srour 14 ,Bénédicte Dupas 3 , Aditya Sudhalkar 15,16, Alper Bilgic 15 , Ramin Tadayoni 3, Eric H Souied 14, Corinne Dot 17,18 and Laurent Kodjikian 1,2,* 1 Department of Ophthalmology, Croix-Rousse University Hospital, 69004 Lyon, France; [email protected] (M.P.); [email protected] (T.M.); [email protected] (T.L.); [email protected] (P.D.) 2 UMR-CNRS 5510 Matéis, 69100 Villeurbane, France 3 Department of Ophthalmology, Lariboisière Hospital (AP-HP), University Paris 7 (Sorbonne Paris Cité), 75007 Paris, France; [email protected] (P.M.); [email protected] (B.D.); [email protected] (R.T.) 4 Quinze-Vingt National Eye Hospital, 75012 Paris, France; [email protected] 5 EPIMOD, Epidemiology and Modelling, 01240 Dompierre sur Veyle, France; [email protected] 6 Department of Ophthalmology, Marseille North Hospital, 13015 Marseille, France; [email protected] Citation: Pinto, M.; Mathis, T.; 7 Department of Ophthalmology, Monticelli’s Clinic, 13008 Marseille, France; [email protected] 8 Massin, P.; Akesbi, J.; Lereuil, T.; Department of Ophthalmology, Avicenne Hospital, 93022 Bobigny, France; [email protected] 9 Voirin, N.; Matonti, F.; Fajnkuchen, F.; Department of Ophthalmology, University Hospital of Amiens-Picardie, 80021 Amiens, France; [email protected] Conrath, J.; Milazzo, S.; et al. -

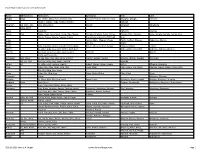

Given Name Alternatives for Irish Research Name Abreviations

Given Name Alternatives for Irish Research Name Abreviations Nicknames Synonyms Irish Latin Abigail Abig Ab, Abbie, Abby, Bina, Debbie, Gail, Abina, Deborah, Gobinet, Dora Abaigeal, Abaigh, Gobnata Gubbie, Gubby, Libby, Nabby, Webbie Gobnait Abraham Ab, Abm, Abr, Abe, Abby,Bram Abram Abraham Abrahame Abra, Abrm Adam Ade,Edie Adhamh Adamus Agnes Agn Aggie, Aggy, Ann,Annot, Assie, Inez, Nancy, Annais, Anneyce, Annis, Annys, Aigneis, Mor, Oonagh, Agna, Agneta, Agnetis, Agnus, Una Nanny, Nessa, Nessie, Taggett, Taggy Nancy,Una,Unity,Uny,Winifred Una Aidan Aedan,Edan, Mogue, Moses Aodh, Aodhan, Mogue Aedannus, Edanus Ailbhe Elli, Elly Ailbhe Aileen Allie, Eily,Ellie, Helen, Lena,Nel,Nellie,Nelly Eileen, Ellen, Eveleen, Evelyn Eibhilin, Eibhlin Helena Albert Al, Albie, Alby, Alvy, Bert, Bertie, Bird, Burt Ailbe, Ailbhe, Beirichtir Ailbertus, Alberti, Albertus Alberta Abertina, Albertine, Allie, Aubrey, Bert, Roberta Alberta Berta, Bertha, Bertie Alexander Aler, Alexr, Al, Ala, Alec, Ales, Alex, Alick, Allister, Alaster, Alistair, Sander Alasdair, Alastar, Alusdar, Alexander Alr, Alx, Alxr Andi, Ec, Ellick, Lex, Sandy, Xandra Saunder Alfred Alf Al, Alfie, Fred, Freddie, Freddy Albert, Alured, Alvery, Avery Ailfrid Alfredus, Aluredus Alice Ailse, Alcy, Alica, Alley, Allie, Ally, Alicia, Ellen Ailis, Aislinn, Alis, Eilish Alechea, Alecia, Alesia, Alicia, Alitia Eily, Elly, Elsie, Lisa, Lizzie Alicia Allie, Ally, Elsie, Lisa Alice, Alisha, Elisha Ailis, Ailise Alicia Allowshis Allow Aloyisius, Aloysius Aloysius Al, Alley, Allie, Ally, Lou, Louie -

I Llllll Lllll Lllll Lllll Lllll Lllll Lllll Lllll Llll Llll

Borrower: TXA Call#: QH75.A1 Internet Lending Strin{1: *COD,OKU,IWA,UND,CUI Location: Internet Access (Jan. 01, ~ 1997)- ~ Patron: Bandel, Micaela ;..... 0960-3115 -11) Journal Title: Biodiversity and conservation. ........'"O ;::::s Volume: 12 l~;sue: 3 0 ;;;;;;;;;;;;;;; ~ MonthNear: :W03Pages: 441~ c.oi ~ ;;;;;;;;;;;;;;; ~ 1rj - Article Author: 0 - ODYSSEY ENABLED '"O - crj = Article Title: DC Culver, MC Christman, WR ;..... - 0 Elliot, WR Hobbs et al.; The North American Charge ........ - Obligate Cave 1=auna; regional patterns 0 -;;;;;;;;;;;;;;; Maxcost: $501FM u -;;;;;;;;;;;;;;; <.,....; - Shipping Address: 0 - Imprint: London ; Chapman & Hall, c1992- Texas A&M University >-. ..... Sterling C. Evans Library, ILL ~ M r/'J N ILL Number: 85855887 5000 TAMUS ·-;..... N 11) LC) College Station, TX 77843-5000 ~ oq- Illllll lllll lllll lllll lllll lllll lllll lllll llll llll FEDEX/GWLA ·-~ z ~ I- Fax: 979-458-2032 "C cu Ariel: 128.194.84.50 :J ...J Email: [email protected] Odyssey Address: 165.91.74.104 B'odiversity and Conservation 12: 441-468, 2003. <£ 2003 Kluwer Academic Publishers. Printed in the Netherlands. The North American obligate cave fauna: regional patterns 1 2 3 DAVID C. CULVER ·*, MARY C. CHRISTMAN , WILLIAM R. ELLIOTT , HORTON H. HOBBS IIl4 and JAMES R. REDDELL5 1 Department of Biology, American University, 4400 Massachusetts Ave., NW, Washington, DC 20016, USA; 2 £epartment of Animal and Avian Sciences, University of Maryland, College Park, MD 20742, USA; 3M issouri Department of Conservation, Natural History Section, P.O. Box 180, Jefferson City, MO 65/02-0.'80, USA; 'Department of Biology, Wittenberg University, P.O. Box 720, Springfield, OH 45501-0:'20, USA; 5 Texas Memorial Museum, The University of Texas, 2400 Trinity, Austin, TX 78705, USA; *Author for correspondence (e-mail: [email protected]; fax: + 1-202-885-2182) Received 7 August 200 I; accepted in revised form 24 February 2002 Key wm ds: Caves, Rank order statistics, Species richness, Stygobites, Troglobites Abstrac1. -

Laguardia Community College/CUNY • Fall 2007 Publications: B Ooks

Faculty And Staff NTES LaGuardia Community College/CUNY • Fall 2007 Publications: b ooks, Barbara Comins’ “A Walk across the Bridge: articles and so ftwa re Transforming Space into Place” was published in The Association of Writers & Writing Programs Pedagogy Papers 2007. Abderrazak Belkharraz and Kenneth Timothy Coogan had his essay “The Lost Sobel published “Direct Adaptive Control for Air - Colony of Roanoke” published in Disasters, Acci - craft Control Surface Failures During Gust Condi - dents and Crises in American History , ed. Ballard tions,” accepted for publication in IEEE Transactions Campbell. New York: Facts On File, 2007. He had on Aerospace and Electronic Systems Journal. two essays, “Journeymen Carpenters Strike in Paul Arcario and Louis Lucca published Maxine Berger (ELA & CSE) and Martha New York (1833)” and “Sons of Liberty,” published “Online Advising through Virtual Interest Groups,” Siegel (ELA and ENG) have written a student in Encyclopedia of U.S. Labor and Working-Class in The Mentor: An Academic Advising Journal on workbook, New Land, New Language , (New Read - History , 3 vols., ed. Eric Arnesen. New York and October 9, 2006. ers Press, Syracuse, 2007). The book uses authen - London: Routledge, 2007. He also had his essay Paul Arcario’s article, “LaGuardia Receives tic (transcribed) immigrant voices as a common “Stepping Out: Student-Crafted Personalized Walk - FIPSE to SENCERize Math Instruction,” appeared unifying theme to teach communication skills. ing Tours of New York City,” accepted for publica - in the SENCER e-Newsletter , Volume 6, Issue 3, Nancy Berke selected and introduced the tion in the Fall, 2007 issue of In Transit: The November, 2006. -

The Wisdom of Noble Simplicity

The Εὐηθέστεροι Myth: the Wisdom of Noble Simplicity L. M. J. Coulson A Thesis Submitted in Fulfilment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Classics and Ancient History School of Philosophical and Historical Inquiry Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences The University of Sydney November 2016 Statement of Originality This is to certify that to the best of my knowledge, the content of this thesis is my own work. This thesis has not been submitted for any degree or other purposes. I certify that the intellectual content of this thesis is the product of my own work and that all the assistance received in preparing this thesis and sources have been acknowledged. L. M. J. Coulson November 2016 i Acknowledgements Throughout this undertaking it has been my great good fortune and privilege to have the gracious and generous support of my family, supervisors and colleagues. On November 5, 2012 Professor Eric Csapo and I met for the first time. At that meeting Eric suggested the apparently paradoxical use of εὐήθεια in Ancient Greece as a postgraduate research topic. This thesis is a direct consequence of his suggestion, encouragement and forbearance. Eric’s erudition in the Classics’ disciplines is extraordinary and gives constant cause for admiration. Professor Rick Benitez is officially designated as my auxiliary supervisor. However, he has been far more that that, especially in the last year of this project when the depth of his Platonic scholarship and generous support made an invaluable contribution to the completion of this thesis. I am grateful for the opportunity to have worked closely with these exceptional scholars. -

Cynthia's Revels

Cynthia's Revels Ben Johnson Cynthia's Revels Table of Contents Cynthia's Revels........................................................................................................................................................1 Ben Johnson...................................................................................................................................................1 INDUCTION.................................................................................................................................................2 PROLOGUE..................................................................................................................................................7 ACT I.............................................................................................................................................................8 ACT II..........................................................................................................................................................20 ACT III.........................................................................................................................................................31 ACT IV........................................................................................................................................................41 ACT V..........................................................................................................................................................64 i Cynthia's Revels Ben Johnson This page copyright -

Paired Progression and Regression in Award-Winning

Prizing Cycles of Marginalization: Paired Progression and Regression in Award-Winning LGBTQ-themed YA Fiction Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Christine N. Stamper Graduate Program in Education: Teaching and Learning The Ohio State University 2018 Dissertation Committee Mollie V. Blackburn, Advisor Michelle Ann Abate Linda T. Parsons 1 Copyrighted by Christine N. Stamper 2018 2 Abstract This dissertation is a text-based analysis of young adult novels that have won LGBTQ-focused awards, specifically the Stonewall Book Award and Lambda Literary Award. The project engages with queer theory (Puar; Duggan; Ferguson; Halberstam) and the frameworks of cultural capital and prizing canon formation (English; Kidd and Thomas; Kidd). Looking at the 61 YA novels that have been recognized by either Stonewall or Lambda between 2010 and 2017, I provide statistics about the identities, themes, and ideologies of and about LGBTQ people that are prominent within the awards’ canons. Pairing these statistics close readings of representative texts provides a rich analysis of the way these awards both subvert and uphold understandings of those minoritized for their gender or sexuality. Stonewall and Lambda aim to promote novels that provide diverse and inclusive LGBTQ representations. However, these representations construct understandings of LGBTQ identity that support hetero-, homo- and cisnormative constructions that are palatable to adult and heteronormative culture. Throughout, I refer to this often paradoxical balance as the pairing of progression and regression. I explore not only what is considered excellence but also how these texts construct a vision of LGBTQ lives that still fit within oppressive models of society.