Proceedings of the EBEEC 2014

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

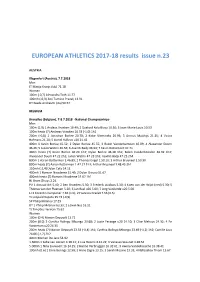

EUROPEAN ATHLETICS 2017-18 Results Issue N.23

EUROPEAN ATHLETICS 2017-18 results issue n.23 AUSTRIA Klagenfurt (Austria), 7.7.2018 Men JT Matija Kranjc (slo) 71.18 Women 100m (-0,7) Alexandra Toth 11.77 100mh (-0,3) Joni Tomicic Prezelj 13.91 DT Giada Andreutti (ita) 50.57 BELGIUM Bruxelles (Belgium), 7-8.7.2018 -National Champiosnhips- Men 100m (1.0) 1 Andeas Vranken 10.49; 2 Guelord Kola Biasu 10.50; 3 Jean-Marie Louis 10.53 100m heats (7) Andreas Vranken 10.53 (-1,0) 1h1 200m (-0,8) 1 Jonathan Borlee 20.78; 2 Kobe Vleminckx 20.96; 3 Arnout Matthijs 21.15; 4 Victor Hofmans 21.20; 5 Lionel Halleux u20 21.42 400m 1 Kevin Borlee 45.52; 2 Dylan Borlee 45.55; 3 Robin Vanderbemden 46.09, 4 Alexander Doom 46.46; 5 Julien Watrin 46.56; 6 Asamti Badji 46.94; 7 Kevin Dotremont 47.71 400m heats (7) Kevin Borlee 46.20 1h2; Dylan Borlee 46.28 1h1; Robin Vanderbemden 46.39 1h4; Alexander Doom 47.22 2h2; Julien Watrin 47.23 1h3; Asamti Badji 47.23 2h4 800m 1 Aaron Botterman 1.46.89; 2 Thomas Engel 1.50.10; 3 Arthur Bruyneel 1.50.30 800m heats (7) Aaron Botterman 1.47.27 1h1; Arthur Bruyneel 1.48.45 2h1 110mh (-2,4) Dylan Caty 14.11 400mh 1 Romain Nicodeme 51.49; 2 Dylan Owusu 51.67 400mh heats (7) Romain Nicodeme 51.62 1h1 HJ Bram Ghuys 2.24 PV 1 Arnaud Art 5.40; 2 Ben Broeders 5.30; 3 Frederik Ausloos 5.30; 4 Koen van der Wijst (ned) 5.30; 5 Thomas van der Plaetsen 5.20; 6 Jan Baal u20 5.00; 7 Jorg Vanlierde u20 5.00 LJ 1 Corentin Campener 7.66 (1.0); 2 Francois Grailet 7.56 (0.5) TJ Leopold Kapata 15.73 (-0,9) SP Philip Milanov 17.29 DT 1 Philip Milanov 63.39; 2 Edwin Nys 53.11 TJ Timothy Herman -

Download This PDF File

Research Journal of Finance and Accounting www.iiste.org ISSN 2222-1697 (Paper) ISSN 2222-2847 (Online) Vol.6, No.9, 2015 Investigating the Determinant of Return on Assets and Return on Equity and Its Industry Wise Effects in TSE (Tehran Security Exchange Market) Abolfazl Ghadiri Moghadam Mohammad Aranyan Morteza Eslami Mohammadiyeh Tayyebeh Rahati Farzaneh Nematizadeh Morteza Mehtar Islamic Azad University , Mashhad,Iran Abstract The purpose of this study is to find out that from the components of Dupont identity of Return on Equity which one is most consistent or volatile among profit margin, total assets turnover and equity multiplier in Fuel and Energy Sector, Chemicals Sector, Cement Sector, Engineering Sector, Textiles Sector and Transport and Communication Sector of TSE 100 index. The purpose of the study was served by taking data from 2004 to 2012 of 51 companies (falling under six mentioned industries) of TSE 100 as Paradigm of Panel Data. The F-Statistics of One Way ANOVA (Analysis of Variance) show that it is Assets Turnover which significantly varies from industry to industry whereas Equity Multiplier and Profit Margin are not much volatile among indifferent industries. Moreover, Adjusted R Square in Panel OLS Analysis has confirmed Industry Effect on Newly established firms from Fuel and Energy Sector, Cement Sector and Transport and Communication Sector whereas others Sectors such as Chemicals Sector, Engineering Sectors and Textiles Sectors does not have that leverage. Keywords: Profitability, Dupont Identity, Panel Least Square JEL Classification : G12, G39, C23 1. Introduction Business is Any activity which is done for the purpose of profit” but the question arises how to calculate profitability as well as comparing the profitability of it with existing firm of industry. -

Monaco 2017: Full Athletes' Bios (PDF)

Men's 100m Diamond Discipline 21.07.2017 Start list 100m Time: 21:35 Records Lane Athlete Nat NR PB SB 1 Omar MCLEOD JAM 9.58 9.99 WR 9.58 Usain BOLT JAM Berlin 16.08.09 2 Isiah YOUNG USA 9.69 9.97 9.97 AR 9.86 Francis OBIKWELU POR Athina 22.08.04 AR 9.86 Jimmy VICAUT FRA Paris 04.07.15 3 Chijindu UJAH GBR 9.87 9.96 9.98 AR 9.86 Jimmy VICAUT FRA Montreuil-sous-Bois 07.06.16 4 Usain BOLT JAM 9.58 9.58 10.03 NR 10.53 Sébastien GATTUSO MON Dijon 12.07.08 5 Akani SIMBINE RSA 9.89 9.89 9.92 WJR 9.97 Trayvon BROMELL USA Eugene 13.06.14 6 Christopher BELCHER USA 9.69 9.93 9.93 MR 9.78 Justin GATLIN USA 17.07.15 7 Yunier PÉREZ CUB 9.98 10.00 10.00 DLR 9.69 Yohan BLAKE JAM Lausanne 23.08.12 8 Bingtian SU CHN 9.99 9.99 10.09 SB 9.82 Christian COLEMAN USA Eugene 07.06.17 2017 World Outdoor list Medal Winners Road To The Final 9.82 +1.3 Christian COLEMAN USA Eugene 07.06.17 1 Andre DE GRASSE (CAN) 25 9.90 +0.9 Yohan BLAKE JAM Kingston 23.06.17 2016 - Rio de Janeiro Olympic Games 2 Ben Youssef MEITÉ (CIV) 24 9.92 +1.2 Akani SIMBINE RSA Pretoria 18.03.17 1. Usain BOLT (JAM) 9.81 3 Justin GATLIN (USA) 17 9.93 +0.8 Cameron BURRELL USA Eugene 07.06.17 2. -

CFA Institute Research Challenge Atlanta Society of Finance And

CFA Institute Research Challenge Hosted by Atlanta Society of Finance and Investment Professionals Team J Team J Industrials Sector, Airlines Industry This report is published for educational purposes only by New York Stock Exchange students competing in the CFA Research Challenge. Delta Air Lines Date: 12 January 2017 Closing Price: $50.88 USD Recommendation: HOLD Ticker: DAL Headquarters: Atlanta, GA Target Price: $57.05 USD Investment Thesis Recommendation: Hold We issue a “hold” recommendation for Delta Air Lines (DAL) with a price target of $57 based on our intrinsic share analysis. This is a 11% potential premium to the closing price on January 12, 2017. Strong Operating Leverage Over the past ten years, Delta has grown its top-line by 8.8% annually, while, more importantly, generating positive operating leverage of 60% per annum over the same period. Its recent growth and operational performance has boosted Delta’s investment attractiveness. Management’s commitment to invest 50% of operating cash flows back into the company positions Delta to continue to sustain profitable growth. Growth in Foreign Markets Delta has made an initiative to partner with strong regional airlines across the world to leverage its world-class service into new branding opportunities with less capital investment. Expansion via strategic partnerships is expected to carry higher margin growth opportunities. Figure 1: Valuation Summary Valuation The Discounted Cash Flows (DCF) and P/E analysis suggest a large range of potential share value estimates. Taking a weighted average between the two valuations, our bullish case of $63 suggests an attractive opportunity. However, this outcome presumes strong U.S. -

LIST Pole Vault Men - Final

REVISED Nairobi (KEN) 18-22 August 2021 START LIST Pole Vault Men - Final COMPETITION RESCHEDULED RECORDS RESULT NAME COUNTRY AGE VENUE DATE World U20 Record WU20R 6.05 Armand DUPLANTIS SWE 19 Olympiastadion, Berlin (GER) 12 Aug 2018 Championships Record CR 5.82 Armand DUPLANTIS SWE 19 Ratina Stadium, Tampere (FIN) 14 Jul 2018 World U20 Leading WU20L 5.72 Anthony AMMIRATI FRA 18 Chateau de l’Emperi, Salon-de-Provence ( 6 Jun 2021 20 August 2021 10:05 START TIME ORDER BIB NAME COUNTRY DATE of BIRTH PERSONAL SEASON BEST BEST 1 113 Aleksandr SOLOVYOV ANA 18 Feb 02 5.45i 5.45 i 2 275 Oihan ETCHEGARAY FRA 2 Dec 02 5.25 5.25 3 601 Oleksandr ONUFRIYEV UKR 15 Feb 02 5.44 5.44 4 307 Marcell NAGY HUN 22 Oct 02 5.22 5.22 5 140 Matvei VOLKOV BLR 13 Mar 04 5.60i 5.60 i 6 605 Nikita STROHALYEV UKR 1 Apr 02 5.15 5.15 7 335 Ameer Falih ABDULWAHID IRQ 1 Jan 02 5.20 5.20 8 266 Anthony AMMIRATI FRA 16 Jul 03 5.72 5.72 9 253 Juho ALASAARI FIN 29 Sep 03 5.42 5.42 10 577 Sedat CACIM TUR 10 Sep 02 5.21 5.21 11 524 Kyle RADEMEYER RSA 29 Jan 02 5.55 5.53 i 12 365 Matteo OLIVERI ITA 11 Nov 02 5.15 5.15 13 285 Sotirios CHYTAS GRE 17 May 02 5.21 5.10 HEIGHT PROGRESSION 4.85 5.05 5.20 5.30 5.35 5.40 i = Indoor performance ALL-TIME TOP LIST SEASON TOP LIST RESULT NAME VENUE DATE RESULT NAME VENUE 2021 6.05 Armand DUPLANTIS (SWE) Olympiastadion, Berlin (GER) 12 Aug 18 5.72 Anthony AMMIRATI (FRA)Chateau de l’Emperi, Salon-de-Provence ( 6 Jun 5.80 Maxim TARASOV (URS) Bryansk (URS) 14 Jul 89 5.50 Matvei VOLKOV (BLR) Bungertstadion, Rehlingen (GER) 23 May 5.80 Raphael HOLZDEPPE (GER) Biberach (GER) 28 Jun 08 5.44 Oleksandr ONUFRIYEV (UKR) Kadrioru staadion, Tallinn (EST) 18 Jul 5.75 Konstantinos FILIPPIDIS (GRE) Izmir (TUR) 18 Aug 05 5.43 Aleksandr SOLOVYOV (ANA) Sports Training Center, Ufa (RUS) 30 Jun 5.75 Christopher NILSEN (USA) Sacramento, CA (USA) 24 Jun 17 5.42 Juho ALASAARI (FIN) Kaarlen kenttä, Vaasa (FIN) 30 May 5.75 Sondre GUTTORMSEN (NOR)Olympiastadion, Berlin (GER) 12 Aug 18 5.40 Kyle RADEMEYER (RSA) Mike A. -

Provided by All-Athletics.Com Men's 100M Diamond Discipline 06.07.2017

Men's 100m Diamond Discipline 06.07.2017 Start list 100m Time: 21:20 Records Lane Athlete Nat NR PB SB 1 Kim COLLINS SKN 9.93 9.93 10.28 WR 9.58 Usain BOLT JAM Berlin 16.08.09 2 Henrico BRUINTJIES RSA 9.89 9.97 10.06 AR 9.86 Francis OBIKWELU POR Athina 22.08.04 AR 9.86 Jimmy VICAUT FRA Paris 04.07.15 3 Isiah YOUNG USA 9.69 9.97 9.97 AR 9.86 Jimmy VICAUT FRA Montreuil-sous-Bois 07.06.16 4 Akani SIMBINE RSA 9.89 9.89 9.92 NR 10.11 Alex WILSON SUI Weinheim 27.05.17 5 Justin GATLIN USA 9.69 9.74 9.95 WJR 9.97 Trayvon BROMELL USA Eugene 13.06.14 6 Ben Youssef MEITÉ CIV 9.96 9.96 9.99 MR 9.69 Yohan BLAKE JAM 23.08.12 7 Alex WILSON SUI 10.11 10.11 10.11 DLR 9.69 Yohan BLAKE JAM Lausanne 23.08.12 8 James DASAOLU GBR 9.87 9.91 10.11 SB 9.82 Christian COLEMAN USA Eugene 07.06.17 2017 World Outdoor list Medal Winners Road To The Final 9.82 +1.3 Christian COLEMAN USA Eugene 07.06.17 1 Andre DE GRASSE (CAN) 25 9.90 +0.9 Yohan BLAKE JAM Kingston 23.06.17 2016 - Rio de Janeiro Olympic Games 2 Ben Youssef MEITÉ (CIV) 17 9.92 +1.2 Akani SIMBINE RSA Pretoria 18.03.17 1. Usain BOLT (JAM) 9.81 3 Chijindu UJAH (GBR) 13 9.93 +1.8 Emmanuel MATADI LBR San Marcos 16.05.17 2. -

Men's Pole Vault International 02.09.2015

Men's Pole Vault International 02.09.2015 Start list Pole Vault Time: 18:00 Records Order Athlete Nat PB SB WR 6.16Renaud LAVILLENIE FRA Donetsk 15.02.14 1 Marquis RICHARDS SUI 5.55 5.30 AR 6.16Renaud LAVILLENIE FRA Donetsk 15.02.14 2 Mitch GREELEY USA 5.56 5.50 NR 5.71Felix BÖHNI SUI Bern 11.06.83 3 Carlo PAECH GER 5.80 5.80 WJR 5.80Maxim TARASOV URS Bryansk 14.07.89 4 Tobias SCHERBARTH GER 5.73 5.70 WJR 5.80 Raphael HOLZDEPPE GER Biberach 28.06.08 5 Konstantinos FILIPPIDIS GRE 5.91 5.91 MR 5.95Igor TRANDENKOV RUS 14.08.96 DLR 6.05Renaud LAVILLENIE FRA Eugene 30.05.15 6 Piotr LISEK POL 5.82 5.82 SB 6.05Renaud LAVILLENIE FRA Eugene 30.05.15 7 Paweł WOJCIECHOWSKI POL 5.91 5.84 8 Raphael HOLZDEPPE GER 5.94 5.94 2015 World Outdoor list 9 Shawn BARBER CAN 5.93 5.93 6.05Renaud LAVILLENIE FRA Eugene 30.05.15 5.94Raphael HOLZDEPPE GER Nürnberg 26.07.15 5.93Shawn BARBER CAN London 25.07.15 Medal Winners Zürich previous Winners 5.92Thiago BRAZ BRA Baku 24.06.15 2015 - Beijing IAAF World Ch. 12 Renaud LAVILLENIE (FRA) 5.70 5.91Konstantinos FILIPPIDIS GRE Paris 04.07.15 1. Shawn BARBER (CAN) 5.90 07 Igor PAVLOV (RUS) 5.75 5.84Paweł WOJCIECHOWSKI POL Lausanne 09.07.15 2. Raphael HOLZDEPPE (GER) 5.90 06 Brad WALKER (USA) 5.85 5.82Sam KENDRICKS USA Des Moines 25.04.15 3. -

Ratio Analysis Specifics of the Family Dairies' Financial

RATIO ANALYSIS SPECIFICS OF THE FAMILY DAIRIES’ FINANCIAL STATEMENTS Review article Economics of Agriculture 4/2015 UDC: 637.1:631.115.11:336.011 RATIO ANALYSIS SPECIFICS OF THE FAMILY DAIRIES’ FINANCIAL STATEMENTS Aleksandra Mitrović1, Snežana Knežević2, Milica Veličković3 Summary The subject of this paper is the evaluation of the financial analysis specifics of the dairy enterprises with a focus on the implementation of the ratio analysis of financial statements. The ratio analysis is a central part of financial analysis, since it is based on investigating the relationship between logically related items in the financial statements to assess the financial position of the observed enterprise and its earning capacity. Speaking about the reporting of financial performance in family dairies, the basis is created for displaying techniques of financial analysis, with a special indication on the specifics of their application in agricultural enterprises focusing on companies engaged in dairying. Applied in the paper is ratio analysis on the example of a dairy enterprise, i.e. a family dairy operating in Serbia. The ratio indicators are the basis for identifying relationships based on which by comparing the actual performance and certain business standards differences or variations are identified. Key words: financial analysis, financial ratio, family dairy, management, financial performance. JEL: M41, Q12 Introduction The challenges faced by agriculture - low selling price, rising production costs and other factors significantly affect revenues worldwide. The decline of traditional rural industrial branches, such as agriculture, mining and forestry in the past three decades have led the rural communities to explore and implement alternative ways of 1 Aleksandra Mitrović, M.Sc., Teaching Assistant, University of Kragujevac, Faculty of Hotel Management and Tourism, Vojvođanska street no. -

EUROPEAN ATHLETICS 2016-17 Results Issue N.30

EUROPEAN ATHLETICS 2016-17 results issue n.30 AUSTRIA Innsbruck (Austria), 26-27.8.2017 -National Championships in Combined Events- Men Decathlon u20 Florian Maier 6.833p (11.30 (0.0); 6.57 (0.29; 14.96; 1.85; 51.68 - 14.79 (-0,6); 35.96; 3.80; 44.19; 4.52.18) Women Heptathlon Sarah Lagger (99) 5.891p (14.39 (0.0); 1.78; 11.76; 24.97 (0.1) - 6.10 (0.0); 43.71; 2.17.31) BELGIUM Lanaken (Belgium), 25.8.2017 Women 800m Elise Van der Elst 2.09.92; 3.000m Louise Carton 9.11.48 CZECH REPUBLIC Jablonec nad Nisou (Czech Republic), 22.8.2017 Men PV Dan Barta (98) 5.00 Women 200m (0.6) Anna Pakys (pol) 24.58 Kolin (Czech Republic), 23.8.2017 Men 60m (0.0) 1 Jan Veleba 6.77; 2 Stepan Hampl (99) 6.80; 100m (0.0) 1 Jan Veleba 10.54; 2 Stepan Hampl (99) 10.64; 200m (0.1) 1 Jan Veleba 21.28; 2 Michal Tlusty 21.47; 3 Stepan Hampl (99) 21.67; HJ 1 Jaroslav Baba 2.14; 2 Matyas Dalecky 2.14 Women 60m (-0,1) Helena Jiranová 7.46; 100m (0.0) Helena Jiranová 11.74; 200m (0.9) Helena Jiranová 23.98; 1.000m 1 Diana Mezulianiková 2.46.67; 2 Monika Hrachovcová 2.53.09; HT Katerina Safranková 67.68 Olomouc (Czech Republic), 23.8.2017 Men SP u18 (5 kg) Jakub Heza 18.49 Women 150m (1.8) 1 Lucie Domská 18.10; 2 Alena Symerska 18.18; 300m Alena Symerska 39.22 DENMARK Kobenhavn (Denmark) 19-20.8.2017 -National Championships in Combined Events- Men 150m (0.6) 1 Frederik Schou 15.95; 2 Pau Fradera (esp) 16.20; 400m 1 Marquis Caldwell 48.36; 2 Pau Fradera (esp) 48.71; 110mh (0.0) 1 Alexander Brorsson (swe) 14.18; 2 Anton Levin (swe) 14.26; DT Emil Mikkelsen 52.71; Decathlon Christian L. -

RESULTS Pole Vault Men - Qualification with Qualifying Standard of 5.75 (Q) Or at Least the 12 Best Performers (Q) Advance to the Final

Doha (QAT) 27 September - 6 October 2019 RESULTS Pole Vault Men - Qualification With qualifying standard of 5.75 (Q) or at least the 12 best performers (q) advance to the Final RECORDS RESULT NAME COUNTRY AGE VENUE DATE World Record WR 6.16 Renaud LAVILLENIE FRA 28 Donetsk (Sport Palace Druzhba) 15 Feb 2014 Championships Record CR 6.05 Dmitri MARKOV AUS 26 Edmonton (Commonwealth Stadium) 9 Aug 2001 World Leading WL 6.06 Sam KENDRICKS USA 27 Des Moines, IA (USA) 27 Jul 2019 Area Record AR National Record NR Personal Best PB Season Best SB 28 September 2019 17:29 START TIME 25° C 67 % Group A TEMPERATURE HUMIDITY 19:50 END TIME 25° C 67 % 5.30 5.45 5.60 5.70 5.75 PLACE NAME COUNTRY DATE of BIRTH ORDER RESULT 1 Sam KENDRICKS USA 7 Sep 92 8 5.75 Q O O O O O 2 Thiago BRAZ BRA 16 Dec 93 5 5.75 Q - O O O XO 3 Claudio Michel STECCHI ITA 23 Nov 91 2 5.75 Q - - O XO XO 4 Bokai HUANG CHN 26 Sep 96 7 5.75 Q PB - O XXO XO XO 5 Valentin LAVILLENIE FRA 16 Jul 91 12 5.70 q - O O O XXX 6 Ben BROEDERS BEL 21 Jun 95 14 5.70 q - XO XO O XXX 7 Paweł WOJCIECHOWSKI POL 6 Jun 89 9 5.70 - O O XXO XXX 8 Emmanouil KARALIS GRE 20 Oct 99 1 5.60 - O O XXX 9 Bangchao DING CHN 11 Oct 96 16 5.60 XO XO XXO XXX 10 Zachery BRADFORD USA 29 Nov 99 10 5.60 XXO XO XXO XXX 11 Torben BLECH GER 12 Feb 95 11 5.45 O O XX- r 12 Minsub JIN KOR 2 Sep 92 15 5.45 - XO - XXX 13 Daichi SAWANO JPN 16 Sep 80 3 5.45 - XXO XXX 14 Masaki EJIMA JPN 6 Mar 99 13 5.45 XO XXO XXX Melker SVÄRD JACOBSSON SWE 8 Jan 94 4 DNS Menno VLOON NED 11 May 94 6 DNS 1 Timing by SEIKO AT-PV-M-q----.RS6..v1 Issued -

To Study the Relationship Between Return on Equity and the Intrinsic Value of the Stock in Basic Metals Industry Companies Listed in Tehran Stock Exchange (TSE)

Special Issue INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF HUMANITIES AND January 2016 CULTURAL STUDIES ISSN 2356-5926 To Study the Relationship between Return on Equity and the Intrinsic Value of the Stock in Basic Metals Industry Companies Listed in Tehran Stock Exchange (TSE) Mahdi Mahdian Rizi Department of Financial Management, Science and Research Branch, Islamic Azad University, Iran Sayyid Hossin Miri Department of Financial Management, Science and Research Branch, Islamic Azad University, Iran Abstract This is a continuous operation in the capital market using tools such as financial ratios and charts to measure the value of a stock and select the appropriate stock between stakeholders and financial decision makers. More common is the use of charts in the technical analysts and common between fundamental analysts using ratios and predictions. Financial decision makers and investors are seeking to find the best performance metrics, this issue has led the financial researchers’ part of Research and Development Programs spend for choice Best performance metrics. This paper examines the relationship between DuPont ratio that calculates the return on equity by the financial statements information and it is an accounting ratio with the expected value of the stock that calculate the intrinsic value of stocks by using economic data. For above studies selected companies active in Basic metals industries Tehran Stock Exchange during the five year period from 1386 to the end of 1390. The article used the Pearson correlation coefficient, to test the hypothesis and significant relationship between the variables. The result of this study suggests that, there is a significant relationship between the intrinsic value of stock and equity returns. -

Financial Statement Analysis 71 Financial Statement 4 Analysis LEARNING OUTCOMES

CHAPTER Financial Statement Analysis 71 Financial Statement 4 Analysis LEARNING OUTCOMES After reading this chapter, you will be able to: l Understand the utility and nature of financial statement analysis l Comprehend and interpret horizontal and vertical analysis l Assess profitability through computation and interpretation of ratios l Use ratio analysis for assessing liquidity of a firm l Use ratio analysis for assessing solvency l Understand the computation and interpretation of DuPont ratio OPENING EXHIBIT: EXCERPTS FROM ANNUAL REPORT (2014–2015) OF TITAN COMPANY LTD Directors’ Report was achieved through meticulous planning and execution The economic outlook for the year 2014–2015 was prom- of key initiatives. The income from the jewellery segment ising while improvement in consumer demand was quite grew by 9.24%, touching INR 9,429.97 crore. The income lukewarm. The company’s jewellery business was also from other segments comprising Precision Engineering, a impacted due to regulatory changes and termination of B2B Business, the Eyewear Business, and accessories the consumer-friendly Golden Harvest Scheme. The com- grew by 12.91% to INR 564.31 crore. The year witnessed pany’s brands witnessed good growth during the first half aggressive expansion of the company’s retail network with while in the later half, they witnessed a decline due to the a net addition of 123 stores. As on 31 March 2015, the absence of the Golden Harvest Scheme, which used to company had 1201 stores, with over 1.59 million sq. ft of contribute about 30% of the Jewellery Division’s revenues. retail space delivering a retail turnover of just under INR The company will however continue to invest in strategic 12,000 crore.