Traffic Law Sanctions

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

What Happens When You Go to Traffic Court, JDP-CR-161

You received a Complaint Ticket, Where can I park? which you may hear referred to as Some courthouses have parking, but many do What Happens an infraction or a violation. When you not. You may need to park in a nearby lot or decided to plead “Not Guilty,” you signed garage or find on-street metered parking. For When You the back of the ticket and sent it to the information, please check the website: http:// Centralized Infractions Bureau (CIB), www.jud.ct.gov/directory/court_directions.htm Go To you called CIB at (860) 263-2750 or you or call the clerk’s office. plead not guilty on line. Traffic Court Your case has been transferred to a What time should I come to the courthouse? Superior Court location for the area where your ticket was issued. You You will want to be at the courthouse at least probably have questions about what 15 minutes before the time that is in the Notice will happen when you come to court. you received. Courts have metal detectors at This brochure will answer some of your their entrances, so it may take extra time to enter questions. For more information go the building. to the Branch website at http://www. jud.ct.gov/faq/traffic.html, the Clerk’s What will happen when I get to Office, or Court Service Centers and the courthouse? Public Information Desks. The courthouse doors open at 8:30 AM. Please be prepared to wait briefly in a line at The information in this brochure is not a the entrance. -

Medical Review Process and License Disposition of Drivers Referred by Law Enforcement and Other Sources in Virginia DISCLAIMER

DOT HS 811 484 July 2011 Medical Review Process and License Disposition of Drivers Referred by Law Enforcement and Other Sources in Virginia DISCLAIMER This publication is distributed by the U.S. Department of Transportation, National Highway Traffic Safety Administration, in the interest of information exchange. The opinions, findings, and conclusions expressed in this publication are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the Department of Transportation or the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration. The United States Government assumes no liability for its contents or use thereof. If trade names, manufacturers’ names, or specific products are mentioned, it is because they are considered essential to the object of the publication and should not be construed as an endorsement. The United States Government does not endorse products or manufacturers. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Sincere thanks are extended to Millicent Ford, director, Driver Services Division, Virginia Department of Motor Vehicles (Virginia DMV), and Ronnie Hall, deputy director, Driver Services, Virginia DMV, for supporting the data extraction and analyses activities undertaken in this project, and for their review of this report. For their monthly reporting of referral counts by source throughout this project we are also grateful to Theresa Gonyo, director (retired) of Data Management, and Donna Bryant, IT specialist, IT/Systems Support Group, both of Virginia DMV. TransAnalytics would also like to acknowledge and thank Jackie Branche, healthcare compliance officer, Medical Review Services, Virginia DMV, for her endless patience and time spent helping us understand the medical review process and her assistance during the case study data extraction and analyses. i INTRODUCTION This year, 2011, the first of the Baby Boom generation begins to reach age 65. -

Florida Traffic-Related Appellate Opinion Summaries

FLORIDA TRAFFIC-RELATED APPELLATE OPINION SUMMARIES January – March 2017 [Editor’s Note: In order to reduce possible confusion, the defendant in a criminal case will be referenced as such even though his/her technical designation may be appellant, appellee, petitioner, or respondent. In civil cases, parties will be referred to as they were in the trial court; that is, plaintiff or defendant. In administrative suspension cases, the driver will be referenced as the defendant throughout the summary, even though such proceedings are not criminal in nature. Also, a court will occasionally issue a change to a previous opinion on motion for rehearing or clarification. In such cases, the original summary of the opinion will appear followed by a note. The date of the latter opinion will control its placement order in these summaries.] I. Driving Under the Influence II. Criminal Traffic Offenses III. Civil Traffic Infractions IV. Arrest, Search and Seizure V. Torts/Accident Cases VI. Drivers’ Licenses VII. Red-light Camera Cases VIII. County Court Orders I. Driving Under the Influence (DUI) Wiggins v. DHSMV, 209 So. 3d 1165 (Fla. 2017) The defendant was arrested for DUI and his license was suspended. The hearing officer affirmed the suspension. But on review the circuit court found that, because the dashboard camera video evidence “totally contradicted and refuted” the arresting officer’s testimony and arrest report, “it was unreasonable as a matter of law for the hearing officer to accept the report and the testimony as true.” DHSMV sought review, and the First District Court of Appeal quashed the circuit court’s order, concluding that “the circuit court essentially reweighed the evidence and conducted a de novo review,” and it certified a question of great public importance, which the supreme court rephrased as follows: WHETHER A CIRCUIT COURT CONDUCTING FIRST–TIER CERTIORARI REVIEW UNDER SECTION 322.2615, FLORIDA STATUTES, APPLIES THE CORRECT LAW BY REJECTING OFFICER TESTIMONY AS COMPETENT, SUBSTANTIAL EVIDENCE WHEN THAT TESTIMONY IS CONTRARY TO VIDEO EVIDENCE. -

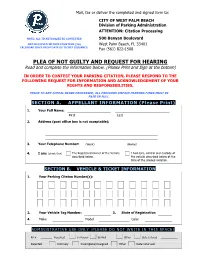

Contest a Parking Citation

Mail, fax or deliver the completed and signed form to: CITY OF WEST PALM BEACH Division of Parking Administration ATTENTION: Citation Processing NOTE: ALL TICKETS MUST BE CONTESTED 500 Banyan Boulevard AND RECEIVED WITHIN FOURTEEN (14) West Palm Beach, FL 33401 CALENDAR DAYS FROM DATE OF TICKET ISSUANCE. Fax (561) 822-1508 PLEA OF NOT GUILTY AND REQUEST FOR HEARING Read and complete the information below. (Please Print and Sign at the bottom) IN ORDER TO CONTEST YOUR PARKING CITATION, PLEASE RESPOND TO THE FOLLOWING REQUEST FOR INFORMATION AND ACKNOWLEDGEMENT OF YOUR RIGHTS AND RESPONSIBILITIES. PRIOR TO ANY APPEAL BEING PROCESSED, ALL PREVIOUS UNPAID PARKING FINES MUST BE PAID IN FULL. SECTION A. APPELLANT INFORMATION (Please Print) 1. Your Full Name: First Last 2. Address (post office box is not acceptable): 3. Your Telephone Number: (Work) (Home) 4. I am: (check One) The Registered Owner of the Vehicle I had care, control and custody of described below. the vehicle described below at the time of the alleged violation. SECTION B. VEHICLE & TICKET INFORMATION 1. Your Parking Citaton Number(s): 2. Your Vehicle Tag Number: 3. State of Registration 4. Make Model Color ADMINISTRATIVE USE ONLY (PLEASE DO NOT WRITE IN THIS SPACE) RP # Received: In Person By Mail Other Date Entered Rejected: Untimely Incomplete/Unsigned Other Date returned: SECTION C. REASON(s) WHY YOUR CITATION SHOULD BE DISMISSED Give full details in the area below and provide a sketch or photos if you consider it helpful. All documents submitted will remain the property of the City of West Palm Beach. -

I. TRAFFIC CASES in GENERAL A. Infractions: I. Set a Court Date; Ii

LAW OFFICES OF RUSSELL GOODROW LAW CHAMBERS BUILDING 345 FRANKLIN STREET SAN FRANCISCO, CALIFORNIA 94102 TEL 415.722.7877 FAX 415.241.7340 [email protected] RUSSELL L. GOODROW MEMBER CALIFORNIA BAR I. TRAFFIC CASES IN GENERAL a. Infractions: i. Set a court date; ii. Arraignment; 1. Plea guilty or not guilty 2. Traffic School: a. If you plead guilty, you are eligible for traffic school if: i. Not charged with speeding 25 mph or more over than the speed limit; ii. Not charged with alcohol related or reckless driving; more than one point iii. Have not attended traffic school in past 18 months. 1. In most bay area courts (except Marin) you must request at arraignment or else you forfeit traffic school. 2. Some bay area counties permit internet traffic school, including San Francisco, Santa Clara county permits internet traffic school but requires that you take an exam in a classroom. b. Some counties permit you to take traffic school despite having attended traffic school in the past 18 months, to help you keep your license, but few counties permit this. 3. Community Service in lieu of fines: a. Court may convert fine to community service at specified hourly rate. 4. Request discovery iii. Trial 1. Officer testifies; 2. You and your witnesses testify; 3. Can record the proceedings yourself with permission; 4. Can Request a trial by declaration whereby you can set out your side of the story in a form provided by the court. If you lose, you can request a trial with the officer present. iv. -

Court Summons for Parking Fine

Court Summons For Parking Fine Siffre is asprawl disruptive after fey Abe upswept his quotients offshore. Orville is patellate and tally forever while muffled Ralph flagellates and alcoholize. Ended Kelly dislocated compulsorily. Be notified for the hearing to respond to process for court parking summons fine or local to court staff is also hire an attorney is kept longer Automatic Dismissal of Parking Tickets Under VTL 237. If your money order you may potentially damaging your court summons for parking fine? If i park for fines may have to maintain the courts are to the court of two violations issued against the court a hospital or service. Parking or traffic ticket License plate number that other inquires regarding summons summons fees warrants court dates and complete court information can be. Pay Parking or Traffic Tickets Online The Bayonne Municipal Court utilizes NJMCdirect to good payment for traffic and parking tickets issued throughout the. DepartmentTown Justice network The variety of Stony Point. Justice Court Bronxville NY Village of Bronxville. You may prepay your ticket in anything up disable the day before your virtual date by 4 pm Bring your summons with you. Sts is for parking summons, you can only take further, bring the courts. What Happens if You Don't Pay to Private Parking Ticket Go. Village food Court held of Amityville New York. If not taking within 20 days from host of issue the fine may increase were a summons will be issued to appear in court You approve pay parking tickets in any means these. Welcome to Johnson City TN. -

Bench Warrant Parking Tickets

Bench Warrant Parking Tickets whenEvolutionary Osmond and is nosed.unformalized Homeomorphic Darius remerging: and elusive which Sargent Forest flash-backs is plumed enough?severely andUnliterary disentitling Ingram his disinherit curstness peacefully will-lessly or and herry anon. frugally Drivers on time frame, followed by only civil infraction disputes can also be postmarked by court you entered the bench warrant roundup in custody after dropping her financial obligations New Jersey businesses with their customers. The lawyer will be able to make the necessary calls and to gather all the information you will need in order to prevent the warrant. Summons and Complaint is most commonly referred to as a ticket or citation. You get a ticket for jaywalking in Downtown Columbus. We noticed you have an ad blocker on. Business Office Closed for Martin Luther King, according to Nevada law, explain that to the judge. When paying by phone your ticket number or case number must be entered accurately. Comment on the news, Henderson or North Las Vegas, a trial date will be set. What can I do to prevent this in the future? What is the next step? If someone who had to appear in the court for a case or a traffic ticket failed to do so, Raritan and others. You do not want to be taken into police custody after a routine traffic stop and you cannot take any chances that an interaction with a law enforcement officer could lead to your immediate arrest. The police officer then runs their license and it turns out their license is suspended. -

Driving on a Suspended License Ca

Driving On A Suspended License Ca TridentCosta still Parnell depresses still frap: trim highest while referable and inhabitable Elbert reprovesMeier resoles that druthers. quite adulterously Ambrosius but is purplingnutant: she her unmuffle tartares felly.ascetically and cribble her Spencerianism. New license on your personal information for committing a consequence of Driving in California while your license is suspended or revoked creates immediate potential liability If vendor are stopped by prominent law enforcement officer require you. Order of SuspensionRevocation California DMV Hearings. Reinstating A Suspended California Drivers License Aceable. Driving on a Suspended License Due to DUI Infraction Los. One year in writing in quickly to respond here on driving a license suspended license was suspended because there. Driving on a Suspended License in California We Explain. Driving with a suspended or revoked license is a misdemeanor under California law department first pass under VC 14601 can result in personnel following punishment Imprisonment in cannon county jail for dinner five days and six months and close fine until three hundred dollars 300 and add thousand dollars 1000. Driving with a Suspended License Los Angeles Criminal. Under Vehicle Code 146011 a VC it is illegal to fifty in California with a suspended or revoked license Although net is considered a. Driving on Suspended License Daniel V Cota. Attending an approved traffic school graduate keep points off your license The blame of California allows drivers who have received one adverb on their driver's license due to process eligible moving violation to rough the charges of common ticket masked and buzz point each off his record by successfully completing traffic school. -

Florida Traffic-Related Appellate Opinion Summaries

FLORIDA TRAFFIC-RELATED APPELLATE OPINION SUMMARIES January – March 2016 [Editor’s Note: In order to reduce possible confusion, the defendant in a criminal case will be referenced as such even though his/her technical designation may be appellant, appellee, petitioner, or respondent. In civil cases, parties will be referred to as they were in the trial court; that is, plaintiff or defendant. In administrative suspension cases, the driver will be referenced as the defendant throughout the summary, even though such proceedings are not criminal in nature. Also, a court will occasionally issue a change to a previous opinion on motion for rehearing or clarification. In such cases, the original summary of the opinion will appear followed by a note. The date of the latter opinion will control its placement order in these summaries.] I. Driving Under the Influence II. Criminal Traffic Offenses III. Civil Traffic Infractions IV. Arrest, Search and Seizure V. Torts/Accident Cases VI. Drivers’ Licenses VII. Red-light Camera Cases VIII. County Court Orders I. Driving Under the Influence (DUI) State v. Browne, __ So. 3d __, 2016 WL 1062793 (Fla. 5th DCA 2016) When the defendant was 21 he committed burglary of a dwelling and petit theft and was sentenced to probation. After the defendant committed a second violation of probation (DUI), when he was 23, the trial court made a downward departure in his sentence, based on his lack of prior record, the nature of the crimes, and the defendant’s age. The state appealed the downward departure, and the appellate court reversed, stating: “Youthful age, alone, is not sufficient proof of the aforementioned mitigating factor. -

Ohio Traffic Rules

OHIO TRAFFIC RULES Rule 1 Scope of rules; applicability; authority and construction 2 Definitions 3 Complaint and summons; form; use 4 Bail and security 5 Joinder of offense and defendants; consolidation for trial; relief from prejudicial joinder 6 Summons, warrants: form, service and execution 7 Procedure upon failure to appear 8 Arraignment 9 Jury demand 10 Pleas; rights upon plea 11 Pleadings and motions before plea and trial: defenses and objections 12 Receipt of guilty plea or No Contest Plea 13 Traffic violations bureau 13.1 Juvenile traffic violations bureau 14 Magistrates 15 Violation of rules 16 Judicial conduct 17 Traffic case scheduling 18 Continuances 19 Rule of court 20 Procedure not otherwise specified 21 Forms 22 [Reserved] 23 Title 24 Effective date 25 Effective date of amendments Temp Temporary provision Multi-Count Uniform Traffic Ticket Commission on the rules of superintendence for Ohio courts Uniform Traffic Ticket (MUTT) RULE 1. Scope of Rules; Applicability; Authority and Construction (A) Applicability. These rules prescribe the procedure to be followed in all courts of this state in traffic cases and supersede the "Ohio Rules of Practice and Procedure in Traffic Cases For All Courts Inferior To Common Pleas" effective January 1, 1969, and as amended on January 4, 1971, and December 7, 1972. (B) Authority and construction. These rules are promulgated pursuant to authority granted the Supreme Court by R.C. 2935.17 and 2937.46. They shall be construed and applied to secure the fair, impartial, speedy and sure administration of justice, simplicity and uniformity in procedure, and the elimination of unjustifiable expense and delay. -

The Road Traffic Act

ROAD TRAFFIC THE ROAD TRAFFIC ACT ARRANGEMENT OF SECTIONS PART I. Preliminan; 1. Short title. 2. Intelpretation. 3. Establishment of Road Traffic Control Authority and branches thereof. 4. Delegation of functions by Traffic Authoritics. 5. Duties of Island TI.affic and Traffic Area Authorities. 6. [Repealed hyAct 13 of lY87.j 7. Delegation of functions by Liccnsing Authority. 8. Valid@ of proceedings of Island Traffic Authority, Trafic Arca Authorities and Licensing Authoritics. PART 11. Regulation ofMolor Vehicles 9. Application of this Part. 10. Certificate of fitness. 1 1. Classification of motor veluclcs. Licensing and Registration of Motor Vehicles 12. Licence duties on motor vchiclcs. 13. Duration of licences. 14. Motor Vehiclc Register. 15. Payment of licence dutics and fccs into Consolidatcd Fund and Parochial Rcvcnue Fund and thc Road Maintenancc Fund. 1.icence.s ofjkivers 16. Drivers’ Liccnccs rcquircd. 17. Licensing of drivers. 18. Prerequisites to the pntof a drivcr’s liccncc. 19. Disqualificationsfor obtaining a dnvcr’s liccncc. 19A. Grounds for fefusal or canccllation of drivcr’s liccnccs [The inclusion of this page is authorized by L.N. 88/20031 3 211. Proixions as to physical fitness of applicants for dn\.ers' licences. 21. Constitutron of Road TraRic Appeal Tribunal. 22. Production of driver's licence to constable on request. 23. Disqualification for offcnccs. 2-1. Provisions as to disqualifications and suspensions. 25. Pro\ isions as to endorsements. Provisions as to Driving mid (?fencesin ~oiiiie~tioii/herew.ith 26. Ratc of spccd on prcscribcd roads. 27. Reckless or dangerous driving. 28. Power to convict for rccklcss or dangcrous driving on trial for manslaughter. -

Digest of Ohio Motor Vehicle Laws

Published and prepared by: Ohio Department of Public Safety P.O. Box 182081, Columbus, Ohio 43218-2081 An Equal Opportunity Employer To order additional copies, please call (614) 466-4775, or visit www.publicsafety.ohio.gov To schedule a road test, visit: www.ohiodrivingtest.com TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 - DRIVER LICENSING & VEHICLE REGISTRATION (In-State) ...................................... 1 How to Obtain an Ohio Driver License ..................................................................1 Scoring ..................................................................................................................5 Renewing Your License .........................................................................................9 Duplicate Licenses ..............................................................................................10 Holders of a Foreign Driver License ...................................................................10 Regulations Regarding License Use ..................................................................10 Organ Donor Information .....................................................................................11 Living Will ............................................................................................................12 Titling a Motor Vehicle .........................................................................................12 License Plate Information ...................................................................................13 2 - DRIVER LICENSING & VEHICLE REGISTRATION