Guidance for Best Practice for the Treatment of Human Remains Excavated from Christian Burial Grounds in England Second Edition

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

London Appleby Deaths 1563-1925.Xlsx

Appleby deaths and burials in London and the South East containing entries from the GRO index and burials from Parish Records updated 03/06/2016 record name yr of birth day month year abode, other details parish district / GRO details line source county Burial Agnes Appleby 4 Oct 1563 St Botolph Bishopsgate, London Middx LMA online Burial Alice Apleby 3 Aug 1563 St Botolph Bishopsgate, London Middx LMA online Burial Anthonie Appleby 29 Jul 1563 St Giles Cripplegate, London Middx LMA online Burial William Apleby 29 Jun 1563 St Botolph Bishopsgate, London Middx LMA online Burial Frances Applebye 8 May 1564 St Leonard Shoreditch, Middlesex Middx LMA online Burial Agnes Appleby 27 Dec 1565 St John The Baptist, Hillingdon, Middlesex Middx LMA online Burial Joane Applebie 9 Aug 1565 All Saints, Edmonton, Middlesex Middx LMA online Burial Joane Applebit 9 Aug 1565 All Saints, Edmonton, Middlesex Middx LMA online Burial Harre Appilbe 22 Jul 1566 St Saviour, Surrey Middx LMA online Burial Richard Appelbe 3 Nov 1567 St Andrew Holborn, London Middx LMA online Burial Margaret Applebie 1 Apr 1569 a child St Olave Hart Street, London City of London FreeREG Burial William Appleby 21 Aug 1570 St James Garlickhithe, London Middx LMA online Burial Willm Appleby 21 Aug 1570 St James Garlickhithe, London Middx LMA online Burial Rychard Appelbye 16 Dec 1571 St Saviour, Denmark Park, Surrey Middx LMA online Burial John Appleby 1572 Westminster St Margaret Middx Boyds London Burial Index LMA online Burial Rob. Appleby 1573 Westminster St Margaret Middx Boyds London Burial Index LMA online Burial Thomas Appelbye 16 Apr 1573 St Saviour, Denmark Park, Surrey Middx LMA online Burial Elizabeth Appelbye 7 Aug 1574 St Saviour, Surrey Middx LMA online Burial John Appleby 5 Oct 1575 St Giles, South Mimms, Hertfordshire Middx LMA online Burial John Appleby 10 Oct 1575 St Giles, South Mimms, Hertfordshire Middx LMA online Burial Bettrice Appleby 29 Aug 1577 father - Robert St Gregory By St Paul, London Middx LMA online Burial Dav. -

Happy Easter to All from Your Local News Magazine for the Two Dales PRICELESS

REETH AND DISTRICT GAZETTE LTD ISSUE NO. 193 APRIL 2012 Happy Easter to all from your local news magazine for the Two Dales PRICELESS 2 REETH AND DISTRICT GAZETTE LTD CHURCH NOTICES in Swaledale & Arkengarthdale st 1 April 9.15 am St. Mary’s Muker Eucharist - Palm Sunday 10.30 am Low Row URC Reeth Methodist 11.00 am Holy Trinity Low Row Eucharist St. Edmund’s Marske Reeth Evangelical Congregational Eucharist 2.00 pm Keld URC 6.00 pm St. Andrew’s, Grinton Evening Prayer BCP 6.30 pm Gunnerside Methodist Reeth Evangelical Congregational th 5 April 7.30 pm Holy Trinity Low Row Eucharist & Watch 8.00 pm St. Michael’s Downholme Vigil th 6 April 9.00 am Keld – Corpse Way Walk - Good Friday 11.00 am Reeth Evangelical Congregational 12.00 pm St Mary’s Arkengarthdale 2.00 pm St. Edmund’s Marske Devotional Service 3.00 pm Reeth Green Meet 2pm Memorial Hall Open Air Witness th 7 April – Easter Eve 8.45 pm St. Andrew’s, Grinton th 8 April 9.15 am St. Mary’s, Muker Eucharist - Easter Sunday 9.30 am St. Andrew’s, Grinton Eucharist St. Michael’s, Downholme Holy Communion 10.30 am Low Row URC Holy Communion Reeth Methodist All Age Service 11.00 am Reeth Evangelical Congregational St. Edmund’s Marske Holy Communion Holy Trinity Low Row Eucharist 11.15 am St Mary’s Arkengarthdale Holy Communion BCP 2.00 pm Keld URC Holy Communion 4.30 pm Reeth Evangelical Congregational Family Service followed by tea 6.30 pm Gunnerside Methodist with Gunnerside Choir Arkengarthdale Methodist Holy Communion th 15 April 9.15 am St. -

Burial Act 1852

Status: This is the original version (as it was originally enacted). Burial Act 1852 1852 CHAPTER 85 An Act to amend the Laws concerning the Burial of the Dead in the Metropolis. [1st July 1852] WHEREAS it is expedient to repeal " The Metropolitan Interments Act, 1850, " and to make such other Provision as herein-after mentioned in relation to Interments in and near the Metropolis: Be it therefore enacted by the Queen's most Excellent Majesty, by and with the Advice and Consent of the Lords Spiritual and Temporal, and Commons, in this present Parliament assembled, and by the Authority of the same, as follows : I 13 & 14 Vict. c.52 repealed, and Her Majesty may continue additional Member of Board therein authorized. The said Act shall be repealed: Provided always, that it shall be lawful for Her Majesty to continue during the Continuance of the General Board of Health the Appointment of the additional Member of such Board authorized by the said Act, and the Salary of such Member, fixed as in the said Act mentioned, shall be paid as by Section Seven of the Public Health Act, 1848, is directed concerning the Salaries therein mentioned. II On Representation of Secretary of State, Her Majesty in Council may order Discontinuance of Burials in any Part of the Metropolis. In case it appear to Her Majesty in Council, upon the Representation of One of Her Majesty's Principal Secretaries of State, that for the Protection of the Public Health Burials in any Part or Parts of the Metropolis, or in any Burial Grounds or Places of Burial in the Metropolis, should be wholly discontinued, or should be discontinued subject to any Exception or Qualification, it shall be lawful for Her Majesty, by and with the Advice of Her Privy Council, to order that after a Time mentioned in the Order Burials in such Part or Parts of the Metropolis or in such Burial Grounds or Places of Burial shall be discontinued wholly, or subject to any Exceptions or Qualifications 2 Burial Act 1852 (c. -

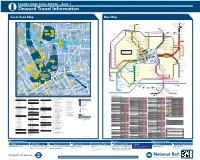

London Kings Cross Station – Zone 1 I Onward Travel Information Local Area Map Bus Map

London Kings Cross Station – Zone 1 i Onward Travel Information Local Area Map Bus Map 1 35 Wellington OUTRAM PLACE 259 T 2 HAVELOCK STREET Caledonian Road & Barnsbury CAMLEY STREET 25 Square Edmonton Green S Lewis D 16 L Bus Station Games 58 E 22 Cubitt I BEMERTON STREET Regent’ F Court S EDMONTON 103 Park N 214 B R Y D O N W O Upper Edmonton Canal C Highgate Village A s E Angel Corner Plimsoll Building B for Silver Street 102 8 1 A DELHI STREET HIGHGATE White Hart Lane - King’s Cross Academy & LK Northumberland OBLIQUE 11 Highgate West Hill 476 Frank Barnes School CLAY TON CRESCENT MATILDA STREET BRIDGE P R I C E S Park M E W S for Deaf Children 1 Lewis Carroll Crouch End 214 144 Children’s Library 91 Broadway Bruce Grove 30 Parliament Hill Fields LEWIS 170 16 130 HANDYSIDE 1 114 CUBITT 232 102 GRANARY STREET SQUARE STREET COPENHAGEN STREET Royal Free Hospital COPENHAGEN STREET BOADICEA STREE YOR West 181 212 for Hampstead Heath Tottenham Western YORK WAY 265 K W St. Pancras 142 191 Hornsey Rise Town Hall Transit Shed Handyside 1 Blessed Sacrament Kentish Town T Hospital Canopy AY RC Church C O U R T Kentish HOLLOWAY Seven Sisters Town West Kentish Town 390 17 Finsbury Park Manor House Blessed Sacrament16 St. Pancras T S Hampstead East I B E N Post Ofce Archway Hospital E R G A R D Catholic Primary Barnsbury Handyside TREATY STREET Upper Holloway School Kentish Town Road Western University of Canopy 126 Estate Holloway 1 St. -

Durham E-Theses

Durham E-Theses The development of education in the North Ridings of Yorkshire 1902 - 1939 Jennings, E. How to cite: Jennings, E. (1965) The development of education in the North Ridings of Yorkshire 1902 - 1939, Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/9965/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk Abstract of M. Ed. thesis submitted by B. Jennings entitled "The Development of Education in the North Riding of Yorkshire 1902 - 1939" The aim of this work is to describe the growth of the educational system in a local authority area. The education acts, regulations of the Board and the educational theories of the period are detailed together with their effect on the national system. Local conditions of geograpliy and industry are also described in so far as they affected education in the North Riding of Yorkshire and resulted in the creation of an educational system characteristic of the area. -

Death, Time and Commerce: Innovation and Conservatism in Styles of Funerary Material Culture in 18Th-19Th Century London

Death, Time and Commerce: innovation and conservatism in styles of funerary material culture in 18th-19th century London Sarah Ann Essex Hoile UCL Thesis submitted for the degree of PhD Declaration I, Sarah Ann Essex Hoile confirm that the work presented in this thesis is my own. Where information has been derived from other sources, I confirm that this has been indicated in the thesis. Signature: Date: 2 Abstract This thesis explores the development of coffin furniture, the inscribed plates and other metal objects used to decorate coffins, in eighteenth- and early nineteenth-century London. It analyses this material within funerary and non-funerary contexts, and contrasts and compares its styles, production, use and contemporary significance with those of monuments and mourning jewellery. Over 1200 coffin plates were recorded for this study, dated 1740 to 1853, consisting of assemblages from the vaults of St Marylebone Church and St Bride’s Church and the lead coffin plates from Islington Green burial ground, all sites in central London. The production, trade and consumption of coffin furniture are discussed in Chapter 3. Chapter 4 investigates coffin furniture as a central component of the furnished coffin and examines its role within the performance of the funeral. Multiple aspects of the inscriptions and designs of coffin plates are analysed in Chapter 5 to establish aspects of change and continuity with this material. In Chapter 6 contemporary trends in monuments are assessed, drawing on a sample recorded in churches and a burial ground, and the production and use of this above-ground funerary material culture are considered. -

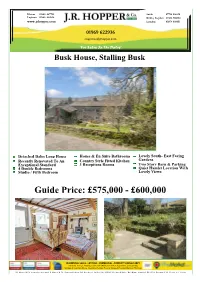

Guide Price: £575000

Hawes 01969 667744 Settle 07726 596616 Leyburn 01969 622936 Kirkby Stephen 07434 788654 www.jrhopper.com London 02074 098451 01969 622936 [email protected] “For Sales In The Dales” Busk House, Stalling Busk Detached Dales Long House House & En Suite Bathrooms Lovely South- East Facing Recently Renovated To An Country Style Fitted Kitchen Gardens Exceptional Standard 3 Receptions Rooms Two Story Barn & Parking 4 Double Bedrooms Quiet Hamlet Location With Studio / Fifth Bedroom Lovely Views Guide Price: £575,000 - £600,000 RESIDENTIAL SALES • LETTINGS • COMMERCIAL • PROPERTY CONSULTANCY Valuations, Surveys, Planning, Commercial & Business Transfers, Acquisitions, Conveyancing, Mortgage & Investment Advice, Inheritance Planning, Property, Antique & Household Auctions, Removals J. R. Hopper & Co. is a trading name for J. R. Hopper & Co. (Property Services) Ltd. Registered: England No. 3438347. Registered Office: Hall House, Woodhall, DL8 3LB. Directors: L. B. Carlisle, E. J. Carlisle Busk House, Stalling Busk, Askrigg DESCRIPTION Busk House is traditional Dales long house located in the little known valley of Raydale in Upper Wensleydale. Stalling Busk is a pretty farming village with a small church and is situated at the south end of Semerwater, the second largest natural lake in Yorkshire, and a haven for wildlife & flowers. It is only 3 miles from the village of Bainbridge with a primary school & chapel, pub, butcher's shop, garage & shop and 5 miles from the Market Town of Hawes with a good range of amenities including doctor's surgery and school. The property is believed to date back to 1685. It boasts a wealth of charm with its original character features including stone mullions, original cheese shelves, beams and feature wall niches. -

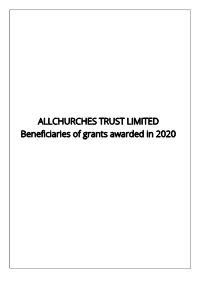

Allchurches Trust Beneficiaries 2020

ALLCHURCHES TRUST LIMITED Beneficiaries of grants awarded in 2020 1 During the year, the charity awarded grants for the following national projects: 2020 £000 Grants for national projects: 4Front Theatre, Worcester, Worcestershire 2 A Rocha UK, Southall, London 15 Archbishops' Council of the Church of England, London 2 Archbishops' Council, London 105 Betel UK, Birmingham 120 Cambridge Theological Federation, Cambridge, Cambridgeshire 2 Catholic Marriage Care Ltd, Nottingham, Nottinghamshire 16 Christian Education t/a RE Today Services, Birmingham, West Midlands 280 Church Pastoral Aid Society (CPAS), Coventry, West Midlands 7 Counties (formerly Counties Evangelistic Work), Westbury, Wiltshire 3 Cross Rhythms, Stoke-on-Trent, Staffordshire 3 Fischy Music, Edinburgh 4 Fusion, Loughborough, Leicestershire 83 Gregory Centre for Church Multiplication, London 350 Home for Good, London 1 HOPE Together, Rugby, Warwickshire 17 Innervation Trust Limited, Hanley Swan, Worcestershire 10 Keswick Ministries, Keswick, Cumbria 9 Kintsugi Hope, Boreham, Essex 10 Linking Lives UK, Earley, Berkshire 10 Methodist Homes, Derby, Derbyshire 4 Northamptonshire Association of Youth Clubs (NAYC), Northampton, Northamptonshire 6 Plunkett Foundation, Woodstock, Oxfordshire 203 Pregnancy Centres Network, Winchester, Hampshire 7 Relational Hub, Littlehampton, West Sussex 120 Restored, Teddington, Middlesex 8 Safe Families for Children, Nottingham, Nottinghamshire 280 Safe Families, Newcastle-upon-Tyne, Tyne and Wear 8 Sandford St Martin (Church of England) Trust, -

The Anglo-Catholic Companion to Online Church

content regulars Vol 23 No 292 July/August 2020 19 THE WAy WE LIVE nOW cHRISTOPHER SmITH 3 LEAD STORy 20 Views, reviews & previews is listening ‘Replying we sing as one individual...’ ART : Owen Higgs on 25 gHOSTLy cOunSEL Exhibitions in Lockdown AnDy HAWES Barry A Orford encourages wants to save the book unity amongst Catholic BOOkS: John Twisleton on An Anglicans Astonishing Secret Andrew Hawes on EDITORIAL 18 3 The Anglo-catholic Pointers to Heaven BISHOPS Of THE SOcIETy 35 companion to Online church Jack Allen on Why LukE WALfORD Medieval Philosophy introduces a new resource Maers William Davage on a 26 SAInT QuEnTIn 4 World Peace Day Primrose Path J A LAn SmITH Barry A Orford on 29 SummER DIARy calls for an act of reconciliation Evelyn Underhill THuRIfER continues in lockdown 5 Anglo-catholicism in 32 The resurrection of a special Lancashire church 31 fAITH Of OuR fATHERS TOm HODgSOn kEVIn cABLE ARTHuR mIDDLETOn considers the legacy of Bishop is moving to Jaffa on staying orthodox Baddeley 35 corpus christi in Bickley 34 TOucHIng PLAcE 8 The Wesley Brothers and the Ss Just et Pasteur, Valcabrere, France Eucharist RyAn n D AnkER encourages us to read Wesley’s hymns 11 Lauda Sion HARRI WILLIAmS on a very different Corpus Christi 11 A message from the Director of forward in faith 12 Who? me? mIcHAEL fISHER is called 14 meeting mrs Scudamore ELEAnOR RELLE introduces a Catholic pioneer 16 Ecce Sacerdos magnus ROgERS cASWELL remembers Fr Brandie E R E G Adoration for Corpus Christi V A at St Mary’s, Walsingham. -

Yorkshire Dales National Park Local Plan 2015-2030 the Local Plan Was Adopted on 20 December 2016

Yorkshire Dales National Park Local Plan 2015-2030 The Local Plan was adopted on 20 December 2016. It does not cover the parts of Eden District, South Lakeland or Lancaster City that have been designated as part of the extended National Park from 1 August 2016. The Local Plan is accompanied by a series of policies maps that provide the spatial expression of some of the policies. The maps show land designations - for example, where land is protected for wildlife purposes. They also show where land is allocated for future development. The policies maps can be found on the Authority’s website in the Planning Policy section at www.yorkshiredales.org.uk/policies-maps 1 Introduction 1 L4 Demolition and alteration of 77 traditional farm buildings 2 Strategic Policies L5 Heritage assets - enabling 79 SP1 Sustainable development 10 development SP2 National Park purposes 12 L6 Crushed rock quarrying 81 SP3 Spatial strategy 14 L7 Building stone 85 SP4 Development quality 18 L8 Reworking mineral waste 86 SP5 Major development 21 L9 Mineral and railhead 87 safeguarding 3 Business & Employment L10 The open upland 89 BE1 Business development sites 24 BE2 Rural land-based enterprises 26 6 Tourism BE3 Re-use of modern buildings 28 T1 Camping 92 BE4 New build live/work units 30 T2 Touring caravan sites 94 BE5 High street service frontages 32 T3 Sustainable self-catering 96 BE6 Railway-related development 34 visitor accommodation BE7 Safeguarding employment 36 T4 Visitor facilities 99 uses T5 Indoor visitor facilities 101 4 Community 7 Wildlife C1 Housing -

Environmental Legislation and Other Requirements Register

SUSTAINABILITY AND CONSENTS – ENVIRONMENTAL MANAGEMENT Crossrail Environmental Legislation And Other Requirements Register Document Number: CR-XRL-T1-GPR-CR001-00005 Current Document History: Revision Effective Author(s) Reviewed by: Approved Reason for Issue: Date: (‘Owner’ in eB *) (‘Checked by’ in eB *) by: 11.0 17-12-15 Updated to reflect updates on legislation 6 monthly 10.0 21 February Updated to reflect 2015 updates on legislation and new Crossrail document template layout Learning Legacy Document © Crossrail Limited CRL RESTRICTED Template: CR-XRL-O4-ZTM-CR001-00001 Rev 8.0 Crossrail Environmental Legislation And Other Requirements Register CR-XRL-T1-GPR-CR001-00005 Rev 11.0 Previous Document History: Revision Prepared Author: Reviewed by: Approved by: Reason for Revision Date: 9.0 28 February Updated to reflect updates 2014 on legislation 6 monthly 8.0 26 June 2013 Updated to reflect updates on legislation 6 monthly 7.0 14 Dec 2012 Updated to reflect updates on legislation 6 monthly 6.0 27 June Updated to reflect updates 2012 on legislation 6 monthly 5.0 13 Sep 11 Comments on Rev 4.0 issued for review 4.0 31-08-2011 Updated to reflect re- organisation and updates to legislation. Revision Changes: Revision Status / Description of Changes 11.0 Updated to reflect updates on legislation 6 monthly Learning Legacy Document © Crossrail Limited CRL RESTRICTED Template: CR-XRL-O4-ZTM-CR001-00001 Rev 8.0 Crossrail Environmental Legislation And Other Requirements Register CR-XRL-T1-GPR-CR001-00005 Rev 11.0 Contents Air Quality ....................................................................................................... -

Burial and Cremation Law Reform

BURIAL AND CREMATION LAW REFORM A RESPONSE BY A WORKING PARTY OF THE ECCLESIASTICAL LAW SOCIETY TO THE LAW COMMISSION’S CONSULTATION PAPER: ‘BURIAL AND CREMATION: IS THE LAW GOVERNING BURIAL AND CREMATION FIT FOR MODERN CONDITIONS?’ 1. The Ecclesiastical Law Society 1.1. The Ecclesiastical Law Society is a charity whose object is ‘to proMote education in ecclesiastical law for the benefit of the public, including in particular: (a) the clergy and laity of the Church of England and (b) those who May hold authority or judicial office in, or practise in the ecclesiastical courts of the Church of England’. 1.2. The Society has approxiMately 700 MeMbers, Mostly Anglican and resident in the UK, but includes a significant nuMber froM other Christian denoMinations and froM overseas. It publishes the Ecclesiastical Law Journal and circulates newsletters, as well as organising conferences and seminars for Members and non- members. It is active in promoting the teaching of ecclesiastical law at theological colleges and as a coMponent of continuing Ministerial education. 1.3. It has established Many working parties on Matters over the past thirty years concerning the ecclesiastical law. 1.4. Professor Nick Hopkins sought the views of the Society on the Law CoMMission’s current project as part of its thirteenth prograMMe of law reform. The Society established a Burial Law Review Working Party in order to do so.1 This response has been endorsed by the ComMittee of the Ecclesiastical Law Society and is subMitted to the Law CoMMission with its approval. 2. Some initial thoughts on the current issues Consolidation as a minimum 2.1.