Revolving Door

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

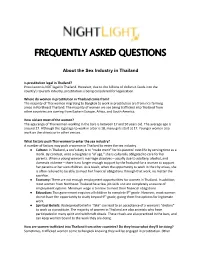

Frequently Asked Questions

FREQUENTLY ASKED QUESTIONS About the Sex Industry in Thailand Is prostitution legal in Thailand? Prostitution is NOT legal in Thailand. However, due to the billions of dollars it feeds into the country’s tourism industry, prostitution is being considered for legalization. Where do women in prostitution in Thailand come from? The majority of Thai women migrating to Bangkok to work in prostitution are from rice farming areas in Northeast Thailand. The majority of women we see being trafficked into Thailand from other countries are coming from Eastern Europe, Africa, and South America. How old are most of the women? The age range of Thai women working in the bars is between 17 and 50 years old. The average age is around 27. Although the legal age to work in a bar is 18, many girls start at 17. Younger women also work on the streets or in other venues. What factors push Thai women to enter the sex industry? A number of factors may push a woman in Thailand to enter the sex industry. ● Culture: In Thailand, a son’s duty is to “make merit” for his parents’ next life by serving time as a monk. By contrast, once a daughter is “of age,” she is culturally obligated to care for her parents. When a young woman’s marriage dissolves—usually due to adultery, alcohol, and domestic violence—there is no longer enough support by the husband for a woman to support her parents or her own children. As a result, when the opportunity to work in the city arises, she is often relieved to be able to meet her financial obligations through that work, no matter the sacrifice. -

An Overview of Male Sex Work in Edinburgh and Glasgow: the Male Sex Worker Perspective

An Overview of Male Sex Work in Edinburgh and Glasgow: The Male Sex Worker Perspective Judith Connell & Graham Hart MRC Social & Public Health Sciences Unit Occasional Paper No.8 June 2003 Medical Research Council Medical Research Health Sciences Unit Social & Public MRC Social and Public Health Sciences Unit Acknowledgements We would like to acknowledge and thank the following individuals and groups without whom this research and subsequent report would have been impossible: • The male sex workers who talked freely and openly about prostitution and related personal experiences. • The outreach workers at Lothian Primary Care NHS Trust (The ROAM Team) and Phace Scotland. Special thanks to Mark Bailie, Grace Cardozo, Tom Lusk, Andrew O’Donnell and David Pryde. 1 MRC Social and Public Health Sciences Unit Contents Acknowledgements .......................................................................................... 1 Glossary ........................................................................................................... 4 1. Introduction................................................................................................... 6 Background................................................................................................... 6 The Current Study ........................................................................................ 8 2. Research Aims, Objectives, Methodology & Limitations ............................ 10 2.1 Research Aims & Objectives............................................................... -

New Economies of Sex and Intimacy in Vietnam by Kimberly Kay Hoang

New Economies of Sex and Intimacy in Vietnam by Kimberly Kay Hoang A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Sociology and the Designated Emphasis in Women, Gender, and Sexuality in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Raka Ray, Chair Professor Barrie Thorne Professor Irene Bloemraad Professor Peter Zinoman Fall 2011 New Economies of Sex and Intimacy Copyright 2011 by Kimberly Kay Hoang Abstract New Economies of Sex and Intimacy in Vietnam by Kimberly Kay Hoang Doctor of Philosophy in Sociology and the Designated Emphasis in Women, Gender, and Sexuality University of California, Berkeley Professor Raka Ray, Chair Over the past two decades, scholars have paid particular attention to the growth of global sex tourism, a trade marked by convergence between the global and local production and consumption of sexual services. In the increasingly global economy, the movement of people and capital around the world creates new segments of sex work, with diverse groups of consumers and providers. This dissertation examines the dialectical link between intimacy and political economy. I examine how changes in the global economy structure relations of intimacy between clients and sex workers; and how intimacy can be a vital form of currency that shapes economic and political relations. I trace new economies of sex and intimacy in Vietnam by moving from daily worlds of sex work in Ho Chi Minh City [HCMC] to incorporate a more structural and historical analysis. Drawing on 15 months of ethnography (2009-2010) working as a bartender and hostess I analyze four different bars that cater to wealthy local Vietnamese men and their Asian business partners, overseas Vietnamese men living in the diaspora, Western expatriates, and Western budget travelers. -

Sex Work in Asia I

WORLD HEALTH ORGANIZATION Regional Office for the Western Pacific SSEEXX WWOORRKK IINN AASSIIAA JULY 2001 SSeexx WWoorrkk IInn AAssiiaa Contents Acknowledgements ii Abbreviations iii Introduction 1 Sources and methodology 1 The structure of the market 2 The clients and the demand for commercial sex 3 From direct to indirect prostitution – and the limitations of statistical analysis 5 Prostitution and the idea of ‘choice’ 6 Trafficking, migration and the links with crime 7 The demand for youth 8 HIV/AIDS 9 Male sex workers 10 Country Reports Section One: East Asia Japan 11 China 12 South Korea 14 Section Two: Southeast Asia Thailand 15 Cambodia 17 Vietnam 18 Laos 20 Burma 20 Malaysia 21 Singapore 23 Indonesia 23 The Philippines 25 Section Three: South Asia India 27 Bangladesh. 30 Sri Lanka 31 Nepal 32 Pakistan 33 Sex Work in Asia i ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS WHO wish to thank Dr. Louise Brown for her extensive research and preparation of this report. Special thanks to all those individuals and organisations that have contributed and provided information used in this report. Sex Work in Asia ii ABBREVIATIONS AIDS Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome FSW Female sex worker HIV Human Immunodeficiency Virus MSM Men who have sex with men MSW Male sex worker NGO Non-governmental organisation STD Sexually transmitted disease Sex Work in Asia iii INTRODUCTION The sex industry in Asia is changing rapidly. It is becoming increasingly complicated, with highly differentiated sub sectors. The majority of studies, together with anecdotal evidence, suggest that commercial sex is becoming more common and that it is involving a greater number of people in a greater variety of sites. -

Labor Violations and Discrimination in the Clark County Outcall Entertainment Industry

UNLV Retrospective Theses & Dissertations 1-1-2003 Labor violations and discrimination in the Clark County outcall entertainment industry Candice Michelle Seppa Arroyo University of Nevada, Las Vegas Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalscholarship.unlv.edu/rtds Repository Citation Seppa Arroyo, Candice Michelle, "Labor violations and discrimination in the Clark County outcall entertainment industry" (2003). UNLV Retrospective Theses & Dissertations. 1555. http://dx.doi.org/10.25669/nqi9-s0j7 This Thesis is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by Digital Scholarship@UNLV with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Thesis in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/ or on the work itself. This Thesis has been accepted for inclusion in UNLV Retrospective Theses & Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Scholarship@UNLV. For more information, please contact [email protected]. IÎ4 TTHis (:Lj%j%jc(:(]Tjnsri"%(:MLrr\:L4JLi, ENTERTAINMENT INDUSTRY by Candice Michelle Seppa Arroyo Associate o f Arts Simon's Rock C o llie o f Bard 1994 Bachelor o f Arts University o f Minnesota, Mortis 1998 A thesis submitted in partial fulfillm ent o f the requirements for the M aster of Arts Degree in Sociology Department of Sociology College of Liberal Arts Graduate College University of Nevada, Las Vegas August 2003 Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. -

Ethical Dilemma's in Sex Work Research

JUNE 2004 7 Sex workers health, HIV/AIDS, and ethical issues in care & research HIV prevention and health promotion in prostitution and health promotion HIV prevention EDITORIAL In the very first issue of Research for Sex Work, in 1998, Sue Moving beyond STIs Metzenrath from Australia wrote: “For far too long researchers On the positive side is the contribution from Gabriela Irrazabal, have been using sex workers as guinea pigs without any benefit who describes how the Argentinean sex workers’ union accruing to sex workers as the result of research. Essentially aca- AMMAR fights discrimination in health-care settings. Other demic careers are made on our backs. Further, some research community-based organisations have found similar solutions. has provided ammunition to those who want to suppress the However, some practices remain unacceptable. Veronica Monet sex industry and research findings have been used to support explains how sex-negative attitudes in the USA lead to biased some of those arguments. In many countries sex workers views of policy makers and researchers, which in turn lead to already refuse to be involved in research because they can’t see practices like mandatory testing. anything in it for them. After all, why would sex workers give An important step would be to move beyond thinking that STI freely of their information and knowledge and then it is used to treatment is the primary goal of health care for sex workers and suppress their livelihood?” STI research the primary goal of sex work research, as William Stigmatisation and discrimination are key factors that have an Wong and Ann Gray from Hong Kong stress in their article. -

Human Trafficking Poster in English and Spanish

Victims of slavery and human trafficking Las víctimas de esclavitud y trata de personas are protected under United States and Illinois law están protegidas bajo las leyes de Estados Unidos y de Illinois If you or someone you know: Si usted o alguien que usted conoce: • Is being forced to engage in any activity and cannot leave, • Es forzado a participar en cualquier actividad y no puede whether it is: dejarla, ya sea de: • Commercial sex industry (street prostitution, strip clubs, • La industria del sexo comercial (prostitución callejera, clubes, salas de masaje, servicios de acompañante, burdeles, Internet) massage parlors, escort services, brothels, internet), • Residencias privadas (trabajo doméstico, cuidado de niños, • Private Homes (housework, nannies, servile marriages), matrimonios serviles) • Farm work, landscaping, construction, • Trabajo en fincas, jardinería, construcción. • Factory (industrial, garment, meat-packing), • Fábricas (industrial, textil, empacado de carnes). • Peddling rings, begging rings, or door-to-door sales crews • Grupos de venta ambulante, limosneros o grupos de ventas • Hotel, retail, bars, restaurant work or callejeras • Any other activity • Hoteles, tiendas, bares, trabajo en restaurantes o • Had their passport or identification taken away or • Cualquier otra actividad. • Is being threatened with deportation if they won’t work • Le quitaron su pasaporte u otra forma de identificación. • Le amenazan con deportación si rehúsa trabajar. National Human Trafficking Resource Center Centro Nacional de Recursos Para la Trata de Personas 1-888-373-7888 1-888-373-7888 Or Text “HELP” to 233733 O para acceso a servicios y ayuda, to access help and services. envíe un texto con la palabra “HELP” al 233733 La línea: The hotline is: • Está disponible las 24 horas del día, los 7 días de la semana. -

Norma Jean Almodovar 8801 Cedros Ave

Norma Jean Almodovar 8801 Cedros Ave. Unit 7 Panorama City, CA 91402 Phone: 818-892-2029 Fax: 818-892-2029 call first E-Mail: [email protected] Norma Jean Almodovar is a well known and highly respected international sex worker rights activist and is a popular speaker and published author, including articles in law journals and academic publications. She is currently engaged in researched for a book which exposes the unfortunate and harmful consequences of arbitrary enforcement of prostitution laws. From 1972 to 1982, she was a civilian employee of the Los Angeles Police Department, working as a traffic officer primarily in the Hollywood Division. There she encountered serious police abuse and corruption which she documented in her autobiography, Cop to Call Girl (1993- Simon and Schuster). In 1982 she was involved in an on-duty traffic accident, and being disillusioned by the corruption and societal apathy toward the victims of corruption, she decided not to return to work in any capacity with the LAPD. Instead, she chose to become a call girl, a career that would both give her the financial base and the publicity to launch her crusade against police corruption, particularly when it involved prostitutes. Unfortunately, she incurred the wrath of the LAPD and Daryl Gates when it became known that she was writing an expose of the LAPD, and as a result, she was charged with one count of pandering, a felony, and was ultimately incarcerated for 18 months. During her incarceration, she was the subject of a “60 Minutes” interview with Ed Bradley, who concluded that she was in prison for no other reason than that she was writing a book about the police. -

The Health Implications of Prostitution and Other Relevant Issues

The Health Implications of Prostitution and Other Relevant Issues By John O’Loughlin Citizens Against Prostitution Team Member Introduction My task was to research the health implications of prostitution. I found a great deal of information that helped me understand the most hotly debated issues on a deeper level, and I’ve tried to organize that information here for you. I do not necessarily endorse all of the sources referenced below, but present them to you so that you may analyze them and draw your own conclusions. All in all, there are a few things I’ve read that ring true to me: • Prostitution is not a monolithic issue. There are many different perspectives on prostitution, and none are either all right or all wrong. • In many, many instances, prostitution can have a very detrimental effect on the prostitute. • There is very little reliable data on prostitution. • Current efforts to fight prostitution have not been wholly successful. • If you are certain that prostitution is a victimless crime, you should read “Challenging Men’s Demand for Prostitution in Scotland”. • If you are certain that making prostitution illegal is the answer, read “Redefining Prostitution as Sex Work on the International Agenda”. What follows is a summary of 27 separate articles that I reviewed in my research. I simply pulled quotes from the articles with no editorial additions, and organized them (coarsely) into four categories: 1. statistical and informational (reasonably even-handed presentations of information); 2. anti-prostitution (basic agenda is to end prostitution everywhere) 3. the “johns” (focusing on the demand side of the transaction) and 4. -

Street Prostitution Zones and Crime

Street Prostitution Zones and Crime Paul Bisschop Stephen Kastoryano∗ Bas van der Klaauw April 30, 2015 Abstract This paper studies the effects of introducing legal street prostitution zones on both reg- istered and perceived crime. We exploit a unique setting in the Netherlands where legal street prostitution zones were opened in nine cities under different regulation systems. We provide evidence that the opening of these zones was not in response to changes in crime. Our difference-in-difference analysis using data on the largest 25 Dutch cities between 1994 and 2011 shows that opening a legal street prostitution zone decreases registered sexual abuse and rape by about 30% − 40% in the first two years. For cities which opened a legal street prostitution zone with a licensing system we also find significant reductions in drug crime and long-run effects on sexual assaults. For perceived crime, perceived drug nuisance increases upon opening but then decreases below pre-opening levels in cities with a licensed prostitution zone. In contrast, we find permanent increases in perceived drug crime in the areas adjacent to the legal prostitution zones. Our results do not show evi- dence of spillover effects on crime associated to human trafficking organizations. Keywords: Prostitution, Crime, Sexual Abuse, Rape, Drugs, Regulation. JEL-code: J16, J47, K14, K23, K42. ∗Stephen Kastoryano (corresponding author), University of Mannheim, IZA, e-mail: [email protected]; Paul Bisschop, SEO Economic Research, e-mail: [email protected]; Bas van der Klaauw, VU University Amsterdam, IZA, Tinbergen Institute, e-mail: [email protected] Thanks to Sander Flight, Wim Bernasco, Jan van Ours, Hessel Oosterbeek, Erik Plug, Joop Hartog, Mich`eleTertilt, Rei Sayag and Thomas Buser for valuable comments. -

Employee Rights in Sex Work: the Struggle for Dancers' Rights As Employees

Minnesota Journal of Law & Inequality Volume 14 Issue 2 Article 4 December 1996 Employee Rights in Sex Work: The Struggle for Dancers' Rights as Employees Carrie Benson Fischer Follow this and additional works at: https://lawandinequality.org/ Recommended Citation Carrie Benson Fischer, Employee Rights in Sex Work: The Struggle for Dancers' Rights as Employees, 14(2) LAW & INEQ. 521 (1996). Available at: https://scholarship.law.umn.edu/lawineq/vol14/iss2/4 Minnesota Journal of Law & Inequality is published by the University of Minnesota Libraries Publishing. Employee Rights in Sex Work: The Struggle for Dancers' Rights as Employees Carrie Benson Fischer* Introduction The legal sex industry1 in Minneapolis has boomed in recent years,2 and will likely continue to grow.3 The number of women * J.D., University of Minnesota Law School, expected 1997; B.A., St. Olaf Col- lege, 1993. I gratefully acknowledge Sandra Conroy, Kent Klaudt, Sarah Garb and Amy Chiericozzi for their thoughtful editing. I am especially thankful to Kelly Hol- sopple and the entire staff of WHISPER, to whom this article is dedicated, for provid- ing research materials and personal insight into the sex industry. Finally, I am indebted to the partner of my life, David Fischer, who not only provided me with infinite support and encouragement, but who sincerely understands why this article needed to be written. 1. "Legal sex industry" refers to commercial facilities, bars or clubs, that fea- ture strip shows, nude dancing, and other live entertainment for the sexual gratifica- tion of their patrons. Sexually-oriented clubs typically feature female dancers performing in various ways for an almost entirely male audience. -

Space, Street Prostitution and Women's Human Rights

UNIVERSITY OF PADOVA European Master’s Degree in Human Rights and Democratisation A.Y. 2018/2019 Space, street prostitution and women’s human rights The effects of spatial segregation in the perpetuation of violence against women in prostitution Author: Clara Ferrerons Galeano Supervisor: Lorenza Perini ABSTRACT This thesis analyses the role of Italy in fostering violence against women in street prostitution. Since the National Law 125/2008 on urgent measures on public security was passed in this country, city councils have applied municipal ordinances at the local level that prohibit the practice of outdoor prostitution in the public space, thereby criminalising it. Feminist geographers and urbanists argue that spatial arrangements in the city play a key role in the experience of violence against women in urban spaces. As a socially marginalised group, women in prostitution are extremely vulnerable to violence, which is further emphasised when criminalisation of this practice obliges women to move to peripheric and isolated areas of the city or to start working indoors. Taking Padova as a paradigmatic example of the typology of municipalities that have legislated the most on street prostitution, this thesis critically engages with international women’s human rights standards and argues that two ordinances passed in this city in 2011 and 2014 represent a failure of the State to act with due diligence in preventing, protecting and prosecuting all forms of violence against women as provided in CEDAW and the Istanbul Convention. In addition, this thesis argues that violence against women in prostitution should not be regarded as a side-effect of this activity but rather as a structurally mediated gender-based discrimination that needs to be decidedly recognised as such at the international level if the universality of human rights is to be applied rigorously to all individuals.