Living History As Performance: an Analysis of the Manner in Which Historical Narrative Is Developed Through Performance

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

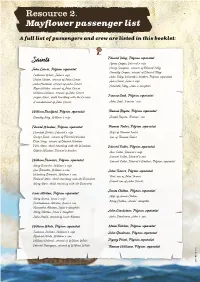

Resource 2 Mayflower Passenger List

Resource 2. Mayflower passenger list A full list of passengers and crew are listed in this booklet: Edward Tilley, Pilgrim separatist Saints Agnus Cooper, Edward’s wife John Carver, Pilgrim separatist Henry Sampson, servant of Edward Tilley Humility Cooper, servant of Edward Tilley Catherine White, John’s wife John Tilley, Edwards’s brother, Pilgrim separatist Desire Minter, servant of John Carver Joan Hurst, John’s wife John Howland, servant of John Carver Elizabeth Tilley, John’s daughter Roger Wilder, servant of John Carver William Latham, servant of John Carver Jasper More, child travelling with the Carvers Francis Cook, Pilgrim separatist A maidservant of John Carver John Cook, Francis’ son William Bradford, Pilgrim separatist Thomas Rogers, Pilgrim separatist Dorothy May, William’s wife Joseph Rogers, Thomas’ son Edward Winslow, Pilgrim separatist Thomas Tinker, Pilgrim separatist Elizabeth Barker, Edward’s wife Wife of Thomas Tinker George Soule, servant of Edward Winslow Son of Thomas Tinker Elias Story, servant of Edward Winslow Ellen More, child travelling with the Winslows Edward Fuller, Pilgrim separatist Gilbert Winslow, Edward’s brother Ann Fuller, Edward’s wife Samuel Fuller, Edward’s son William Brewster, Pilgrim separatist Samuel Fuller, Edward’s Brother, Pilgrim separatist Mary Brewster, William’s wife Love Brewster, William’s son John Turner, Pilgrim separatist Wrestling Brewster, William’s son First son of John Turner Richard More, child travelling with the Brewsters Second son of John Turner Mary More, child travelling -

Insights Vol

international museum theatre alliance insights Vol. 24, No. 3 Summer 2014 Awarding the First Lipsky A Museum Theatre Adventure by Elizabeth A. Pickard Vice-President, IMTAL, and Chair of the Lipsky Panelt On March 14, 2014, five IMTALers had a meeting that they were actually excited to attend. It started with one of those calls that most of us are flattered to receive and also dread—a call to serve on a commit- tee. As it turned out, this meeting was not a ho-hum yawner with people doing other work and eating Skittles while their line was muted. Oh no. This meet- ing was transformative, it was moving, it was exciting, Brenneman Judy Fort Photo: it was personal, and there was conflict—like a really strong museum theatre piece, in fact. Addae Moon, winner of the Jon Lipsky Award for Playwriting Excellence, with Lipsky Panel Chair Elizabeth Of course, strong museum theatre was the very Pickard. reason we were on this conference call. It was the first ever panel meeting to choose the winner of IMTAL’s inaugural Jon Lipsky Award for Playwriting The winning submission, Four Days of Fury by Excellence. The submissions ran the same gamut the Addae Moon of the Atlanta History Center, begins on field does—there were anthropomorphized animals, page 23 in this newsletter, and an interview with the civil rights struggles, trains, romance, mayhem, calls author begins on page 6. continued on page 4 The International Museum Theatre Alliance (IMTAL) is a nonprofit, professional membership organiza- tion and an affiliate to the American Alliance of Museums. -

Enfield Shaker Museum Plan a Visit Today!

E NFIELD S HAKER M U S EU M 2019 PROGRAM GUIDE ENFIELD SHAKER MUSEUM PLAN A VISIT TODAY! Imagine a place so beautiful and serene that the Shakers called it DAILY ADMISSION “Chosen Vale.” General admission includes the intro- Nestled in a valley between Mt. ductory video program, guided tours, Assurance and Mascoma Lake, in exhibits, craft demonstrations, access Enfield, New Hampshire, the En- to other Shaker buildings, the Shak- field Shaker site has been cherished er Cemetery, the Shaker Herb and for over 225 years. At its peak in Production Garden, the Community the mid 19th century, the commu- Garden, the Feast Ground, and 15 nity was home to three “Families” miles of hiking trails. of Shakers. After 130 years of worship, communal living, farming, $12 adults and manufacturing, declining mem- $8 youth 11-17 bership forced the Shakers to close $3 children 6-10 their village and put it up for sale. Free children 5 and under Today the Enfield Shaker Village is Museum Members again a vibrant community. At its $10 Group Rate (6+) heart is the Enfield Shaker Muse- Plenty of Free Parking and Picnic Area um, which is dedicated to preserv- ing the long and rich legacy of the Enfield Shakers. MUSEUM HOURS TABLE OF CONTENTS May 1 - December 21 Become a Member ...................... 3 Facilities Rentals ........................ 3 Daily Youth Exploration Programs ...... 4 10 am - 5 pm Special Events .........................5-8 Center for Advanced Music ......... 8 December 22 - April 30 Monthly Offerings .................9-25 Open by Appointment Only Volunteer Opportunities ...........26 Program Registration ...............27 Please check our website Enfield Shaker Museum www.shakermuseum.org 447 NH Route 4A for our Holiday Hours Enfield, NH 03748 Phone: (603) 632-4346 [email protected] www.shakermuseum.org 2 SUppORT ENFIELD SHAKER MUSEUM Your investment today insures the future of this historic Shaker legacy tomorrow. -

Performing the Knowing Archive: Heritage Performance and Authenticity

Performing the knowing archive: heritage performance and authenticity Dr. Jenny Kidd, City University London Abstract This article presents findings from the Performance, Learning and Heritage project at the University of Manchester 2005-2008. Using evidence from four case studies, it provides insight into the ways visitors to museums and heritage sites utilise their understandings of ‘the authentic’ in making sense of their encounters with performances of the past. Although authenticity is a contested and controversial concept, it remains a significant measure against which our respondents have been influenced by the heritage and tourism industries to analyse and critique their encounters with ‘the past’. Beyond superficial analyses however, it is noted that many respondents demonstrate more sensitive and nuanced reflections on the museum as an authentic authoritative voice, analyses that were aided by the very fictionality of the mode of interpretation. Keywords: performance, authenticity, interpretation, heritage Introduction This article outlines a number of findings from the Performance, Learning and Heritage (PLH) research project at the University of Manchesteri. This three year investigation sought to further understand one of the more controversial and contested forms of interpretation employed at museums and heritage sites; performance. Although a number of small scale research and evaluation projects (often institutional) have been carried out in this field, there has been little sustained investigation into the use and impact -

Historic Costuming Presented by Jill Harrison

Historic Southern Indiana Interpretation Workshop, March 2-4, 1998 Historic Costuming Presented By Jill Harrison IMPRESSIONS Each of us makes an impression before ever saying a word. We size up visitors all the time, anticipating behavior from their age, clothing, and demeanor. What do they think of interpreters, disguised as we are in the threads of another time? While stressing the importance of historically accurate costuming (outfits) and accoutrements for first- person interpreters, there are many reasons compromises are made - perhaps a tight budget or lack of skilled construction personnel. Items such as shoes and eyeglasses are usually a sticking point when assembling a truly accurate outfit. It has been suggested that when visitors spot inaccurate details, interpreter credibility is downgraded and visitors launch into a frame of mind to find other inaccuracies. This may be true of visitors who are historical reenactors, buffs, or other interpreters. Most visitors, though, lack the heightened awareness to recognize the difference between authentic period detailing and the less-than-perfect substitutions. But everyone will notice a wristwatch, sunglasses, or tennis shoes. We have a responsibility to the public not to misrepresent the past; otherwise we are not preserving history but instead creating our own fiction and calling it the truth. Realistically, the appearance of the interpreter, our information base, our techniques, and our environment all affect the first-person experience. Historically accurate costuming perfection is laudable and reinforces academic credence. The minute details can be a springboard to important educational concepts; but the outfit is not the linchpin on which successful interpretation hangs. -

MAYFLOWER RESEARCH HANDOUT by John D Beatty, CG

MAYFLOWER RESEARCH HANDOUT By John D Beatty, CG® The Twenty-four Pilgrims/Couples on Mayflower Who Left Descendants John Alden, cooper, b. c. 1599; d. 12 Sep. 1687, Duxbury; m. Priscilla Mullins, daughter of William. Isaac Allerton, merchant, b. c. 1587, East Bergolt, Sussex; d. bef. 12 Feb. 1658/9, New Haven, CT; m. Mary Norris, who d. 25 Feb. 1620/1, Plymouth. John Billington, b. by 1579, Spalding, Lincolnshire; hanged Sep. 1630, Plymouth; m. Elinor (__). William Bradford, fustian worker, governor, b. 1589/90, Austerfield, Yorkshire; d. 9 May 1657, Plymouth; m. Dorothy May, drowned, Provincetown Harbor, 7 Dec. 1620. William Brewster, postmaster, publisher, elder, b. by 1567; d. 10 Apr. 1644, Duxbury; m. Mary (__). Peter Brown, b. Jan. 1594/5, Dorking, Surrey; d. bef. 10 Oct. 1633, Plymouth. James Chilton, tailor, b. c. 1556; d. 8 Dec 1620, Plymouth; m. (wife’s name unknown). Francis Cooke, woolcomber, b. c. 1583; d. 7 Apr. 1663, Plymouth; m. Hester Mayhieu. Edward Doty, servant, b. by 1599; d. 23 Aug. 1655, Plymouth. Francis Eaton, carpenter, b. 1596, Bristol; d. bef. 8 Nov. 1633, Plymouth. Moses Fletcher, blacksmith, b. by 1564, Sandwich, Kent; d. early 1621, Plymouth. Edward Fuller, b. 1575, Redenhall, Norfolk; d. early 1621, Plymouth; m. (wife unknown). Samuel Fuller, surgeon, b. 1580, Redenhall, Norfolk; d. bef. 28 Oct. 1633, Plymouth; m. Bridget Lee. Stephen Hopkins, merchant, b. 1581, Upper Clatford, Hampshire; d. bef. 17 Jul. 1644, Plymouth; m. (10 Mary Kent (d. England); (2) Elizabeth Fisher, d. Plymouth, 1640s. John Howland, servant, b. by 1599, Fenstanton, Huntingdonshire; d. -

Channel Comparison

STREAMING GUIDE | NETWORK COMPARISONS +Live TV +Live Channel Orange Blue Orange & Blue A&E X X X X X X ABC - KAKE X X ABC News X ACC Network X X S S ACC Network Extra S S Acorn TV P [adult swim] X AMC X X X X X X AMC Premiere P P American Heroes Channel En HL HL HL X Ex Animal Planet X X X X Aspire TV X AXS TV X X X X BabyTV K K K BBC America X X X X X X BBC World News X N N N X Ex beIN SPORTS S S S X beIn SPORTS (2 Spanish, 5 English Channels) X BET L X X X X BET Her X Ex BET Jams Ex BET Soul Ex Bloomberg Television X X X Boomerang X K K K Ex Bravo X X X X X BTN X X X Cartoon Network X X X X X X CBS - KWCH X X X CBS News X X CBS Sports Network X X X CGTN N N N Cheddar Business X X X X X X X Cheddar News X X X X X X = Included in base subscription. Add-ons noted by: A = Adventure Plus, C = Comedy, En = Entertainment, Es = Español/ Spanish, Ex = Extra, HL = Heartland, HW = Hollywood, K = Kids, L = Lifestyle, N = News, P = Premium, S = Sports SKT | SKTC.net | 888.758.8976 Streaming Guide | Network Comparisons | 1 +Live TV +Live Channel Orange Blue Orange & Blue Cinemax P Cinémoi HW HW HW CLEO TV X CMT C C C X X CNBC X X N N X CNBC World X En Ex CNN X X X X X X CNN (Spanish) Es CNN International X Ex CNN - News18 N N N Comedy Central X X X X X COMET X X X X X Cooking Channel En L L L X Ex Cowboy Channel HL HL HL COZI TV X X CuriosityStream P Destination America En HL HL HL X Ex Discovery Channel X X X X X X Discovery (Spanish) Es Discovery Family En X Ex Discovery Familia (Spanish) Es Discovery Life En X Ex Disney Channel X X X X Disney Junior X X K K Disney XD X X K K DIY Network En L L L X Ex Duck TV K K K E! X X X X X EPIX P P P P EPIX Drive-In X X X ESPN X X X X ESPN2 X X X X ESPN3 X X ESPN Bases Loaded X S S ESPN College Extra X ESPN Deportes (Spanish) Es X = Included in base subscription. -

Correct Clothing for Historical Interpreters in Living History Museums Laura Marie Poresky Iowa State University

Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Retrospective Theses and Dissertations Dissertations 1997 Correct clothing for historical interpreters in living history museums Laura Marie Poresky Iowa State University Follow this and additional works at: https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd Part of the American Material Culture Commons, Fashion Design Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Poresky, Laura Marie, "Correct clothing for historical interpreters in living history museums" (1997). Retrospective Theses and Dissertations. 16993. https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd/16993 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Dissertations at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Retrospective Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Correct clothing for historical interpreters in jiving history museums by Laura Marie Poresky A thesis submitted to the graduate faculty in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE Major: Textiles and Clothing Major Professor: Dr. Jane Farrell-Beck Iowa State University Ames. Iowa 1997 II Graduate College Iowa State University This is to certify that the Master's thesis of Laura Marie Poresky has met the thesis requirements of Iowa State University Signatures have been redacted for privacy III TABLE OF CONTENTS ABSTRACT v INTRODUCTlON 1 Justification -

2012 Annual Report Preserve

2012 Annual Report Preserve. Protect. Provide. About This Publication Our 2012 Annual Report exists exclusively in digital format, available on our website at www.FriendsOfTheSmokies.org. In order to further the impact of our donors’ resources for the park’s benefit we chose to publish this report online. If you would like a paper copy, you may print it from home on your computer, or you may request a copy to be mailed to you from our office (800-845-5665). We are committed to conserving natural resources in and around Great Smoky Mountains National Park! Board of Directors • Jan. 1, 2012–Dec. 31, 2012 OFFICERS HONORARY BOARD MEMBERS Rev. Dr. Daniel P. Matthews ..........................Chair Sandy Beall (Maryville, TN) Waynesville, NC Mimi Cecil (Asheville, NC) Dale Keasling .........................................Vice Chair Linda Ogle (Pigeon Forge, TN) Knoxville, TN Deener Matthews (Waynesville, NC) Kay Clayton..............................................Secretary Hal Roberts (Waynesville, NC) Knoxville, TN Jack Williams (Knoxville, TN) Stephen W. Woody ...................................Treasurer Asheville, NC EMERITUS BOARD MEMBERS Justice Gary R. Wade ..................... Chair Emeritus Sevierville, TN John Dickson (Asheville, NC) Natalie Haslam (Knoxville, TN) BOARD MEMBERS Mary Johnson (Shady Valley, TN) Nancy Daves (Knoxville, TN) Kathryn McNeil (San Francisco, CA) Vicky Fulmer (Maryville, TN) Judy Morton (Knoxville, TN) Bruce Hartmann (Knoxville, TN) John B. Waters, Jr. (Sevierville, TN) Luke D. Hyde (Bryson City, NC) David White (Sevierville, TN) John Mason (Asheville, NC) Dr. Myron “Barney” Coulter** (Waynesville, NC) Jim Ogle (Sevierville, TN) Leon Jones** Meridith Elliott Powell (Asheville, NC) Wilma Dykeman Stokely** Mark Williams (Knoxville, TN) Lindsay Young** ** Deceased Friends Staff Jim Hart .......................................................President Holly Scott ................................. -

Folklife Sourcebook: a Directory of Folklife Resources in the United States

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 380 257 RC 019 998 AUTHOR Bartis, Peter T.; Glatt, Hillary TITLE Folklife Sourcebook: A Directory of Folklife Resources in the United States. Second Edition. Publications of the American Folklife Center, No. 14. INSTITUTION Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. American Folklife Center. REPORT NO ISBN-0-8444-0521-3 PUB DATE 94 NOTE 172p.; For the first edition, see ED 285 813. AVAILABLE FROMSuperintendent of Documents, P.O. Box 371954, Pittsburgh, PA 15250-7954 ($11, include stock no. S/N 030-001-00152-1 or U.S. Government Printing Office, Superintendent of Documents, Mail Stop: SSOP, Washington, DC 20402-93280. PUB TYPE Reference Materials Directories/Catalogs (132) EDRS PRICE MFOI/PC07 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Archives; *College Programs; Cultural Education; Cultural Maintenance; Elementary Secondary Education; *Folk Culture; Foreign Countries; Higher Education; Library Collections; *Organizations (Groups); *Primary Sources; Private Agencies; Public Agencies; *Publications; Rural Education IDENTIFIERS Ethnomusicology; *Folklorists; Folk Music ABSTRACT This directory lists professional folklore networks and other resources involved in folklife programming in the arts and social sciences, public programs, and educational institutions. The directory covers:(1) federal agencies; (2) folklife programming in public agencies and organizations, by state; (3)a listing by state of archives and special collections of folklore, folklife, and ethnomusicology, including date of establishment, access, research facilities, services, -

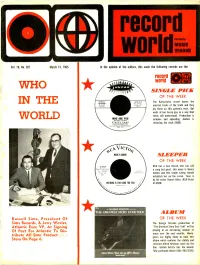

In Theopinion of Theeditors, This Week the Following Records Are The

record Formerly MUSIC worldVENDOR Vol. 19, No. 927 March 13, 1965 In theopinion of theeditors, this week the following records are the recordroll/1 world J F1,4 WHO SINGLE PICK OF THE WEEK RECORDNO. VOCAL Will. The Kama -Sutracrowdknowsthe 45-5500 iRST ACCOMP IN THE rill 12147) MAGGIE MUSS. TIME 2.06 (OW) musical tricks of the trade and they ply them on this galvanic rock.Gal wails at her bossy guy in a way that teens will understand.Production is WHO ARE YOU complexandappealing.Jubileeis WORLD (Chi Taylor-Ted Oaryll) STACEY CANE By GARY SHERMAN releasing the deck (5500). KAMA-SUTRA PRODUCTIONS pr HY MIIRAHI-PHI( STFINPERc ARTIE RIP,' NVICro#e NANCY ADAMS SLEEPER OF THE WEEK 47-8529 RCA has a new thrush who can sell Omer Productions, a song but good. Her name is Nancy Inc.,ASCAP SPHIA-1938 Adams and this single outing should 2:31 establish her on the scene. Tune is by hit writer Robert Allen. (RCA Victor NOTHING IS TOO GOOD FOR YOU 47.8529) Slew, GEORGE STEVENS THE GREATEST STORY EVER TOLD ALBUM Russell Sims, President Of OF THE WEEK Sims Records, & Jerry Wexler, TheGeorgeStevensproductionof Atlantic Exec VP, At Signing "The Greatest Story Ever Told" will be Of Pact For Atlantic To Dis- playinginan increasing number of areas over the next months.Movie- ... tribute All Sims Product. goers are highly likely to want this Story On Page 6. album which contains the stately and reverant Alfred Newman score for the film.United Artists has the beauti- fully packaged album (UAL/JAS 5120). -

Unit Theory of Knowledge 1 UNIT: HISTORY IS a SHAPE

History is A Shape: History Unit Theory of Knowledge 1 UNIT: HISTORY IS A SHAPE Created by Amy Scott: Coral Reef High School Overall Unit Question: Does history move in a circle, an upwards progression, a downwards spiral, or a straight line? 1.Topic: History—in particular an examination of historical progress as it relates to time period and social setting. This unit will follow a discussion of “How to Think About Progress,” chapter 46 of Mortimer Adler’s The Great Ideas. The students will debate philosophically whether or not human societies experience real change, either physically or morally. Additionally moving from the world perspective to a specific American historical era, the student will project themselves back in time to “virtually” experience the economic and physical hazards of homesteading in the 1880’s. Through a series of pre-and-post film activities (based on the PBS film Frontier House) the student will consider whether or not “progress” necessarily leads to the overall betterment of men and their societies. Ultimately by looking at the merits and demerits of modern life compared to prairie life they will answer (at least for this time period) whether history moves upwards, circularly, downwards, or on a straight line. 2. Goals and Objectives: The student will learn how to think about progress as a concept of history. He will become familiar with the contrasting ideologies of Aristotle, Hegel, Kant, Marx, Spencer, Kant, and Toynbee. The student will also consider what conditions are indispensable to progress and try to clarify and isolate a specific definition of progress beyond the material realm.