Datareport9.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

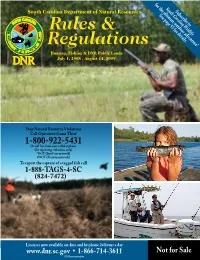

Rules & Regulations

for the ultimate outdoor adventure! South Carolina Wildlife South Carolina Department of Natural Resources Subscribe to Rules & See page 55 for details. Regulations Hunting, Fishing & DNR Public Lands July 1, 2008 - August 14, 2009 Stop Natural Resource Violations Call Operation Game Thief 1-800-922-5431Or call free from your cellular phone (for reporting violations only) *OGT (SunCom network) #OGT (Verizon network) To report the capture of a tagged fish call 1-888-TAGS-4-SC (824-7472) Licenses now available on-line and by phone 24 hours a day Not for Sale www.dnr.sc.gov$3.00 processing • 1-866-714-3611 fee Published July 1, 2008 Changes in Laws and Regulations This brochure is printed after the end of the legislative session, but prior to some late Table of Contents legislation or regulation changes and is provided for information only. Changes will be What’s New for 2008-2009 ..........7 publicized in local newspapers and on the DNR web site at www.dnr.sc.gov/regs/changes.html as any Education Programs ......................8 new legislation is passed. Discrepancies between the brochure and any statute or regulation shall be Invasive Aquatic Plants & Animals .....................................10 governed by the statute or regulation. Errors occasionally appear in this bro chure and news releases are Hunting and Fishing License published to clarify these situations. To research laws, visit www.scstatehouse.net/code/statmast.htm. Information ..............................11 Other information is published only in DNR news releases. This includes announce ments relative License Fees .............................12 to shrimp baiting, public hearings, fishing rodeos, DNR Board decisions and position statements, new Point & Suspension Systems ......13 legislation, youth activities, mobility impaired hunts, US Dept. -

CAPE ROMAIN NATIONAL WILDLIFE REFUGE Charleston County, South Carolina

COMPREHENSIVE CONSERVATION PLAN CAPE ROMAIN NATIONAL WILDLIFE REFUGE Charleston County, South Carolina U.S. Department of the Interior Fish and Wildlife Service Southeast Region Atlanta, Georgia July 2010 TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ...................................................................................................................... V I. BACKGROUND ................................................................................................................................. 1 Introduction ................................................................................................................................... 1 Purpose And Need For The Plan ................................................................................................. 1 u.s. Fish and Wildlife Service ....................................................................................................... 1 National Wildlife Refuge System .................................................................................................. 2 Legal and Policy Context .............................................................................................................. 4 National and International Conservation Plans and Initiatives ..................................................... 5 Relationship To State Wildlife Agency ..........................................................................................6 Climate Change ........................................................................................................................... -

Title to Conduct a Chemical Survey of the Water Quality at Borwick Fishery to Justify the Potential Impact Mass Baiting May Have on Fish Welfare

Dissertation Title To conduct a chemical survey of the water quality at Borwick Fishery to justify the potential impact mass baiting may have on fish welfare. Author Friend, Mike URL http://clok.uclan.ac.uk/9004/ Date Citation Friend, Mike To conduct a chemical survey of the water quality at Borwick Fishery to justify the potential impact mass baiting may have on fish welfare. [Dissertation] This document is made available to authorised users, that is current staff and students of the University of Central Lancashire only, to support teaching and learning at that institution under a https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/ licence. It may be shared with other authorised users in electronically or printed out and shared in that format. This cover sheet must be included with the whole document or with any parts shared. This document should not be published or disseminated via the internet, or in an analogue format beyond the network or community of the University of Central Lancashire. So, you may post it on the intranet or on the Blackboard VLE, but not on the openly accessible web pages. You may print it, or parts of it, and you may hand it to a class or individual as long as they are staff or students of the University of Central Lancashire. This does not affect any use under the current Copyright Law and permission may be asked via [email protected] for uses otherwise prescribed. To conduct a chemical survey of the water quality at Borwick Fishery to justify the potential impact mass baiting may have on fish welfare. -

Board Meeting Agenda and Materials and Monthly Division Reports

South Carolina Department of Natural Resources Board Meeting Agenda and Materials and Monthly Division Reports Board Meeting Scheduled for Videoconference https://scdnr2.webex.com/scdnr2/j.php?MTID=mb786d66feafef8aa7e4e0a0438488318 Meeting number (access code): 132 319 2411 Telephone: 1-844-992-4726 Access Code: 132 319 2411## March 18, 2021 10:00 AM Quick Tips and Logistics WebEx Video Conferencing Quick Tips Once you are logged into the WebEx meeting room this is the first screen you will see. Select “Start Meeting” Select “Mute” to eliminate all background noise. To see all the members in attendance you can select “Participants”. Select “chat” so that the host is always able to communicate with you. In the event of technical issues, the host will call you directly to assist you further. Agenda AGENDA SC DEPARTMENT OF NATURAL RESOURCES BOARD Virtual Meeting March 18, 2021 10:00 AM https://scdnr2.webex.com/scdnr2/j.php?MTID=mb786d66feafef8aa7e4e0a0438488318 Meeting number (access code): 132 319 2411 Telephone: 1-844-992-4726 Access Code: 132 319 2411## I. Call to Order ............................................................. Norman Pulliam, Chairman, SC DNR Board II. Videoconference Guidelines .............................................................. Valerie Shannon, Facilitator III. Invocation IV. Pledge of Allegiance............................................ Mike Hutchins, Vice Chairman, SC DNR Board V. Chairman’s Comments VI. Introduction of Guests ............ Emily Cope, Deputy Director for Wildlife and Freshwater Fisheries VII. Constituent Comments (Comments are limited to 5 minutes) ..................................... Emily Cope VIII. Approval of Minutes from February 18, 2021 meeting IX. Presentations/Commendations X. Advisory Committee Reports A. Governor’s Cup Billfishing Series ........................ Carlisle Oxner, DNR Board Representative B. Wildlife and Freshwater Fisheries .................................................... Mike Hutchins, Chairman XI. -

Economic Analysis of the 1991 South Carolina Shrimp Baiting Fishery

ECONOMIC ANALYSIS OF THE 1991 SOUTH CAROLINA SHRIMP BAITING FISHERY by David s. Liao Technical Report No. 81 South Carolina Marine Resources Center April, 1993 Economic Analysis and Seafood Marketing Program Off ice of Fisheries Management Marine Resources Division PO Box 12559 South Carolina Wildlife and Marine Resources Department Charleston, South Carolina 29422-2559 The views expressed in this report do not necessarily reflect those of the South Carolina Wildlife and Marine Resources Department. Any commercial product or trade name mentioned herein is not to be construed as an endorsement. TABLE OP CONTENTS Page I. INTRODUCTION Background and objectives of the Study• . .••..•.•• . 1 Research Methods. • • • . • . • • • • • . • • • • • . 1 II. CHAAACTERISTICS OP RECREATIONAL SHRIMPERS Demographi c Characteristics ••••.•••... ••.••..••..• 2 Trip Characte.rlstics. 3 III. FACTORS AFFECTING RECREATIONAL SHRIMPING TRIPS Estimation of Shrimping Trips ...••••••.. .•.•••••. 4 Estilllation of Recreational Shriaping Model ••.•..••. 4 IV. ECONOMIC VALUE OF THE SHRIMP BAITING FISHERY Estimation of Gross Economic Value • . .. •••••.•• . ... 5 Estimation of Net Economic Value ....... ...... .. 6 Co•parisona of Economic Values and Harvests between co11mercial and Recreational shrimping ..... 6 V. SUllMARY AND CONCLUSIONS Research Findings & Implications ••.•........•• . .... 7 Limitation• and Needed Further Reeearch . .. ...... 8 VI • RE.PERENCES . • . • . • • . • . • • . • . • . • . • • . • . • • • . • • 9 The South Carol ina Wildlife and Marine Resources Department prohibit• discrimination on the basis of race, C·ol or, sex, national origin, handicap or age. Direct all inquiriea to the Office of Personnel, P.O. Box 167, Columbia, SC 29202. ii List of Text Tables Table Paqe 1. Distri.but.ion of Permit HOlders .and Responsies in the Ma.11 survey by Area of Residence.. .. .. • .. .. .. .. .. • • .. .. • . .. .. • . .. 10 .2. Average Characte:ri.st.i.cs of Recreational Shrimpers by Ar,ea of R.es iclenc.e. -

Deepwater Shrimp Trapping in the Hawaiian Islands

MFR PAPER 1095 Paul Struhsa ker and Donald C. Aasted are on the staff of the Southwest Fis heries Cen te r, National Marine Fisheries Deepwater Shri mp Trapping in Service, NOAA, Honolulu, HI the Hawaiian Islands 96812. moderate numbers with th e trawls PAUL STRUHSAKER and DONALD C. AASTED between 150 and 400 fathoms (275 and 730 m). However. the initial in ABSTRACT-The results of preliminary deepwater shrimp trapping sur vestigations indicated that trappi ng. veys in the Ha waiian Islands consisting of 82 sets involving totals of 306 rather than trawling. was perhaps a traps and 3,960 h of fishing time in the 75 to 450-fathom ( 135-825 m) more effecti ve method for capturing depth range are discussed. A variety of traps, bait containers, and baits th ese latter species. were tested. Attempts to capture the penaeid shrimp, Penaeus marginatus, larke (1972) conducted trappIng in substantial numbers were unsuccessful. More success was experienced urveys during 1969 and 1970 at sev in trapping the caridean shrimps Heterocarpus ensifer and H. laevigatus. era l locales off the Hawaiian island of For these species, it was found that traps covered with burlap cloth out Oahu. The sampling gear consi ted of fished uncovered traps by factors of 2.5 to 10. H. ensifer was found to be everal trap type . but all were un most abundant in depths of 200-250 fathoms (365-455 m) where catches covered traps constructed of 0.5-inch with optimum trap and bait combinations ranged from 15 to 63 pounds (6.8 ( 13-mm) mesh wire screens. -

Final Restoration Plan and Environmental Assessment for Recreational Uses

Final Restoration Plan and Environmental Assessment for Recreational Uses 2002 M/V EVERREACH Oil Spill, Charleston South Carolina Prepared By: South Carolina Department of Natural Resources South Carolina Department of Health and Environmental Control National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration United States Fish and Wildlife Service, acting on behalf of the United States Department of the Interior Table of Contents 1. Introduction .............................................................................................................................................. 4 1.1 Background of Incident ....................................................................................................................... 4 1.2 Settlement, Ecological Restoration, and Recreational Use Damages ................................................. 4 1.3 Relationship between 2012 RP/EA and 2019 Draft RP/EA ................................................................. 4 1.4 Purpose and Need ............................................................................................................................... 4 1.5 Proposed Actions ................................................................................................................................ 5 1.6 Natural Resource Injuries Associated with the Site ............................................................................ 5 1.7 Trustees .............................................................................................................................................. -

Natural Resources, Department Of

AGENCY NAME: Department of Natural Resources AGENCY CODE: P240 SECTION: 47 Fiscal Year 2018–2019 Accountability Report SUBMISSION FORM SCDNR’s mission is to serve as the principal advocate for, and steward of, South AGENCY MISSION Carolina’s natural resources. SCDNR's vision is to be the trusted and respected leader in natural resources AGENCY VISION protection and management, by consistently making wise and balanced decisions for the benefit of the state's natural resources and its people. Does the agency have any major or minor recommendations (internal or external) that would allow the agency to operate more effectively and efficiently? Yes No RESTRUCTURING RECOMMENDATIONS: ☐ ☒ Is the agency in compliance with S.C. Code Ann. § 2-1-230, which requires submission of certain reports to the Legislative Services Agency for publication online and the State Library? See also S.C. Code Ann. § 60-2-30. Yes No REPORT SUBMISSION COMPLIANCE: ☒ ☐ A-1 AGENCY NAME: Department of Natural Resources AGENCY CODE: P240 SECTION: 47 Is the agency in compliance with various requirements to transfer its records, including electronic ones, to the Department of Archives and History? See the Public Records Act (S.C. Code Ann. § 30-1-10 through 30-1-180) and the South Carolina Uniform Electronic Transactions Act (S.C. Code Ann. § 26-6-10 through 26-10-210). Yes No RECORDS MANAGEMENT ☒ ☐ COMPLIANCE: Is the agency in compliance with S.C. Code Ann. § 1-23-120(J), which requires an agency to conduct a formal review of its regulations every five years? Yes No REGULATION REVIEW: ☒ ☐ Please identify your agency’s preferred contacts for this year’s accountability report. -

641 Subpart B—Refuge-Specific Regu- Lations For

U.S. Fish and Wildlife Serv., Interior § 32.20 Proclamations and or- ders Land and waters within boundary and adjacent to, State or in the vicinity ofÐ Citation No. Date Nov. 3, 1970 .. .......do ............ Eufaula Wildlife Refuge ............................................ 35 FR 16935. Nov. 3, 1970 .. .......do ............ Wassaw National Wildlife Refuge ............................ 35 FR 16936. 2748 Oct. 1, 1947 ... Illinois ............. Honshoe Lake, Alexander County ........................... 3 CFR, 1947 Supp. 12 FR 6521. Sept. 9, 1953 .......do ............ .......do ...................................................................... 18 FR 5495. 2748 Oct. 2, 1958 ... Iowa ............... Upper Mississippi River Wild Life and Fish Refuge 3 CFR, 1958 Supp.; 23 FR 7825. 2322 Feb. 7, 1939 .. Louisiana ....... Lacassine National Wildlife Refuge ......................... 3 CFR, Cum. Suppl. 4 FR 611. Nov. 19, 1982 .......do ............ Delta National Wildlife Refuge ................................. 47 FR 52183. Dec. 2, 1969 .. .......do ............ Lacassine National Wildlife Refuge ......................... 34 FR 19077. Aug. 13, 1960 Maryland ........ Martin National Wildlife Refuge ............................... 25 FR 7741. 2617 Oct. 18, 1948 Massachusetts Parker River National Wildlife Refuge ..................... 3 CFR, 1948 Supp. 13 FR 6115. Oct. 2, 1958 ... Minnesota ...... Upper Mississippi River Wild Life and Fish Refuge 3 CFR, 1958 Supp. 23 FR 7825. 2200 Oct. 7, 1936 ... Montana ......... Red Rock Lakes National Wildlife -

How to Catch Coarse Fish the LIBRARY of the UNIVERSITY of CALIFORNIA LOS ANGELES OW to CATCH OARSE FISH ROACH PERCH BREAM DACE CHUB and CARP

f^^sW Matthews How to catch coarse fish THE LIBRARY OF THE UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA LOS ANGELES OW TO CATCH OARSE FISH ROACH PERCH BREAM DACE CHUB AND CARP A 1-lNE CliUi; ONE OF THE "COUNTRY LIFE" BOOKLETS pp One Shilling Net "Tackle that is worth Fishing with." New SlK,rl~t,jn. Nr. Uakrli.1,1, Seijlcinbtr 22, 1920. Dear Siks, — I caught a two pounds ten ounces Bream with your 6x f lut on one of your light Split Cane Fly Rods a week or two ago. —Yours faithfully, R \V. S. Long Eaton, August 8, 1920. Dkar Sirs, — I am pleased to inform you I was in the Prize List last Saturday in Match with thirty picked men, L.K. and District Federation, N'our Match Tackle did it. I think 1 am right in saying the majority of Prize winners were using your T.ickle. —Yours tnily, J. A. Maidstone, July 27, 1920. Dear .Sir, —You will he interested to hear that I got a Bream, three pounds two ounces, on one of your Hair Hooks and 5S2 No. 9 Line last week. I hardly e.\pected to get him into the net but finally managed it. — Yours faithfully, F. C. No. 8 Catalogue, price SIXPENCE credited off FIRST ORDER of Ten ShiHings by COUPON. ALBERT SMITH & GO. (.Albert S.mith, Proprietor) (M.G.), Dominion Works, Redditch, Eng. DIRECT ONLY. NO AGENTS. J. PEEK & SON, WHOLESALE, RETAIL, AND EXPORT Fishing Rod and Tackle Manufacturers, 40, GRAY'S INN RD. {doseto HoWom^, LONDON, W.C. Best Greenheart Bottom Rods, 2 tops, division bag, rubber button .. -

Coarse Fishing for Beginners a Beginner's Guide to the Sport of Coarse Fishing Covering Tackle, Techniques and Bait

Coarse Fishing For Beginners A beginner's guide to the sport of Coarse Fishing covering tackle, techniques and bait. Brought to You By CoarseFishingGuide.co.uk Coarse Fishing For Beginners Legal Notices and Disclaimers Copyright Notice This ebook is Copyright © The Coarse Fishing Guide General Disclaimer The Publisher has strived to be as accurate and complete as possible in the creation of this ebook, notwithstanding the fact that he does not warrant or represent at any time that the contents within are accurate due to the rapidly changing nature of information. The Publisher will not be responsible for any losses or damages of any kind incurred by the reader whether directly or indirectly arising from the use of the information found in this ebook. No guarantees of any kind are made. Reader assumes responsibility for use of the information contained herein. The Publisher reserves the right to make changes without notice. The Publisher assumes no responsibility or liability whatsoever on the behalf of the reader of this report. Distribution Rights The Publisher grants you the right to sell or give away this ebook provided it is not altered in any way. Return to TOC Copyright © CoarseFishingGuide.co.uk Page 2 / 84 Coarse Fishing For Beginners Table of Contents Introduction ______________________________________________________________ 4 Chapter 1: About Coarse Fishing _______________________________________________ 5 Chapter 2: Licences and Permissions ____________________________________________ 6 Chapter 3: Fishing Tackle ____________________________________________________ -

1-888-Tags-4-Sc 1-866-714-3611

for the ultimate outdoor adventure! South Carolina Wildlife South Carolina Subscribe to RRulesules && See page 55 for details. RRegulationsegulations for Hunting, Fishing & Wildlife Management Areas July 1, 2007 - August 14, 2008 Stop Natural Resource Violations Call Operation Game Thief 1-800-922-5431Or call free from your cellular phone (for reporting violations only) *OGT (SunCom network) #OGT (Verizon network) To report the capture of a tagged fish call 1-888-TAGS-4-SC Visit DNR at www.dnr.sc.gov Licenses now available on-line and by phone and 24 hours a day 1-866-714-3611$3.00 processing fee Not for Sale Published July 1, 007 Changes in Laws and Regulations Table of Contents This brochure is printed after the end of the legislative session, but prior to some late What’s New for 007-008 ..........7 legislation or regulation changes and is provided for information only. Changes will be publicized Law Enforcement Education in local newspapers and on the DNR web site at www.dnr.sc.gov as any new legislation is passed. Programs .....................................8 Discrepancies between the brochure and any statute or regulation shall be governed by the statute Education Programs .....................9 Invasive Aquatic Plants & or regulation. Also, errors sometimes appear in this brochure, and news releases are published to Animals .....................................10 clarify these situations. To research laws visit www.scstatehouse.net/code/statmast.htm. Hunting and Fishing License Other information is published only in DNR news releases. This includes announcements relative Information ..............................11 to shrimp baiting, public hearings, fishing rodeos, DNR Board decisions and position statements, new License Fees .............................1 legislation, youth activities, mobility impaired hunts, US Dept.