Phillip Lopate Washington Heights

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

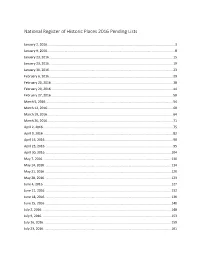

National Register of Historic Places Pending Lists for 2016

National Register of Historic Places 2016 Pending Lists January 2, 2016. ............................................................................................................................................ 3 January 9, 2016. ............................................................................................................................................ 8 January 23, 2016. ........................................................................................................................................ 15 January 23, 2016. ........................................................................................................................................ 19 January 30, 2016. ........................................................................................................................................ 23 February 6, 2016. ........................................................................................................................................ 29 February 20, 2016. ...................................................................................................................................... 38 February 20, 2016. ...................................................................................................................................... 44 February 27, 2016. ...................................................................................................................................... 50 March 5, 2016. ........................................................................................................................................... -

Study Guide August 13-16 2020

Study Guide August 13-16 2020 1 Dramaturg’s Note by Shannon Montague I am an educator. My entire life has been focused on the premise that curiosity is a gift with never-ending benefits. The more we seek to understand, the better. When I set out to create a packet of key terms for the cast of In the Heights, I didn’t think it would become the show’s official Study Guide, and that I would become the show’s dramaturg. I simply wanted to illuminate the world that Lin-Manuel Miranda created, complete with characters who are multi-layered and a world that spans generations. I not only sought to share what I knew, but also, more importantly, to understand what I didn’t know. I lived in the same time as Big Pun. I made mixtapes. Our cast did not. Miranda understands Latinx culture and growing up in New York City. I do not. What we all understand is that musical theater and the arts have power. That’s why we are here. I simply sought to fill the gaps. There are moments in this show that resonate across generations. The character Sonny in his solo rap during the song “96,000” says: “What about immigration?/ Politicians be hatin’./ Racism in this nation’s gone from latent to blatant./ I’ll cash my ticket and picket, invest in protest,/ never lost my focus till the city takes notice/ and you know this man! I’ll never sleep/ because the ghetto has a million promises/ for me to keep!” Whether you were alive in 1999 when Miranda was writing his earliest draft of the show or in 1943 when Abuela Claudia arrived in New York or you just know today, seven years since #BlackLivesMatter was founded, what we all see is the continued struggle for BIPOC to be seen, heard and known in America. -

2018 AIA Fellowship

This cover section is produced by the AIA Archives to show information from the online submission form. It is not part of the pdf submission upload. 2018 AIA Fellowship Nominee Pamela Jerome Organization Architectural Preservation Studio, DPC Location New York, NY Chapter AIA New York State; AIA New York Chapter Category of Nomination Category One - Preservation Summary Statement Pamela Jerome is an innovative leader in application of theory and doctrine on the preservation of significant structures in the US and worldwide. Her award-winning projects, volunteer work , publications, and training have international impact. Education M Sc Historic Preservation, Columbia University, New York, NY, 1989-1991 ; B Arch, Architectural Engineering, National Technical University, Athens, Greece, 1974-1979 Licensed in: New York, New Jersey, Connecticut, Rhode Island, Massachusetts, Greece Employment Architectural Preservation Studio, DPC, 2015-present (2.5 years); Wank Adams Slavin Associate LLP (WASA), 1986-2015 (29 years); Consulting for Architect, 1984-1986 (2 years); Stinchomb and Monroe, 1982-1984 (2 years); WYS Design, 1981-1982 (1 year) October 5, 2017 Karen Nichols, FAIA, Chair, 2018 Jury of Fellows The American Institute of Architects, 1735 New York Avenue, NW Washington, DC 20006-5292 Re: Pamela Jerome, AIA – Sponsorship for Elevation to Fellowship Dear Ms. Nichols: As a preservation and sustainability architect, the Past President of the Association for Preservation Technology International (APT) and the President of the Buffalo Architecture Center, it is my privilege to sponsor Pamela Jerome, the President of Architectural Preservation Studio, for nomination as a Fellow in the American Institute of Architects. Pamela and I are both graduates of the Master of Science in Historic Preservation program at Columbia University. -

Document.Pdf

Besen & Associates Investment Sales Team Hilly Soleiman Director (646) 424-5078 [email protected] Ronald H. Cohen Chief Sales Officer (212) 424-5317 [email protected] Paul J. Nigido Senior Financial Analyst (646) 424-5350 [email protected] Jared Rehberg Marketing Manager (646) 424-5067 [email protected] Table of Contents Executive Summary 4 Investment Highlights Property Overview 9 Location Map Property Photos Financial Overview 13 Income/Expense Report Commercial Rent Roll Property Diligence 26 Certificate of Occupancy Location Overview 28 Transportation Maps Zoning Overview 31 Executive Summary EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Besen & Associates, Inc., as exclusive agent for ownership, is pleased to offer for sale 4468-4474 Broadway, New York, NY 10040 (the “Property”), an elevatored, 2-story commercial building consisting of 6 stores and 5 offices. Built in 1991, the Property contains 20,000± SF and features 100’ of prime retail frontage along Broadway. 4468-4474 Broadway is situated on the east side of Broadway between Fairview Avenue and 192nd Street and is 4468-4474 Broadway located in one of the most desirable sections of Washington Heights in Northern Manhattan, boasting high foot traffic and bustling retail. The stores are currently renting at well-below market rates, offering tremendous upside to new ownership, and the Property contains 14,400± SF of unused air rights (TDR’s) for future redevelopment or value-add potential. The Property is located just north of the George Washington Bridge between Fort Tyron Park and Harlem River Park. Commuters are well served by public transportation, including the 190th Street subway station [“A”] and the 191st Street subway station [“1”]. -

Manhattan Borough President's Office FY 2020 Schools Capital Grant Awards- Sorted by Community Board

Manhattan Borough President's Office FY 2020 Schools Capital Grant Awards- Sorted by Community Board School Name School Number Project Title Project Address CB CD FY 20 Award 55 Battery Place Battery Park City School 02M276 Technology Upgrade 1 1 $75,000 New York, NY 10280 Lower Manhattan Arts 350 Grand Street 02M308 Technology Upgrade 1 1 $75,000 Academy New York, NY 10002 75 Broad Street Millennium High School 02M418 Classroom Projectors 1 1 $75,000 New York, NY 10004 201 Warren Street Public School 89 02M089 Technology Upgrade Room 208 1 1 $80,000 New York, NY 10282 55 Battery Place Public School 94 75M094 Technology Upgrade 1 1 $75,000 New York, NY 10280 Richard R. Green High 7 Beaver Street 02M580 Technology Upgrade 1 1 $75,000 School of Teaching New York, NY 10004 345 Chambers Street Stuyvesant High School 02M475 Theater Lights 1 1 $75,000 New York, NY 10282 University Neighborhood 200 Monroe Street 01M448 Bathroom Upgrade 1 1 $50,000 High School New York, NY 10002 10 South St Urban Assembly New 02M551 Electrical Upgrade Slip 7 1 1 $52,000 York Harbor School New York, NY 10004 131 Avenue of the Americas Chelsea CTE 02M615 Technology Upgrade New York, NY 10013 2 3 $100,000 High School 16 Clarkson Street City-As-School 02M560 Technology Upgrade 2 3 $75,000 New York, NY 10014 2 Astor Place Harvey Milk High School 02M586 Technology Upgrade 3rd Floor 2 2 $100,000 New York, NY 10003 High School of Hospitality 525 West 50th Street 02M296 Technology Upgrade 2 3 $75,000 Management New York, NY 10019 75 Morton Street Middle School 297 02M297 Hydroponics Lab 2 3 $50,000 New York, NY 10014 411 Pearl Street Murray Bergtraum 02M282 Water Fountains Room 436 2 1 $150,000 Campus New York, NY 10038 NYC Lab School for 333 West 17th Street 02M412 Technology Upgrade 2 3 $150,000 Collaborative Studies New York, NY 10011 P.S. -

Primary Contest List For

PRIMARY CONTEST LIST Primary Election 2014 - 09/09/2014 Printed On: 8/19/2014 2:57:53PM BOARD OF ELECTIONS PRIMARY CONTEST LIST TENTATIVE IN THE CITY OF NEW YORK SUBJECT TO CHANGE PRINTED AS OF: Primary Election 2014 - 09/09/2014 8/19/2014 2:57:53PM New York - Democratic Party Name Address Democratic Party Nominations for the following offices and positions: Governor Lieutenant Governor State Senator Member of the Assembly Male State Committee Female State Committee Delegate to Judicial Convention Alternate Delegate to the Judicial Convention Page 2 of 10 BOARD OF ELECTIONS PRIMARY CONTEST LIST TENTATIVE IN THE CITY OF NEW YORK SUBJECT TO CHANGE PRINTED AS OF: Primary Election 2014 - 09/09/2014 8/19/2014 2:57:53PM New York - Democratic Party Name Address Governor - Citywide Zephyr R. Teachout 171 Washington Park 5 Brooklyn, NY 11205 Andrew M. Cuomo 4 Bittersweet Lane Mount Kisco, NY 10549 Randy A. Credico 311 Amsterdam Avenue New York, NY 10023 Lieutenant Governor - Citywide Kathy C. Hochul 405 Gull Landing Buffalo, NY 14202 Timothy Wu 420 West 25 Street 7G New York, NY 10001 State Senator - 28th Senatorial District Shota N. Baghaturia 1691 2 Avenue 4S New York, NY 10128 Liz Krueger 350 East 78 Street 5G New York, NY 10075 State Senator - 31st Senatorial District Adriano Espaillat 62 Park Terrace West A87 New York, NY 10034 Luis Tejada 157-10 Riverside Drive West 5N New York, NY 10032 Robert Jackson 499 Fort Washington Avenue New York, NY 10033 Member of the Assembly - 71st Assembly District Kelley S. Boyd 240 Cabrini Boulevard New York, NY 10033 Herman D. -

Air Rights Based on ACRIS - Personal Property Legals

Air Rights Based on ACRIS - Personal Property Legals DOCUMENT ID RECORD TYPE BOROUGH BLOCK LOT EASEMENT 2021083001082001 L 3 7273 25 N 2021083000792002 L 3 186 1261 N 2021082300229001 L 3 6099 13 N 2021083000981001 L 3 208 331 N 2021080201510004 L 3 8673 28 N 2021083000792002 L 3 186 1260 N 2021080900700003 L 3 3537 20 N 2021082300262001 L 3 236 124 N 2021081201217001 L 1 841 75 N 2021083100255001 L 4 5750 6 N 2021030201450001 L 2 5803 985 N 2021080401522001 L 2 2673 135 N 2021080901003001 L 4 3322 156 N 2021083000792002 L 3 186 1259 N 2021081201552001 L 1 1055 49 N 2021081800864008 L 1 886 28 N 2021081901566001 L 4 8374 56 N 2021082300052001 L 3 5158 14 N 2021081600042001 L 3 5712 57 N Page 1 of 717 09/24/2021 Air Rights Based on ACRIS - Personal Property Legals SUBTERRANEAN PARTIAL LOT AIR RIGHTS PROPERTY TYPE STREET NUMBER RIGHTS E N N SP 2930 P N N CR 561 E N N SP 9201 E N N SP 160 P N N D2 3013 P N N CR 561 E N N CR 136 E N N SP 130 P N N CR 46 N N N SP 166-72 E N N SP 4445 E N N RG 788 N N N SP 83-83 P N N CR 561 E N N SP 428 E N N AP N/A E N N SP 252-06 E N N SP 385 P N N CR 5919 Page 2 of 717 09/24/2021 Air Rights Based on ACRIS - Personal Property Legals STREET NAME UNIT GOOD THROUGH DATE WEST 5TH STREET 17E 08/31/2021 PACIFIC STREET 1102 08/31/2021 SHORE ROAD D502 08/31/2021 COLUMBIA HEIGHTS 3AH 08/31/2021 BRIGHTON 3 STREET 08/31/2021 PACIFIC STREET 1101 08/31/2021 SUTTER AVENUE 08/31/2021 HENRY STREET 4F 08/31/2021 WEST 40TH STREET 08/31/2021 17TH ROAD 3-156 08/31/2021 POST ROAD 8K 08/31/2021 EAST 169 STREET 08/31/2021 118TH -

HHH Collections Management Database V8.0

HENRY HUDSON PARKWAY HAER NY-334 Extending 11.2 miles from West 72nd Street to Bronx-Westchester NY-334 border New York New York County New York WRITTEN HISTORICAL AND DESCRIPTIVE DATA HISTORIC AMERICAN ENGINEERING RECORD National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior 1849 C Street NW Washington, DC 20240-0001 HISTORIC AMERICAN ENGINEERING RECORD HENRY HUDSON PARKWAY HAER No. NY-334 LOCATION: The Henry Hudson Parkway extends from West 72nd Street in New York City, New York, 11.2 miles north to the beginning of the Saw Mill River Parkway at Westchester County, New York. The parkway runs along the Hudson River and links Manhattan and Bronx counties in New York City to the Hudson River Valley. DATES OF CONSTRUCTION: 1934-37 DESIGNERS: Henry Hudson Parkway Authority under direction of Robert Moses (Emil H. Praeger, Chief Engineer; Clinton F. Loyd, Chief of Architectural Design); New York City Department of Parks (William H. Latham, Park Engineer); New York State Department of Public Works (Joseph J. Darcy, District Engineer); New York Central System (J.W. Pfau, Chief Engineer) PRESENT OWNERS: New York State Department of Transportation; New York City Department of Transportation; New York City Department of Parks and Recreation; Metropolitan Transit Authority; Amtrak; New York Port Authority PRESENT USE: The Henry Hudson Parkway is part of New York Route 9A and is a linear park and multi-modal scenic transportation corridor. Route 9A is restricted to non-commercial vehicles. Commuters use the parkway as a scenic and efficient alternative to the city’s expressways and local streets. Visitors use it as a gateway to Manhattan, while city residents use it to access the Hudson River Valley, located on either side of the Hudson River. -

Lewis Mumford – Sidewalk Critic

SIDEWALK CRITIC SIDEWALK CRITIC LEWIS MUMFORD’S WRITINGS ON NEW YORK EDITED BY Robert Wojtowicz PRINCETON ARCHITECTURAL PRESS • NEW YORK Published by Library of Congress Princeton Architectural Press Cataloging-in-Publication Data 37 East 7th Street Mumford, Lewis, 1895‒1990 New York, New York 10003 Sidewalk critic : Lewis Mumford’s 212.995.9620 writings on New York / Robert Wojtowicz, editor. For a free catalog of books, p. cm. call 1.800.722.6657. A selection of essays from the New Visit our web site at www.papress.com. Yorker, published between 1931 and 1940. ©1998 Princeton Architectural Press Includes bibliographical references All rights reserved and index. Printed and bound in the United States ISBN 1-56898-133-3 (alk. paper) 02 01 00 99 98 5 4 3 2 1 First edition 1. Architecture—New York (State) —New York. 2. Architecture, Modern “The Sky Line” is a trademark of the —20th century—New York (State)— New Yorker. New York. 3. New York (N.Y.)— Buildings, structures, etc. I. Wojtowicz, No part of this book my be used or repro- Robert. II. Title. duced in any manner without written NA735.N5M79 1998 permission from the publisher, except in 720’.9747’1—dc21 98-18843 the context of reviews. CIP Editing and design: Endsheets: Midtown Manhattan, Clare Jacobson 1937‒38. Photo by Alexander Alland. Copy editing and indexing: Frontispiece: Portrait of Lewis Mumford Andrew Rubenfeld by George Platt Lynes. Courtesy Estate of George Platt Lynes. Special thanks to: Eugenia Bell, Jane Photograph of the Museum of Modern Garvie, Caroline Green, Dieter Janssen, Art courtesy of the Museum of Modern Therese Kelly, Mark Lamster, Anne Art, New York. -

City-Owned Properties Based on Suitability of City-Owned and Leased Property for Urban Agriculture (LL 48 of 2011)

City-Owned Properties Based on Suitability of City-Owned and Leased Property for Urban Agriculture (LL 48 of 2011) Borou Block Lot Address Parcel Name gh 1 2 1 4 SOUTH STREET SI FERRY TERMINAL 1 2 2 10 SOUTH STREET BATTERY MARITIME BLDG 1 2 3 MARGINAL STREET MTA SUBSTATION 1 2 23 1 PIER 6 PIER 6 1 3 1 10 BATTERY PARK BATTERY PARK 1 3 2 PETER MINUIT PLAZA PETER MINUIT PLAZA/BATTERY PK 1 3 3 PETER MINUIT PLAZA PETER MINUIT PLAZA/BATTERY PK 1 6 1 24 SOUTH STREET VIETNAM VETERANS PLAZA 1 10 14 33 WHITEHALL STREET 1 12 28 WHITEHALL STREET BOWLING GREEN PARK 1 16 1 22 BATTERY PLACE PIER A / MARINE UNIT #1 1 16 3 401 SOUTH END AVENUE BATTERY PARK CITY STREETS 1 16 12 MARGINAL STREET BATTERY PARK CITY Page 1 of 1390 09/28/2021 City-Owned Properties Based on Suitability of City-Owned and Leased Property for Urban Agriculture (LL 48 of 2011) Agency Current Uses Number Structures DOT;DSBS FERRY TERMINAL;NO 2 USE;WATERFRONT PROPERTY DSBS IN USE-TENANTED;LONG-TERM 1 AGREEMENT;WATERFRONT PROPERTY DSBS NO USE-NON RES STRC;TRANSIT 1 SUBSTATION DSBS IN USE-TENANTED;FINAL COMMITMNT- 1 DISP;LONG-TERM AGREEMENT;NO USE;FINAL COMMITMNT-DISP PARKS PARK 6 PARKS PARK 3 PARKS PARK 3 PARKS PARK 0 SANIT OFFICE 1 PARKS PARK 0 DSBS FERRY TERMINAL;IN USE- 1 TENANTED;FINAL COMMITMNT- DISP;LONG-TERM AGREEMENT;NO USE;WATERFRONT PROPERTY DOT PARK;ROAD/HIGHWAY 10 PARKS IN USE-TENANTED;SHORT-TERM 0 Page 2 of 1390 09/28/2021 City-Owned Properties Based on Suitability of City-Owned and Leased Property for Urban Agriculture (LL 48 of 2011) Land Use Category Postcode Police Prct -

PRIMARY CONTEST LIST Primary Election 2021 - 06/22/2021

PRIMARY CONTEST LIST Primary Election 2021 - 06/22/2021 Printed On: 6/17/2021 4:24:00PM BOARD OF ELECTIONS PRIMARY CONTEST LIST TENTATIVE IN THE CITY OF NEW YORK SUBJECT TO CHANGE PRINTED AS OF: Primary Election 2021 - 06/22/2021 6/17/2021 4:24:00PM New York - Democratic Party Name Address Democratic Party Nominations for the following offices and positions: Mayor Public Advocate City Comptroller Borough President District Attorney Member of the City Council Judge of the Civil Court - District Female District Leader Female District Leader Male District Leader Delegate to Judicial Convention Alternate Delegate to the Judicial Convention Page 2 of 17 BOARD OF ELECTIONS PRIMARY CONTEST LIST TENTATIVE IN THE CITY OF NEW YORK SUBJECT TO CHANGE PRINTED AS OF: Primary Election 2021 - 06/22/2021 6/17/2021 4:24:00PM New York - Democratic Party Name Address Mayor - Citywide Aaron S. Foldenauer 90 Washington Street New York, NY 10006 Dianne Morales 200 Jefferson Avenue Brooklyn, NY 11216 Scott M. Stringer 25 Broad Street 12S New York, NY 10004 Raymond J. McGuire 145 Central Park West New York, NY 10023 Maya D. Wiley 1519 Albemarle Road Brooklyn, NY 11226 Paperboy Love Prince 852 Monroe Street 3 Brooklyn, NY 11221 Art Chang 384 Sterling Place Brooklyn, NY 11238 Kathryn A. Garcia 591 Carroll Street Brooklyn, NY 11215 Eric L. Adams 936 Lafayette Avenue FL 1 Brooklyn, NY 11221 Isaac Wright Jr. 785 Seneca Avenue Ridgewood, NY 11385 Shaun Donovan 139 Bond Street Brooklyn, NY 11217 Andrew Yang 650 West 42 Street New York, NY 10036 Joycelyn Taylor 153 Jefferson Avenue Brooklyn, NY 11216 Public Advocate - Citywide Anthony L. -

Table of Contents

COMMUNITY BOARD 12, Manhattan Resource Directory Preliminary Edition Eleazar Bueno Chairman Ebenezer Smith District Manager Community Board 12 530 West 166th St. Suite 6A New York, NY 10032 (212) 568-8500 www.nyc.gov/mcb12 Updated on: July 2019 Table of Contents Cultural Institutions & Places of Interest _________________________________________Page 4 Important Phone Numbers ___________________________________________________Page 5 Public Officials/Fire Houses/Police Precincts_____________________________________Page 6 Post Offices/Community Newspaper/Hospital and Clinics/ Health Services/Legal Services/Business Organizations/Homeless Housing Units________Page 7 Food Pantry Programs/Libraries/Senior Center Programs/Recreation Centers/ Public Elementary Schools_______________________________________________Pages 8 & 9 Public Intermediate & High Schools Parochial Schools _____________________________Page 9 College & Universities/ESL & Adult Classes________________________________Pages 10 & 11 Youth Services/ Child Care & Pre-School Community-Based-Organizations/ Neighborhood/Block Association _____________________________________________ Page 11 Faith Based Institutions__________________________________________________Page, 12, 13 3 IMPORTANT PHONE NUMBERS 311- New York City Services Hotline Rat Infestation Complaints..............................................…………..311 411- New York City Information Hotline Runaway Hotline ...........................................…...........1-800-786-2929 911- New York City Emergency Hotline Sanitation