Modernity. Progress and Decadentism

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Supplementary Information For

1 2 Supplementary Information for 3 Dissecting landscape art history with information theory 4 Byunghwee Lee, Min Kyung Seo, Daniel Kim, In-seob Shin, Maximilian Schich, Hawoong Jeong, Seung Kee Han 5 Hawoong Jeong 6 E-mail:[email protected] 7 Seung Kee Han 8 E-mail:[email protected] 9 This PDF file includes: 10 Supplementary text 11 Figs. S1 to S20 12 Tables S1 to S2 13 References for SI reference citations www.pnas.org/cgi/doi/10.1073/pnas.2011927117 Byunghwee Lee, Min Kyung Seo, Daniel Kim, In-seob Shin, Maximilian Schich, Hawoong Jeong, Seung Kee Han 1 of 28 14 Supporting Information Text 15 I. Datasets 16 A. Data curation. Digital scans of landscape paintings were collected from the two major online sources: Wiki Art (WA) (1) 17 and the Web Gallery of Art (WGA) (2). For our purpose, we collected 12,431 landscape paintings by 1,071 artists assigned to 18 61 nationalities from WA, and 3,610 landscape paintings by 816 artists assigned with 20 nationalities from WGA. While the 19 overall number of paintings from WGA is relatively smaller than from WA, the WGA dataset has a larger volume of paintings 20 produced before 1800 CE. Therefore, we utilize both datasets in a complementary way. 21 As same paintings can be included in both datasets, we carefully constructed a unified dataset by filtering out the duplicate 22 paintings from both datasets by using meta-information of paintings (title, painter, completion date, etc.) to construct a unified 23 set of painting images. The filtering process is as follows. -

Judit Nagy Cultural Encounters on the Canvas

JUDIT NAGY CULTURAL ENCOUNTERS ON THE CANVAS: EUROPEAN INFLUENCES ON CANADIAN LANDSCAPE PAINTING 1867–1890 Introduction Whereas the second half of the 19th century is known as the age of transition in Victorian England, the post-confederation decades of the same century can be termed the age of possibilities in Canadian landscape painting, both transition and possibilities referring to a stage of devel- opment which focuses on potentialities and entails cultural encounters. Fuelled both by Europe’s cultural imprint and the refreshing impressions of the new land, contemporary Canadian landscapists of backgrounds often revealing European ties tried their hands at a multiplicity and mixture of styles. No underlying homogenous Canadian movement of art supported their endeavour though certain tendencies are observable in the colourful cavalcade of works conceived during this period. After providing a general overview of the era in Canadian landscape painting, the current paper will discuss the oeuvre of two landscapists of the time, the English-trained Allan Edson, and the German immigrant painter Otto Reinhold Jacobi1 to illustrate the scope of the ongoing experimentation with colour and light and to demonstrate the extent of European influence on contemporary Canadian landscape art. 1 Members of the Canadian Society of Artists, both Edson and Jacobi were exceptional in the sense that, unlike many landscapists at Confederation, they traded in their European settings into genuine Canadian ones. In general, “artists exhibited more scenes of England and the Continent than of Ontario and Quebec.” (Harper 179) 133 An overview of the era in landscape painting Meaning to capture the spirit of the given period in Canadian history, W. -

Happy Valentine's 2020

Happy Valentine's 2020 Americans began exchanging Valentines in the 1700s. In the 1800s Esther Howland took it to a new level during the Civil War when Valentines were very popular. Families, friends and loved ones were separated and feared they would never see each other again. Esther Howland popularized and mass-produced Valentine’s Day cards like this one, using lace, ribbons and colorful paper. She had an all-women assembly line in Worcester, Massachusetts, which started in her bedroom in her family home and grew to have annual revenues of $100,000. (substantial at that time). This forgotten entrepreneur - Esther who? - was a classmate of Emily Dickinson at Mount Holyoke and named her booming business The New England Valentine Company. 1 of 23 People enjoyed sending tokens of affection, poems, pictures, locks of hair and simple homemade cards. Now they could purchase elaborate ones with hidden doors, gilded lace and artistic illustrations. The visionary Esther became known as "The Mother of the American Valentine." (Courtesy American Antiquarian Society) 2 of 23 I can't send you a three dimensional Valentine with accordion effects and a string which moves a bouquet of flowers to reveal a verse (Esther's innovation - still used today), but I am sending you some paintings evocative of the spirit of Valentine's Day. I am featuring American painters in our GDAS year of Americana. 3 of 23 Sundown at Yosemite , Alfred Bierstadt, 1863 Romantic souls love sunsets. A recent survey showed most adults feel a sunset puts them in a romantic mood, even more than dinner by candlelight. -

Canadian, Impressionist & Modern

CanAdiAn, impressionist & modern Art Sale Wednesday, december 2, 2020 · 4 pm pt | 7 pm et i Canadian, impressionist & modern art auCtion Wednesday, December 2, 2020 Heffel’s Digital Saleroom Post-War & Contemporary Art 2 PM Vancouver | 5 PM Toronto / Montreal Canadian, Impressionist & Modern Art 4 PM Vancouver | 7 PM Toronto / Montreal previews By appointment Heffel Gallery, Vancouver 2247 Granville Street Friday, October 30 through Wednesday, November 4, 11 am to 6 pm PT Galerie Heffel, Montreal 1840 rue Sherbrooke Ouest Monday, November 16 through Saturday, November 21, 11 am to 6 pm ET Heffel Gallery, Toronto 13 Hazelton Avenue Together with our Yorkville exhibition galleries Thursday, November 26 through Tuesday, December 1, 11 am to 6 pm ET Wednesday, December 2, 10 am to 3 pm ET Heffel Gallery Limited Heffel.com Departments Additionally herein referred to as “Heffel” Consignments or “Auction House” [email protected] appraisals CONTACt [email protected] Toll Free 1-888-818-6505 [email protected], www.heffel.com absentee, telephone & online bidding [email protected] toronto 13 Hazelton Avenue, Toronto, Ontario M5R 2E1 shipping Telephone 416-961-6505, Fax 416-961-4245 [email protected] ottawa subsCriptions 451 Daly Avenue, Ottawa, Ontario K1N 6H6 [email protected] Telephone 613-230-6505, Fax 613-230-6505 montreal Catalogue subsCriptions 1840 rue Sherbrooke Ouest, Montreal, Quebec H3H 1E4 Heffel Gallery Limited regularly publishes a variety of materials Telephone 514-939-6505, Fax 514-939-1100 beneficial to the art collector. An Annual Subscription entitles vanCouver you to receive our Auction Catalogues and Auction Result Sheets. 2247 Granville Street, Vancouver, British Columbia V6H 3G1 Our Annual Subscription Form can be found on page 103 of this Telephone 604-732-6505, Fax 604-732-4245 catalogue. -

Worthwhile Magazine Content Style Guide

WORTHWHILE MAGAZINE CONTENT STYLE GUIDE Table of Contents ABOUT WORTHWHILE MAGAZINE 4 ABBREVIATIONS 4 ACRONYMS 4 AMPERSANDS 4 CAPITALIZATION 4 AFTER A COLON 4 BOOK TITLES 5 STYLES AND PERIOD 5 JOB TITLES 5 FOREIGN TERMS 5 HEADINGS AND SUBHEADINGS 5 CONTRACTIONS 5 FONT AND TEXT STYLE 6 FORMATTING 6 IMAGE USE 6 BOOK LISTS 6 NUMBERS 7 DATES 7 ORDINAL NUMBERS 7 PERCENTAGES 7 PHONE NUMBERS 7 TIME 7 PUNCTUATION 8 APOSTROPHES 8 COMMAS 8 DASHES 8 ELLIPSES 8 HYPHENS 8 QUOTES 9 VOICE AND TONE 9 WORD CHOICE 9 Last updated: 8/17/2018 2 BETWEEN VS. AMONG 9 EFFECT VS. AFFECT 10 INSURE, ENSURE, AND ASSURE 10 WHICH VS. THAT 10 E.G. VS. I.E 10 OTHER NOTES 11 WORD LIST 11 ART MOVEMENTS, PERIODS, AND STYLES 16 PERIOD VERSUS STYLE 18 APPENDIX A: WHEN TO USE EM DASHES AND SEMICOLONS 18 APPENDIX B: UK VS. AMERICAN ENGLISH SPELLING 19 COLLECTIONS AND COLLECTORS/CREDIT LINES 19 Last updated: 8/17/2018 3 About Worthwhile Magazine Brief Description: Worthwhile Magazine is an online repository of personal property appraisal knowledge accessible to the general public and professionals alike. Discussions include evolving practices and current scholarship used when valuing the various fields of collecting. Since knowledge is power, we believe an open dialogue about connoisseurship is worthwhile. Abbreviations Avoid abbreviating any words that the audience won’t understand immediately. For common abbreviations, include a period. Ex: Capt. Smith wrote a memo for Mrs. Mayfair, reminding her to pick up a pound of apples at the store. We do not abbreviate circa or century so as to not confuse our audience. -

NINETEENTH CENTURY AMERICAN PAINTINGS at BOWDOIN COLLEGE Digitized by the Internet Archive

V NINETEENTH CENTURY^ AMERIGAN PAINTINGS AT BOWDOIN COLLEGE NINETEENTH CENTURY AMERICAN PAINTINGS AT BOWDOIN COLLEGE Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2015 https://archive.org/details/nineteenthcenturOObowd_0 NINETEENTH CENTURY AMERICAN PAINTINGS AT BOWDOIN COLLEGE BOWDOIN COLLEGE MUSEUM OF ART 1974 Copyright 1974 by The President and Trustees of Bowdoin College This Project is Supported by a Grant from The National Endowment for The Arts in Washington, D.C. A Federal Agency Catalogue Designed by David Berreth Printed by The Brunswick Publishing Co. Brunswick, Maine FOREWORD This catalogue and the exhibition Nineteenth Century American Paintings at Bowdoin College begin a new chapter in the development of the Bow- doin College Museum of Art. For many years, the Colonial and Federal portraits have hung in the Bowdoin Gallery as a permanent exhibition. It is now time to recognize that nineteenth century American art has come into its own. Thus, the Walker Gallery, named in honor of the donor of the Museum building in 1892, will house the permanent exhi- bition of nineteenth century American art; a fitting tribute to the Misses Walker, whose collection forms the basis of the nineteenth century works at the College. When renovations are complete, the Bowdoin and Boyd Galleries will be refurbished to house permanent installations similar to the Walker Gal- lery's. During the renovations, the nineteenth century collection will tour in various other museiniis before it takes its permanent home. My special thanks and congratulations go to David S. Berreth, who developed the original idea for the exhibition to its present conclusion. His talent for exhibition installation and ability to organize catalogue materials will be apparent to all. -

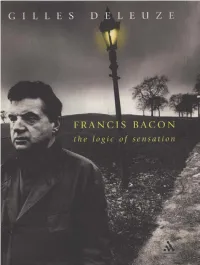

Francis Bacon: the Logic of Sensation

Francis Bacon: the logic of sensation GILLES DELEUZE Translated from the French by Daniel W. Smith continuum LONDON • NEW YORK This work is published with the support of the French Ministry of Culture Centre National du Livre. Liberte • Egalite • Fraternite REPUBLIQUE FRANCAISE This book is supported by the French Ministry for Foreign Affairs, as part of the Burgess programme headed for the French Embassy in London by the Institut Francais du Royaume-Uni. Continuum The Tower Building 370 Lexington Avenue 11 York Road New York, NY London, SE1 7NX 10017-6503 www.continuumbooks.com First published in France, 1981, by Editions de la Difference © Editions du Seuil, 2002, Francis Bacon: Logique de la Sensation This English translation © Continuum 2003 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical including photocopying, recording or any information storage or retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publishers. British Library Gataloguing-in-Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from The British Library ISBN 0-8264-6647-8 Typeset by BookEns Ltd., Royston, Herts. Printed by MPG Books Ltd., Bodmin, Cornwall Contents Translator's Preface, by Daniel W. Smith vii Preface to the French Edition, by Alain Badiou and Barbara Cassin viii Author's Foreword ix Author's Preface to the English Edition x 1. The Round Area, the Ring 1 The round area and its analogues Distinction between the Figure and the figurative The fact The question of "matters of fact" The three elements of painting: structure, Figure, and contour - Role of the fields 2. -

Link to Floral Art History by Exhibition Curator

Floral Art History First published as the Introduction of the catalogue documenting BLOSSOM ~ Art of Flowers II, sponsored by the Susan K. Black Foundation Flowers have been portrayed by artists for centuries if not from this epoch known as Vanitas contained imagery that was millennia. In the arch of western art history, there are a number of generally understood as allegory for various themes such as, beauty epochs, each of which comprise certain advances that demonstrate is fleeting and can fade, life is transient, etc. The Baroque artist how floral art has evolved. The following are some of the more Jacques de Gheyn II (1565–1629) is said to be the first to paint still significant highlights of floral art history. life and flower paintings in Holland, inspired by Carolus Clusius, a botanist who designed a botanical garden at the university in The Epoch of the Renaissance and Leiden. There is a long list of others who followed, the most the Rise of Botanical Illustration noteworthy of which include Jan Brueghel the Elder (1568–1625), This epoch includes: a.) pictorial traditions such as floral borders Ambrosius Bosschaert the Elder (1573–1621), Roelandt Savery and illumination in devotional manuscripts known as Books of (1576–1639), Osias Beert (1580–1624), Jan Davidsz. de Heem Hours (e.g., the Warburg Book of Hours, c. 1500); b.) naturalism (1606–1684), and Jan van Huysum (1682–1749). Brueghel’s sons of artists working in the manner of Albrecht Dürer (1471–1528) of Jan Brueghel the Younger (1601–1678) and Ambrosius Brueghel Nuremburg, Germany; c.) botanical woodcuts such as those of (1617–1675) also specialized in flowers. -

John Sloan and Stuart Davis Is Gloucester: 1915-1918

JOHN SLOAN AND STUART DAVIS IS GLOUCESTER: 1915-1918 A thesis submitted to the College of the Arts of Kent State University in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Master of Arts by Kelly M. Suredam May, 2013 Thesis written by Kelly M. Suredam B.A., Baldwin-Wallace College, 2009 M.A., Kent State University, 2013 Approved by _____________________________, Advisor Carol Salus _____________________________, Director, School of Art Christine Havice _____________________________, Dean, College of the Arts John R. Crawford ii TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF CONTENTS…………………………………………………………..………...iii LIST OF FIGURES…………………………………………………………….…………….iv ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS………………………………………………………………….xii INTRODUCTION…………………………………………………………………………….1 CHAPTER I. A BRIEF HISTORY OF GLOUCESTER……………………………………….....6 II. INFLUENCES: ROBERT HENRI, THE ASHCAN SCHOOL, AND THE MARATTA COLOR SYSTEM……………………………………………………..17 III. INFLUENCES: THE 1913 ARMORY SHOW………………………………….42 IV. JOHN SLOAN IN GLOUCESTER……………………………………………...54 V. STUART DAVIS IN GLOUCESTER……………………………………………76 VI. CONCLUSION: A LINEAGE OF AMERICAN PAINTERS IN GLOUCESTER………………………………………………………………………97 REFERENCES……………………………………………………………………………..112 FIGURES…………………………………………………………………………………...118 iii LIST OF FIGURES Figure Page 1. John Sloan, Near Sunset, Gloucester, 1914-1915………………..………..………..……118 2. Stuart Davis, Gloucester Environs, 1915……………………………………..………….118 3. Map of Gloucester, Massachusetts………………………………………….…...............119 4. Cape Ann Map…………………………………………………………………………...119 5. Map of the Rocky -

National Gallery of Art Postage and Fees Paid Washington, D.C

National Gallery of Art Postage and Fees Paid Washington, D.C. 20565 National Gallery of Art Official Business Third Class Bulk Rate Penalty for Private Use, $300 Return Postage Guaranteed CALENDAR OF EVENTS May 1980 Painting Sunday Sunday of the Week Tours Films Lectures Concerts MONDAY, Van der Weyden Small French Paintings The Secret World of The Renascence of 37th American April 28 Portrait of a Lady from the Bequest of Ailsa OdUon Redon (30 min.) Nineteenth-Century Music Festival (Andrew W. Mellon Mellon Brace and Other Tues. through Sat. 12:30 Italian Art Charles through Collection) National Gallery &6:00; Sun. 1:00 Fierro, Pianist Speaker: SUNDAY, Collections West Building Tues. through Sat. 12:00 East Building Roberta J. M. Olson Tues. through Sat. 1:00 East May 4 &2:00; Sun. 3:30 & 6:00 Auditorium Professor of Art History Garden Court 7:00 Sun. 2:30 Wheaton West Building East Building College Norton, Massachusetts Gallery 39 Ground Floor Lobby Introduction to the West Sunday 4:00 Building's Collection East Building Mon. through Sat. 11:00 Auditorium Sun. 1:00 West Building Rotunda Introduction to the East Building's Collection Mon. through Sat. 3:00 Sun. 5:00 East Building Ground Floor Lobby MONDAY, Johnson American Light: The Edgar Degas (26 min.) Composition vs. 37th American May 5 The Brown Family Luminist Movement Monet (6 min.) Decoration in Music Festival (Gift of David Edward 1850-1875 Tues. through Sat. 12:30 Nonobjective Art through Finley and Margaret Tues. through Sat. 1:00 &6:00; Sun. 1:00 Helen Boatwright, SUNDAY, Eustis Finley) Sun. -

READ ME FIRST Here Are Some Tips on How to Best Navigate, find and Read the Articles You Want in This Issue

READ ME FIRST Here are some tips on how to best navigate, find and read the articles you want in this issue. Down the side of your screen you will see thumbnails of all the pages in this issue. Click on any of the pages and you’ll see a full-size enlargement of the double page spread. Contents Page The Table of Contents has the links to the opening pages of all the articles in this issue. Click on any of the articles listed on the Contents Page and it will take you directly to the opening spread of that article. Click on the ‘down’ arrow on the bottom right of your screen to see all the following spreads. You can return to the Contents Page by clicking on the link at the bottom of the left hand page of each spread. Direct links to the websites you want All the websites mentioned in the magazine are linked. Roll over and click any website address and it will take you directly to the gallery’s website. Keep and fi le the issues on your desktop All the issue downloads are labeled with the issue number and current date. Once you have downloaded the issue you’ll be able to keep it and refer back to all the articles. Print out any article or Advertisement Print out any part of the magazine but only in low resolution. Subscriber Security We value your business and understand you have paid money to receive the virtual magazine as part of your subscription. Consequently only you can access the content of any issue. -

Collection of American Paintings Highlights From

Highlights_COVER 090816.crw1.indd All Pages 9/12/16 2:09 PM HIGHLIGHTS FROM COLLECTION OF AMERICAN PAINTINGS November 1, 2016–January 2, 2017 FOREWORD Richard Rossello, Principal Art galleries are seldom accused of understatement, and words like “sub- lime,” “luminous,” and “exquisite” are used so often that readers can’t be faulted for taking our descriptions with a large grain of salt. The fact is that collectors should and do make up their own minds about what is extraordinary and what is run-of-the-mill. Our effort to exhort interest is only so much noise at the end of the day. That said, we hope you can for- give our enthusiasm. We tend to fall in love with our paintings and feel a bit like dog breeders who want to see their beloved puppies go to good homes. Recently, my announcement that we had sold a newly acquired painting, one that happens to be included in this catalogue, was met with groans in the office rather than applause. “We haven’t had a chance to live with it yet!” was the complaint. We were collectors long before we were dealers, and when we established the gallery, we made a promise to ourselves that we would only buy works of art we would want to keep for our own collections. We have stayed true to that promise, looking at literally hundreds of paintings for every one we buy. We live for that wonderful moment when we see a picture that should be part of Avery Galleries. We’re proud to own them, and because of that, I hope you will forgive us if we get car- ried away with our descriptions.