Library Book Selection and the Public Schools: the Quest for the Archimedean Point

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Beyond Skepticism Foundationalism and the New Fuzziness: the Role of Wide Reflective Equilibrium in Legal Theory Robert Justin Lipkin

Cornell Law Review Volume 75 Article 2 Issue 4 May 1990 Beyond Skepticism Foundationalism and the New Fuzziness: The Role of Wide Reflective Equilibrium in Legal Theory Robert Justin Lipkin Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.law.cornell.edu/clr Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Robert Justin Lipkin, Beyond Skepticism Foundationalism and the New Fuzziness: The Role of Wide Reflective Equilibrium in Legal Theory , 75 Cornell L. Rev. 810 (1990) Available at: http://scholarship.law.cornell.edu/clr/vol75/iss4/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at Scholarship@Cornell Law: A Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Cornell Law Review by an authorized administrator of Scholarship@Cornell Law: A Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. BEYOND SKEPTICISM, FOUNDATIONALISM AND THE NEW FUZZINESS: THE ROLE OF WIDE REFLECTIVE EQUILIBRIUM IN LEGAL THEORY Robert Justin Liphint TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION .............................................. 812 I. FOUNDATIONALISM AND SKEPTICISM ..................... 816 A. The Problem of Skepticism ........................ 816 B. Skepticism and Nihilism ........................... 819 1. Theoretical and PracticalSkepticism ................ 820 2. Subjectivism and Relativism ....................... 821 3. Epistemic and Conceptual Skepticism ................ 821 4. Radical Skepticism ............................... 822 C. Modified Skepticism ............................... 824 II. NEW FOUNDATIONALISM -

Read PDF Tickle Time! (A Boynton on Board Book)

Tickle Time! (A Boynton on Board Book) by Sandra Boynton, Download PDF Tickle Time! (A Boynton on Board Book) Online, Read PDF Tickle Time! (A Boynton on Board Book), Full PDF Tickle Time! (A Boynton on Board Book), All Ebook Tickle Time! (A Boynton on Board Book), PDF and EPUB Tickle Time! (A Boynton on Board Book), PDF ePub Mobi Tickle Time! (A Boynton on Board Book), Reading PDF Tickle Time! (A Boynton on Board Book), Book PDF Tickle Time! (A Boynton on Board Book), Read online Tickle Time! (A Boynton on Board Book), Tickle Time! (A Boynton on Board Book) Sandra Boynton pdf, by Sandra Boynton Tickle Time! (A Boynton on Board Book), book pdf Tickle Time! (A Boynton on Board Book), by Sandra Boynton pdf Tickle Time! (A Boynton on Board Book), Sandra Boynton epub Tickle Time! (A Boynton on Board Book), pdf Sandra Boynton Tickle Time! (A Boynton on Board Book), the book Tickle Time! (A Boynton on Board Book), Sandra Boynton ebook Tickle Time! (A Boynton on Board Book), Tickle Time! (A Boynton on Board Book) E-Books, Online Tickle Time! (A Boynton on Board Book) Book, pdf Tickle Time! (A Boynton on Board Book), Tickle Time! (A Boynton on Board Book) E-Books, Tickle Time! (A Boynton on Board Book) Online Download Best Book Online Tickle Time! (A Boynton on Board Book), Read Online Tickle Time! (A Boynton on Board Book) Book, Download Online Tickle Time! (A Boynton on Board Book) E-Books, Download Tickle Time! (A Boynton on Board Book) Online, Read Best Book Tickle Time! (A Boynton on Board Book) Online, Pdf Books Tickle Time! (A Boynton on -

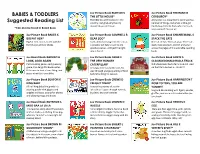

BABIES & TODDLERS Suggested Reading List

Juv Picture Book BURTON V Juv Picture Book FREEMAN D BABIES & TODDLERS THE LITTLE HOUSE* CORDUROY* The little house first stood in the A toy bear in a department store wants a Suggested Reading List country, but gradually the city number of things, but when a little girl moved closer and closer. finally buys him, he finds what he has al- *Can also be found in Board Book ways wanted most of all. Juv Picture Book BAKER K Juv Picture Book CAMPBELL R Juv Picture Book GHAHREMANI, S BIG FAT HEN* DEAR ZOO* STACK THE CATS Big Fat Hen counts to ten with her Each animal arriving from the zoo as One cat sleeps. Two cats play. Three cats friends and all their chicks. a possible pet fails to suit its pro- stack! Cats scamper, stretch and yawn spective owner, until just the right across the pages of this adorable counting one is found. book. Juv Board Book BARUZZI A Juv Picture Book CARLE E Juv Picture Book GOETZ S LOOK, LOOK AGAIN THE VERY HUNGRY OLD MACDONALD HAD A TRUCK Part counting game, part guessing CATERPILLAR* Old MacDonald had a farm E-I-E-I-O. And game, this delightful book invites A hungry little caterpillar eats his on that farm he had a...TRUCK?! little ones to look at one thing, and way through a large quantity of food guess what else it could be. before building his cocoon. Juv Picture Book BEATON K Juv Picture Book CREWS D Juv Picture Book HARRINGTON T KING BABY FREIGHT TRAIN* NOSE TO TOES, YOU ARE All hail King Baby! He greets his Traces the journey of a color- YUMMY! adoring public with giggles and ful train as it goes through tunnels, Sing and dance along with tigers, pandas, wiggles and coos, posing for photos by cities, and over trestles. -

View from the Archimedean Point

View from the Archimedean Point Susanne Kass Degree Thesis for Entrepreneurship in the Arts, Master of Culture and Art Master Degree Programme in Culture and Art Novia University of Applied Sciences Jakobstad 2016, Finland MASTER’S THESIS Author: Susanne Kass Degree Programme: Master of Culture and Arts Specialization: Entrepreneurship in the Arts Supervisors: Power Ekroth and Emma Westerlund Title: View from the Archimedean point ________________________________________________________ Date: 13.4.2016 Appendices: 2 Number of pages: 71 ________________________________________________________ Summary View from the Archimedean Point attempts to develop a method of reading art which draws on the theories of vision initiated by ancient Greek philosopher Archimedes and developed by Hannah Arendt in The Human Condition. Archimedes speculated that if he could find solid ground on which to stand and a long lever that he could shift the Earth. From this place he would also have a view of totality removed and distinguishable from the view allowed by his regular human capacities. Arendt developed this idea in relation to Descartes and the modern viewpoint which is assisted by technology. Here I attempt to outline the ways that artistic practice is connected to the human condition and how art has been affected by the many advancements in technology in both a practical and abstract sense. Digital tools may be useful but they can also radically affect values systems related to economic but also social and cultural value. By outlining some of the mechanisms which allow these shifts to occur and showing how images and ideas have functioned as Archimedean points in the past, I hope that it will give a basis for the model of using the Archimedean point as a tool for reading and thinking about art, which are then presented in applied examples from my own work in the appendices. -

New Archimedean Point for Intelligence and Foreign Policy - Reflexivity, Complexity & Culture

New Archimedean Point for Intelligence and Foreign Policy - Reflexivity, Complexity & Culture Lowell F. Christy Jr. Ph.D. Cultural Strategies Institute The talk/paper will expose the narrow epistemological foundations of current embodiments in Intelligence and Foreign Policy that results in Intelligence Failure, Blowback and Policy Missteps. Through the lens of the seven "sins" of omission or commission underlying current institutionalized concepts of art/craft of intelligence and formation/execution of foreign policy, the paper will propose HOW reflexivity, complexity and culture can overcome our epistemic malaise. The structure of the argument is based on case studies of METHODS for the use of mind resulting in a proposed TOOL KIT for establishing SUPPLY CHAINS of data, information, knowledge & wisdom (DIKW) that could rise to the mantle of "intelligence." There is an epistemological (science of knowing) revolution brewing in the worlds of intelligence and foreign policy. Paradigms of the past of what constitutes intelligence and how we perceive and interact with the "Other." are now counter productive. A breed of "warriors of the mind" are basing change on a new relationship between epistemology and ecology systems – an ecology of minds. Instead of the touch stones of truth based on being outside the system (God, Form, Reason, Science), intelligence is now being redefined as fields of self organizing, information processing organisms/organizations. What will the new intelligence and foreign policy look like? An Archimedean point (Punctum Archimedis")is a hypothetical perspective from which an observer can objectively perceive the subject of inquiry, with a view to the totality. The method of "removing oneself" from the object of study so that one can see it in relations to all other things has characterized Western thought from the Greeks, Medieval Europe, Western Enlightenment right up to the ways our intelligence agencies and foreign policy is conducted. -

Publishers/Distributors of Children's Books in Languages Other Than

Where to Find Linguistically and Culturally Diverse Children’s Books Lectorum (www.lectorum.com) Lectorum has more than 25,000 titles of Spanish-language books for adults and children. They are the exclusive U.S. distributor of children’s books by world-class publishing companies including: Anaya, Bruño, Corimbo, Edebé, Edilupa, Ekaré, Entrelibros, Everest, Fondo de Cultura Económica, Global, ING Editores, La Galera, Juventud, Kalandraka, Kókinos, Litexsa, Lóguez, Melhoramentos, Molino, Noguer, Serres, and Tandem. Lectorum is also the sole distributor of the Harry Potter series in Spanish in the U.S and Puerto Rico. LEE & LOW BOOKS (www.leeandlow.com) LEE & LOW BOOKS is an independent children's book publisher specializing in multicultural themes. Its goal is to meet the need for stories that children of color can identify with and that all children can enjoy. LEE & LOW makes a special effort to work with artists of color, and takes pride in nurturing many authors and illustrators who are new to the world of children’s book publishing. LEE & LOW BOOKS has published over 200 titles in hardcover, paperback, lift-the-flap, and board book formats. Many of their titles are translated into Spanish. Kane Miller Books (www.kanemiller.com) Kane Miller is a very small, specialized, independent publishing company. The web site states: “We believe that children's books should comfort and challenge, that they should awaken the imagination and the conscience. We publish books we think are important to bring to American children. We truly believe in bringing the world closer to a child and the children of the world closer to each other. -

Philosophy 427 Intuitions and Philosophy

Philosophy 427 Intuitions and Philosophy Russell Marcus Hamilton College Fall 2009 Class 2: Foundationalism Marcus, Intuitions and Philosophy, Fall 2009, Slide 1 Two foundationalist projects in the modern era P Rationalism, epitomized by Descartes P Empiricism, epitomized by Locke and Hume Marcus, Intuitions and Philosophy, Fall 2009, Slide 2 Descartes’s Meditations P Three skeptical hypotheses < Sense illusion < Dreaming < Demon deceiver P A “single Archimedean point”: knowledge of his mind: “I am, I exist, as long as I am thinking.” P God’s existence P A method of securing all the rest of his knowledge, ensured by the goodness of God P The rest of the details < the new Galilean science < some orthodox religious beliefs Marcus, Intuitions and Philosophy, Fall 2009, Slide 3 The synthetic presentation P Based on Euclid’s Elements < foundational claims in geometry gain universal agreement < metaphysical foundations are less obvious to the folk P The Elements < definitions: mainly unproblematic < five more general logical axioms, or common notions – not in question in geometry – In metaphysics, they are more contentious < five geometric postulates < The remaining propositions Marcus, Intuitions and Philosophy, Fall 2009, Slide 4 The parallel postulate P If a straight line falling on two straight a lines makes the interior angles on the same side less than two right angles, b the two straight lines, if produced indefinitely, meet on that side on a+b < ð which are the angles less than the two right angles. P Playfair’s postulate: given a line, and a point not on that line, there exists exactly one line which passes through the given point parallel to the given line. -

Books for Infants and Toddlers

Appendix A Books for Infants and Toddlers Young children need to be immersed in a literacy-rich ask the librarian at your local library to give you a list of environment. A foundation for reading success begins award-winning picture books; likewise, do not hesitate as early as the first few months of life. Exposure to books to ask the salesperson at a local bookstore to provide this and caring adults nourishes literacy development. Books information. Chances are they will have a list of these and oral language are tools to help infants and toddlers award-winning books or can complete a computer search become familiar with language. Young children enjoy to obtain this information for you. On-line merchants handling books and listening to stories. Infants and should also be able to provide you this information. toddlers enjoy the visual and auditory stimulation of You should also review the illustrations for size and having books read to them over and over again. quality before selecting a picture book. Study them Books help very young children by: carefully. You will notice a wide variety of illustration types in books for infants and toddlers. There are photo- 9 Developing visual discrimination skills graphs, watercolors, line drawings, and collages. As you 9 Developing visual memory skills review books, remember that infants and toddlers need 9 Developing listening skills to have large, realistic illustrations. Realistic illustrations serve two purposes: They help the young children main- 9 Developing auditory memory skills tain their interest in the book and they help develop 9 Presenting new and interesting information concept formation. -

Adventuring with Books: a Booklist for Pre-K-Grade 6. the NCTE Booklist

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 311 453 CS 212 097 AUTHOR Jett-Simpson, Mary, Ed. TITLE Adventuring with Books: A Booklist for Pre-K-Grade 6. Ninth Edition. The NCTE Booklist Series. INSTITUTION National Council of Teachers of English, Urbana, Ill. REPORT NO ISBN-0-8141-0078-3 PUB DATE 89 NOTE 570p.; Prepared by the Committee on the Elementary School Booklist of the National Council of Teachers of English. For earlier edition, see ED 264 588. AVAILABLE FROMNational Council of Teachers of English, 1111 Kenyon Rd., Urbana, IL 61801 (Stock No. 00783-3020; $12.95 member, $16.50 nonmember). PUB TYPE Books (010) -- Reference Materials - Bibliographies (131) EDRS PRICE MF02/PC23 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Annotated Bibliographies; Art; Athletics; Biographies; *Books; *Childress Literature; Elementary Education; Fantasy; Fiction; Nonfiction; Poetry; Preschool Education; *Reading Materials; Recreational Reading; Sciences; Social Studies IDENTIFIERS Historical Fiction; *Trade Books ABSTRACT Intended to provide teachers with a list of recently published books recommended for children, this annotated booklist cites titles of children's trade books selected for their literary and artistic quality. The annotations in the booklist include a critical statement about each book as well as a brief description of the content, and--where appropriate--information about quality and composition of illustrations. Some 1,800 titles are included in this publication; they were selected from approximately 8,000 children's books published in the United States between 1985 and 1989 and are divided into the following categories: (1) books for babies and toddlers, (2) basic concept books, (3) wordless picture books, (4) language and reading, (5) poetry. (6) classics, (7) traditional literature, (8) fantasy,(9) science fiction, (10) contemporary realistic fiction, (11) historical fiction, (12) biography, (13) social studies, (14) science and mathematics, (15) fine arts, (16) crafts and hobbies, (17) sports and games, and (18) holidays. -

Book Types: Board Book, Touch and Feel Book, Textbook, Coloring

board book, touch and feel book, textbook, coloring book, sound book, photo Book Types: album, story book, pop-up book, drawing book, scratch book, 2D puzzle, note book, activity book, sticker book. Art paper(Coated paper), Grey card board(white board), ivory board, black board, Materials: Corrugated paper, Kraft paper, Fancy paper, Paper board And Wood free paper and as per customer specifications. Size: L*W*H (cm) according to customers' specific requirements Shape: Rectangle, square, round, oval, special Shape and customized accepted Printing: CMKY 4 color offset printing, Panton color printing OEM and ODM are available, and we can printing the LOGO, that the customers Brand: supply. electronic components, pen with different material, pigment magnet, ribbon, Accessories: plastic tray, sponge, blister, flowers, PVC/PET/PP window, flocking, velvet, satin or other fabric lined and as per customer specifications. Surface Glossy or matte lamination, glossy or matte varnish, UV varnish, UV coating, finishing: spot UV, embossing, debossing, hot stamping and more Foil-Stamping. Perfect Binding, Section Sewn, Side Wire Stitching, Saddle Stitching, Wire Side- Book blinding: Stitching, Plastic Spiral, Full Canadian Wire-o, Double Loop Wire-o, Half- Canadian Wire-o. Products are packed by standard export carton or according to customers' Packaging: requirements Delivery lead- 7-25days after receive customers deposit (depend on the quantity of order) time PDF, Adobe Illustrator, Adobe InDesign, Photoshop (Higher than 300dpi) all are Art Work: acceptable.. -

Download Hello Baby Words a Highcontrast Board Book Pdf Ebook by Roger Priddy

Download Hello Baby Words A HighContrast Board Book pdf ebook by Roger Priddy You're readind a review Hello Baby Words A HighContrast Board Book ebook. To get able to download Hello Baby Words A HighContrast Board Book you need to fill in the form and provide your personal information. Book available on iOS, Android, PC & Mac. Gather your favorite books in your digital library. * *Please Note: We cannot guarantee the availability of this book on an database site. Book Details: Original title: Hello Baby: Words: A High-Contrast Board Book Age Range: 12 and up Grade Level: Preschool and up Series: Hello Baby Board book: 16 pages Publisher: Priddy Books; Brdbk edition (May 14, 2013) Language: English ISBN-10: 0312515987 ISBN-13: 978-0312515980 Product Dimensions:5.3 x 1 x 5.4 inches File Format: PDF File Size: 9838 kB Description: From a bright yellow sun to a juicy red strawberry, the high-contrast pictures in this board book will captivate babies. The alternating black and white backgrounds allow babies to focus on both the clearly defined pictures and the contrasting colors, as they look at and learn their very first words.... Review: I was expecting a lot of black and white with some red, but this book is like every other child’s book. One word pictures.... Ebook Tags: Hello Baby Words A HighContrast Board Book pdf book by Roger Priddy in pdf books Hello Baby Words A HighContrast Board Book hello board a words highcontrast baby book ebook words book baby a hello pdf a book baby highcontrast words book hello words book board a highcontrast baby fb2 Hello Baby Words A HighContrast Board Book Then again, he spanks her to make her a book person and thats the hello kind of spankings. -

Campbell Presentation

Campbell Presentation Pan Macmillan A STEAM novelty board book series for preschoolers, introducing them to individuals who changed the world 9781529035391 9781529035407 9781529036046 9781529036039 Board Book Board Book Board Book Board Book April 2020 April 2020 August 2020 August 2020 £5.99 £5.99 £5.99 £5.99 • Publishing into the STEAM trend for stories about historical figures and role models for younger readers • With scenes to explore, fun facts to learn, bright, bold illustrations, and push, pull and slide mechanisms Ages 0 - 5 Eco Warriors Nila Aye A novelty board book for preschoolers, introducing them to eco warriors who changed the world • Discover the environmental heroes who changed our world • Fits in to the current STEM trend for stories about historical figures and role models for younger readers • Little ones learn as they play with novelty mechanisms and with bitesize facts on every spread • Each title very simply explores the thinking, approach and actions of several influential figures from a particular field 9781529036046 Board Book August 2020 £5.99 Ages 1+ A novelty board book introducing emotional intelligence to young children, with tips for parents and carers from an Early Years expert Marie Paruit 9781529023367 9781529023374 9781529029789 9781529029802 Board Book Board Book Board Book Board Book May 2020 May 2020 September 2020 September 2020 £6.99 £6.99 £6.99 £6.99 • Explore feelings safely, with gentle stories and interactive novelties, including flaps, sliding tabs and a wheel • Enables adults to understand