Tool Use by Green Jays

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Spring in South Texas

SPRING IN SOUTH TEXAS MARCH 31–APRIL 9, 2019 Green Jay, Quinta Mazatlan, McAllen, Texas, April 5, 2019, Barry Zimmer LEADERS: BARRY ZIMMER & JACOB DRUCKER LIST COMPILED BY: BARRY ZIMMER VICTOR EMANUEL NATURE TOURS, INC. 2525 WALLINGWOOD DRIVE, SUITE 1003 AUSTIN, TEXAS 78746 WWW.VENTBIRD.COM SPRING IN SOUTH TEXAS MARCH 31–APRIL 9, 2019 By Barry Zimmer Once again, our Spring in South Texas tour had it all—virtually every South Texas specialty, wintering Whooping Cranes, plentiful migrants (both passerine and non- passerine), and rarities on several fronts. Our tour began with a brief outing to Tule Lake in north Corpus Christi prior to our first dinner. Almost immediately, we were met with a dozen or so Scissor-tailed Flycatchers lining a fence en route—what a welcoming party! Roseate Spoonbill, Crested Caracara, a very cooperative Long-billed Thrasher, and a group of close Cave Swallows rounded out the highlights. Strong north winds and unsettled weather throughout that day led us to believe that we might be in for big things ahead. The following day was indeed eventful. Although we had no big fallout in terms of numbers of individuals, the variety was excellent. Scouring migrant traps, bays, estuaries, coastal dunes, and other habitats, we tallied an astounding 133 species for the day. A dozen species of warblers included a stunningly yellow male Prothonotary, a very rare Prairie that foraged literally at our feet, two Yellow-throateds at arm’s-length, four Hooded Warblers, and 15 Northern Parulas among others. Tired of fighting headwinds, these birds barely acknowledged our presence, allowing unsurpassed studies. -

Birds & Butterflies of South Texas and the Rio Grande Valley

Birds & Butterflies of South Texas and the Rio Grande Valley Naturetrek Tour Itinerary Outline itinerary Day 1 Fly Austin, Texas & overnight Day 2/3 Knolle Farm Ranch, Aransas and Corpus Christi Day 4/6 Chachalaca, lower Rio Grande Valley Day 7/9 The Alamo Inn, middle Rio Grande Valley Day 10 Knolle Farm Ranch Day 11 Choke Canyon State Park & San Antonio Day 12/13 Depart Austin / arrive London Departs November Focus Birds, butterflies, some mammals and reptiles Grading A. Easy walking Dates and Prices See www.naturetrek.co.uk (tour code USA15) or the current Naturetrek brochure Highlights • Relaxed pace of birding and butterfly-watching • Stay in famous ‘birding inns’ • Over 300 species of butterfly recorded • Whooping Cranes at Aransas Wildlife Refuge • Rio Grande specialities such as Green Jay and From top: Green Jay, Queen, Whooping Crane (images by Jane Dixon Altamira Oriole, plus other rarities and migrants and Adam Dudley) Naturetrek Mingledown Barn Wolf’s Lane Chawton Alton Hampshire GU34 3HJ UK T: +44 (0)1962 733051 E: [email protected] W: www.naturetrek.co.uk Birds & Butterflies of South Texas and the Rio Grande Valley Tour Itinerary Introduction The lower Rio Grande Valley of Texas is one of the most exciting areas in North America for birds and butterflies. From Falcon Dam in the north to South Padre Island on the coast, this region is famous among naturalists as the key place to see an exciting range of wildlife found nowhere else in the United States. Subtropical habitats along the lower Rio Grande Valley form an extension of Mexico’s 'Tamaulipan Biotic Province', home to species characteristic of north-eastern Mexico, and an explosion of butterfly gardens throughout the valley has resulted in more species of butterfly being recorded here than in any other region of the country. -

Songbird Remix Africa

Avian Models for 3D Applications Characters and Procedural Maps by Ken Gilliland 1 Songbird ReMix Cool ‘n’ Unusual Birds 3 Contents Manual Introduction and Overview 3 Model and Add-on Crest Quick Reference 4 Using Songbird ReMix and Creating a Songbird ReMix Bird 5 Field Guide List of Species 9 Parrots and their Allies Hyacinth Macaw 10 Pigeons and Doves Luzon Bleeding-heart 12 Pink-necked Green Pigeon 14 Vireos Red-eyed Vireo 16 Crows, Jays and Magpies Green Jay 18 Inca or South American Green Jay 20 Formosan Blue Magpie 22 Chickadees, Nuthatches and their Allies American Bushtit 24 Old world Warblers, Thrushes and their Allies Wrentit 26 Waxwings Bohemian Waxwing 28 Larks Horned or Shore Lark 30 Crests Taiwan Firecrest 32 Fairywrens and their Allies Purple-crowned Fairywren 34 Wood Warblers American Redstart 37 Sparrows Song Sparrow 39 Twinspots Pink-throated Twinspot 42 Credits 44 2 Opinions expressed on this booklet are solely that of the author, Ken Gilliland, and may or may not reflect the opinions of the publisher, DAZ 3D. Songbird ReMix Cool ‘n’ Unusual Birds 3 Manual & Field Guide Copyrighted 2012 by Ken Gilliland - www.songbirdremix.com Introduction The “Cool ‘n’ Unusual Birds” series features two different selections of birds. There are the “unusual” or “wow” birds such as Luzon Bleeding Heart, the sleek Bohemian Waxwing or the patterned Pink-throated Twinspot. All of these birds were selected for their spectacular appearance. The “Cool” birds refer to birds that have been requested by Songbird ReMix users (such as the Hyacinth Macaw, American Redstart and Red-eyed Vireo) or that are personal favorites of the author (American Bushtit, Wrentit and Song Sparrow). -

Federal Register/Vol. 85, No. 74/Thursday, April 16, 2020/Notices

21262 Federal Register / Vol. 85, No. 74 / Thursday, April 16, 2020 / Notices acquisition were not included in the 5275 Leesburg Pike, Falls Church, VA Comment (1): We received one calculation for TDC, the TDC limit would not 22041–3803; (703) 358–2376. comment from the Western Energy have exceeded amongst other items. SUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION: Alliance, which requested that we Contact: Robert E. Mulderig, Deputy include European starling (Sturnus Assistant Secretary, Office of Public Housing What is the purpose of this notice? vulgaris) and house sparrow (Passer Investments, Office of Public and Indian Housing, Department of Housing and Urban The purpose of this notice is to domesticus) on the list of bird species Development, 451 Seventh Street SW, Room provide the public an updated list of not protected by the MBTA. 4130, Washington, DC 20410, telephone (202) ‘‘all nonnative, human-introduced bird Response: The draft list of nonnative, 402–4780. species to which the Migratory Bird human-introduced species was [FR Doc. 2020–08052 Filed 4–15–20; 8:45 am]‘ Treaty Act (16 U.S.C. 703 et seq.) does restricted to species belonging to biological families of migratory birds BILLING CODE 4210–67–P not apply,’’ as described in the MBTRA of 2004 (Division E, Title I, Sec. 143 of covered under any of the migratory bird the Consolidated Appropriations Act, treaties with Great Britain (for Canada), Mexico, Russia, or Japan. We excluded DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR 2005; Pub. L. 108–447). The MBTRA states that ‘‘[a]s necessary, the Secretary species not occurring in biological Fish and Wildlife Service may update and publish the list of families included in the treaties from species exempted from protection of the the draft list. -

The Purplish Jay Rides Wild Ungulates to Pick Food

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/305469882 The Purplish Jay rides wild ungulates to pick food Article in Revista Brasileira de Ornitologia · July 2016 CITATIONS READS 0 29 1 author: Ivan Sazima University of Campinas 326 PUBLICATIONS 5,139 CITATIONS SEE PROFILE All in-text references underlined in blue are linked to publications on ResearchGate, Available from: Ivan Sazima letting you access and read them immediately. Retrieved on: 05 October 2016 Revista Brasileira de Ornitologia, 23(4), 365-367 article December 2015 The Purplish Jay rides wild ungulates to pick food Ivan Sazima1 1 Museu de Zoologia, Caixa Postal 6109, Universidade Estadual de Campinas, CEP 13083-970, Campinas, SP, Brazil. 1 Corresponding author: [email protected] Received on 15 April 2015. Accepted on 29 December 2015. ABstract: Corvids are renowned for their variable foraging behaviour, and about 20 species in eight genera perch on wild and domestic ungulates to pick ticks on the body of these mammals. Herein I illustrate and briefly comment on the Purplish Jay (Cyanocorax cyanomelas) riding deer and tapir in the Pantanal, Western Brazil. The jay perched on the head or back of the ungulates and searched for ticks, playing the role of a cleaner bird. Deer are rarely reported as hosts or clients of tick-picking birds in the Neotropics. The Purplish Jay is the southernmost Neotropical cleaner corvid reported to date. Given their opportunistic foraging behaviour, a few other Cyanocorax jay species may occasionally play the cleaner role of wild and domestic ungulates. KEY-WORDS: Cyanocorax cyanomelas, foraging, cleaning behaviour, Pantanal, Western Brazil. -

AOS Classification Committee – North and Middle America Proposal Set 2018-B 17 January 2018

AOS Classification Committee – North and Middle America Proposal Set 2018-B 17 January 2018 No. Page Title 01 02 Split Fork-tailed Swift Apus pacificus into four species 02 05 Restore Canada Jay as the English name of Perisoreus canadensis 03 13 Recognize two genera in Stercorariidae 04 15 Split Red-eyed Vireo (Vireo olivaceus) into two species 05 19 Split Pseudobulweria from Pterodroma 06 25 Add Tadorna tadorna (Common Shelduck) to the Checklist 07 27 Add three species to the U.S. list 08 29 Change the English names of the two species of Gallinula that occur in our area 09 32 Change the English name of Leistes militaris to Red-breasted Meadowlark 10 35 Revise generic assignments of woodpeckers of the genus Picoides 11 39 Split the storm-petrels (Hydrobatidae) into two families 1 2018-B-1 N&MA Classification Committee p. 280 Split Fork-tailed Swift Apus pacificus into four species Effect on NACC: This proposal would change the species circumscription of Fork-tailed Swift Apus pacificus by splitting it into four species. The form that occurs in the NACC area is nominate pacificus, so the current species account would remain unchanged except for the distributional statement and notes. Background: The Fork-tailed Swift Apus pacificus was until recently (e.g., Chantler 1999, 2000) considered to consist of four subspecies: pacificus, kanoi, cooki, and leuconyx. Nominate pacificus is highly migratory, breeding from Siberia south to northern China and Japan, and wintering in Australia, Indonesia, and Malaysia. The other subspecies are either residents or short distance migrants: kanoi, which breeds from Taiwan west to SE Tibet and appears to winter as far south as southeast Asia. -

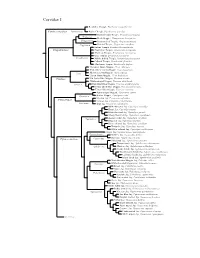

Corvidae Species Tree

Corvidae I Red-billed Chough, Pyrrhocorax pyrrhocorax Pyrrhocoracinae =Pyrrhocorax Alpine Chough, Pyrrhocorax graculus Ratchet-tailed Treepie, Temnurus temnurus Temnurus Black Magpie, Platysmurus leucopterus Platysmurus Racket-tailed Treepie, Crypsirina temia Crypsirina Hooded Treepie, Crypsirina cucullata Rufous Treepie, Dendrocitta vagabunda Crypsirininae ?Sumatran Treepie, Dendrocitta occipitalis ?Bornean Treepie, Dendrocitta cinerascens Gray Treepie, Dendrocitta formosae Dendrocitta ?White-bellied Treepie, Dendrocitta leucogastra Collared Treepie, Dendrocitta frontalis ?Andaman Treepie, Dendrocitta bayleii ?Common Green-Magpie, Cissa chinensis ?Indochinese Green-Magpie, Cissa hypoleuca Cissa ?Bornean Green-Magpie, Cissa jefferyi ?Javan Green-Magpie, Cissa thalassina Cissinae ?Sri Lanka Blue-Magpie, Urocissa ornata ?White-winged Magpie, Urocissa whiteheadi Urocissa Red-billed Blue-Magpie, Urocissa erythroryncha Yellow-billed Blue-Magpie, Urocissa flavirostris Taiwan Blue-Magpie, Urocissa caerulea Azure-winged Magpie, Cyanopica cyanus Cyanopica Iberian Magpie, Cyanopica cooki Siberian Jay, Perisoreus infaustus Perisoreinae Sichuan Jay, Perisoreus internigrans Perisoreus Gray Jay, Perisoreus canadensis White-throated Jay, Cyanolyca mirabilis Dwarf Jay, Cyanolyca nanus Black-throated Jay, Cyanolyca pumilo Silvery-throated Jay, Cyanolyca argentigula Cyanolyca Azure-hooded Jay, Cyanolyca cucullata Beautiful Jay, Cyanolyca pulchra Black-collared Jay, Cyanolyca armillata Turquoise Jay, Cyanolyca turcosa White-collared Jay, Cyanolyca viridicyanus -

The White-Throated Magpie-Jay

THE WHITE-THROATED MAGPIE-JAY BY ALEXANDER F. SKUTCH ORE than 15 years have passed since I was last in the haunts of the M White-throated Magpie-Jay (Calocitta formosa) . During the years when I travelled more widely through Central America I saw much of this bird, and learned enough of its habits to convince me that it would well repay a thorough study. Since it now appears unlikely that I shall make this study myself, I wish to put on record such information as I gleaned, in the hope that these fragmentary notes will stimulate some other bird- watcher to give this jay the attention it deserves. A big, long-tailed bird about 20 inches in length, with blue and white plumage and a high, loosely waving crest of recurved black feathers, the White-throated Magpie-Jay is a handsome species unlikely to be confused with any other member of the family. Its upper parts, including the wings and most of the tail, are blue or blue-gray with a tinge of lavender. The sides of the head and all the under plumage are white, and the outer feathers of the strongly graduated tail are white on the terminal half. A narrow black collar crosses the breast and extends half-way up each side of the neck, between the white and the blue. The stout bill and the legs and feet are black. The sexes are alike in appearance. The species extends from the Mexican states of Colima and Puebla to northwestern Costa Rica. A bird of the drier regions, it is found chiefly along the Pacific coast from Mexico southward as far as the Gulf of Nicoya in Costa Rica. -

Distribution Habitat and Social Organization of the Florida Scrub Jay

DISTRIBUTION, HABITAT, AND SOCIAL ORGANIZATION OF THE FLORIDA SCRUB JAY, WITH A DISCUSSION OF THE EVOLUTION OF COOPERATIVE BREEDING IN NEW WORLD JAYS BY JEFFREY A. COX A DISSERTATION PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE COUNCIL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 1984 To my wife, Cristy Ann ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I thank, the following people who provided information on the distribution of Florida Scrub Jays or other forms of assistance: K, Alvarez, M. Allen, P. C. Anderson, T. H. Below, C. W. Biggs, B. B. Black, M. C. Bowman, R. J. Brady, D. R. Breininger, G. Bretz, D. Brigham, P. Brodkorb, J. Brooks, M. Brothers, R. Brown, M. R. Browning, S. Burr, B. S. Burton, P. Carrington, K. Cars tens, S. L. Cawley, Mrs. T. S. Christensen, E. S. Clark, J. L. Clutts, A. Conner, W. Courser, J. Cox, R. Crawford, H. Gruickshank, E, Cutlip, J. Cutlip, R. Delotelle, M. DeRonde, C. Dickard, W. and H. Dowling, T. Engstrom, S. B. Fickett, J. W. Fitzpatrick, K. Forrest, D. Freeman, D. D. Fulghura, K. L. Garrett, G. Geanangel, W. George, T. Gilbert, D. Goodwin, J. Greene, S. A. Grimes, W. Hale, F. Hames, J. Hanvey, F. W. Harden, J. W. Hardy, G. B. Hemingway, Jr., 0. Hewitt, B. Humphreys, A. D. Jacobberger, A. F. Johnson, J. B. Johnson, H. W. Kale II, L. Kiff, J. N. Layne, R. Lee, R. Loftin, F. E. Lohrer, J. Loughlin, the late C. R. Mason, J. McKinlay, J. R. Miller, R. R. Miller, B. -

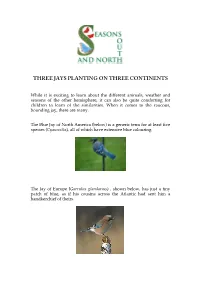

Three Jays Planting on Three Continents

THREE JAYS PLANTING ON THREE CONTINENTS While it is exciting to learn about the different animals, weather and seasons of the other hemisphere, it can also be quite comforting for children to learn of the similarities. When it comes to the raucous, bounding jay, there are many. The Blue Jay of North America (below) is a generic term for at least five species (Cyanocitta), all of which have extensive blue colouring. The Jay of Europe (Garrulus glandarius) , shown below, has just a tiny patch of blue, as if his cousins across the Atlantic had sent him a handkerchief of theirs. The Azure Jay (Cyanocorax caeruleus) of South America's Atlantic Rainforest (below) is like a regal relative with a deep blue cloak and a black hood. All are members of the crow family and it shows in their personalities. All are so well known for their habit of hiding seeds that they have become almost symbolic for it in each region. In late summer and early autumn when seeds from the great trees are falling, the jays on all three continents are greedy about trying to find as many seeds as possible to store. They hide them in logs, under leaves, in the earth, in anticipation of the lean times to come during the winter. Some they find later and eat; some they do not. Those they do not find often germinate and grow into trees. To people observing them, it seems as if they are intentionally planting the seeds and many stories about them doing so are told. In a time when forests are disappearing, reforestation has taken on urgency and almost a sacredness. -

Bird Species I Have Seen World List

bird species I have seen U.K tally: 279 US tally: 393 Total world: 1,496 world list 1. Abyssinian ground hornbill 2. Abyssinian longclaw 3. Abyssinian white-eye 4. Acorn woodpecker 5. African black-headed oriole 6. African drongo 7. African fish-eagle 8. African harrier-hawk 9. African hawk-eagle 10. African mourning dove 11. African palm swift 12. African paradise flycatcher 13. African paradise monarch 14. African pied wagtail 15. African rook 16. African white-backed vulture 17. Agami heron 18. Alexandrine parakeet 19. Amazon kingfisher 20. American avocet 21. American bittern 22. American black duck 23. American cliff swallow 24. American coot 25. American crow 26. American dipper 27. American flamingo 28. American golden plover 29. American goldfinch 30. American kestrel 31. American mag 32. American oystercatcher 33. American pipit 34. American pygmy kingfisher 35. American redstart 36. American robin 37. American swallow-tailed kite 38. American tree sparrow 39. American white pelican 40. American wigeon 41. Ancient murrelet 42. Andean avocet 43. Andean condor 44. Andean flamingo 45. Andean gull 46. Andean negrito 47. Andean swift 48. Anhinga 49. Antillean crested hummingbird 50. Antillean euphonia 51. Antillean mango 52. Antillean nighthawk 53. Antillean palm-swift 54. Aplomado falcon 55. Arabian bustard 56. Arcadian flycatcher 57. Arctic redpoll 58. Arctic skua 59. Arctic tern 60. Armenian gull 61. Arrow-headed warbler 62. Ash-throated flycatcher 63. Ashy-headed goose 64. Ashy-headed laughing thrush (endemic) 65. Asian black bulbul 66. Asian openbill 67. Asian palm-swift 68. Asian paradise flycatcher 69. Asian woolly-necked stork 70. -

A Continental-Scale Evaluation of the Productivity Hypothesis in Explaining Geographic Variation of Bird Diversity Across 25 Years

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, IRVINE Scratching the niche: A continental-scale evaluation of the productivity hypothesis in explaining geographic variation of bird diversity across 25 years DISSERTATION submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in Ecology and Evolutionary Biology by LuAnna Lee Dobson Dissertation Committee: Professor Bradford A. Hawkins, Chair Distinguished Professor John C. Avise Professor Nancy T. Burley Professor Jennifer B. H. Martiny 2017 Chapter 1 © 2015 John Wiley & Sons, Inc. All other materials © 2017 LuAnna Lee Dobson DEDICATION To Christopher Alan James ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Page LIST OF FIGURES iv LIST OF TABLES v ACKNOWLEDGMENTS vi CURRICULUM VITAE vii ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION xii CHAPTER 1: The diversity and abundance of North American bird 1 assemblages fail to track changing primary productivity CHAPTER 2, Part I: Raw richness outperforms effort-adjusted richness in 33 estimating avian diversity using the Christmas Bird Count CHAPTER 2, Part II: Diversity without abundance: Minimal support for 60 the productivity hypothesis in explaining species richness of North American wintering bird assemblages CHAPTER 3: A broad-scale test of the productivity hypothesis using 97 energy-scaled avian abundance shows independence from primary productivity across 25 years of change iii LIST OF FIGURES Page Figure 1.1 Spatial relationship between summer species richness and productivity 24 Figure 1.2 Annual spatial regression r2s for summer relationships across time 25 Figure 1.3 Histogram of summer temporal regression slopes across space 26 Figure 1.4 Spatial regression statistics across Ecoregions 28 Figure 1.5 Temporal regression slopes by site-averaged productivity 30 Figure 1.B1 Temporal regression slopes mapped across North America 32 Figure 2.1.1 Maps of winter richness using linear standardization methods 52 Figure 2.1.2 Spatial regression r2 for richness vs.