Quasar and Supermassive Black Hole Evolution

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Quantum Detection of Wormholes Carlos Sabín

www.nature.com/scientificreports OPEN Quantum detection of wormholes Carlos Sabín We show how to use quantum metrology to detect a wormhole. A coherent state of the electromagnetic field experiences a phase shift with a slight dependence on the throat radius of a possible distant wormhole. We show that this tiny correction is, in principle, detectable by homodyne measurements Received: 16 February 2017 after long propagation lengths for a wide range of throat radii and distances to the wormhole, even if the detection takes place very far away from the throat, where the spacetime is very close to a flat Accepted: 15 March 2017 geometry. We use realistic parameters from state-of-the-art long-baseline laser interferometry, both Published: xx xx xxxx Earth-based and space-borne. The scheme is, in principle, robust to optical losses and initial mixedness. We have not observed any wormhole in our Universe, although observational-based bounds on their abundance have been established1. The motivation of the search of these objects is twofold. On one hand, the theoretical implications of the existence of topological spacetime shortcuts would entail a challenge to our understanding of deep physical principles such as causality2–5. On the other hand, typical phenomena attributed to black holes can be mimicked by wormholes. Therefore, if wormholes exist the identity of the objects in the center of the galaxies might be questioned6 as well as the origin of the already observed gravitational waves7, 8. For these reasons, there is a renewed interest in the characterization of wormholes9–11 and in their detection by classical means such as gravitational lensing12, 13, among others14. -

Active Galactic Nuclei: a Brief Introduction

Active Galactic Nuclei: a brief introduction Manel Errando Washington University in St. Louis The discovery of quasars 3C 273: The first AGN z=0.158 2 <latexit sha1_base64="4D0JDPO4VKf1BWj0/SwyHGTHSAM=">AAACOXicbVDLSgMxFM34tr6qLt0Ei+BC64wK6kIoPtCNUMU+oNOWTJq2wWRmSO4IZZjfcuNfuBPcuFDErT9g+hC09UC4h3PvJeceLxRcg20/W2PjE5NT0zOzqbn5hcWl9PJKUQeRoqxAAxGoskc0E9xnBeAgWDlUjEhPsJJ3d9rtl+6Z0jzwb6ETsqokLZ83OSVgpHo6754xAQSf111JoK1kTChN8DG+uJI7N6buYRe4ZBo7di129hJ362ew5NJGAFjjfm3V4m0nSerpjJ21e8CjxBmQDBogX08/uY2ARpL5QAXRuuLYIVRjooBTwZKUG2kWEnpHWqxiqE+MmWrcuzzBG0Zp4GagzPMB99TfGzGRWnekZya7rvVwryv+16tE0DysxtwPI2A+7X/UjASGAHdjxA2uGAXRMYRQxY1XTNtEEQom7JQJwRk+eZQUd7POfvboej+TOxnEMYPW0DraRA46QDl0ifKogCh6QC/oDb1bj9ar9WF99kfHrMHOKvoD6+sbuhSrIw==</latexit> <latexit sha1_base64="H7Rv+ZHksM7/70841dw/vasasCQ=">AAACQHicbVDLSgMxFM34tr6qLt0Ei+BCy0TEx0IoPsBlBWuFTlsyaVqDSWZI7ghlmE9z4ye4c+3GhSJuXZmxFXxdCDk599zk5ISxFBZ8/8EbGR0bn5icmi7MzM7NLxQXly5slBjGayySkbkMqeVSaF4DAZJfxoZTFUpeD6+P8n79hhsrIn0O/Zg3Fe1p0RWMgqPaxXpwzCVQfNIOFIUro1KdMJnhA+yXfX832FCsteVOOzgAobjFxG+lhGTBxpe+HrBOBNjiwd5rpZsky9rFUn5BXvgvIENQQsOqtov3QSdiieIamKTWNogfQzOlBgSTPCsEieUxZde0xxsOaurMNNPPADK85pgO7kbGLQ34k/0+kVJlbV+FTpm7tr97Oflfr5FAd6+ZCh0nwDUbPNRNJIYI52nijjCcgew7QJkRzitmV9RQBi7zgguB/P7yX3CxVSbb5f2z7VLlcBjHFFpBq2gdEbSLKugUVVENMXSLHtEzevHuvCfv1XsbSEe84cwy+lHe+wdR361Q</latexit> The power source of quasars • The luminosity (L) of quasars, i.e. how bright they are, can be as high as Lquasar ~ 1012 Lsun ~ 1040 W. • The energy source of quasars is accretion power: - Nuclear fusion: 2 11 1 ∆E =0.007 mc =6 10 W s g− -

A Multimessenger View of Galaxies and Quasars from Now to Mid-Century M

A multimessenger view of galaxies and quasars from now to mid-century M. D’Onofrio 1;∗, P. Marziani 2;∗ 1 Department of Physics & Astronomy, University of Padova, Padova, Italia 2 National Institute for Astrophysics (INAF), Padua Astronomical Observatory, Italy Correspondence*: Mauro D’Onofrio [email protected] ABSTRACT In the next 30 years, a new generation of space and ground-based telescopes will permit to obtain multi-frequency observations of faint sources and, for the first time in human history, to achieve a deep, almost synoptical monitoring of the whole sky. Gravitational wave observatories will detect a Universe of unseen black holes in the merging process over a broad spectrum of mass. Computing facilities will permit new high-resolution simulations with a deeper physical analysis of the main phenomena occurring at different scales. Given these development lines, we first sketch a panorama of the main instrumental developments expected in the next thirty years, dealing not only with electromagnetic radiation, but also from a multi-messenger perspective that includes gravitational waves, neutrinos, and cosmic rays. We then present how the new instrumentation will make it possible to foster advances in our present understanding of galaxies and quasars. We focus on selected scientific themes that are hotly debated today, in some cases advancing conjectures on the solution of major problems that may become solved in the next 30 years. Keywords: galaxy evolution – quasars – cosmology – supermassive black holes – black hole physics 1 INTRODUCTION: TOWARD MULTIMESSENGER ASTRONOMY The development of astronomy in the second half of the XXth century followed two major lines of improvement: the increase in light gathering power (i.e., the ability to detect fainter objects), and the extension of the frequency domain in the electromagnetic spectrum beyond the traditional optical domain. -

A Supernova Origin for Dust in a High-Redshift Quasar

A SUPERNOVA ORIGIN FOR DUST IN A HIGH-REDSHIFT QUASAR R. Maiolino ∗, R. Schneider †∗, E. Oliva ‡∗, S. Bianchi §, A. Ferrara ¶, F. Mannucci§, M. Pedani‡, M. Roca Sogorb k ∗ INAF - Osservatorio Astrofisico di Arcetri, Largo Enrico Fermi 5, 50125 Firenze, Italy † “Enrico Fermi” Center, Via Panisperna 89/A, 00184 Roma, Italy ‡ Telescopio Nazionale Galileo, C. Alvarez de Abreu, 70, 38700 S.ta Cruz de La Palma, Spain § CNR-IRA, Sezione di Firenze, Largo Enrico Fermi 5, 50125 Firenze, Italy ¶ SISSA/International School for Advanced Studies, Via Beirut 4, 34100 Trieste, Italy k Astrofisico Fco. S`anchez, Universidad de La Laguna, 38206 La Laguna, Tenerife, Spain Interstellar dust plays a crucial role in the evolution of the Universe by assisting the formation of molecules1, by triggering the formation of the first low-mass stars2, and by absorbing stellar ultraviolet-optical light and subsequently re-emitting it at infrared/millimetre wavelengths. Dust is thought to be produced predominantly in the envelopes of evolved (age >1 Gyr), low-mass stars3. This picture has, however, recently been brought into question by the discovery of large masses of dust in the host galaxies of quasars4,5 at redshift z > 6, when the age of the Universe was less than 1 Gyr. Theoretical studies6,7,8, corroborated by observations of nearby supernova remnants9,10,11, have suggested that supernovae provide a fast and efficient dust formation environment in the early Universe. Here we report infrared observations of a quasar at redshift 6.2, which are used to obtain directly its dust extinction curve. We then show that such a curve is in excellent agreement with supernova dust models. -

Undergraduate Thesis on Supermassive Black Holes

Into the Void: Mass Function of Supermassive Black Holes in the local universe A Thesis Presented to The Division of Mathematics and Natural Sciences Reed College In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Bachelor of Arts Farhanul Hasan May 2018 Approved for the Division (Physics) Alison Crocker Acknowledgements Writing a thesis is a long and arduous process. There were times when it seemed further from my reach than the galaxies I studied. It’s with great relief and pride that I realize I made it this far and didn’t let it overpower me at the end. I have so many people to thank in very little space, and so much to be grateful for. Alison, you were more than a phenomenal thesis adviser, you inspired me to believe that Astro is cool. Your calm helped me stop freaking out at the end of February, when I had virtually no work to show for, and a back that ached with every step I took. Thank you for pushing me forward. Working with you in two different research projects were very enriching experiences, and I appreciate you not giving up on me, even after all the times I blanked on how to proceed forward. Thank you Johnny, for being so appreciative of my work, despite me bringing in a thesis that I myself barely understood when I brought it to your table. I was overjoyed when I heard you wanted to be on my thesis board! Thanks to Reed, for being the quirky, intellectual community that it prides itself on being. -

Chapter 22 Neutron Stars and Black Holes Units of Chapter 22 22.1 Neutron Stars 22.2 Pulsars 22.3 Xxneutron-Star Binaries: X-Ray Bursters

Chapter 22 Neutron Stars and Black Holes Units of Chapter 22 22.1 Neutron Stars 22.2 Pulsars 22.3 XXNeutron-Star Binaries: X-ray bursters [Look at the slides and the pictures in your book, but I won’t test you on this in detail, and we may skip altogether in class.] 22.4 Gamma-Ray Bursts 22.5 Black Holes 22.6 XXEinstein’s Theories of Relativity Special Relativity 22.7 Space Travel Near Black Holes 22.8 Observational Evidence for Black Holes Tests of General Relativity Gravity Waves: A New Window on the Universe Neutron Stars and Pulsars (sec. 22.1, 2 in textbook) 22.1 Neutron Stars According to models for stellar explosions: After a carbon detonation supernova (white dwarf in binary), little or nothing remains of the original star. After a core collapse supernova, part of the core may survive. It is very dense—as dense as an atomic nucleus—and is called a neutron star. [Recall that during core collapse the iron core (ashes of previous fusion reactions) is disintegrated into protons and neutrons, the protons combine with the surrounding electrons to make more neutrons, so the core becomes pure neutron matter. Because of this, core collapse can be halted if the core’s mass is between 1.4 (the Chandrasekhar limit) and about 3-4 solar masses, by neutron degeneracy.] What do you get if the core mass is less than 1.4 solar masses? Greater than 3-4 solar masses? 22.1 Neutron Stars Neutron stars, although they have 1–3 solar masses, are so dense that they are very small. -

Radio Observations of the Supermassive Black Hole at the Galactic Center and Its Orbiting Magnetar

Radio Observations of the Supermassive Black Hole at the Galactic Center and its Orbiting Magnetar Rebecca Rimai Diesing Honors Thesis Department of Physics and Astronomy Northwestern University Spring 2017 Honors Thesis Advisor: Farhad Zadeh ! Radio Observations of the Supermassive Black Hole at the Galactic Center and its Orbiting Magnetar Rebecca Rimai Diesing Department of Physics and Astronomy Northwestern University Honors Thesis Advisor: Farhad Zadeh Department of Physics and Astronomy Northwestern University At the center of our galaxy a bright radio source, Sgr A*, coincides with a black hole four million times the mass of our sun. Orbiting Sgr A* at a distance of 3 arc seconds (an estimated 0.1 pc) and rotating with a period of 3.76 s is a magnetar, or pulsar⇠ with an extremely strong magnetic field. This magnetar exhibited an X-ray outburst in April 2013, with enhanced, highly variable radio emission detected 10 months later. In order to better understand the behavior of Sgr A* and the magnetar, we study their intensity variability as a function of both time and frequency. More specifically, we present the results of short (8 minute) and long (7 hour) radio continuum observations, taken using the Jansky Very Large Array (VLA) over multiple epochs during the summer of 2016. We find that Sgr A*’s flux density (a proxy for intensity) is highly variable on an hourly timescale, with a frequency dependence that di↵ers at low (34 GHz) and high (44 GHz) frequencies. We also find that the magnetar remains highly variable on both short (8 min) and long (monthly) timescales, in agreement with observations from 2014. -

BLACK HOLES: the OTHER SIDE of INFINITY General Information

BLACK HOLES: THE OTHER SIDE OF INFINITY General Information Deep in the middle of our Milky Way galaxy lies an object made famous by science fiction—a supermassive black hole. Scientists have long speculated about the existence of black holes. German astronomer Karl Schwarzschild theorized that black holes form when massive stars collapse. The resulting gravity from this collapse would be so strong that the matter would become more and more dense. The gravity would eventually become so strong that nothing, not even radiation moving at the speed of light, could escape. Schwarzschild’s theories were predicted by Einstein and then borne out mathematically in 1939 by American astrophysicists Robert Oppenheimer and Hartland Snyder. WHAT EXACTLY IS A BLACK HOLE? First, it’s not really a hole! A black hole is an extremely massive concentration of matter, created when the largest stars collapse at the end of their lives. Astronomers theorize that a point with infinite density—called a singularity—lies at the center of black holes. SO WHY IS IT CALLED A HOLE? Albert Einstein’s 1915 General Theory of Relativity deals largely with the effects of gravity, and in essence predicts the existence of black holes and singularities. Einstein hypothesized that gravity is a direct result of mass distorting space. He argued that space behaves like an invisible fabric with an elastic quality. Celestial bodies interact with this “fabric” of space-time, appearing to create depressions termed “gravity wells” and drawing nearby objects into orbit around them. Based on this principle, the more massive a body is in space, the deeper the gravity well it will create. -

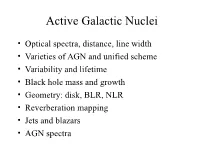

Active Galactic Nuclei

Active Galactic Nuclei • Optical spectra, distance, line width • Varieties of AGN and unified scheme • Variability and lifetime • Black hole mass and growth • Geometry: disk, BLR, NLR • Reverberation mapping • Jets and blazars • AGN spectra Optical spectrum of an AGN • Variety of different emission lines • Each line has centroid, area, width • There is also continuum emission Emission lines • Shift of line centroid gives recession velocity v/c = Δλ/λ. • The width is usually characterized by the “Full Width at Half Maximum”. For a Gaussian FHWM = 2.35σ. • The line width is determined by the velocity distribution of the line emitting gas, Δv/c = σ/λ. • Area is proportional to the number of detected line photons or the line flux. • Usually characterized by “equivalent width” or range in wavelength over which integration of the continuum produces the same flux as the line. Early observations of AGN • Very wide emission lines have been known since 1908. • In 1959, Woltjer noted that if the profiles are due to Doppler motion and the gas is gravitationally bound then v2 ~ GM/r. For v ~ 2000 km/s, we have 10 r M ≥10 ( 100 pc ) M Sun • So AGN, known at the time as Seyfert galaxies, must either have a very compact and luminous nucleus or be very massive. Quasars • Early radio telescopes found radio emission from stars, nebulae, and some galaxies. • There were also point-like, or star-like, radio sources which varied rapidly these are the `quasi-stellar’ radio sources or quasars. • In visible light quasars appear as points, like stars. Quasar optical spectra Redshift of 3C273 is 0.16. -

Stellar Death: White Dwarfs, Neutron Stars, and Black Holes

Stellar death: White dwarfs, Neutron stars & Black Holes Content Expectaions What happens when fusion stops? Stars are in balance (hydrostatic equilibrium) by radiation pushing outwards and gravity pulling in What will happen once fusion stops? The core of the star collapses spectacularly, leaving behind a dead star (compact object) What is left depends on the mass of the original star: <8 M⦿: white dwarf 8 M⦿ < M < 20 M⦿: neutron star > 20 M⦿: black hole Forming a white dwarf Powerful wind pushes ejects outer layers of star forming a planetary nebula, and exposing the small, dense core (white dwarf) The core is about the radius of Earth Very hot when formed, but no source of energy – will slowly fade away Prevented from collapsing by degenerate electron gas (stiff as a solid) Planetary nebulae (nothing to do with planets!) THE RING NEBULA Planetary nebulae (nothing to do with planets!) THE CAT’S EYE NEBULA Death of massive stars When the core of a massive star collapses, it can overcome electron degeneracy Huge amount of energy BAADE ZWICKY released - big supernova explosion Neutron star: collapse halted by neutron degeneracy (1934: Baade & Zwicky) Black Hole: star so massive, collapse cannot be halted SN1006 1967: Pulsars discovered! Jocelyn Bell and her supervisor Antony Hewish studying radio signals from quasars Discovered recurrent signal every 1.337 seconds! Nicknamed LGM-1 now called PSR B1919+21 BRIGHTNESS TIME NATURE, FEBRUARY 1968 1967: Pulsars discovered! Beams of radiation from spinning neutron star Like a lighthouse Neutron -

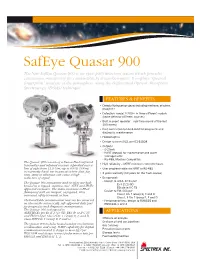

Safeye Quasar 900 the New Safeye Quasar 900 Is an Open Path Detection System Which Provides Continuous Monitoring for Combustible Hydrocarbon Gases

SafEye Quasar 900 The New SafEye Quasar 900 is an open path detection system which provides continuous monitoring for combustible hydrocarbon gases. It employs "spectral fingerprint" analysis of the atmosphere using the Differential Optical Absorption Spectroscopy (DOAS) technique. FEATURES & BENEFITS • Detects Hydrocarbon gases including methane, ethylene, propylene • Detection range: 4-200m in three different models (same detector different sources) • Built in event recorder – real time record of the last 100 events • Fast connection to Hand-Held for prognostic and diagnostic maintenance • Heated optics • Design to meet SIL2, per IEC61508 • Outputs: - 0-20mA - HART protocol for maintenance and asset managements - RS-485, Modbus Compatible The Quasar 900 consists of a Xenon Flash infrared transmitter and infrared receiver, separated over a • High reliability – MTBF minimum 100,000 hours line of sight from 13 ft (4m) up to 650 ft (200m) • User programmable via HART or RS-485 in extremely harsh environments where dust, fog, • 3 years warranty (10 years for the flash source) rain, snow or vibration can cause a high reduction of signal. • Ex approval: - Design to ATEX, IECEx per The Quasar 900 transmitter and receiver are both Ex II 2 (1) GD housed in a rugged, stainless steel, ATEX and IECEx approved enclosure. The main enclosure is EExd EEx de ia II C T5 flameproof with an integral, segregated, EExe - Design to FM, CSA per increased safety terminal section. Class I Div 1 Group B, C and D Class I, II Div 1 Group E, F and D The hand-held communication unit can be connected - Performance test: design to FM6325 and in-situ via the intrinsically safe approved data port EN50241-1 and 2 for prognostic and diagnostic maintenance. -

8. Active Galactic Nuclei. Radio Galaxies and Quasars

8. ACTIVE GALACTIC NUCLEI. RADIO GALAXIES AND QUASARS This Section starts analyzing the phenomenon of extragalactic Active Galactic Nuclei. Here we will essentially discuss their low-photon-energy emissions, while in Sect. 9 we will expand on the high-photon-energy ones. 8.1 Active Galactic Nuclei: Generalities We know that normal galaxies constitute the majority population of cosmic sources in 12 the local universe. Although they may be quite massive (up to 10 M), they are not 11 44 typically very luminous (never more luminous than 10 Lʘ10 erg/sec). For this reason normal galaxies have remained hardly detectable at very large cosmic distances for long time, with recent advances mostly thanks to technological observational improvements. For several decades, since the ’60, the only detectable objects at large cosmic distances belonged to a completely different class of sources, which did not derive their energy from thermonuclear burning in stars. These are the Active Galactic Nuclei, for which we use the acronym AGN. The galaxies hosting them are called active galaxies. For their luminosity, Active Galactic Nuclei and Active Galaxies have plaid a key role in the development of cosmology, further to the fact that they make one of the most important themes of extragalactic astrophysics and High Energy Astrophysics. Apparently, the interest for the Active Galaxies as a population might seem modest, as in the local universe they make a small fraction of normal galaxies, as summarized in the following. There are four main categories of Active Galaxies and AGN: 1. galaxies with an excess of infrared emission and violent activity of star formation (starburst), selected in particular in the far-IR, the luminous (LIRG), ultra-luminous (ULIRG) and hyper-luminous (HYLIRG) galaxies: the 3 classes 11 12 13 have bolometric luminosities >10 L (LIRG), >10 L (ULIRG), >10 L (HYLIRG); 2.