Massive Left Hemothorax Following Left Diaphragmatic and Splenic Rupture with Visceral Herniation: Case Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Delayed Massive Hemothorax Requiring

Clin Exp Emerg Med 2018;5(1):60-65 https://doi.org/10.15441/ceem.16.190 Case Report Delayed massive hemothorax requiring eISSN: 2383-4625 surgery after blunt thoracic trauma over a 5-year period: complicating rib fracture with sharp edge associated with diaphragm injury Received: 26 September 2017 Revised: 28 January 2018 Sung Wook Chang, Kyoung Min Ryu, Jae-Wook Ryu Accepted: 20 February 2018 Trauma Center, Department of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery, Dankook University Hospital, Cheonan, Korea Correspondence to: Jae-Wook Ryu Department of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery, Dankook Delayed massive hemothorax requiring surgery is relatively uncommon and can potentially be University Hospital, 201 Manghyang-ro, Dongnam-gu, Cheonan 31116, Korea life-threatening. Here, we aimed to describe the nature and cause of delayed massive hemotho- E-mail: [email protected] rax requiring immediate surgery. Over 5 years, 1,278 consecutive patients were admitted after blunt trauma. Delayed hemothorax is defined as presenting with a follow-up chest radiograph and computed tomography showing blunting or effusion. A massive hemothorax is defined as blood drainage >1,500 mL after closed thoracostomy and continuous bleeding at 200 mL/hr for at least four hours. Five patients were identified all requiring emergency surgery. Delayed mas- sive hemothorax presented 63.6±21.3 hours after blunt chest trauma. All patients had superfi- cial diaphragmatic lacerations caused by the sharp edge of a broken rib. The mean preoperative chest tube drainage was 3,126±463 mL. We emphasize the high-risk of massive hemothorax in patients who have a broken rib with sharp edges. -

Accuracy of Diagnosis of Distal Radial Fractures by Ultrasound Ahmad Saladdin Sultan, Muddather Abdul Aziz, Yakdhan Z

The Egyptian Journal of Hospital Medicine (October 2017) Vol. 69 (8), Page 3115-3122 Accuracy of Diagnosis of Distal Radial Fractures by Ultrasound Ahmad Saladdin Sultan, Muddather Abdul Aziz, Yakdhan Z. Alsaleem Mosul Teaching Hospital, Emergency Medicine Department, Mosul, Iraq Corresponding author: Ahmad Saladdin <[email protected] ABSTRACT Background: although distal radial fracture account up to 20% of all fractures, it forms the most common fracture in upper extremities. Distal radial fracture has six types the most common one is Colle's fracture. The gold standard for diagnosis of distal radial fracture is conventional radiograph. Despite using ultrasound in tendon rupture, localizing foreign bodies, ultrasound started to be used for diagnosing bone fracture especially distal radius. Aim of the work: this study aimed to detect the accuracy of ultrasound in the diagnosis of distal radial fracture. Patients and methods: this was a selective prospective case series study in the Emergency Department, Al-Jumhoori Teaching Hospital,78 patients were included in this study, their age ranged between 6-45 years with mean age 17.1. 59 were males and 19 females. Duration of the study was one year (January2013 - January 2014). Results: by analyzing data of 78 patients for distal radial fracture ultrasound and comparing the results with the gold standard conventional radiograph we found that sensitivity of ultrasound in detecting fracture was 95.5%, specificity 100%, accuracy 96.15%, positive predictive value 100% and negative predictive value 80%. Conclusion: results of the current work demonstrated that ultrasound can be considered as a promising alternative to routine radiograph in diagnosis of the distal radial fractures and the horizon still open for further studies of use of ultrasound in diagnosis of other types of fractures. -

Surgical Case Conference

Surgical Case Conference HENRY R. GOVEKAR, M.D. PGY-2 UNIVERSITY OF COLORADO HOSPITAL Objectives Introduce Patient Hospital Course Management of Injuries Decisions to make Outcome History and Physical 50y/o M who was transferred to Denver Health on post injury day #3. Patient involved in motorcycle collision in Vail; admit to local hospital. Patient riding with female companion, tight turn, laid down the bike on road, companion landing on top of patient. Companion suffered minor injuries including abrasions and knee pain History and Physical Our patient – c/o Right shoulder pain, left flank pain PMH: GERD; peptic ulcer PSH: hx of surgery for intractable ulcerative disease – distal gastrectomy with Billroth I, ? Of revision to Roux-en-Y gastrojejunostomy Meds: prilosec Social: denies tobacco; quit ETOH 13 years ago after MVC; denies IVDA NKDA History and Physical Exam per OSH: a&ox3, minor distress HR 110’s, BP 130/70’s, on NRB mask with sats 98% Multiple abrasions on scalp, arms , knees c/o right arm pain, left sided flank pain No other obvious injuries After fluid resuscitation – HD stable Sent to CT for abd/pelvis Post 10th rib fx Grade 3 splenic laceration Spleen Injury Scale Grade I Injury Grade IV injury http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/373694-media Grade V injury http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/373694-media What should our plan be? Management of Splenic Injuries Stable vs. Unstable Unstable – OR Stable – abd CT scan CT scan Other significant injury – OR Documented splenic injury Grade I, -

Treatment of Common Hip Fractures: Evidence Report/Technology

This report is based on research conducted by the Minnesota Evidence-based Practice Center (EPC) under contract to the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ), Rockville, MD (Contract No. HHSA 290 2007 10064 1). The findings and conclusions in this document are those of the authors, who are responsible for its content, and do not necessarily represent the views of AHRQ. No statement in this report should be construed as an official position of AHRQ or of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. The information in this report is intended to help clinicians, employers, policymakers, and others make informed decisions about the provision of health care services. This report is intended as a reference and not as a substitute for clinical judgment. This report may be used, in whole or in part, as the basis for the development of clinical practice guidelines and other quality enhancement tools, or as a basis for reimbursement and coverage policies. AHRQ or U.S. Department of Health and Human Services endorsement of such derivative products may not be stated or implied. Evidence Report/Technology Assessment Number 184 Treatment of Common Hip Fractures Prepared for: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality U.S. Department of Health and Human Services 540 Gaither Road Rockville, MD 20850 www.ahrq.gov Contract No. HHSA 290 2007 10064 1 Prepared by: Minnesota Evidence-based Practice Center, Minneapolis, Minnesota Investigators Mary Butler, Ph.D., M.B.A. Mary Forte, D.C. Robert L. Kane, M.D. Siddharth Joglekar, M.D. Susan J. Duval, Ph.D. Marc Swiontkowski, M.D. -

Traumatic Diaphragmatic Hernia: 28-Years Analysis at a Brazilian University Hospital

Traumatic diaphragmatic hernia: 28-years analysis at a Brazilian university hospital Vitor Kruger ( [email protected] ) State University of Campinas Thiago Calderan State University of Campinas Rodrigo Carvalho State University of Campinas Elcio Hirano State University of Campinas Gustavo Fraga State University of Campinas Research Article Keywords: Traumatic diaphragmatic hernia, diaphragm, hernia, diaphragmatic injury Posted Date: December 17th, 2020 DOI: https://doi.org/10.21203/rs.3.rs-121284/v1 License: This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Read Full License Page 1/16 Abstract Background The objective of the study is evaluate the approach to patients with acute traumatic diaphragmatic hernia at a Brazilian university hospital during a 28-year period. Traumatic diaphragmatic hernia is an uncommon injury, however its real incidence may be higher than expected. Sometimes is missed in trauma patients, and is usually associated with signicant morbidity and mortality, this analysis may improve outcomes for the trauma patient care. Methods Retrospective study of time series using and analisys database records of trauma patients at HC- Unicamp was performed to investigate the incidence, trauma mechanism, diagnosis, herniated organs, associated injuries, trauma score, morbidity, and mortality of this injury. Results Fifty-ve cases were analyzed. Blunt trauma was two-fold frequent than penetrating trauma, are associated with high grade injury and motor vehicle collision was the most common mechanism. Left side hernia was four-fold frequent than right side. Diagnose was mostly performed by chest radiography (31 cases; 56%). Associated intra-abdominal injuries were found in 37 patients (67.3%) and extra- abdominal injuries in 35 cases (63.6%). -

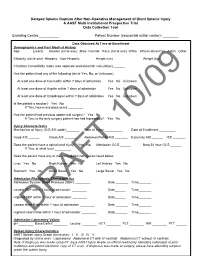

Delayed Splenic Rupture After Non-Operative Management of Blunt Splenic Injury a AAST Multi-Institutional Prospective Trial Data Collection Tool

Delayed Splenic Rupture After Non-Operative Management of Blunt Splenic Injury A AAST Multi-Institutional Prospective Trial Data Collection Tool Enrolling Center:__________ Patient Number (sequential within center): ________ Data Obtained At Time of Enrollment Demographics and Past Medical History Age: ______ (years) Gender (circle one): Male Female Race (circle one): White African-American Asian Other Ethnicity (circle one): Hispanic Non-Hispanic Height (cm) _______ Weight (kg) ______ Charlson Comorbidity Index (see separate worksheet for calculation) ______ Has the patient had any of the following (circle Yes, No, or Unknown): At least one dose of Coumadin within 7 days of admission Yes No Unknown At least one dose of Aspirin within 7 days of admission Yes No Unknown At least one dose of Clopidrogrel within 7 days of admission Yes No Unknown Is the patient a smoker? Yes No If Yes, how many pack-years ________ Has the patient had previous abdominal surgery? Yes No If Yes, is the only surgery patient has had laproscopic? Yes No Injury Characteristics Mechanism of Injury (ICD-9 E-code):_______ Date of Injury __________ Date of Enrollment _________ Head AIS ______ Chest AIS _______ Abdomen/Pelvis AIS _______ Extremity AIS ______ ISS _______ Does the patient have a spinal cord injury? Yes No Admission GCS ______ Best 24 hour GCS ______ If Yes, at what level _________ Does the patient have any of the intra-abdominal injuries listed below: Liver Yes No Right Kidney Yes No Left Kidney Yes No Stomach Yes No Small Bowel Yes No Large Bowel Yes -

Laparoscopic Repair of Chronic Traumatic Diaphragmatic Hernia Using Biologic Mesh with Cholecystectomy for Intrathoracic Gallbladder

CASE REPORT Laparoscopic Repair of Chronic Traumatic Diaphragmatic Hernia using Biologic Mesh with Cholecystectomy for Intrathoracic Gallbladder Jonathan Pulido, MD, Steven Reitz, MD, Suzanne Gozdanovic, MD, Phillip Price, MD ABSTRACT INTRODUCTION Background and Objectives: Diaphragmatic rupture is a Traumatic diaphragmatic hernias have been well de- serious complication of both blunt and penetrating ab- scribed after blunt trauma. Diaphragmatic ruptures can dominal trauma. In the acute setting, delay in diagnosis occur in up to 0.8% to 7% of blunt abdominal trauma, with can lead to severe cardiovascular and respiratory compro- large left-sided defects being the most common.1-4 If the mise. Chronic cases can present years later with a plethora injury is not recognized, progressive herniation of abdom- of clinical symptoms. Laparoscopic techniques are being inal contents may ensue. It is estimated that approximately increasingly utilized in the diagnosis and treatment of 40% to 62% of ruptured diaphragms are missed during the traumatic diaphragmatic hernias. acute hospital stay.1 The time delay to presentation has been reported to be from several weeks to 50 years.3 Method: We describe a case of a 70-year-old female who presented with signs and symptoms of a small bowel Although minimally invasive techniques have been uti- obstruction. She was ultimately found to have an obstruc- lized in the surgical repair of both acute diaphragmatic tion secondary to a chronic traumatic diaphragmatic her- lacerations and chronic traumatic diaphragmatic hernias, nia with an intrathoracic gallbladder and incarcerated its use has not been well defined or universally accepted. small intestine. A cholecystectomy and diaphragmatic her- nia repair were both performed laparoscopically. -

Spleen Trauma

Guideline for Management of Spleen Trauma Minor injury HDS Ward Observation Grade I - II STICU Observation Hemodynamically Contrast- Moderate Stable enhanced CTS Injury +/- local HDS exploration in SW Grade III-V Contrast extravasation Angioembolization (A/E) Pseudoaneurysm Spleen Injury Ongoing bleeding HDS DeteriorationGrade I - II Unstable Unsuccessful or rebleeding Hemodynamically Splenectomy Repeat eFAST Positive Laparotomy eFAST Unstable Unstable CBC, ABG, Lactate POC INR Stable Type and Cross Splenic salvage or splenectomy Negative Positive Consider DPA Negative Evaluate for other causes of instability Guideline for Management of Spleen Trauma -NOM in splenic injuries is contraindicated in the setting of unresponsive hemodynamic instability or other indicates for laparotomy (peritonitis, hollow organ injuries, bowel evisceration, impalement) -AG/AE may be considered the first-line intervention in patients with hemodynamic stability and arterial blush on CT scan irrespective from injury grade - Age above 55 years old, high ISS, and moderate to severe splenic injuries are prognostic factors for NOM failure. -Age above 55 years old alone, large hemoperitoneum alone, hypotension before resuscitation, GCS < 12 and low-hematocrit level at the admission, associated abdominal injuries, blush at CT scan, anticoagulation drugs, HIV disease, drug addiction, cirrhosis, and need for blood transfusions should be taken into account, but they are not absolute contraindications for NOM but are at higher risk of failure and STICU observation is -

Management of Adult Blunt Splenic Trauma

Review Article The Journal of TRAUMA Injury, Infection, and Critical Care Western Trauma Association (WTA) Critical Decisions in Trauma: Management of Adult Blunt Splenic Trauma Frederick A. Moore, MD, James W. Davis, MD, Ernest E. Moore, Jr., MD, Christine S. Cocanour, MD, Michael A. West, MD, and Robert C. McIntyre, Jr., MD 09/30/2020 on BhDMf5ePHKav1zEoum1tQfN4a+kJLhEZgbsIHo4XMi0hCywCX1AWnYQp/IlQrHD3Ypodx1mzGi19a2VIGqBjfv9YfiJtaGCC1/kUAcqLCxGtGta0WPrKjA== by http://journals.lww.com/jtrauma from Downloaded J Trauma. 2008;65:1007–1011. Downloaded his is a position article from members of the Western geons were focused on perfecting operative splenic salvage from 1–3 http://journals.lww.com/jtrauma Trauma Association (WTA). Because there are no pro- techniques, the pediatric surgeons provided convincing Tspective randomized trials, the algorithm (Fig. 1) is evidence that the best way to salvage the spleen was not to based on the expert opinion of WTA members and published operate.4–6 Adult trauma surgeons were slow to adopt non- observational studies. We recognize that variability in deci- operative management (NOM) because early reports of its sion making will continue. We hope this management algo- use in adults documented a 30% to 70% failure rate of which by rithm will encourage institutions to develop local protocols two-thirds underwent total splenectomy.7–10 There was also a BhDMf5ePHKav1zEoum1tQfN4a+kJLhEZgbsIHo4XMi0hCywCX1AWnYQp/IlQrHD3Ypodx1mzGi19a2VIGqBjfv9YfiJtaGCC1/kUAcqLCxGtGta0WPrKjA== based on the resources that are available and local expert concern about missing serious concomitant intra-abdominal consensus opinion to apply the safest, most reliable manage- injuries.11–13 However, with increasing experience with NOM, ment strategies for their patients. What works at one institu- recognition that negative laparotomies caused significant tion may not work at another. -

Left Flank Pain As the Sole Manifestation of Acute Pancreatitis

452 CASE REPORTS Emerg Med J: first published as 10.1136/emj.2003.013847 on 23 May 2005. Downloaded from Left flank pain as the sole manifestation of acute pancreatitis: a report of a case with an initial misdiagnosis J-H Chen, C-H Chern, J-D Chen, C-K How, L-M Wang, C-H Lee ............................................................................................................................... Emerg Med J 2005;22:452–453 On further review of the patient’s case 2 hours after the Acute pancreatitis is not an uncommon disease in an ultrasound examination, a decision was made to obtain a emergency department (ED). It manifests as upper abdominal computed tomography (CT) scan due to concern over the pain, sometimes with radiation of pain to the back and flank limitation of ultrasound studies in some clinical conditions. region. Isolated left flank pain being the sole manifestation of The CT showed abnormal fluid collection over the peri-renal acute pancreatitis is very rare and not previously identified in space and pancreatic tail as well as necrotic changes and the literature. In this report, we present a case of acute swelling of the pancreatic tail (fig 1). Serum pancreatic pancreatitis presenting solely with left flank pain. Having enzymes revealed a normal amylase (90 u/L) and a slightly negative findings on an ultrasound initially, she was elevated lipase level (336 u/L). The patient was diagnosed to misdiagnosed as having possible ‘‘acute pyelonephritis or have acute pancreatitis and admitted for supportive treat- other renal diseases’’. A second radiographic evaluation ment and monitoring. During her admission she was also with computed tomography showed pancreatitis in the tail noted to have hyperlipidemia (triglyceride 980 mg/dL and with abnormal fluid collected extending to the left peri-renal cholesterol 319 mg/dL). -

Surgical Compared with Nonsurgical Management of Fractures in Male Veterans with Chronic Spinal Cord Injury

Spinal Cord (2015) 53, 402–407 & 2015 International Spinal Cord Society All rights reserved 1362-4393/15 www.nature.com/sc ORIGINAL ARTICLE Surgical compared with nonsurgical management of fractures in male veterans with chronic spinal cord injury M Bethel1,2, L Bailey3,4, F Weaver3,5,BLe1,2, SP Burns6,7, JN Svircev6,7, MH Heggeness8,9 and LD Carbone1,2 Study design: Retrospective review of a clinical database. Objectives: To examine treatment modalities of incident appendicular fractures in men with chronic SCI and mortality outcomes by treatment modality. Setting: United States Veterans Health Administration Healthcare System. Methods: This was an observational study of 1979 incident fractures that occurred over 6 years among 12 162 male veterans with traumatic SCI of at least 2 years duration from the Veterans Health Administration (VA) Spinal Cord Dysfunction Registry. Treatment modalities were classified as surgical or nonsurgical treatment. Mortality outcomes at 1 year following the incident fracture were determined by treatment modality. Results: A total of 1281 male veterans with 1979 incident fractures met inclusion criteria for the study. These fractures included 345 (17.4%) upper-extremity fractures and 1634 (82.6%) lower-extremity fractures. A minority of patients (9.4%) were treated with surgery. Amputations and disarticulations accounted for 19.7% of all surgeries (1.3% of all fractures), and the majority of these were done more than 6 weeks following the incident fracture. There were no significant differences in mortality among men with fractures treated surgically compared with those treated nonsurgically. Conclusions: Currently, the majority of appendicular fractures in male patients with chronic SCI are managed nonsurgically within the VA health-care system. -

Delayed Complications of Nonoperative Management of Blunt Adult Splenic Trauma

PAPER Delayed Complications of Nonoperative Management of Blunt Adult Splenic Trauma Christine S. Cocanour, MD; Frederick A. Moore, MD; Drue N. Ware, MD; Robert G. Marvin, MD; J. Michael Clark, BS; James H. Duke, MD Objective: To determine the incidence and type of de- Results: Patients managed nonoperatively had a sig- layed complications from nonoperative management of nificantly lower Injury Severity Score (P<.05) than adult splenic injury. patients treated operatively. Length of stay was signifi- cantly decreased in both the number of intensive care Design: Retrospective medical record review. unit days as well as total length of stay (P<.05). The number of units of blood transfused was also signifi- Setting: University teaching hospital, level I trauma center. cantly decreased in patients managed nonoperatively (P<.05). Seven patients (8%) managed nonoperatively Patients: Two hundred eighty patients were admitted developed delayed complications requiring interven- to the adult trauma service with blunt splenic injury dur- tion. Five patients had overt bleeding that occurred at ing a 4-year period. Men constituted 66% of the popu- 4 days (3 patients), 6 days (1 patient), and 8 days (1 lation. The mean (±SEM) age was 32.2±1.0 years and the patient) after injury. Three patients underwent sple- mean (±SEM) Injury Severity Score was 22.8±0.9. Fifty- nectomy, 1 had a splenic artery pseudoaneurysm nine patients (21%) died of multiple injuries within 48 embolization, and 1 had 2 areas of bleeding emboliza- hours and were eliminated from the study. One hun- tion. Two patients developed splenic abscesses at dred thirty-four patients (48%) were treated operatively approximately 1 month after injury; both were treated within the first 48 hours after injury and 87 patients (31%) by splenectomy.