Not My Problem!(?): Jewish Transgressors and the Limits of Communal Responsibility

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Foreword, Abbreviations, Glossary

FOREWORD, ABBREVIATIONS, GLOSSARY The Soncino Babylonian Talmud TRANSLATED INTO ENGLISH WITH NOTES Reformatted by Reuven Brauner, Raanana 5771 1 FOREWORDS, ABBREVIATIONS, GLOSSARY Halakhah.com Presents the Contents of the Soncino Babylonian Talmud TRANSLATED INTO ENGLISH WITH NOTES, GLOSSARY AND INDICES UNDER THE EDITORSHIP OF R AB B I D R . I. EPSTEIN B.A., Ph.D., D. Lit. FOREWORD BY THE VERY REV. THE LATE CHIEF RABBI DR. J. H. HERTZ INTRODUCTION BY THE EDITOR THE SONCINO PRESS LONDON Original footnotes renumbered. 2 FOREWORDS, ABBREVIATIONS, GLOSSARY These are the Sedarim ("orders", or major There are about 12,800 printed pages in the divisions) and tractates (books) of the Soncino Talmud, not counting introductions, Babylonian Talmud, as translated and indexes, glossaries, etc. Of these, this site has organized for publication by the Soncino about 8050 pages on line, comprising about Press in 1935 - 1948. 1460 files — about 63% of the Soncino Talmud. This should in no way be considered The English terms in italics are taken from a substitute for the printed edition, with the the Introductions in the respective Soncino complete text, fully cross-referenced volumes. A summary of the contents of each footnotes, a master index, an index for each Tractate is given in the Introduction to the tractate, scriptural index, rabbinical index, Seder, and a detailed summary by chapter is and so on. given in the Introduction to the Tractate. SEDER ZERA‘IM (Seeds : 11 tractates) Introduction to Seder Zera‘im — Rabbi Dr. I Epstein INDEX Foreword — The Very Rev. The Chief Rabbi Israel Brodie Abbreviations Glossary 1. -

May 2020 Newsletter

1836 Rohrerstown Road Lancaster, PA 17601 [email protected] 717-581-7891 www.tbelancaster.org Volume 72, No. 8 Omer - Sivan 5780 MAY 2020 Mission Statement Attn: Temple Beth El Members and Friends The mission of Temple Beth El is to provide a house of Conservative The Temple Beth El Monthly Bulletin will now be available electronically every Jewish worship which fosters month. Where? spiritual fulfillment, Jewish theology, • On the TBE website under the Welcome tab life-long Jewish education, and • Via direct email to you each month community support throughout the • Via a link in every Tuesday Mail Chimp e-news cycles of the seasons. At Temple Beth El, we are always trying to optimize our cost savings while Board of Directors enhancing our offerings to you. As you may know, we no longer do bulk President - Gary Kogon mailings and the Bulletin printing and mailing costs are continuing to escalate. Vice President - Steve Gordon We also want to introduce more color, and provide links to other articles of Secretary - Hal Koplin interest. Treasurer - Samantha Besnoff One way to do this is make the monthly Bulletin mailing optional, while posting Financial Secretary - Linda Hutt it electronically to our website. The bulletin will also be available in Directors: Lynn Brooks, Bob Brosbe, downloadable PDF format on the Temple Beth El website (tbelancaster.org), in Abshalom Cooper, Sue Friedman, our weekly Mail Chimp email, and via your direct email address, to read online Yitzie Gans, Ilana Huber, Dolly and for those who wish to print their own hard copy. Shuster Earl Stein, Ruth Wunderlich. -

Torah in Triclinia: the Rabbinic Banquet and the Significance of Architecture

Theological Studies Faculty Works Theological Studies 2012 Torah in triclinia: the Rabbinic Banquet and the Significance of Architecture Gil P. Klein Loyola Marymount University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lmu.edu/theo_fac Part of the Religion Commons Recommended Citation Klein, Gil P. "Torah in Triclinia: The Rabbinic Banquet and the Significance of Architecture." Jewish Quarterly Review, vol. 102 no. 3, 2012, p. 325-370. doi:10.1353/jqr.2012.0024. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Theological Studies at Digital Commons @ Loyola Marymount University and Loyola Law School. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theological Studies Faculty Works by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons@Loyola Marymount University and Loyola Law School. For more information, please contact [email protected]. T HE J EWISH Q UARTERLY R EVIEW, Vol. 102, No. 3 (Summer 2012) 325–370 Torah in Triclinia: The Rabbinic Banquet and the Significance of Architecture GIL P. KLEIN INASATIRICALMOMENTin Plato’s Symposium (175a), Socrates, who ARTICLES is expected at the banquet, disappears, only to be found lost in thought on the porch of a neighboring house. Similarly, in the Palestinian Talmud (yBer 5.1, 9a), Resh Lakish appears so immersed in thought about the Torah that he unintentionally crosses the city’s Sabbath boundary. This shared trope of the wise man whose introspection leads to spatial disori- entation is not surprising.1 Different as the Platonic philosopher may be -

Demai for the Poor

בס"ד Volume 13. Issue 11 Demai for the Poor The Mishnah (3:1) teaches that one is able to feed that the Rambam explained the leniency was motivated demai produce to the poor. In other words, the to ease the mitzvah of tzedaka. Consequently, the requirement of separating terumot and maasrot from leniency is only afforded to the ani in that context - demai produce is lifted for an ani (poor person). The when one feeds an ani. If, however the ani receives a Mishnah continues that this leniency was also afforded good portion as part of a tzedaka distribution and takes to the achsanya. The Bartenura explains that this refers it home, then he is obligated to separate Demai. He to Jewish soldiers that passed through from town to explains that that is why the Mishnah used to word town. By force of law, the people of each town were “ma’achilin” (feed) and not “ochlin” (eat) when made responsible to feed them. Why are these people teaching this exemption, since it is only in the context excluded from the gezeirah of demai? of feeding the ani that he is exempt. This would also explain why the Mishnah only records the requirement Rashi (Eiruvin 17b) explains that whether or not one is of informing the ani in the case of a tzedaka truly required to separate terumot and maasrot from distribution but not in the case of feeding aniim demai. demai is doubtful – it is a safek. Furthermore, most Amei Haaretz separated everything that was required The Tosfot Yom Tov, however notes that the Rambam anyway. -

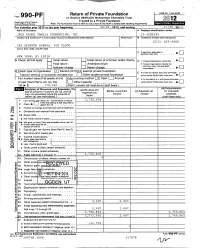

Return of Private Foundation

Return of Private Foundation OMB No 1545 -0052 Fonn 990 -PFI or Section 4947( a)(1) Nonexempt Charitable Trust Treated as a Private Foundation 2012 Department of the Treasury Internal Revenue Sennce Note The foundation may be able to use a copy of this return to satisfy state reporting requirements For calendar year 2012 or tax year beginning 12/01 , 2012 , and endii 11/30. 2013 Name of foundation A Employer identification number JACK ADJMT FAMILY FOUNDATION. INC. 13-3202295 Number and street ( or P 0 box number If mail is not delivered to street address ) Room/suite B Telephone number ( see instructions) (212) 629-9600 463 SEVENTH AVENUE, 4TH FLOOR City or town, state , and ZIP code C If exemption application is , q pending , check here . NEW YORK, NY 10018 G Check all that apply: Initial return Initial return of a former public charity D 1 Foreign organ izations . check here El Final return Amended return 2 Foreign organizations meeting the 85% test, check here and attach Address change Name chang e computation . • • • • • • . H Check type of organization X Section 501 ( cJ 3 exempt private foundation E If private foundation status was terminated Section 4947 ( a )( 1 nonexem pt charitable trust Other taxable p rivate foundation under section 507(bxlXA ), check here . Ill. El I Fair market value of all assets at end J Accountin g method X Cash L_J Accrual F If the foundation is in a 60-month termination of year (from Part Il, col. (c), line 0 Other ( specify) _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ under section 507(b )( 1)(B), check here 16) 10- $ 17 0 , 2 4 0 . -

Torah Jewry "Down Under" New Morality - How New Is It? the JEWISH OBSERVER

ELUL 5728 / SEPTEMBER 1968 VOLUME 5, NUMBER 4 rHE FIFTY CENTS The Rising Cost of Life Torah Jewry "Down Under" New Morality - How New Is It? THE JEWISH OBSERVER In this issue ... THE RELEVANCE OF SANCTITY. Chaim Keller .................................... 3 ORTHODOXY IN AUSTRALIA, Shmuel Gorr ............................................. 8 THE NEGRO AND THE ORTHODOX JEW, Bernard Weinberger 11 THE RISING CosT OF LIFE, Yisroel Mayer Kirzner ........................ 15 THE JEWISH OBSERVER is published monthly, except July and Aug~st, by the Agudath Israel of America, DR. FALK SCHLESINGER, n,,~~ i'"lt ,,T ............................................... 18 5 Beekman Stret, New York, N. Y. 10038 Second class postage paid at New York, N. Y. THE SUPREME COURT TEXTBOOK DECISION, Judah Dick......... 19 Subscription: $5.00 per :year; Canada and overseas: $6.00; single copy: 50t. Printed in the U.S.A. THE Loss OF EUROPE'S ToRAH CENTERS: A LEssoN FoR OuR GENERATION ................................................................................ 22 Editorial Board DR. ERNEST L. BODENHEI~!ER Chairman SECOND LOOKS AT THE JEWISH SCENE: RABBI NATHAN BULMAN Jews Without a Press.......................................................................... 26 RABBI JOSEPH ELIAS JOSEPH FRIEDENSON RABBI MoSHE SHERER A PERSONAL NOTE .. ..... ............. ......................................................................... 29 Advertising Manager "RABBI SYSHE HESCHEL Managing Editor RABBI YAAKOV JACOBS THE JEWISH OBSERVER does not assume responsibility for t_he -

Chapter 2 Tort Liability in Maimonides

CHAPTER 2 TORT LIABILITY IN MAIMONIDES’ CODE (MISHNEH TORAH): THE DOWNSIDE OF THE COMMON INTERPRETATION A. INTRODUCTION: THE MODERN STUDY OF JEWISH TORT THEORY AS A STORY OF “SELF- MIRRORING” B. THE OWNERSHIP AND STRICT LIABILITY THEORY VS. THE FAULT-BASED THEORY (PESHIAH) (1) The Difficulties of the Concept of Peshiah (2) The Common Interpretation of the Code: The “Ownership and Strict Liability Theory” C. EXEGETICAL AND CONCEPTUAL DIFFICULTIES OF THE COMMON INTERPRETATION OF MAIMONIDES (1) Maimonides did not Impose Comprehensive Strict Liability on the Tortfeasor (2) Maimonides’ Use of the Term Peshiah in Different Places (3) The Theory of Ownership Contradicts Various Rulings in the Code (4) The Problem with Finding a Convincing Rationale for the Ownership Theory D. DIFFICULTIES IN UNDERSTANDING SOME ELEMENTS OF TORT LIABILITY MENTIONED IN THE CODE (1) Rulings that are Difficult to Interpret according to Either Ownership or Fault-Based Theories (2) Providing a Rationale for the Exemption in Tort (3) Standard of Care in Damages Caused by a Person to the Property of Another: Absolute/Strict Liability or Negligence? (4) Deterrence of Risk-Causing Behavior E. RE-EXAMINING THE OPENING CHAPTER OF THE BOOK OF TORTS IN THE CODE: CONTROL AS A CENTRAL ELEMENT OF LIABILITY IN TORT F. CONCLUSION 1 A. INTRODUCTION: THE MODERN STUDY OF JEWISH TORT THEORY AS A STORY OF “SELF- MIRRORING” Isidore Twersky showed us that “[t]o a great extent the study of Maimonides is a story of ‘self- mirroring’,”1 and that the answers given by modern and medieval scholars and rabbis to some questions on the concepts of Maimonides “were as different as their evaluations of Maimonides, tempered of course by their own ideological convictions and/or related contingencies.”2 Maimonides’ opening passages of the Book of Torts (Sefer Nezikin) in the Code (Mishneh Torah) can also be described as a story of “self-mirroring”. -

Alabama Arizona Arkansas California

ALABAMA ARKANSAS N. E. Miles Jewish Day School Hebrew Academy of Arkansas 4000 Montclair Road 11905 Fairview Road Birmingham, AL 35213 Little Rock, AR 72212 ARIZONA CALIFORNIA East Valley JCC Day School Abraham Joshua Heschel 908 N Alma School Road Day School Chandler, AZ 85224 17701 Devonshire Street Northridge, CA 91325 Pardes Jewish Day School 3916 East Paradise Lane Adat Ari El Day School Phoenix, AZ 85032 12020 Burbank Blvd. Valley Village, CA 91607 Phoenix Hebrew Academy 515 East Bethany Home Road Bais Chaya Mushka Phoenix, AZ 85012 9051 West Pico Blvd. Los Angeles, CA 90035 Shalom Montessori at McCormick Ranch Bais Menachem Yeshiva 7300 N. Via Paseo del Sur Day School Scottsdale, AZ 85258 834 28th Avenue San Francisco, CA 94121 Shearim Torah High School for Girls Bais Yaakov School for Girls 6516 N. Seventh Street, #105 7353 Beverly Blvd. Phoenix, AZ 85014 Los Angeles, CA 90035 Torah Day School of Phoenix Beth Hillel Day School 1118 Glendale Avenue 12326 Riverside Drive Phoenix, AZ 85021 Valley Village, CA 91607 Tucson Hebrew Academy Bnos Devorah High School 3888 East River Road 461 North La Brea Avenue Tucson, AZ 85718 Los Angeles, CA 90036 Yeshiva High School of Arizona Bnos Esther 727 East Glendale Avenue 116 N. LaBrea Avenue Phoenix, AZ 85020 Los Angeles, CA 90036 Participating Schools in the 2013-2014 U.S. Census of Jewish Day Schools Brandeis Hillel Day School Harkham Hillel Hebrew Academy 655 Brotherhood Way 9120 West Olympic Blvd. San Francisco, CA 94132 Beverly Hills, CA 90212 Brawerman Elementary Schools Hebrew Academy of Wilshire Blvd. Temple 14401 Willow Lane 11661 W. -

The Jewish Observer

··~1 .··· ."SH El ROT LEUMI''-/ · .·_ . .. · / ..· .:..· 'fo "ABSORPTION" •. · . > . .· .. ·· . NATIONALSERVICE ~ ~. · OF SOVIET. · ••.· . ))%, .. .. .. · . FOR WOMEN . < ::_:··_---~ ...... · :~ ;,·:···~ i/:.)\\.·:: .· SECOND LOOKS: · · THE BATil.E · . >) .·: UNAUTHORIZED · ·· ·~·· "- .. OVER CONTROL AUTOPSIES · · · OF THE RABBlNATE . THE JEWISH OBSERVER in this issue ... DISPLACED GLORY, Nissan Wo/pin ............................................................ 3 "'rELL ME, RABBI BUTRASHVILLI .. ,"Dov Goldstein, trans lation by Mirian1 Margoshes 5 So~rn THOUGHTS FROM THE ROSHEI YESHIVA 8 THE RABBINATE AT BAY, David Meyers................................................ 10 VOLUNTARY SERVICE FOR WOMEN: COMPROMISE OF A NATION'S PURITY, Ezriel Toshavi ..... 19 SECOND LOOKS RESIGNATION REQUESTED ............................................................... 25 THE JEWISH OBSERVER is published monthly, except July and August, by the Agudath Israel of America, 5 Beekman Street, New York, New York 10038. Second class postage paid at New York, N. Y. Subscription: $5.00 per year; Two years, $8.50; Three years, $12.00; outside of the United States, $6.00 per year. Single copy, fifty cents. SPECIAL OFFER! Printed in the U.S.A. RABBI N ISSON W OLPJN THE JEWISH OBSERVER Editor 5 Beekman Street 7 New York, N. Y. 10038 Editorial Board D NEW SUBSCRIPTION: $5 - 1 year of J.O. DR. ERNEST L. BODENHEIMER Plus $3 • GaHery of Portraits of Gedolei Yisroel: FREE! Chairman RABBI NATHAN BULMAN D RENEWAL: $12 for 3 years of J.0. RABBI JOSEPH ELIAS Plus $3 - Gallery of Portraits of Gedo lei Yisroel: FREE! JOSEPH FRIEDENSON D GIFT: $5 - 1 year; $8.50, 2 yrs.; $12, 3 yrs. of ].0. RABBI YAACOV JACOBS Plus $3 ·Gallery of Portraits of Gedolei Yisroel: FREE! RABBI MOSHE SHERER Send '/Jf agazine to: Send Portraits to: THE JEWISH OBSERVER does not iVarne .... -

JCT Develops Solutions to Environmental Problems P.O.BOX 16031, JERUSALEM 91160 ISRAEL 91160 JERUSALEM 16031, P.O.BOX

NISSAN 5768 / APRIL 2008, VOL. 13 Green and Clean JCT Develops Solutions to Environmental Problems P.O.BOX 16031, JERUSALEM 91160 ISRAEL 91160 JERUSALEM 16031, P.O.BOX NISSAN 5768 / APRIL 2008, VOL. 13 Green and Clean JCT Develops Solutions to Environmental Problems P.O.BOX 16031, JERUSALEM 91160 ISRAEL 91160 JERUSALEM 16031, P.O.BOX COMMENTARY JERUSALEM COLLEGE OF TECHNOLOGY PRESIDENT Shalom! opportunity to receive an excellent education Prof. Joseph S. Bodenheimer allowing them to become highly-skilled, ROSH HAYESHIVA Rabbi Z. N. Goldberg Of the many things sought after professionals. More important ROSH BEIT HAMIDRASH we are proud at JCT, for our students is the opportunity available Rabbi Natan Bar Chaim nothing is more RECTOR at the College to receive an education Prof. Joseph M. Steiner prized than our focusing on Jewish values. It is this DIRECTOR-GENERAL students. In every education towards values that has always Dr. Shimon Weiss VICE PRESIDENT FOR DEVELOPMENT issue of “Perspective” been the hallmark of JCT and it is this AND EXTERNAL AFFAIRS we profile one of our students as a way of commitment to Jewish ethical values that Reuven Surkis showing who they are and of sharing their forms the foundation from which Israeli accomplishments with you. society will grow and flourish - and our EDITORS Our student body of 2,500 is a students and graduates take pride in being Rosalind Elbaum, Debbie Ross, Penina Pfeuffer microcosm of Israeli society: 21% are Olim committed to this process. DESIGN & PRODUCTION (immigrants) from the former Soviet Union, As we approach the Pesach holiday, the Studio Fisher Ethiopia, South America, North America, 60th anniversary of the State of Israel and JCT Perspective invites the submission of arti- Europe, Australia and South Africa, whilst the 40th anniversary of JCT, let us reaffirm cles and press releases from the public. -

Gender in Jewish Studies

Gender in Jewish Studies Proceedings of the Sherman Conversations 2017 Volume 13 (2019) GUEST EDITOR Katja Stuerzenhofecker & Renate Smithuis ASSISTANT EDITOR Lawrence Rabone A publication of the Centre for Jewish Studies, University of Manchester, United Kingdom. Co-published by © University of Manchester, UK. All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. No part of this volume may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publisher, the University of Manchester, and the co-publisher, Gorgias Press LLC. All inquiries should be addressed to the Centre for Jewish Studies, University of Manchester (email: [email protected]). Co-Published by Gorgias Press LLC 954 River Road Piscataway, NJ 08854 USA Internet: www.gorgiaspress.com Email: [email protected] ISBN 978-1-4632-4056-1 ISSN 1759-1953 This volume is printed on acid-free paper that meets the American National Standard for Permanence of paper for Printed Library Materials. Printed in the United States of America Melilah: Manchester Journal of Jewish Studies is distributed electronically free of charge at www.melilahjournal.org Melilah is an interdisciplinary Open Access journal available in both electronic and book form concerned with Jewish law, history, literature, religion, culture and thought in the ancient, medieval and modern eras. Melilah: A Volume of Studies was founded by Edward Robertson and Meir Wallenstein, and published (in Hebrew) by Manchester University Press from 1944 to 1955. Five substantial volumes were produced before the series was discontinued; these are now available online. -

Nitzotzot Min Haner Volume #16 January – March 2004 -- Page # 2

NNiittzzoottzzoott MMiinn HHaaNNeerr VVoolluummee ##1166,, JJaannuuaarryy –– MMaarrcchh 22000044 Table of Contents INTRODUCTION AND OVERVIEW 2 MYSTERIOUS APPEARANCE OF THE COMMUNITY KOLLEL IDEA 3 MODELS 8 THE KOLLEL AS AN OUTREACH ORGANIZATION 10 HALACHIC STANDARDS 13 THE KOLLEL AS A CATALYST FOR OTHER INSTITUTIONS IN THE CITY 15 THE KOLLEL AS A SPRINGBOARD FOR NEW MANPOWER IN THE COMMUNITY 16 THE KIRUV CONTRIBUTION OF THE LAKEWOOD-TYPE COMMUNITY KOLLEL 18 THE PERCEPTION OF KOLLEL FAMILIES BY THE COMMUNITY 20 WHY KOLLELS FAILED? 21 IS A KOLLEL ALWAYS GOOD FOR A TOWN? 22 HOW TO START A NEW KOLLEL 25 FINANCES 25 SIZE 26 KOLLEL SALARIES 26 LOCAL INTEREST AND SUPPORT 26 COMMUNITY OR OUTREACH MODEL 27 SELECTION OF THE ROSH CHABURA 27 SELECTION OF THE AVREICHIM 28 ADVANCE GUARD AND WELCOMING COMMITTEE 30 Appendices APPENDIX A: WHAT SHOULD BE CALLED A KOLLEL? 32 APPENDIX B: THE TORAH STUDY OF THE AVREICHIM 33 APPENDIX C: THE CHICAGO COMMUNITY KOLLEL - LIST OF ALUMNI 35 Nitzotzot Min HaNer Volume #16 January – March 2004 -- Page # 2 Introduction and Overview A Jewish man without torah knowledge Is a man divorced from his glorious past; A Jewish city without halls of torah study Is a city estranged from its glorious future. Rabbi Zev Epstein1 on the idea of a kollel In every way Kollel rabbis are ambassadors of Torah … A Rav without a defined kehilla … A bridge so to speak to the Torah world Rabbi Zvi Holland, Phoenix Community Kollel In this edition, Nitzotzot has undertaken a discussion of the central institution in the development of Torah life around the world, the community or outreach kollel.