A Situational Analysis of the Nba and Diminishing Player Autonomy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Oh My God, It's Full of Data–A Biased & Incomplete

Oh my god, it's full of data! A biased & incomplete introduction to visualization Bastian Rieck Dramatis personæ Source: Viktor Hertz, Jacob Atienza What is visualization? “Computer-based visualization systems provide visual representations of datasets intended to help people carry out some task better.” — Tamara Munzner, Visualization Design and Analysis: Abstractions, Principles, and Methods Why is visualization useful? Anscombe’s quartet I II III IV x y x y x y x y 10.0 8.04 10.0 9.14 10.0 7.46 8.0 6.58 8.0 6.95 8.0 8.14 8.0 6.77 8.0 5.76 13.0 7.58 13.0 8.74 13.0 12.74 8.0 7.71 9.0 8.81 9.0 8.77 9.0 7.11 8.0 8.84 11.0 8.33 11.0 9.26 11.0 7.81 8.0 8.47 14.0 9.96 14.0 8.10 14.0 8.84 8.0 7.04 6.0 7.24 6.0 6.13 6.0 6.08 8.0 5.25 4.0 4.26 4.0 3.10 4.0 5.39 19.0 12.50 12.0 10.84 12.0 9.13 12.0 8.15 8.0 5.56 7.0 4.82 7.0 7.26 7.0 6.42 8.0 7.91 5.0 5.68 5.0 4.74 5.0 5.73 8.0 6.89 From the viewpoint of statistics x y Mean 9 7.50 Variance 11 4.127 Correlation 0.816 Linear regression line y = 3:00 + 0:500x From the viewpoint of visualization 12 12 10 10 8 8 6 6 4 4 4 6 8 10 12 14 16 18 4 6 8 10 12 14 16 18 12 12 10 10 8 8 6 6 4 4 4 6 8 10 12 14 16 18 4 6 8 10 12 14 16 18 How does it work? Parallel coordinates Tabular data (e.g. -

COWBOY COACHES Head Coach

COWBOY COACHES Head Coach Outlook Coaches Cowboys Opponents STEVE McCLAIN Review Records HEAD BASKETBALL COACH Traditions (Chadron State ‘84) Staff MWC teve McClain enters his First Team All-Mountain West Conference: Josh Davis (1999-2000 ninth season as head and 2000-01); Marcus Bailey (2000-01 and 2001-02); Uche Nsonwu- Scoach at the University of Amadi (2002-03); Donta Richardson (2002-03) and Jay Straight Wyoming. In his eight previous (2004-05). seasons at Wyoming, McClain The high point of the Cowboys’ return to national prominence was has led Wyoming Basketball Wyoming’s appearance in the 2002 NCAA Tournament. It marked the through one of its most school’s fi rst appearance since 1988. Wyoming’s fi rst round win over successful periods in school No. 6 ranked Gonzaga, 73-66, on March 14, 2002, was Wyoming’s fi rst history. When you begin to list NCAA Tournament win since March 14, 1987, when UW defeated No. the accomplishments over the 4 ranked UCLA, 78-68. With their fi rst round win in the 2002 NCAA past eight seasons, one begins Tournament, the Pokes ended the season among the Top 32 teams in to realize how far the Cowboy the country. For his outstanding coaching, McClain was selected the Basketball program has come. 2001-02 MWC Coach of the Year by his fellow coaches. In four of the last eight In the 2000-01 season, he earned Mountain West Conference seasons, Wyoming has appeared in postseason play. The Pokes Coach of the Year honors from CollegeInsider.com, and earned the advanced to the Second Round of the 2002 NCAA Tournament and same honor from MWC media members for the 1999-2000 season. -

Probable Starters

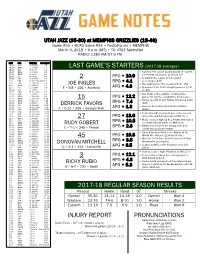

UTAH JAZZ (35-30) at MEMPHIS GRIZZLIES (18-46) Game #66 • ROAD Game #34 • FedExForum • MEMPHIS March 9, 2018 • 6 p.m. (MT) • TV: AT&T SportsNet RADIO: 1280 AM/97.5 FM DATE OPP. TIME (MT) RECORD/TV 10/18 DEN W, 106-96 1-0 10/20 @MIN L, 97-100 1-1 LAST GAME’S STARTERS (2017-18 averages) 10/21 OKC W, 96-87 2-1 10/24 @LAC L, 84-102 2-2 • Notched first career double-double (11 points, 10/25 @PHX L, 88-97 2-3 career-high 10 assists) at IND on 3/7 10/28 LAL W, 96-81 3-3 PPG • 10.9 10/30 DAL W, 104-89 4-3 2 • Second in the league in three-point 11/1 POR W, 112-103 (OT) 5-3 RPG • 4.1 percentage (.445) 11/3 TOR L, 100-109 5-4 JOE INGLES • Has eight games this season with 5+ 3FG 11/5 @HOU L, 110-137 5-5 11/7 PHI L, 97-104 5-6 F • 6-8 • 226 • Australia APG • 4.3 • Appeared in his 200th straight game on 2/24 11/10 MIA L, 74-84 5-7 vs. DAL 11/11 BKN W, 114-106 6-7 11/13 MIN L, 98-109 6-8 • Has made a three-pointer in consecutive 11/15 @NYK L, 101-106 6-9 PPG • 12.2 games for just the second time in his career 11/17 @BKN L, 107-118 6-10 15 11/18 @ORL W, 125-85 7-10 RPG • 7.4 • Ranks seventh in Jazz history in blocked shots 11/20 @PHI L, 86-107 7-11 DERRICK FAVORS (641) 11/22 CHI W, 110-80 8-11 Jazz are 11-3 when he records a double- 11/25 MIL W, 121-108 9-11 • APG • 1.3 11/28 DEN W, 106-77 10-11 F • 6-10 • 265 • Georgia Tech double 11/30 @LAC W, 126-107 11-11 st 12/1 NOP W, 114-108 12-11 • Posted his 21 double-double of the season 12/4 WAS W, 116-69 13-11 27 PPG • 13.6 (23 points and 14 rebounds) at IND (3/7) 12/5 @OKC L, 94-100 13-12 • Made a career-high 12 free throws and scored 12/7 HOU L, 101-112 13-13 RPG • 10.5 12/9 @MIL L, 100-117 13-14 RUDY GOBERT a season-high 26 points vs. -

65 Orlando Magic Magazine Photo Frames (Green Tagged and Numbered)

65 Orlando Magic Magazine Photo Frames (Green Tagged and Numbered) 1. April 1990 “Stars Soar Into Orlando” 2. May 1990 “Ice Gets Hot” 3. May 1990 “The Rookies” 4. June 1990 Magic Dancers “Trying Tryouts” 5. October 1990 “Young Guns III” 6. December 1990 Greg Kite “BMOC” 7. January 1991 “Battle Plans” 8. February 1991 “Cat Man Do” 9. April 1991 “Final Exam” 10. May 1991 Dennis Scott “Free With The Press” 11. June 1991 Scott Skiles “A Star on the Rise” 12. October 1991 “Brian Williams: Renaissance Man” 13. December 1991 “Full Court Press” 14. January 1992 Scott Skiles “The Fitness Team” 15. February 1992 TV Media “On The Air” 16. All-Star Weekend 1992 “Orlando All Star” 17. March 1992 Magic Johnson “Magic Memories” 18. April 1992 “Star Search” 19. June 1992 Shaq “Shaq, Rattle and Roll” 20. October 1992 Shaq “It’s Shaq Time” (Autographed) 21. December 1992 Shaq “Reaching Out” 22. January 1993 Nick Anderson “Flying in Style” 23. May 1993 Shaq “A Season to Remember” 24. Summer 1993 Shaq “The Shaq Era” 25. November 1993 Shaq “Great Expectations” 26. December 1993 Scott Skiles “Leader of the Pack” 27. January 1994 Larry Krystkowiak “Big Guy From Big Sky” 28. February 1994 Anthony Bowie “The Energizer” 29. March 1994 Anthony Avant “Avant’s New Adventure” 30. June 1994 Shaq “Ouch” 31. July 1994 Dennis Scott “The Comeback Kid” 32. August 1994 Shaq “Shaq’s Dream World” 33. September 1994 “Universal Appeal” 34. October 1994 Horace Grant “Orlando’s Newest All-Star” 35. November 1994 “The New Fab Five” 36. -

Set Info - Player - National Treasures Basketball

Set Info - Player - National Treasures Basketball Player Total # Total # Total # Total # Total # Autos + Cards Base Autos Memorabilia Memorabilia Luka Doncic 1112 0 145 630 337 Joe Dumars 1101 0 460 441 200 Grant Hill 1030 0 560 220 250 Nikola Jokic 998 154 420 236 188 Elie Okobo 982 0 140 630 212 Karl-Anthony Towns 980 154 0 752 74 Marvin Bagley III 977 0 10 630 337 Kevin Knox 977 0 10 630 337 Deandre Ayton 977 0 10 630 337 Trae Young 977 0 10 630 337 Collin Sexton 967 0 0 630 337 Anthony Davis 892 154 112 626 0 Damian Lillard 885 154 186 471 74 Dominique Wilkins 856 0 230 550 76 Jaren Jackson Jr. 847 0 5 630 212 Toni Kukoc 847 0 420 235 192 Kyrie Irving 846 154 146 472 74 Jalen Brunson 842 0 0 630 212 Landry Shamet 842 0 0 630 212 Shai Gilgeous- 842 0 0 630 212 Alexander Mikal Bridges 842 0 0 630 212 Wendell Carter Jr. 842 0 0 630 212 Hamidou Diallo 842 0 0 630 212 Kevin Huerter 842 0 0 630 212 Omari Spellman 842 0 0 630 212 Donte DiVincenzo 842 0 0 630 212 Lonnie Walker IV 842 0 0 630 212 Josh Okogie 842 0 0 630 212 Mo Bamba 842 0 0 630 212 Chandler Hutchison 842 0 0 630 212 Jerome Robinson 842 0 0 630 212 Michael Porter Jr. 842 0 0 630 212 Troy Brown Jr. 842 0 0 630 212 Joel Embiid 826 154 0 596 76 Grayson Allen 826 0 0 614 212 LaMarcus Aldridge 825 154 0 471 200 LeBron James 816 154 0 662 0 Andrew Wiggins 795 154 140 376 125 Giannis 789 154 90 472 73 Antetokounmpo Kevin Durant 784 154 122 478 30 Ben Simmons 781 154 0 627 0 Jason Kidd 776 0 370 330 76 Robert Parish 767 0 140 552 75 Player Total # Total # Total # Total # Total # Autos -

UCLA Men's Basketball Dec. 14, 2002 Marc Dellins/Bill Bennett/310-206

UCLA Men’s Basketball Dec. 14, 2002 Marc Dellins/Bill Bennett/310-206-8179 For Immediate Release IT'S FINALS WEEK FOR UCLA AS THE BRUINS HOST PORTLAND ON SATURDAY, DEC. 14 (5 P.M.) IN PAULEY PAVILION; UCLA WINS FIRST GAME OF SEASON ON DEC. 8 IN PAULEY, BEATING LONG BEACH STATE, 81-58 78.3(18-23) from the foul line, with 21 rebounds and 15 UPCOMING GAME turnovers. The 49ers were led by Tony Darden's 14 points. The Bruins lead the Long Beach State series 9-0. SATURDAY, DEC. 14 – UCLA (1-2) v s . Portland (3-2), 5 p.m., Pauley Pavilion. TV - UCLA-Portland Series – UCLA leads it 2-0. The Fox Sports Net West 2, with Bill Bruins have won both games in Pauley – 93-69 in 1967-68 Macdonald/Dan Belluomini; Radio – Fox Sports and 122-57 in 1966-67. AM 1150 – Chris Roberts/Don MacLean). UCLA TENTATIVE STARTING LINEUP (1-2) PORTLAND STARTING LINEUP (3-2) No. Name Pos. Ht. C l . Ppg Rpg No. Name Pos. Ht. Cl. Ppg Rpg 24 Jason Kapono F 6-8 Sr. 21.3 7.3 44 Dustin Geddis F 6-7 Jr. 8.0 6.0 43 T. J. Cummings C 6-10 Jr. 8.7 4.0 14 Ghislain Sema C 6-7 Jr. 7.6 5.2 45 Michael Fey C 7-0 Fr. 1.3 1.7 11 Eugene Geter G 5-10 Fr. 7.8 1.0 21 Cedric Bozeman G 6-6 So. 8.7 5.7 15 Adam Quick G 6-2 Jr. -

Fastest 40 Minutes in Basketball, 2012-2013

University of Arkansas, Fayetteville ScholarWorks@UARK Arkansas Men’s Basketball Athletics 2013 Media Guide: Fastest 40 Minutes in Basketball, 2012-2013 University of Arkansas, Fayetteville. Athletics Media Relations Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.uark.edu/basketball-men Citation University of Arkansas, Fayetteville. Athletics Media Relations. (2013). Media Guide: Fastest 40 Minutes in Basketball, 2012-2013. Arkansas Men’s Basketball. Retrieved from https://scholarworks.uark.edu/ basketball-men/10 This Periodical is brought to you for free and open access by the Athletics at ScholarWorks@UARK. It has been accepted for inclusion in Arkansas Men’s Basketball by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UARK. For more information, please contact [email protected]. TABLE OF CONTENTS This is Arkansas Basketball 2012-13 Razorbacks Razorback Records Quick Facts ........................................3 Kikko Haydar .............................48-50 1,000-Point Scorers ................124-127 Television Roster ...............................4 Rashad Madden ..........................51-53 Scoring Average Records ............... 128 Roster ................................................5 Hunter Mickelson ......................54-56 Points Records ...............................129 Bud Walton Arena ..........................6-7 Marshawn Powell .......................57-59 30-Point Games ............................. 130 Razorback Nation ...........................8-9 Rickey Scott ................................60-62 -

2018-19 Phoenix Suns Media Guide 2018-19 Suns Schedule

2018-19 PHOENIX SUNS MEDIA GUIDE 2018-19 SUNS SCHEDULE OCTOBER 2018 JANUARY 2019 SUN MON TUE WED THU FRI SAT SUN MON TUE WED THU FRI SAT 1 SAC 2 3 NZB 4 5 POR 6 1 2 PHI 3 4 LAC 5 7:00 PM 7:00 PM 7:00 PM 7:00 PM 7:00 PM PRESEASON PRESEASON PRESEASON 7 8 GSW 9 10 POR 11 12 13 6 CHA 7 8 SAC 9 DAL 10 11 12 DEN 7:00 PM 7:00 PM 6:00 PM 7:00 PM 6:30 PM 7:00 PM PRESEASON PRESEASON 14 15 16 17 DAL 18 19 20 DEN 13 14 15 IND 16 17 TOR 18 19 CHA 7:30 PM 6:00 PM 5:00 PM 5:30 PM 3:00 PM ESPN 21 22 GSW 23 24 LAL 25 26 27 MEM 20 MIN 21 22 MIN 23 24 POR 25 DEN 26 7:30 PM 7:00 PM 5:00 PM 5:00 PM 7:00 PM 7:00 PM 7:00 PM 28 OKC 29 30 31 SAS 27 LAL 28 29 SAS 30 31 4:00 PM 7:30 PM 7:00 PM 5:00 PM 7:30 PM 6:30 PM ESPN FSAZ 3:00 PM 7:30 PM FSAZ FSAZ NOVEMBER 2018 FEBRUARY 2019 SUN MON TUE WED THU FRI SAT SUN MON TUE WED THU FRI SAT 1 2 TOR 3 1 2 ATL 7:00 PM 7:00 PM 4 MEM 5 6 BKN 7 8 BOS 9 10 NOP 3 4 HOU 5 6 UTA 7 8 GSW 9 6:00 PM 7:00 PM 7:00 PM 5:00 PM 7:00 PM 7:00 PM 7:00 PM 11 12 OKC 13 14 SAS 15 16 17 OKC 10 SAC 11 12 13 LAC 14 15 16 6:00 PM 7:00 PM 7:00 PM 4:00 PM 8:30 PM 18 19 PHI 20 21 CHI 22 23 MIL 24 17 18 19 20 21 CLE 22 23 ATL 5:00 PM 6:00 PM 6:30 PM 5:00 PM 5:00 PM 25 DET 26 27 IND 28 LAC 29 30 ORL 24 25 MIA 26 27 28 2:00 PM 7:00 PM 8:30 PM 7:00 PM 5:30 PM DECEMBER 2018 MARCH 2019 SUN MON TUE WED THU FRI SAT SUN MON TUE WED THU FRI SAT 1 1 2 NOP LAL 7:00 PM 7:00 PM 2 LAL 3 4 SAC 5 6 POR 7 MIA 8 3 4 MIL 5 6 NYK 7 8 9 POR 1:30 PM 7:00 PM 8:00 PM 7:00 PM 7:00 PM 7:00 PM 8:00 PM 9 10 LAC 11 SAS 12 13 DAL 14 15 MIN 10 GSW 11 12 13 UTA 14 15 HOU 16 NOP 7:00 -

TRADITION of EXCELLENCE Runnin’ Ute Basketball Championship Tradition a Tr a Di T Ion O F Exc E Ll Nc A

TRADITION OF EXCELLENCE Runnin’ Ute Basketball Championship Tradition E NC E LL E F EXC O ION T DI A A TR A Championships and Postseason Appearances Since 1990 Conference Champions NIT NCAA Sweet 16 1991, 1993, 1995, 1996, 1992, 2001 1991, 1996, 1997, 1998, 1997, 1998, 1999, 2000, 2005 2001, 2003, 2005 NIT Final Four 1992 NCAA Elite Eight Conference Tournament 1997, 1998 Above: All-American Andre Miller led the Utes to the Champions NCAA Tournament 1998 NCAA Final Four. Utah fell to Kentucky in the 1995, 1997, 1999, 2004 1991, 1993, 1995, 1996, NCAA Final Four championship game. 1997, 1998, 1999, 2000, 1998 2002, 2003, 2004, 2005 Below: All-American Keith Van Horn was mobbed by his teammates after hitting the game-winning shot for the second night in a row in the 1997 WAC The Utah basketball program has become one of the nation’s best since the Tournament semifinals against New Mexico. beginning of the 1990s. From its record on the court to academic success in the classroom, there are few teams in the country that can compare to the Utes’ accomplishments. • Utah has a long-standing basketball tradition, ranking sixth in NCAA history with 28 conference titles all-time. • During the decade of the ‘90s, Utah’s .767 winning percentage ranked as the eighth-best in the nation. • Utah has played in 12 NCAA Tournaments since 1990—including four consecu- tive appearances and 10 in the last 13 years. During that time, the Utes have advanced to five Sweet 16s, two Elite Eights and the national championship game in 1998. -

Cardinal Tradition Louisville Basketball

Cardinal Tradition Louisville Basketball Louisville Basketball Tradition asketball is special to Kentuckians. The sport B permeates everyday life from offices to farm- lands, from coal mines to neighborhood drug stores. It is more than just a sport played in the cold winter months. It is a source of pride filled year-round with anticipation, hope and celebration. Kentuckians love their basketball, and the tradition-rich University of Louisville program has supplied its fans with one of the nation’s finest products for decades. Legendary coach Bernard “Peck” Hickman, a Basketball Hall of Fame nominee, arrived on the UofL campus in 1944 to begin a remarkable string of 46 consecutive winning seasons. For 23 seasons, Hickman laid an impressive foundation for UofL. John Dromo, an assistant coach under Hickman for 19 years, continued the Louisville program in outstanding fashion following Hickman’s retirement. For 30 years, Denny Crum followed the same path of success that Hickman and Dromo both walked, guiding the Cardinals to even higher acclaim. Now, Coach Rick Pitino energized a re-emergence in building upon the rich UofL tradition in his 16 years, guiding the Cardinals to the 2013 NCAA championship, NCAA Final Fours in 2005 and 2012 and the NCAA Elite Eight five of the past 10 sea- sons. Among the Cardinals’ past successes include national championships in the NCAA (1980,1986, 2013), NIT (1956) and the NAIB (1948). UofL is Taquan Dean kisses the Freedom Hall floor Tremendous pride is taken in the tradition the only school in the nation to have claimed the after his final game as a Cardinal. -

1982 Football Team

The innauguration ceremony for the De La Salle Athletic Hall of Fame took place on June 10, 2007. The first-ever class of honorees included four student-athletes, one coach and one team. The class of 2007 includes the following: 1982 Football Team • Brought home De La Salle’s first-ever CAL • Ranked #2 in state at season’s end (Catholic Athletic League) and NCS titles (Class AA) • First CAL team to win a North Coast • Three players named to All-NorCal team Section title • Record 12 – 0 for the season, capped by a 49 - 0 victory over the Arroyo HS Dons in the NCS title game The team is described by Coach Ladouceur as one which “played with intensity, discipline, grit, and determination” to achieve its goal of bringing a championship to De La Salle. “They were the first Spartans, in the literal sense of the word—warriors whose mode of playing and teamwork marks them as standard-bearers for all DLS teams to come.” Their influence spread from the gridiron to all the fields of play at De La Salle: preparation, performance, excellence. Brent Barry ’90 • All-League and All-East Bay performer as a • Won the NBA Slam Dunk Contest during 2-year Varsity starter for De La Salle All-Star Week in his rookie season (1995/96) • At Oregon State University, twice chosen • One of the NBA’s best distance shooters, team MVP, junior and senior years twice hitting 7 straight 3-pt. goals • Selected to All-Pac10 team as a senior • Member of the 2007 NBA Champion San • During senior season 1994/95, averaged 21 Antonio Spurs pts. -

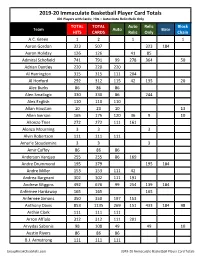

2019-20 Immaculate Basketball Checklist

2019-20 Immaculate Basketball Player Card Totals 401 Players with Cards; Hits = Auto+Auto Relic+Relic Only TOTAL TOTAL Auto Relic Block Team Auto Base HITS CARDS Relic Only Chain A.C. Green 1 2 1 1 Aaron Gordon 323 507 323 184 Aaron Holiday 126 126 41 85 Admiral Schofield 741 791 99 278 364 50 Adrian Dantley 220 220 220 Al Harrington 315 315 111 204 Al Horford 292 312 115 42 135 20 Alec Burks 86 86 86 Alen Smailagic 330 330 86 244 Alex English 110 110 110 Allan Houston 10 23 10 13 Allen Iverson 165 175 120 36 9 10 Allonzo Trier 272 272 111 161 Alonzo Mourning 3 3 3 Alvin Robertson 111 111 111 Amar'e Stoudemire 3 3 3 Amir Coffey 86 86 86 Anderson Varejao 255 255 86 169 Andre Drummond 195 379 195 184 Andre Miller 153 153 111 42 Andrea Bargnani 302 302 111 191 Andrew Wiggins 492 676 99 254 139 184 Anfernee Hardaway 165 165 165 Anfernee Simons 350 350 197 153 Anthony Davis 853 1135 269 151 433 184 98 Archie Clark 111 111 111 Arron Afflalo 312 312 111 201 Arvydas Sabonis 98 108 49 49 10 Austin Rivers 86 86 86 B.J. Armstrong 111 111 111 GroupBreakChecklists.com 2019-20 Immaculate Basketball Player Card Totals TOTAL TOTAL Auto Relic Block Team Auto Base HITS CARDS Relic Only Chain Bam Adebayo 163 347 163 184 Baron Davis 98 118 98 20 Ben Simmons 206 390 5 201 184 Bernard King 230 233 230 3 Bill Laimbeer 4 4 4 Bill Russell 104 117 104 13 Bill Walton 35 48 35 13 Blake Griffin 318 502 5 313 184 Bob McAdoo 49 59 49 10 Boban Marjanovic 264 264 111 153 Bogdan Bogdanovic 184 190 141 42 1 6 Bojan Bogdanovic 247 431 247 184 Bol Bol 719 768 99 287 333