Tobacco Policy Making in Nevada

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nevada Advisory Committee

Nevada Advisory Committee These business, faith, military, and community leaders believe that Nevada benefits when America leads in the world through investments in development and diplomacy. Hon. Richard Bryan Frank Fahrenkopf Co-Chairs U.S. Senate, (1989-2001) American Gaming Association, Former President & CEO Governor, (1983-1989) Commission on Presidential Debates, Co-Chairman Republican National Committee Chairman (1983-1989) Andy Abboud Hon. Kathleen Blakely Jack Finn Venetian Resort Hotel Casino and the Las Consulate of Japan in Las Vegas Marsy’s Law for All Vegas Sands Corporation Honorary Consul Communications Consultant Senior Vice President of Government Bob Brown Hon. Aaron Ford Relations and Community Development Opportunity Village State of Nevada Tray Abney President Attorney General The Abney Tauchen Group National Council on Disability Nevada State Senate Managing Partner Member (2013 – 2018) Andreas R. Adrian Joseph W. Brown* John Gibson International Real Estate Consultant Kolesar & Leatham Keystone Corporation Consul of the Federal Republic of Germany Of Counsel Chairman and President of the Board Honorary Consul Dr. Nancy Brune Ted Gibson* Francisco “Cisco” Aguilar Kenny Guinn Center for Policy Priorities Nevada State Boxing Commission Crest Insurance Group Executive Director Inspector General Counsel and President – Nevada A.G. Burnett Rew R. Goodenow Debra D. Alexandre McDonald Carano Parsons Behle & Latimer Nevada State Development Corporation Partner Lawyer President Emeritus Nevada Gaming Control Board Rabbi Felipe Goodman Former Chairman Gayle M. Anderson Temple Beth Sholom City of Las Vegas & Las Vegas Global Economic Dr. Joe Carleone Head Rabbi Alliance AMPAC Fine Chemicals John Groom* International Chief of Protocol Chairman Paragon Gaming June Beland Dr. Susan Clark Chief Operation Officer Women’s Chamber of Commerce of Nevada Nevada Venture Accelerator Kelly Matteo Grose Founder, President & CEO Founder & President World Affairs Council of Las Vegas Dr. -

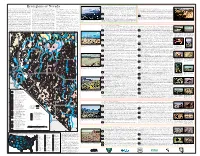

Ecoregions of Nevada Ecoregion 5 Is a Mountainous, Deeply Dissected, and Westerly Tilting Fault Block

5 . S i e r r a N e v a d a Ecoregions of Nevada Ecoregion 5 is a mountainous, deeply dissected, and westerly tilting fault block. It is largely composed of granitic rocks that are lithologically distinct from the sedimentary rocks of the Klamath Mountains (78) and the volcanic rocks of the Cascades (4). A Ecoregions denote areas of general similarity in ecosystems and in the type, quality, Vegas, Reno, and Carson City areas. Most of the state is internally drained and lies Literature Cited: high fault scarp divides the Sierra Nevada (5) from the Northern Basin and Range (80) and Central Basin and Range (13) to the 2 2 . A r i z o n a / N e w M e x i c o P l a t e a u east. Near this eastern fault scarp, the Sierra Nevada (5) reaches its highest elevations. Here, moraines, cirques, and small lakes and quantity of environmental resources. They are designed to serve as a spatial within the Great Basin; rivers in the southeast are part of the Colorado River system Bailey, R.G., Avers, P.E., King, T., and McNab, W.H., eds., 1994, Ecoregions and subregions of the Ecoregion 22 is a high dissected plateau underlain by horizontal beds of limestone, sandstone, and shale, cut by canyons, and United States (map): Washington, D.C., USFS, scale 1:7,500,000. are especially common and are products of Pleistocene alpine glaciation. Large areas are above timberline, including Mt. Whitney framework for the research, assessment, management, and monitoring of ecosystems and those in the northeast drain to the Snake River. -

Political History of Nevada: Chapter 1

Political History of Nevada Chapter 1 Politics in Nevada, Circa 2016 37 CHAPTER 1: POLITICS IN NEVADA, CIRCA 2016 Nevada: A Brief Historiography By EMERSON MARCUS in Nevada Politics State Historian, Nevada National Guard Th e Political History of Nevada is the quintessential reference book of Nevada elections and past public servants of this State. Journalists, authors, politicians, and historians have used this offi cial reference for a variety of questions. In 1910, the Nevada Secretary of State’s Offi ce fi rst compiled the data. Th e Offi ce updated the data 30 years later in 1940 “to meet a very defi nite and increasing interest in the political history of Nevada,” and has periodically updated it since. Th is is the fi rst edition following the Silver State’s sesquicentennial, and the State’s yearlong celebration of 150 years of Statehood in 2014. But this brief article will look to examine something other than political data. It’s more about the body of historical work concerning the subject of Nevada’s political history—a brief historiography. A short list of its contributors includes Dan De Quille and Mark Twain; Sam Davis and James Scrugham; Jeanne Wier and Anne Martin; Richard Lillard and Gilman Ostrander; Mary Ellen Glass and Effi e Mona Mack; Russell Elliott and James Hulse; William Rowley and Michael Green. Th eir works standout as essential secondary sources of Nevada history. For instance, Twain’s Roughing It (1872), De Quille’s Big Bonanza (1876) and Eliot Lord’s Comstock Mining & Mines (1883) off er an in-depth and anecdote-rich— whether fact or fi ction—glance into early Nevada and its mining camp way of life. -

Nye County Agenda Information Form

NYE COUNTY AGENDA INFORMATION FORM Action U Presentation U Presentation & Action Department: Town of Pahrump — County Manager Agenda Date: Category: Times Agenda Item — 10:00 a.m. June 24, 2020 Phone: Continued from meeting of: Contact: Tim Sutton June 162020 Puone: Return to: Location: Pabrunip A clion reqti estecl: (Include whai with whom, when, where, why, how much (5) and terms) Presentation, discussion and deliberation regarding the renewal proposal for the Town of Pahrump from the Nevada Public Agency Insurance Pool (POOL) for Fiscal Year 2020-2021 with a maintenance deductible in the amount ofS2.000.00 and a premium in the amount ofSl33,053.30. Complete description of requested action: (Include, if applicable, background, impact, long-tenn commitment, csisling county policy, future goals, obtained by competitive hid, accountability measures) The maintenance deductible for Fiscal Year 2019-2020 is $2,000.00 and the premium was $172,320.21. provide 20 Any information provided after the agenda is published or tluring the meeting of the Commissioners will require on to for County Manager. copies one for each Commissioner, one for the Clerk, one for the District Attorney, one for the Public and two the Contracts or documents requiring signature must be submitted with three original copies. Expenditure Impact by FY(s): (Provide detail on Financial Foon) No financial impact Routing & Approval (Sign & Date) Dale Dae 1. Dept 6 tlnte Dale D HR 2. ° D. 3. 8. Legal ; Date Dale I 4 9. Finance Dale Cottnty Manager aee on Agenda Dale 5 io. ITEM# — ITEM 9 PAGE 001 NEVADA PUBLIC AGENCY INSURANCE POOL MEMBER COVERAGE SUMMARY Prepared For: Pahrump, Town of Prepared By: LP Insurance Services, Inc. -

Directory of State and Local Government

DIRECTORY OF STATE AND LOCAL GOVERNMENT Prepared by RESEARCH DIVISION LEGISLATIVE COUNSEL BUREAU 2020 Table of Contents TABLE OF CONTENTS Please refer to the Alphabetical Index to the Directory of State and Local Government for a complete list of agencies. NEVADA STATE GOVERNMENT ORGANIZATIONAL CHART ............................................. D-9 CONGRESSIONAL DELEGATION ............................................................................................. D-13 DIRECTORY OF STATE GOVERNMENT CONSTITUTIONAL OFFICERS: Attorney General ........................................................................................................................ D-15 State Controller ........................................................................................................................... D-19 Governor ..................................................................................................................................... D-20 Lieutenant Governor ................................................................................................................... D-27 Secretary of State ........................................................................................................................ D-28 State Treasurer ............................................................................................................................ D-30 EXECUTIVE BOARDS ................................................................................................................. D-31 NEVADA SYSTEM OF HIGHER EDUCATION -

News Release

News Release Texans for Public Justice * 609 W. 18th Street, Suite E, * Austin, TX 78701 * tpj.org For Immediate Release: Contact: Craig McDonald, October 18, 2011 Andrew Wheat PH: (512) 472-9770 The House May Be Betting on Perry at Tonight’s Venetian Casino Debate Texas Governor and Las Vegas Sands Croupier Sheldon Adelson Have Wealth of Ties Austin—Tonight’s Republican presidential debate at Las Vegas’ Venetian Resort Hotel Casino takes Texas Governor Rick Perry back to the same sprawling complex where he attended his son’s 2009 bachelor party. Las Vegas Sands Corp. owns the Venetian, which is hosting the debate, and it owns the adjoining Palazzo Resort-Hotel- Casino, where Perry bedded down the night of his son’s party. The head of Las Vegas Sands, Sheldon Adelson, has been a Perry supporter since 2007. Perry’s campaign reported that he flew to Vegas on October 24, 2009 to meet Brian Sandoval, who was then running a successful GOP campaign to be governor of Nevada. Days later the campaign acknowledged to the Dallas Morning News that on that same Vegas trip Perry also attended a bachelor party that the male friends of his son, Griffin, held to celebrate the younger Perry’s upcoming wedding.1 Perry previously reported that casino owner Adelson contributed a $1,856 in-kind “event expense” to the Perry campaign on December 7, 2007. Perry’s campaign reported that one of its fundraisers, Krystie Alvarado, flew to Vegas a day earlier for a fundraiser. The campaign reported that Flatonia, Texas sausage magnate Danny Janecka then flew Governor Perry to Vegas on December 9, 2007 for a fundraiser. -

Drivingwalking06.25.Pdf

Driving Tours Lincoln County Lincoln County Driving Tours 1 Lower and Upper Pahranagat Lakes Travel approximately 4 miles south of Alamo and turn west at the identification signs. South of the town of Alamo, the run-off from White 50 River flows into an idyllic, pastoral, 50 acre lake. 6 This lake is called Upper Pahranagat Lake and is just over 2 miles long and a half mile wide. It is encircled with beautiful shade trees, brush and grasses. The surrounding land is designated as a National Wildlife Preserve and the area has become a permanent home for birds such as duck, geese, quail, blue herons, and many varieties of smaller birds. Migrating birds include swans and pelicans 19 that pass through in winter and spring. The overflow from the Upper Pahranagat Lake is carried downstream about 4 miles to Lower Pahranagat Lake. This lake is slightly less than a mile and a half long and about a half mile wide. Fishing in early spring and summer is excellent. During the summer months, water is used for irrigation and reduces the 18 level of both lakes. 17 16 Ursine 2 Pioche 15 13 322 Alamo–A Historic Pahranagat Valley Town 318 12 14 Continue north about 4 miles from Upper Pahranagat 11 Lake or south 9 miles from Ash Springs on U.S. 93 to 10 9 319 Panaca the historic town of Alamo. See the Alamo Walking Tour in this brochure for individual attractions. Caliente Rachel 21 93 5 Alamo, the principal town of Hiko 20 6 Pahranagat Valley, was formed around 7 8 1900 by Fred Allen, Mike Botts, Bert 375 Ash Springs 3 4 317 Riggs and William T. -

An Interview with LINA SHARP

An Interview with LINA SHARP An Oral History conducted and edited by Robert D. McCracken Nye County Board of Commissioners Nye County, Nevada Tonopah 1992 COPYRIGHT 1992 Nye County Town History Project Nye County Commissioners Tonopah, Nevada 89049 Lina Pinjuv Sharp, Blue Eagle Ranch, Railroad Valley, NV 1941 Jim Sharp, Blue Eagle Ranch, Railroad Valley, NV, 1941 CONTENTS Preface Acknowledgments Introduction CHAPTER ONE Lina discusses her parents, Ivan and Anna Lalich Pinjuv, who both came to the U.S. from Yugoslavia; Lina's childhood and youth in Los Angeles and Las Vegas, including memories of the Mikulich family and of a hospital stay where Lina experienced Las Vegas's first air conditioning; Lina's college years in Reno and her first teaching assignment — at the Blue Eagle Ranch; a discussion of the Bordoli family and the Bordoli Ranch; Lina recalls Mary McCann Sharp; the children Lina taught at Blue Eagle. CHAPTER TWO Lina's first year teaching at Blue Eagle; the name Blue Eagle; Lina marries Jim Sharp and becomes a permanent resident of Railroad Valley; the Sharp family's progenitor, Henry Sharp, and his son George (Lina's father-in-law); the route of the Midland Trail, which passed through the Blue Eagle Ranch; some history of the communities near Blue Eagle — Nyala, Troy, Grant, and Irwin canyons; George Sharp purchases Blue Eagle and meets his future bride, Mary- McCann; McCann Station between Hot Creek and Tybo. CHAPTER THREE George and Mary McCann Sharp spend some years in Belmont, then return to Blue Eagle; the children and grandchildren of George and Mary; the Sharps's Blue Eagle Ranch and its grazing land; Lina recalls the Blue Eagle Ranch as it was in 1940; federal government interference at Blue Eagle; drilling for potash near Blue Eagle and finding water; the Locke Ranch; Emery Garrett of Nyala and Currant Creek; some history on Nyala. -

Guide to the Elbert Edwards Photograph Collection

Guide to the Elbert Edwards Photograph Collection This finding aid was created by Lindsay Oden. This copy was published on August 04, 2021. Persistent URL for this finding aid: http://n2t.net/ark:/62930/f1c03n © 2021 The Regents of the University of Nevada. All rights reserved. University of Nevada, Las Vegas. University Libraries. Special Collections and Archives. Box 457010 4505 S. Maryland Parkway Las Vegas, Nevada 89154-7010 [email protected] Guide to the Elbert Edwards Photograph Collection Table of Contents Summary Information ..................................................................................................................................... 3 Biographical Note ............................................................................................................................................ 3 Scope and Contents Note ................................................................................................................................ 4 Arrangement .................................................................................................................................................... 4 Administrative Information ............................................................................................................................. 5 Related Materials ............................................................................................................................................. 5 Names and Subjects ....................................................................................................................................... -

IIS Windows Server

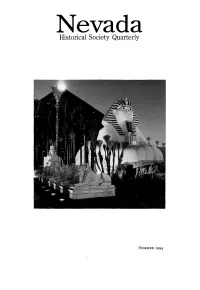

Nevada Historical Society Quarterly SUMMER 1994 NEV ADA HISTORICAL SOCIETY QUARTERLY EDITORIAL BOARD Eugene Moehring, Chairman, University of Nevada, Las Vegas Marie Boutte, University of Nevada, Reno Robert Davenport, University of Nevada, Las Vegas Doris Dwyer, Western Nevada Community College Jerome E. Edwards, University of Nevada, Reno Candace C. Kant, Community College of Southern Nevada Guy Louis Rocha, Nevada State Library and Archives Willard H. Rollings, University of Nevada, Las Vegas Hal K. Rothman, University of Nevada, Las Vegas The Nevada Historical Society Quarterly solicits contributions of scholarly or popular interest dealing with the following subjects: the general (e.g., the political, social, economic, constitutional) or the natural history of Nevada and the Great Basin; the literature, languages, anthropology, and archaeology of these areas; reprints of historic documents; reviews and essays concerning the historical literature of Nevada, the Great Basin, and the West. Prospective authors should send their work to The Editor, Nevada Historical Society Quarterly, 1650 N. Virginia St., Reno, Nevada 89503. Papers should be typed double-spaced and sent in duplicate. All manuscripts, whether articles, edited documents, or essays, should conform to the most recent edition of the University of Chicago Press Manual of Style. Footnotes should be typed double-spaced on separate pages and numbered consecutively. Correspondence concerning articles and essays is welcomed, and should be addressed to The Editor. © Copyright Nevada Historical Society, 1994. The Nevada Historical Society Quarterly (ISSN 0047-9462) is published quarterly by the Nevada Historical Society. The Quarterly is sent to all members of the Society. Membership dues are: Student, $15; Senior Citizen without Quarterly, $15; Regular, $25; Family, $35; Sustaining, $50; Contributing, $100; Departmental Fellow, $250; Patron, $500; Benefactor, $1,000. -

Billions: the Politics of Influence in the United States, China and Israel

Volume 6 | Issue 7 | Article ID 2829 | Jul 02, 2008 The Asia-Pacific Journal | Japan Focus Billions: The Politics of Influence in the United States, China and Israel Connie Bruck, Peter Dale Scott Billions: The Politics of Influence in the Thatcher, who in turn passed legislation United States, China and Israel enabling Murdoch to crush the powerful trades unions of Fleet Street. In America, Murdoch’s Peter Dale Scott and Connie Bruck Fox News, New York Post, and Weekly Standard underwrote the meteoric rise of the neocons in the Project for the New American Century (PNAC), whose Chairman was William Introduction Kristol, editor of The Weekly Standard. [2] Peter Dale Scott Connie Bruck’s account of billionaire Sheldon Adelson using his millions to refashion the politics of Israel strikes several familiar notes. Around the world states are in standoffs against their richest citizens. In Thailand Thaksin Shinawatra has challenged the traditional monarchist establishment of the country. The Russian oligarchs dominated Russian politics for a decade in the Yeltsin era. In Mexico a similar role has been played by oligarchs such as Carlos Hank González (d. 2001), and Carlos Slim Helù, today the second Rupert Murdoch with his third wife, Wendy richest man in the world. Deng in 2001 In many cases, billionaires have used their From an American perspective, it is hard to control of media to solidify their influence in think of anyone surpassing the influence of politics. This was the strategy in Canada of Murdoch. But according to the 2008 Forbes Conrad Black, for a time (before his conviction 400, Murdoch, with a net worth of $8.3 billion, on fraud charges) "the third biggest newspaper is only the 109th-richest person in the world. -

Pahranagat Wilderness

WHAT IS A NATIONAL WILDLIFE REFUGE? Pahranagat NATIONAL WILDLIFE REFUGE Simply put, national wildlife refuges are places where wildlife comes first. With over 550 refuges throughout the United States, the National Wildlife Refuge System is the only network of federal © U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service lands dedicated specifically to wildlife conservation. The Desert National Wildlife Refuge Complex Southern Nevada has four national wildlife refuges all within an hour and a half drive from Las Vegas: Desert, Pahranagat, Moapa Valley, and Ash Meadows. Many wildlife refuges, like Pahranagat NWR, were established to protect and enhance the resting and feeding grounds of migratory birds, creating a chain of stepping stones along major migration routes. Others, like Desert, Moapa Valley, and Ash Meadows, were established to conserve the natural homes of our rarest wild species, including desert bighorn sheep, unique wildflowers, and rare desert fish. © Southern Nevada Agency Partnership Wilderness in Your Backyard Get away from the rush and noise of the city. The national wildlife refuges in southern Nevada PAHRANAGAT National Wildlife Refuge allow you to experience a real sense of wilderness, marvel at the beauty of the Mojave Desert, watch rare wildlife in their native habitat, and know it will be here for generations to come. © U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service Few landscapes are as contrasting as Pahranagat Visit this unique oasis during the spring and fall © U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service Valley’s lush wetlands and the surrounding Mojave migrations for the best chance to see festive displays America’s Great Outdoors Desert. Life-giving waters from Crystal and Ash Springs of colorful song birds NEVADA 2012 flow through the valley, nourishing the Pahranagat and a diversity National Wildlife Refuge and offering ideal wetland of ducks and and riparian habitats for thousands of migratory birds, other waterfowl numerous birds of prey, deer, and rare fish.