University of Florida Libraries

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Event Winners

Meet History -- NCAA Division I Outdoor Championships Event Winners as of 6/17/2017 4:40:39 PM Men's 100m/100yd Dash 100 Meters 100 Meters 1992 Olapade ADENIKEN SR 22y 292d 10.09 (2.0) +0.09 2017 Christian COLEMAN JR 21y 95.7653 10.04 (-2.1) +0.08 UTEP {3} Austin, Texas Tennessee {6} Eugene, Ore. 1991 Frank FREDERICKS SR 23y 243d 10.03w (5.3) +0.00 2016 Jarrion LAWSON SR 22y 36.7652 10.22 (-2.3) +0.01 BYU Eugene, Ore. Arkansas Eugene, Ore. 1990 Leroy BURRELL SR 23y 102d 9.94w (2.2) +0.25 2015 Andre DE GRASSE JR 20y 215d 9.75w (2.7) +0.13 Houston {4} Durham, N.C. Southern California {8} Eugene, Ore. 1989 Raymond STEWART** SR 24y 78d 9.97w (2.4) +0.12 2014 Trayvon BROMELL FR 18y 339d 9.97 (1.8) +0.05 TCU {2} Provo, Utah Baylor WJR, AJR Eugene, Ore. 1988 Joe DELOACH JR 20y 366d 10.03 (0.4) +0.07 2013 Charles SILMON SR 21y 339d 9.89w (3.2) +0.02 Houston {3} Eugene, Ore. TCU {3} Eugene, Ore. 1987 Raymond STEWART SO 22y 80d 10.14 (0.8) +0.07 2012 Andrew RILEY SR 23y 276d 10.28 (-2.3) +0.00 TCU Baton Rouge, La. Illinois {5} Des Moines, Iowa 1986 Lee MCRAE SO 20y 136d 10.11 (1.4) +0.03 2011 Ngoni MAKUSHA SR 24y 92d 9.89 (1.3) +0.08 Pittsburgh Indianapolis, Ind. Florida State {3} Des Moines, Iowa 1985 Terry SCOTT JR 20y 344d 10.02w (2.9) +0.02 2010 Jeff DEMPS SO 20y 155d 9.96w (2.5) +0.13 Tennessee {3} Austin, Texas Florida {2} Eugene, Ore. -

Etn1956 Vol02 21

TRACK NEwSL TER Vol. 2, No. 21, June 19, 1956 P.O. Box 296, Los Altos, Calif. By Bert & Cordner Nelson, Track & F'ield News $6 per year (24 issues) NEWS NCAA, Berkeley, June 15-16: 100- Morrow 10.4 (a gainst wind), Sime 10.55,. \.___,, Agostini . 10.55, Kin g 10, 6 , Kave10.6, Blair 10.7; 200-Morrow 20.6 turn; e quals be st ev er, Blair 21. 0 , Whi l de n 21. 2, Ago st i ri"l21 . 2 , Brabham r 2 1. 4., Se grest 21 .5. ( Sime pulled u p lame); 1-1-00-Ma shbu rn 46.4, Ha i nes 46.4, Jenkins 46 . 6 , Ellis46.7, Wash i n gton 47:T, Pe r kins 47._,2; 800 - Sowell 1:4 6 .7, American record, Sta nl ey 1:4 9 .2, Brew 1:50.5, Johnson 1: 50 . 5 , Had l ey 1: 5 1.1, Jan zen 1:52. 9 (Kirkby 3rd 1: 50 . 2 but disquali fi ed ); 1500 - Delany 3 :1.~7.3 (54 .1 last l.1_L~0), Bai l ey 3:47. 5 , Wing 3:Li.9 .7 ,. Sean1an 'JT[f9'.7, Whee l er J :50. 4 , :Murphey J:52.0; J OOOSC-Kennedy 9 :1 6 ,5., Matza 9 :17.2, Kielstru p 9 : 34 -4 , Hubbard 9 :42 .7, Peterson 9 :46 .1, · Fergus on 10:01.1; 5000-Delli ng er 14: 48 .5, Beatty 14 : 51 ,1, Jones 14: 52 .2, Truex l LJ.: 53 .5, Wallin gford ll+:53.7, Shim 15 :0L~.14-; 10,000 (F'riday ; J ones 31 :15.3, House 31:4.6 , Sbarra 32: 0l , Frame 32 : 24 .7, McNeal · 32:42.6, McClenathen 33:13,0; ll OI:I-Calhoun 13.7, J ohnson 13 . -

Yakima Valley Invitational “99”

Yakima Valley AAU Three Rivers Winter League 2007 Presented by the Yakima Valley Sports Authority 6th Grade Girls FINAL RESULTS Division Name: Glenn Davis, Athletics 1958 Division Name: Bobby Morrow, Athletics 1957 Place No. Team Name Win Loss Place No. Team Name Win Loss 1st 1 Kimmel Stars – Yakima 3 1 1st 7 East Valley She Devils 4 0 2nd 2 Wapato Stars 3 1 2nd 9 Ellensburg Tigers (+6, -2 = +4) 2 2 3rd 3 Tri City Panthers 2 2 3rd 6 Sunnyside (+7, -6 = +1) 2 2 4th 4 Grandview Valley Girls 2 2 4th 10 Wapato Lady Cubs (+2, -7 = -5) 2 2 5th 5 Lightning 0 4 5th 8 Prosser Super Hoopers 0 4 Division Name: Patricia McCormick, Diving 1956 Division Name: Harrison Dillard, Athletics 1955 Place No. Team Name Win Loss Place No. Team Name Win Loss 1st 11 Toppenish Wildcats 4 0 1st 18 Mabton Lady Viks 4 0 2nd 13 East Valley Dribblers Too 3 1 2nd 19 Prosser – Childers (-1, +13 = +12) 2 2 3rd 14 Granger Red Storm 2 2 3rd 16 Benton City (+1, -2 = -1) 2 2 4th 15 Upper Valley Stars 1 3 4th 17 Sunnyside Christian (+2, -13 = -11) 2 2 5th 12 Zillah Cyclones 0 4 5th 20 Goldendale – Lawrence 0 4 Division Name: Malvin Whitfield, Athletics 1954 Division Name: Sammy Lee, Diving 1953 Place No. Team Name Win Loss Place No. Team Name Win Loss 1st 25 West Richland Wildcats (+15, -5 = +10) 4 1 1st 29 Club Yakima 5 0 2nd 23 Pasco Heat (+15, -15 = 0) 4 1 2nd 30 Cle Elum AC/DC Electric Sparks 4 1 3rd 21 Burbank Ligers (-15, +5 = -10) 4 1 3rd 27 Selah Spice 3 2 4th 22 Kennewick Rebels 2 3 4th 32 Yakima Tigers (+15, -3 = +12) 1 4 5th 24 Prosser – Morado 1 4 5th 31 Yakima Renegades (+3, -1 = +2) 1 4 6th 26 Mattawa 0 5 6th 28 Kittitas Pillar Hoops (-15, +1 = -14) 1 4 Division Name: Horace Ashenfelter III, Athletics 1952 Place No. -

NEWSLETTER Supplementingtrack & FIELD NEWS Twice Monthly

TRACKNEWSLETTER SupplementingTRACK & FIELD NEWS twice monthly. Vol. 10, No. 1 August 14, 1963 Page 1 Jordan Shuffles Team vs. Germany British See 16'10 1-4" by Pennel Hannover, Germany, July 31- ~Aug. 1- -Coach Payton Jordan London, August 3 & 5--John Pennel personally raised the shuffled his personnel around for the dual meet with West Germany, world pole vault record for the fifth time this season to 16'10¼" (he and came up with a team that carried the same two athletes that com has tied it once), as he and his U.S. teammates scored 120 points peted against the Russians in only six of the 21 events--high hurdles, to beat Great Britain by 29 points . The British athl_etes held the walk, high jump, broad jump, pole vault, and javelin throw. His U.S. Americans to 13 firsts and seven 1-2 sweeps. team proceeded to roll up 18 first places, nine 1-2 sweeps, and a The most significant U.S. defeat came in the 440 relay, as 141 to 82 triumph. the Jones boys and Peter Radford combined to run 40 . 0, which equal The closest inter-team race was in the steeplechase, where ed the world record for two turns. Again slowed by poor baton ex both Pat Traynor and Ludwig Mueller were docked in 8: 44. 4 changes, Bob Hayes gained up to five yards in the final leg but the although the U.S. athlete was given the victory. It was Traynor's U.S. still lost by a tenth. Although the American team had hoped second fastest time of the season, topped only by his mark against for a world record, the British victory was not totally unexpected. -

Mrnmmmmmmjmk*' Cheyney G.F.Pts

THE SUNDAY STAR, Washington, D. C. ** SUNDAY, JANUARY 10, I»A4 C-3 Field for Star Games Bolstered by Flood of New York Talent ? Lack of Any Conflict TV Board Renamed, Golden Gloves Entries Byrd Guest Speaker Jan. 23 Makes D. C. gfl w Emphasizing NCAA's Indicate Battle tor At Home Plate Event Dr. H C. (Curley) Byrd, presi- Track World Capital Stand-Pat Policy Heavyweight Honors & beat dent emeritus of Maryland Uni- « versity, guest By BURTON HAWKINS will be speaker at By Rod Thomas By Ik Auociatad Pratt Early entry lists indicate the the third annual banquet of the For 35 years, as boy man, CINCINNATI. Jan. 9.—The accent will be heavyweights and on For the first time since he be- and Dick Kokos of the Orioles, Dorsey J. Griffith, the old George- Council of the National Collegi- Home Plate Club at 7:30 pm. and light-heavyweights in the came affiliated with the Sena- . Any significance in the fact town sprinter, steeped ate Athletic Association reap- | Saturday at the National Press has been boxing years ago. that five of the eight are in track and field. Few men pointed its television committee Golden Gloves tourna- tors more than 40 have Clark Griffith won’t stay at the pitchers? Club. so today with only one change. ment opening January 19 at been closely same hotel Baltimore officials apparently Also expected to attend are identified with Wilbur V. Hubbard of San Turner’s Arena. Jose State College replaces M. I. no longer are proud of their pre- Senator Johnson of Colorado, Seldom before in the history ! . -

Leading Men at National Collegiate Championships

LEADING MEN AT NATIONAL COLLEGIATE CHAMPIONSHIPS 2020 Stillwater, Nov 21, 10k 2019 Terre Haute, Nov 23, 10k 2018 Madison, Nov 17, 10k 2017 Louisville, Nov 18, 10k 2016 Terre Haute, Nov 19, 10k 1 Justyn Knight (Syracuse) CAN Patrick Tiernan (Villanova) AUS 1 2 Matthew Baxter (Nn Ariz) NZL Justyn Knight (Syracuse) CAN 2 3 Tyler Day (Nn Arizona) USA Edward Cheserek (Oregon) KEN 3 4 Gilbert Kigen (Alabama) KEN Futsum Zienasellassie (NA) USA 4 5 Grant Fisher (Stanford) USA Grant Fisher (Stanford) USA 5 6 Dillon Maggard (Utah St) USA MJ Erb (Ole Miss) USA 6 7 Vincent Kiprop (Alabama) KEN Morgan McDonald (Wisc) AUS 7 8 Peter Lomong (Nn Ariz) SSD Edwin Kibichiy (Louisville) KEN 8 9 Lawrence Kipkoech (Camp) KEN Nicolas Montanez (BYU) USA 9 10 Jonathan Green (Gtown) USA Matthew Baxter (Nn Ariz) NZL 10 11 E Roudolff-Levisse (Port) FRA Scott Carpenter (Gtown) USA 11 12 Sean Tobin (Ole Miss) IRL Dillon Maggard (Utah St) USA 12 13 Jack Bruce (Arkansas) AUS Luke Traynor (Tulsa) SCO 13 14 Jeff Thies (Portland) USA Ferdinand Edman (UCLA) NOR 14 15 Andrew Jordan (Iowa St) USA Alex George (Arkansas) ENG 15 2015 Louisville, Nov 21, 10k 2014 Terre Haute, Nov 22, 10k 2013 Terre Haute, Nov 23, 9.9k 2012 Louisville, Nov 17, 10k 2011 Terre Haute, Nov 21, 10k 1 Edward Cheserek (Oregon) KEN Edward Cheserek (Oregon) KEN Edward Cheserek (Oregon) KEN Kennedy Kithuka (Tx Tech) KEN Lawi Lalang (Arizona) KEN 1 2 Patrick Tiernan (Villanova) AUS Eric Jenkins (Oregon) USA Kennedy Kithuka (Tx Tech) KEN Stephen Sambu (Arizona) KEN Chris Derrick (Stanford) USA 2 3 Pierce Murphy -

USATF Cross Country Championships Media Handbook

TABLE OF CONTENTS NATIONAL CHAMPIONS LIST..................................................................................................................... 2 NCAA DIVISION I CHAMPIONS LIST .......................................................................................................... 7 U.S. INTERNATIONAL CROSS COUNTRY TRIALS ........................................................................................ 9 HISTORY OF INTERNATIONAL CHAMPIONSHIPS ........................................................................................ 20 APPENDIX A – 2009 USATF CROSS COUNTRY CHAMPIONSHIPS RESULTS ............................................... 62 APPENDIX B –2009 USATF CLUB NATIONAL CHAMPIONSHIPS RESULTS .................................................. 70 USATF MISSION STATEMENT The mission of USATF is to foster sustained competitive excellence, interest, and participation in the sports of track & field, long distance running, and race walking CREDITS The 30th annual U.S. Cross Country Handbook is an official publication of USA Track & Field. ©2011 USA Track & Field, 132 E. Washington St., Suite 800, Indianapolis, IN 46204 317-261-0500; www.usatf.org 2011 U.S. Cross Country Handbook • 1 HISTORY OF THE NATIONAL CHAMPIONSHIPS USA Track & Field MEN: Year Champion Team Champion-score 1954 Gordon McKenzie New York AC-45 1890 William Day Prospect Harriers-41 1955 Horace Ashenfelter New York AC-28 1891 M. Kennedy Prospect Harriers-21 1956 Horace Ashenfelter New York AC-46 1892 Edward Carter Suburban Harriers-41 1957 John Macy New York AC-45 1893-96 Not Contested 1958 John Macy New York AC-28 1897 George Orton Knickerbocker AC-31 1959 Al Lawrence Houston TFC-30 1898 George Orton Knickerbocker AC-42 1960 Al Lawrence Houston TFC-33 1899-1900 Not Contested 1961 Bruce Kidd Houston TFC-35 1901 Jerry Pierce Pastime AC-20 1962 Pete McArdle Los Angeles TC-40 1902 Not Contested 1963 Bruce Kidd Los Angeles TC-47 1903 John Joyce New York AC-21 1964 Dave Ellis Los Angeles TC-29 1904 Not Contested 1965 Ron Larrieu Toronto Olympic Club-40 1905 W.J. -

Norcal Running Review Is Published on a Monthly Basis by the West Valley Track Club

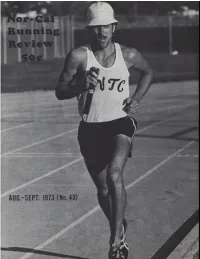

the athletic department RUNNING UNLIMITED JOHN KAVENY ON THE COVER West Valley Track Club's Jim Dare dur ing the final mile (4:35.8), his 30th, in the Runner's World sponsored 24-Hr Relay at San Jose State. Dare's aver age for his 30 miles was 4:47.2, and he led his teammates to a new U.S. Club Record of 284 miles, 224 yards, break ing the old mark, set in 1972 by Tulsa Running Club, by sane nine miles. Full results on pages 17-18. /Wayne Glusker/ STAFF EDITOR: Jack Leydig; PRINTER: Frank Cunningham; PHOTOGRA PHERS: John Marconi, Dave Stock, Wayne Glusker; NOR-CAL PORTRAIT CONTENTS : Jon Hendershott; COACH'S CORNER: John Marconi; WEST VALLEY PORTRAIT: Harold DeMoss; NCRR POINT RACE: Art Dudley; Readers' Poll 3 West Valley Portrait 10 WOMEN: Roxy Andersen, Harmon Brown, Jim Hume, Vince Reel, Dawn This & That 4 Special Articles 10 Bressie; SENIORS: John Hill, Emmett Smith, George Ker, Todd Fer NCRR LDR Point Ratings 5 Scheduling Section 12 guson, David Pain; RACE WALKING: Steve Lund; COLLEGIATE: Jon Club News 6 Race Walking News 14 Hendershott, John Sheehan, Fred Baer; HIGH SCHOOL: Roy Kissin, Classified Ads 8 Track & Field Results 14 Dave Stock, Mike Ruffatto; AAU RESULTS: Jack Leydig, John Bren- Letters to the Editor 8 Road Racing Results 16 nand, Bill Cockerham, Jon Hendershott. --- We always have room for Coach's Comer 9 Late News 23 more help on our staff, especially in the high school and colle NorCal Portrait 9 giate areas, now that cross country season has begun. -

An Annotated Bibliography of Track and Field Books Published in the United States Between 1960-1974

OCUMENT RESUME EDtf47V71 SP 011.838. AUTHOR MorrisonRay-Leon TITLE An:Ahnot ted Biblidgraphy of Track and Field Books Published in the. United States Between 1960-1974. I PUB DATE Jun 75 . NOTE 115p.; Master's Thsis, San Jose State University EDRS-PE/CE MF-$0.83.He-$6.01 PI s Postage. DESSRIPTORS , *Annotated Bibliograpies; *Athle'teS;'*Athletics; Bibliographic Citatioh; *Lifetime Sports; Physical Education; Running; *Trckad d Field , ABSTRACT This book is a cbmprebensi a anotated bibliography of every,:track and field book published in t e b te.a States from 1960 to 1974. Running events, field event, generareading, biographies, records and statistics are included. Bach entry is fully annotated. Major track and field publishers are-listed as as track anOofield periodicals. (JD) ) . f , **********************************************************************. 4 t . 1 * * . Docusents acquired by ERIC include manyinformal unpublished * materials not available from other sources. ERIC sakes every effort* * to obtain the best copy available. Nevertheless, itemsof marginal * * reproducibility are often encountered and this affects the quality * * of the microfiche and hardcopy reproductions ERIC wakes 4 ailable .* * via the ERIC Document 'Reproduction Service (EDES).-EDRS s not' * * responsible for the quality of the origihal document. productions* supplied'by HORS are the best that can be made from th original. *_ 2*****41****M4***44**************4144#*********#44********************** 4 I AN ANNOTATED BIBLIORAPHY* 0-1 TRACN AND FIELD BOORS lk c\J 4.13LISHED IN, uNimp STATES BETWEEN. 1960-1974 4 r-4 C) r NA:J. O 4 A Research Paper Presented to . ., . the Faculty of tha Department of Librd'rianship . San Jose State University 04 In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Deig;ee. -

Derby Today Place in Star West 'Over His Head' in Will Ose, Or Tourney Meeting Caps Start Trio Your Host Big Choice; by GRANTLAND RICE Earned by G

^ netting f&to Fast Track pnrfs* for Santa Anita Washington, D. C., Saturday, February 18, 1950—A—12 Likely Derby Today Place in Star West 'Over His Head' in Will ose, or Tourney Meeting Caps Start Trio Your Host Big Choice; By GRANTLAND RICE Earned by G. W. High, Williams, TKO Winner in 8th Of Back-Court Aces More Than 50,000 The Greatest of Them All LOS ANGELES, Feb. 18.—Who is the greatest woman tennis Winner Over W.-L. Against Olympians Due to See Race star of all time? We transfer you from the East, the South and George Washington High of Bill Fuchs By ths Associated Pres* the Midwest to Southern California where George Byrnes brings By Alexandria, winner of The Star's Bob Feerick, player-coach of the ARCADIA, Calif., Feb. 18.— in Perry Jones and Maurice McLoughlin to give you the answer. Metropolitan high school basket- Washington Caps, has something William Getz’s Your Host was a Mr. takes over: Byrnes new to throw at the favorite as ball tournament last year, Is the Indianapolis prohibitive today a “Dear Grant: Everybody who knows him has a tremendous Olympians tonight when the two field of one dozen awaited the first team to receive and accept a respect for Perry T. Jones’s opinion on tennis teams meet in the final game of start of the S100.000 Santa Anita bid to compete in this year’s their National Basketball Associa- matters. He a flow of champion- Derby. iff keeps steady tournament tion starting February 27 series at Uline Arena at 8:30 Prospects were excellent for an ships coming back to Southern California each at the of o’clock. -

2011 National Club Cross Country Championships

Club Northwest • USATF Pacific Northwest • Pro-Motion Events Seattle Sports Commission • Seattle Parks & Recreation The Battle in Seattle 2011 National Club Cross Country Championships Jefferson Park Golf Course Seattle, Washington Saturday, December 10, 2011 LOCAL SPONSOR ADVERTISEMENT WELCOME FROM USA TRACK & FIELD We welcome you from your #1 fans! On behalf of the Long Distance Running Division, the Cross Country Council, and the Club Council, it is our pleasure to be in Seattle for the 14th edition of these championships held to determine the best club programs in the country. Under the able watch of our volunteer leadership and WELCOME TO THE NORTHWEST! Andy Martin and Jim Estes of the national staff, these championships have grown from the meager numbers We welcome you to the Puget Sound region! which greeted us in our early years to several recent years This is the eighth time a national cross country meet has of participation of over one thousand runners from across been held in the greater Seattle / Tacoma area: the nation. 1978 AAU Men’s 10k, West Seattle Golf Course Re-building the strength of our once-proud club system helps 1981 AAU Junior Men’s 8k, Green Lake USATF accomplish several goals: provide opportunities for 1981 AIAW Women, Tyee Valley Golf Course post-collegians to stay in the sport; coalesce activities in 1985 TAC Junior Olympics, Lower Woodland Park distance running into training groups; bring a team element 1989 USATF World Trials, Tyee Valley Golf Course to the sport which is widely successful in high schools and 1990 USATF World Trials, Tyee Valley Golf Course colleges across the country; and prove that our sport is one 1999 USATF World Trials, Spanaway Lake Golf Course for all ages. -

2021 : RRCA Distance Running Hall of Fame : 1971 RRCA DISTANCE RUNNING HALL of FAME MEMBERS

2021 : RRCA Distance Running Hall of Fame : 1971 RRCA DISTANCE RUNNING HALL OF FAME MEMBERS 1971 1972 1973 1974 1975 Bob Cambell Ted Corbitt Tarzan Brown Pat Dengis Horace Ashenfleter Clarence DeMar Fred Faller Victor Drygall Leslie Pawson Don Lash Leonard Edelen Louis Gregory James Hinky Mel Porter Joseph McCluskey John J. Kelley John A. Kelley Henigan Charles Robbins H. Browning Ross Joseph Kleinerman Paul Jerry Nason Fred Wilt 1976 1977 1978 1979 1980 R.E. Johnson Eino Pentti John Hayes Joe Henderson Ruth Anderson George Sheehan Greg Rice Bill Rodgers Ray Sears Nina Kuscsik Curtis Stone Frank Shorter Aldo Scandurra Gar Williams Thomas Osler William Steiner 1981 1982 1983 1984 1985 Hal Higdon William Agee Ed Benham Clive Davies Henley Gabeau Steve Prefontaine William “Billy” Mills Paul de Bruyn Jacqueline Hansen Gordon McKenzie Ken Young Roberta Gibb- Gabe Mirkin Joan Benoit Alex Ratelle Welch Samuelson John “Jock” Kathrine Switzer Semple Bob Schul Louis White Craig Virgin 1986 1987 1988 1989 1990 Nick Costes Bill Bowerman Garry Bjorklund Dick Beardsley Pat Porter Ron Daws Hugh Jascourt Cheryl Flanagan Herb Lorenz Max Truex Doris Brown Don Kardong Thomas Hicks Sy Mah Heritage Francie Larrieu Kenny Moore Smith 1991 1992 1993 1994 1995 Barry Brown Jeff Darman Jack Bacheler Julie Brown Ann Trason Lynn Jennings Jeff Galloway Norm Green Amby Burfoot George Young Fred Lebow Ted Haydon Mary Decker Slaney Marion Irvine 1996 1997 1998 1999 2000 Ed Eyestone Kim Jones Benji Durden Gerry Lindgren Mark Curp Jerry Kokesh Jon Sinclair Doug Kurtis Tony Sandoval John Tuttle Pete Pfitzinger 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 Miki Gorman Patti Lyons Dillon Bob Kempainen Helen Klein Keith Brantly Greg Meyer Herb Lindsay Cathy O’Brien Lisa Rainsberger Steve Spence 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 Deena Kastor Jenny Spangler Beth Bonner Anne Marie Letko Libbie Hickman Meb Keflezighi Judi St.