Karen Fang Hong Kong University Press the University of Hong Kong Pokfulam Road Hong Kong

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

See It Big! Action Features More Than 30 Action Movie Favorites on the Big

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE ‘SEE IT BIG! ACTION’ FEATURES MORE THAN 30 ACTION MOVIE FAVORITES ON THE BIG SCREEN April 19–July 7, 2019 Astoria, New York, April 16, 2019—Museum of the Moving Image presents See It Big! Action, a major screening series featuring more than 30 action films, from April 19 through July 7, 2019. Programmed by Curator of Film Eric Hynes and Reverse Shot editors Jeff Reichert and Michael Koresky, the series opens with cinematic swashbucklers and continues with movies from around the world featuring white- knuckle chase sequences and thrilling stuntwork. It highlights work from some of the form's greatest practitioners, including John Woo, Michael Mann, Steven Spielberg, Akira Kurosawa, Kathryn Bigelow, Jackie Chan, and much more. As the curators note, “In a sense, all movies are ’action’ movies; cinema is movement and light, after all. Since nearly the very beginning, spectacle and stunt work have been essential parts of the form. There is nothing quite like watching physical feats, pulse-pounding drama, and epic confrontations on a large screen alongside other astonished moviegoers. See It Big! Action offers up some of our favorites of the genre.” In all, 32 films will be shown, many of them in 35mm prints. Among the highlights are two classic Technicolor swashbucklers, Michael Curtiz’s The Adventures of Robin Hood and Jacques Tourneur’s Anne of the Indies (April 20); Kurosawa’s Seven Samurai (April 21); back-to-back screenings of Mad Max: Fury Road and Aliens on Mother’s Day (May 12); all six Mission: Impossible films -

Hole a Remediative Approach to the Filmmaking of the Coen Brothers

University of Dundee DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Going Down the 'Wabbit' Hole A Remediative Approach to the Filmmaking of the Coen Brothers Barrie, Gregg Award date: 2020 Link to publication General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 24. Sep. 2021 Going Down the ‘Wabbit’ Hole: A Remediative Approach to the Filmmaking of the Coen Brothers Gregg Barrie PhD Film Studies Thesis University of Dundee February 2021 Word Count – 99,996 Words 1 Going Down the ‘Wabbit’ Hole: A Remediative Approach to the Filmmaking of the Coen Brothers Table of Contents Table of Figures ..................................................................................................................................... 2 Declaration ............................................................................................................................................ -

The Whistleblowers

A U S F I L M Australian Familiarisation Event Mathew Tang Producer Mathew Tang began his career in 1989 and has since worked on over 30 feature films, covering various creative and production duties that include assistant directing, line-producing, writing, directing and producing. In 1999, Mathew debuted as a screenwriter on The Kid, a film that went on to win Best Supporting Actor and Actress in the Hong Kong Film Awards. In 2005, he wrote, edited and directed his debut feature B420 which received The Grand Prix Award at the 19th Fukuoka Asian Film Festival and Best Film at the 4th Viennese Youth International Film Festival in 2007. Mathew served as Associate Producer and Line Producer on Forbidden Kingdom and oversaw the Hollywood blockbuster’s entire production in China. In 2008 and 2009 he was Vice President of Celestial Pictures. From 2009- 2012, he was the Head of Productions at EDKO Films Ltd. In the summer of 2012, he founded Movie Addict Productions and the company produced four movies. Mathew is currently an Invited Executive Member of the Hong Kong Screenwriters’ Guild and a Panel Examiner of the Hong Kong Film Development Council. Johnny Wang Line Producer Johnny Wang started working for the movie industry in 1989 and by the year 2002, he started working at Paramount Studios on the project Tomb Raider 2 as production supervisor on location in Hong Kong. Since then, he has line produced 20 movies in Hong Kong, China and other locations around the world. Johnny has been an executive board member of the HKMPEA (Hong Kong Movie Production Executives Association) for more than four years. -

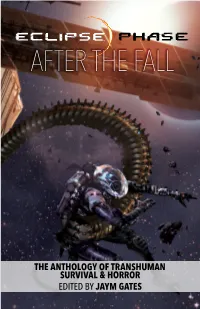

Eclipse Phase: After the Fall

AFTER THE FALL In a world of transhuman survival and horror, technology allows the re-shaping of bodies and minds, but also creates opportunities for oppression and puts the capa- AFTER THE FALL bility for mass destruction in the hands of everyone. Other threats lurk in the devastated habitats of the Fall, dangers both familiar and alien. Featuring: Madeline Ashby Rob Boyle Davidson Cole Nathaniel Dean Jack Graham Georgina Kamsika SURVIVAL &SURVIVAL HORROR Ken Liu OF ANTHOLOGY THE Karin Lowachee TRANSHUMAN Kim May Steven Mohan, Jr. Andrew Penn Romine F. Wesley Schneider Tiffany Trent Fran Wilde ECLIPSE PHASE 21950 Advance THE ANTHOLOGY OF TRANSHUMAN Reading SURVIVAL & HORROR Copy Eclipse Phase created by Posthuman Studios EDITED BY JAYM GATES Eclipse Phase is a trademark of Posthuman Studios LLC. Some content licensed under a Creative Commons License (BY-NC-SA); Some Rights Reserved. © 2016 AFTER THE FALL In a world of transhuman survival and horror, technology allows the re-shaping of bodies and minds, but also creates opportunities for oppression and puts the capa- AFTER THE FALL bility for mass destruction in the hands of everyone. Other threats lurk in the devastated habitats of the Fall, dangers both familiar and alien. Featuring: Madeline Ashby Rob Boyle Davidson Cole Nathaniel Dean Jack Graham Georgina Kamsika SURVIVAL &SURVIVAL HORROR Ken Liu OF ANTHOLOGY THE Karin Lowachee TRANSHUMAN Kim May Steven Mohan, Jr. Andrew Penn Romine F. Wesley Schneider Tiffany Trent Fran Wilde ECLIPSE PHASE 21950 THE ANTHOLOGY OF TRANSHUMAN SURVIVAL & HORROR Eclipse Phase created by Posthuman Studios EDITED BY JAYM GATES Eclipse Phase is a trademark of Posthuman Studios LLC. -

Bullet in the Head

JOHN WOO’S Bullet in the Head Tony Williams Hong Kong University Press The University of Hong Kong Pokfulam Road Hong Kong www.hkupress.org © Tony Williams 2009 ISBN 978-962-209-968-5 All rights reserved. No portion of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage or retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publisher. British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Printed and bound by Condor Production Ltd., Hong Kong, China Contents Series Preface ix Acknowledgements xiii 1 The Apocalyptic Moment of Bullet in the Head 1 2 Bullet in the Head 23 3 Aftermath 99 Appendix 109 Notes 113 Credits 127 Filmography 129 1 The Apocalyptic Moment of Bullet in the Head Like many Hong Kong films of the 1980s and 90s, John Woo’s Bullet in the Head contains grim forebodings then held by the former colony concerning its return to Mainland China in 1997. Despite the break from Maoism following the fall of the Gang of Four and Deng Xiaoping’s movement towards capitalist modernization, the brutal events of Tiananmen Square caused great concern for a territory facing many changes in the near future. Even before these disturbing events Hong Kong’s imminent return to a motherland with a different dialect and social customs evoked insecurity on the part of a population still remembering the violent events of the Cultural Revolution as well as the Maoist- inspired riots that affected the colony in 1967. -

Season Paul Rudd Talks Ant-Man and the Wasp

JULY 2018 | VOLUME 19 | NUMBER 6 Inside HENRY CAVILL NEVE CAMPBELL ANTOINE FUQUA BUG SEASON PAUL RUDD TALKS ANT-MAN AND THE WASP PUBLICATIONS MAIL AGREEMENT NO. 41619533 10 FUN FACTS ABOUT MAMMA MIA! HERE WE GO AGAIN, PAGE 24 CONTENTS JULY 2018 | VOL 19 | Nº6 COVER STORY 36 SUPERBUGS Feeling down after the events of Avengers: Infinity War? Paul Rudd, a.k.a. Ant-Man, LILLY. RUDD AND ’S EVANGELINE PAUL is here to lighten the load as he talks about his sequel, Ant-Man and the Wasp, which takes place before Infinity War. The affable actor keeps quiet PHOTO BY MICHAEL MULLER/MARCO GROB/©MARVEL STUDIOS PHOTO on the movie’s plot but opens AND THE ANT-MAN WASP up about working with co-star Evangeline Lilly and what makes Ant-Man so darn likable BY INGRID RANDOJA ON THE COVER: REGULARS 4 EDITOR’S NOTE 6 SNAPS 8 IN BRIEF 12 SPOTLIGHT CANADA 14 ALL DRESSED UP 16 IN THEATRES 40 CASTING CALL 44 RETURN ENGAGEMENT 46 CINEPLEX STORE 50 FINALLY… FEATURES 24 MORE 26 ON A MISSION 28 GOING UP 32 JUSTICE SERVED MAMMA MIA! Henry Cavill tells us about Skyscraper star Neve Campbell The Equalizer 2 director We count down 10 fascinating Mission: Impossible - Fallout says being a former dancer Antoine Fuqua talks about facts that set the stage for this and explains why doing stunts helped when it came to dealing with violence both month’s ABBA-riffic sequel on a Tom Cruise pic is such performing stunts in the on screen and in the real Mamma Mia! Here We Go Again good, scary fun Dwayne Johnson action pic communities where he films BY MARNI WEISZ BY MELISSA SHEASGREEN BY INGRID RANDOJA BY MARNI WEISZ JULY 2018 | CINEPLEX MAGAZINE | 3 EDITOR’S NOTE PUBLISHER SALAH BACHIR EDITOR MARNI WEISZ DEPUTY EDITOR INGRID RANDOJA CREATIVE DIRECTOR LUCINDA WALLACE GRAPHIC DESIGNER DARRYL MABEY VICE PRESIDENT, PRODUCTION SHEILA GREGORY CONTRIBUTORS MELISSA SHEASGREEN ADVERTISING SALES FOR CINEPLEX MAGAZINE IS HANDLED BY CINEPLEX MEDIA. -

HBO Documentary Explores Evolution of Gang Culture

HBO Documentary Explores Evolution of Gang Culture Written by Robert ID3265 Monday, 29 January 2007 05:04 - HBO Documentary ‘Bastards of the Party’ February 6th Raised in the Athens Park neighborhood of Los Angeles, Cle "Bone" Sloan was four years old when his father died, and 12 when he became a member of the Bloods. Now an inactive member of the notorious gang, Sloan looks back at the history of black gangs in his city and makes a powerful call for change in modern gang culture when his insightful documentary ‘BASTARDS OF THE PARTY’. Acclaimed feature film director Antoine Fuqua ("Training Day") produces along with Sloan, who also directs. Haunted by his involvement in the Bloods'' pervasive culture of violence, Sloan wanted to explore where it all began. In researching the subject, he discovered that the roots of black gangs were nurtured within a distinct political landscape. BASTARDS OF THE PARTY traces the development of black gangs in Los Angeles from the late 1940s, through the charged atmosphere of the ''60s and ''70s, to the breakdown of community in the ''80s and ''90s, and the brief truce between the Crips and Bloods that followed the Rodney King riots in 1992. Among the gangs that figure in the story are the Spook- hunters, Farmers, Slauscons, Businessmen and Gladiators. The documentary features interviews with past and current gang members from the Bloods and Crips; LA historian Mike Davis, whose book "City of Quartz" sparked Sloan's own project; former FBI agent Wes Swearingen; and Geronimo Pratt, the former Black Panther Party minister of defense, among others. -

Malcolm's Video Collection

Malcolm's Video Collection Movie Title Type Format 007 A View to a Kill Action VHS 007 A View To A Kill Action DVD 007 Casino Royale Action Blu-ray 007 Casino Royale Action DVD 007 Diamonds Are Forever Action DVD 007 Diamonds Are Forever Action DVD 007 Diamonds Are Forever Action Blu-ray 007 Die Another Day Action DVD 007 Die Another Day Action Blu-ray 007 Dr. No Action VHS 007 Dr. No Action Blu-ray 007 Dr. No DVD Action DVD 007 For Your Eyes Only Action DVD 007 For Your Eyes Only Action VHS 007 From Russia With Love Action VHS 007 From Russia With Love Action Blu-ray 007 From Russia With Love DVD Action DVD 007 Golden Eye (2 copies) Action VHS 007 Goldeneye Action Blu-ray 007 GoldFinger Action Blu-ray 007 Goldfinger Action VHS 007 Goldfinger DVD Action DVD 007 License to Kill Action VHS 007 License To Kill Action Blu-ray 007 Live And Let Die Action DVD 007 Never Say Never Again Action VHS 007 Never Say Never Again Action DVD 007 Octopussy Action VHS Saturday, March 13, 2021 Page 1 of 82 Movie Title Type Format 007 Octopussy Action DVD 007 On Her Majesty's Secret Service Action DVD 007 Quantum Of Solace Action DVD 007 Quantum Of Solace Action Blu-ray 007 Skyfall Action Blu-ray 007 SkyFall Action Blu-ray 007 Spectre Action Blu-ray 007 The Living Daylights Action VHS 007 The Living Daylights Action Blu-ray 007 The Man With The Golden Gun Action DVD 007 The Spy Who Loved Me Action Blu-ray 007 The Spy Who Loved Me Action VHS 007 The World Is Not Enough Action Blu-ray 007 The World is Not Enough Action DVD 007 Thunderball Action Blu-ray 007 -

East Bay Deputy Held in Drug Case Arrest Linked to Ongoing State Narcotics Agent Probe

Sunday, March 6, 2011 California’s Best Large Newspaper as named by the California Newspaper Publishers Association | $3.00 Gxxxxx• TOP OF THE NEWS Insight Bay Area Magazine WikiLeaks — 1 Newsom: Concerns Spring adventure World rise over S.F. office deal 1 Libya uprising: Reb- How Europe with donor. C1 tours from the els capture a key oil port caves in to U.S. 1 Shipping: Nancy Pelo- Galapagos to while state forces un- si extols the importance leash mortar fire. A5 pressure. F6 of local ports. C1 South Africa. 6 Sporting Green Food & Wine Business Travel 1 Scouting triumph: 1 Larry Goldfarb: Marin The Giants picked All about falafel County hedge fund manager Special Hawaii rapidly rising prospect who settled fraud charges Brandon Belt, right, — with three stretched the truth about section touts 147th in the ’09 draft. B1 recipes. H1 charitable donations. D1 Kailua-Kona. M1 RECOVERY East Bay deputy held in drug case Arrest linked to ongoing state narcotics agent probe By Justin Berton custody by agents representing CHRONICLE STAFF WRITER the state Department of Justice and the district attorney’s of- A Contra Costa County sher- fice. iff’s deputy has been arrested in Authorities did not elaborate connection with the investiga- on the details of the alleged tion of a state narcotics agent offenses, but a statement from who allegedly stole drugs from the Contra Costa County Sher- Michael Macor / The Chronicle evidence lockers, authorities iff’s Department said Tanabe’s Chris Rodriguez (4) of the Bay Cruisers shoots over Spencer Halsop (24) of the Utah Jazz said Saturday. -

Introduction

INTRODUCTION The wuxia film is the oldest genre in the Chinese cinema that has remained popular to the present day. Yet despite its longevity, its history has barely been told until fairly recently, as if there was some force denying that it ever existed. Indeed, the genre was as good as non-existent in China, its country of birth, for some fifty years, being proscribed over that time, while in Hong Kong, where it flowered, it was gen- erally derided by critics and largely neglected by film historians. In recent years, it has garnered a following not only among fans but serious scholars. David Bordwell, Zhang Zhen, David Desser and Leon Hunt have treated the wuxia film with the crit- ical respect that it deserves, addressing it in the contexts of larger studies of Hong Kong cinema (Bordwell), the Chinese cinema (Zhang), or the generic martial arts action film and the genre known as kung fu (Desser and Hunt).1 In China, Chen Mo and Jia Leilei have published specific histories, their books sharing the same title, ‘A History of the Chinese Wuxia Film’ , both issued in 2005.2 This book also offers a specific history of the wuxia film, the first in the English language to do so. It covers the evolution and expansion of the genre from its beginnings in the early Chinese cinema based in Shanghai to its transposition to the film industries in Hong Kong and Taiwan and its eventual shift back to the Mainland in its present phase of development. Subject and Terminology Before beginning this history, it is necessary first to settle the question ofterminology , in the process of which, the characteristics of the genre will also be outlined. -

1 Chinese Cinema Survey: 1980–Present Film S142 / Eall

CHINESE CINEMA SURVEY: 1980–PRESENT FILM S142 / EALL S258 Meeting Times: T,Th 1-2:50pm; Session B (July 12-August 13) Instructor: Xueli Wang Email: [email protected] Office Hours: by appointment Course Description: The past four decades have been extraordinarily fruitful for Chinese-language filmmaking. This course will survey key figures, movements, and trends in Sinophone cinema since 1980. Sessions will be structured around eleven films, each an entry point into a broader topic, such as the Fifth and Sixth Generation directors; the Hong Kong New Wave; New Taiwan Cinema; martial arts film; commercial blockbuster; and independent documentary. We will examine these films formally, through shot-by-shot analysis, as well as in relation to major social, political, and economic developments in recent Chinese history, such as the Cultural Revolution; Deng Xiaoping's economic reforms; the Hong Kong handover; the construction of the Three Gorges Dam; and the demolition and displacement of local communities. We will also consider pertinent questions of propaganda and censorship; aesthetics and politics; history and memory; transnational networks and audiences; and what constitutes "Chineseness" in a globalized world. Online Access: ● Seminars and in-class presentations will take place over Zoom. Our Zoom sessions will simulate a live classroom experience with everyone’s audio and video enabled. ● All assigned films will be available to watch remotely, either on Canvas or a streaming site. During some Zoom sessions, we will watch clips together alternating with discussion. ● All required readings and PowerPoint slides and film clips will be available on Canvas. ● Office hours will take place over Zoom, after class and by appointment. -

9. List of Film Genres and Sub-Genres PDF HANDOUT

9. List of film genres and sub-genres PDF HANDOUT The following list of film genres and sub-genres has been adapted from “Film Sub-Genres Types (and Hybrids)” written by Tim Dirks29. Genre Film sub-genres types and hybrids Action or adventure • Action or Adventure Comedy • Literature/Folklore Adventure • Action/Adventure Drama Heroes • Alien Invasion • Martial Arts Action (Kung-Fu) • Animal • Man- or Woman-In-Peril • Biker • Man vs. Nature • Blaxploitation • Mountain • Blockbusters • Period Action Films • Buddy • Political Conspiracies, Thrillers • Buddy Cops (or Odd Couple) • Poliziotteschi (Italian) • Caper • Prison • Chase Films or Thrillers • Psychological Thriller • Comic-Book Action • Quest • Confined Space Action • Rape and Revenge Films • Conspiracy Thriller (Paranoid • Road Thriller) • Romantic Adventures • Cop Action • Sci-Fi Action/Adventure • Costume Adventures • Samurai • Crime Films • Sea Adventures • Desert Epics • Searches/Expeditions for Lost • Disaster or Doomsday Continents • Epic Adventure Films • Serialized films • Erotic Thrillers • Space Adventures • Escape • Sports—Action • Espionage • Spy • Exploitation (ie Nunsploitation, • Straight Action/Conflict Naziploitation • Super-Heroes • Family-oriented Adventure • Surfing or Surf Films • Fantasy Adventure • Survival • Futuristic • Swashbuckler • Girls With Guns • Sword and Sorcery (or “Sword and • Guy Films Sandal”) • Heist—Caper Films • (Action) Suspense Thrillers • Heroic Bloodshed Films • Techno-Thrillers • Historical Spectacles • Treasure Hunts • Hong Kong • Undercover