Peri-Urban Interface Production System Research Natural Resources Systems Programme Baseline Study and Introductory Workshop

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

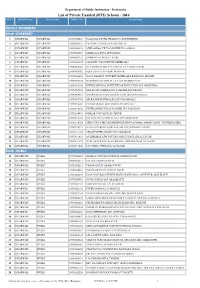

List of Private Unaided (RTE) Schools - 2016 Sl.No

Department of Public Instruction - Karnataka List of Private Unaided (RTE) Schools - 2016 Sl.No. District Name Block Name DISE Code School Name Distirct :DHARWAD Block :DHARWAD 1 DHARWAD DHARWAD 29090100407 NALANDA PATHA SHALE LPS AMMINBHAVI 2 DHARWAD DHARWAD 29090102302 PRATIJNA LPS DEVARAHUBBALLI 3 DHARWAD DHARWAD 29090102805 SHRI GARAG VIDYA MANDIR LPS GARAG 4 DHARWAD DHARWAD 29090102809 MAKKALA TOTA LPS GARAG 5 DHARWAD DHARWAD 29090103302 PADMARAJ LPS HALLIGERI 6 DHARWAD DHARWAD 29090103805 SADGURU VASUDEV HPS HEBBALLI 7 DHARWAD DHARWAD 29090105005 KALAKERI SANGEETA VIDYALAYA LPS KALKERI 8 DHARWAD DHARWAD 29090108002 IQRA TRUST LPS URDU MANSUR 9 DHARWAD DHARWAD 29090108405 NAVA BHARAT CONVENT MODEL HPS KANNADA MUGAD 10 DHARWAD DHARWAD 29090108704 RASTROTHAN VIDYALAYA LPS MUMMIGATTI 11 DHARWAD DHARWAD 29090108905 INTERNATIONAL INSTITUTE OF EDUCATION LPS NARENDRA 12 DHARWAD DHARWAD 29090109204 MALENADU SHIKSHANA SAMSTHE LPS NIGADI 13 DHARWAD DHARWAD 29090109903 DHARWAD INTERNATIONAL HPSL SHINGANAHALLI 14 DHARWAD DHARWAD 29090109904 SRI RAGHAVENDRA LPS SHINGANAHALLI 15 DHARWAD DHARWAD 29090110003 CHANDARAGI EDUCATION LPS SHIVALLI 16 DHARWAD DHARWAD 29090110206 VIVEKANAND VIDAY MANDIR LPS TADAKOD 17 DHARWAD DHARWAD 29090110403 OMKAR CONVENT LPS TEGUR 18 DHARWAD DHARWAD 29090110502 JNYANA JYOTI VIDYALAYA LPS TIMMAPUR 19 DHARWAD DHARWAD 29090110704 SHRI GURU VIRUPAKSHESHWAR HPS KANNADA AND ENGLISH UPPINBETAGERI 20 DHARWAD DHARWAD 29090110711 KALPAVRUKSHA GURUKULAM LPS UPPINABETAGERI 21 DHARWAD DHARWAD 29090111205 SWAMI VIVEKANAND LPS YADAWAD -

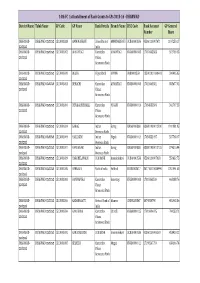

14Th FC 1St Installment of Basic Grants to Gps 2015-16

14th FC 1st Installment of Basic Grants to GPs 2015-16 - DHARWAD District Name Taluk Name GP Code GP Name Bank Details Branch Name IFSC Code Bank Account GP General Number Share DHARWAD- DHARWAD-ಾರಾಡ 1513001033 AMMINABHAVI Union Bank of AMMINABHAVI UCBA0000536 05360110007471 1197250.17 ಾರಾಡ India DHARWAD- DHARWAD-ಾರಾಡ 1513001002 ARAVATAGI Karnataka ARWATAGI KVGB0004003 17018063503 562769.13 ಾರಾಡ Vikasa Grameena Bank DHARWAD- DHARWAD-ಾರಾಡ 1513001020 BELUR Vijaya Bank KOTUR VIJB0001350 135001011000481 590485.85 ಾರಾಡ DHARWAD- DHARWAD-ಾರಾಡ 1513001013 BENACHI Karnataka ARWATAGI KVGB0004003 17018063581 388677.02 ಾರಾಡ Vikasa Grameena Bank DHARWAD- DHARWAD-ಾರಾಡ 1513001006 DEVARAHUBBALLI Karnataka NIGADI KVGB0004014 17054533500 341797.53 ಾರಾಡ Vikasa Grameena Bank DHARWAD- DHARWAD-ಾರಾಡ 1513001024 GARAG Indian Garag IOBA0000308 030801000012800 1011081.95 ಾರಾಡ Overseas Bank DHARWAD- DHARWAD-ಾರಾಡ 1513001009 HALLIGERI Indian Nigadi KVGB0004014 17054533497 587768.47 ಾರಾಡ Overseas Bank DHARWAD- DHARWAD-ಾರಾಡ 1513001017 HANGARAKI Indian Garag IOBA0000308 030801000012725 379516.94 ಾರಾಡ Overseas Bank DHARWAD- DHARWAD-ಾರಾಡ 1513001029 HAROBELAWADI UCO BANK Amminabhavi UCBA0000536 05360110007488 554632.75 ಾರಾಡ DHARWAD- DHARWAD-ಾರಾಡ 1513001035 HEBBALLI Bank of India Hebbali BKID0008417 841710110000999 1251991.60 ಾರಾಡ DHARWAD- DHARWAD-ಾರಾಡ 1513001010 HONNAPURA Karnataka Aravatagi KVGB0004003 17018063514 468188.76 ಾರಾಡ Vikasa Grameena Bank DHARWAD- DHARWAD-ಾರಾಡ 1513001016 KADABAGATTI Central Bank of Alanvar CBIN0280867 3074850790 482965.86 ಾರಾಡ India DHARWAD- -

Research Article URBAN WASTEWATER IRRIGATED AGRICULTURE AROUND HUBLI-DHARWAD, KARNATAKA, INDIA

International Journal of Agriculture Sciences ISSN: 0975-3710&E-ISSN: 0975-9107, Volume 9, Issue 19, 2017, pp.-4188-4192. Available online at http://www.bioinfopublication.org/jouarchive.php?opt=&jouid=BPJ0000217 Research Article URBAN WASTEWATER IRRIGATED AGRICULTURE AROUND HUBLI-DHARWAD, KARNATAKA, INDIA RADHIKA V. S.*, KULKARNI G. N. AND GAMANAGATTI A.B. Department of Agricultural Economics, College of Agriculture, University of Agricultural Sciences, Dharwad-580 005, Karnataka, India *Corresponding Author: [email protected] Received: March 17, 2017; Revised: April 03, 2017; Accepted: April 04, 2017; Published: April 24, 2017 Abstract- India will become a water stressed nation by 2020 as the average availability of water is reducing rapidly with the increasing population. Within the twin city of Hubli-Dharwad approximately 110 million l of wastewater is generated every day. The present study was done to decipher the Urban Wa stewater Irrigated Agriculture around Hubli-Dharwad, Karnataka, India using the primary data obtained by semi-structured interviews, participatory rural appraisal (PRA) technique and on-farm transect walks. Along the main Hubli wastewater nallas three distinct cropping systems are apparent: vegetable production; field crops with vegetables; and agroforestry. The perceptions of the farmers that they get more yields under sewage water irrigation compared to fresh water. Unregulated and continuous irrigation with wastewater also leads to soil clogging (sewage sickness), salinization and phytotoxicity. The treatment of sewage water to remove hazardous elements dissolved in it locally through socially acceptable, economically viable and cost-effective methods to sustain agricultural production, livelihoods systems and quality environment in the peri-urban areas is needed. -

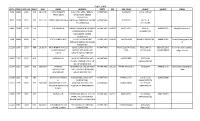

Hubballi Rural

¸ÀA¥ÀÄl -156 , 29 , 2021 ( 07, , ೧೯೪3) ¸ÀAaPÉ 111 Volume - 156 BENGALURU, THURSDAY, 29, JULY, 2021 (SHRAVANA ,07, SHAKAVARSHA, 1943) Issue 111 GOVERNMENT OF KARNATAKA No. RD 64 SSM 2019 Karnataka Government Secretariat, M.S. Building, Bengaluru, dt: 17.01.2020 N O T I F I C A T I O N In exercise of the powers conferred under section 5(2) of the Waqf Act, 1995, as amended during 2013 (27 of 2013) the Government of Karnataka, Minority Welfare Department has forwarded the proposals received from the Deputy Commissioner, Addl. Commissioner of Survey, Dharwad District, Dharwad to the Board in letter No.Wakf/CR/04/2019-20 dated: 11-09-2019. It is verified and approved by the Administrator, Karnataka State Board of Auqaf on 09-10-2019. The Govt. of Karnataka is hereby notify that the following immovable properties are Waqf properties. ¨sÁUÀ 4J PÀ£ÁðlPÀ gÁdå¥ÀvÀæ, , 29 , 2021 1275 Name of the District: DHARWAD Sub-Division: DHARWAD Name of the Taluk: HUBBALLI [RURAL] Location and details of waqf property Gross Administration waqf Name & Sunni Name & Annual by custom or Sl. Benefeciaries, Object of scheme address of the or City/ Sy.No./ Extent Value Year of creation of Waqf address of income settled by Remarks No. if any Waqf approved institution Shia Town/ CTS No. in Boundaries wakif of waqf court or by Board Village /Khata No. sq.ft (in Rs/-) hereditary 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 Ahale sunnath Gift by Jamath 3024 N – Gavthana Alli Sab Jumma GPC No. -

Of 426 AUTO YEAR IVPR SRL PAGE DOB NAME ADDRESS STATE PIN

Page 1 of 426 AUTO YEAR IVPR_SRL PAGE DOB NAME ADDRESS STATE PIN REG_NUM QUALIF MOBILE EMAIL 7356 1994S 2091 345 28.04.49 KRISHNAMSETY D-12, IVRI, QTRS, HEBBAL, KARNATAKA VCI/85/94 B.V.Sc./APAU/ PRABHODAS BANGALORE-580024 KARNATAKA 8992 1994S 3750 425 03.01.43 SATYA NARAYAN SAHA IVRI PO HA FARM BANGALORE- KARNATAKA VCI/92/94 B.V.Sc. & 24 KARNATAKA A.H./CU/66 6466 1994S 1188 295 DINTARAN PAL ANIMAL NUTRITION DIV NIANP KARNATAKA 560030 WB/2150/91 BVSc & 9480613205 [email protected] ADUGODI HOSUR ROAD AH/BCKVV/91 BANGALORE 560030 KARNATAKA 7200 1994S 1931 337 KAJAL SANKAR ROY SCIENTIST (SS) NIANP KARNATAKA 560030 WB/2254/93 BVSc&AH/BCKVV/93 9448974024 [email protected] ADNGODI BANGLORE 560030 m KARNATAKA 12229 1995 2593 488 26.08.39 KRISHNAMURTHY.R,S/ #1645, 19TH CROSS 7TH KARNATAKA APSVC/205/94,VCI/61 BVSC/UNI OF 080 25721645 krishnamurthy.rayakot O VEERASWAMY SECTOR, 3RD MAIN HSR 7/95 MADRAS/62 09480258795 [email protected] NAIDU LAYOUT, BANGALORE-560 102. 14837 1995 5242 626 SADASHIV M. MUDLAJE FARMS BALNAD KARNATAKA KAESVC/805/ BVSC/UAS VILLAGE UJRRHADE PUTTUR BANGALORE/69 DA KA KARANATAKA 11694 1995 2049 460 29/04/69 JAMBAGI ADIGANGA EXTENSION AREA KARNATAKA 591220 KARNATAKA/2417/ BVSC&AH 9448187670 shekharjambagi@gmai RAJASHEKHAR A/P. HARUGERI BELGAUM l.com BALAKRISHNA 591220 KARANATAKA 10289 1995 624 386 BASAVARAJA REDDY HUKKERI, BELGAUM DISTT. KARNATAKA KARSUL/437/ B.V.SC./GAS 9241059098 A.I. KARANATAKA BANGALORE/73 14212 1995 4605 592 25/07/68 RAJASHEKAR D PATIL, AMALZARI PO, BILIGI TQ, KARNATAKA KARSV/2824/ B.V.SC/UAS S/O DONKANAGOUDA BIJAPUR DT. -

Request for Proposal

REQUEST FOR PROPOSAL FOR DEVELOPMENT OF ‘SMART PARKING TOWER’ (MULTI LEVEL CAR PARKING CUM COMMERCIAL COMPLEX) THROUGH PUBLIC PRIVATE PARTNERSHIP (“PPP”) MODE ON DESIGN, BUILD, FINANCE, OPERATE AND TRANSFER (“DBFOT”) BASIS AT COURT CIRCLE, HUBBALLI REQUEST FOR PROPOSAL FOR DEVELOPMENT OF MULTI-LEVEL CAR PARKING ON DESIGN, BUILD, FINANCE, OPERATE AND TRANSFER (DBFOT) AT HUBBALLI Table of Contents DISCLAIMER ............................................................................................................................................... 3 Important Dates ....................................................................................................................................... 4 1. Invitation for Proposal: Brief Background .............................................................................................. 5 2. Project Background ................................................................................................................................. 6 2.1 Introduction ....................................................................................................................................... 6 2.2 Development Envisaged.................................................................................................................... 8 2.3 Concession period ............................................................................................................................. 9 2.4 Revenue Streams from the Project ................................................................................................. -

Survey on Spot Blotch Severity of Wheat in Northern Parts of Karnataka

Int.J.Curr.Microbiol.App.Sci (2019) 8(2): 1318-1330 International Journal of Current Microbiology and Applied Sciences ISSN: 2319-7706 Volume 8 Number 02 (2019) Journal homepage: http://www.ijcmas.com Original Research Article https://doi.org/10.20546/ijcmas.2019.802.154 Survey on Spot Blotch Severity of Wheat in Northern Parts of Karnataka R. Ashwini* and P.V. Patil Department of Plant Pathology, College of Agriculture, Dharwad, University of Agricultural Sciences, Dharwad-580 005, Karnataka, India *Corresponding author ABSTRACT K e yw or ds Survey and surveillance form the basis for any successful plant protection that Spot blotch, depends on early detection of disease followed by timely adoption of management Bipolaris measures. Spot blotch caused by Bipolaris sorokiniana is an important disease of sorokiniana, wheat gaining much importance in Karnataka because of the occurrence of severe Roving survey, Northern Karnataka outbreak every year. Intensive roving survey was conducted in wheat growing areas of Dharwad, Gadag, Belagavi, Bagalkote and Vijayapura districts of Article Info Karnataka, during rabi, 2017-18. Results revealed that there was very low severity Accepted: of spot blotch disease among various districts, taluks, villages surveyed in 12 January 2019 different wheat growing regions of Karnataka during rabi 2017-18. Available Online: 10 February 2019 Introduction cultivation wherein all three cultivated species, viz., Triticum aestivum L., T. durum Wheat (Triticum spp.; family: Poaceae; centre Shrank and T. dicoccum Desm. are grown in of origin: Abyssinia) the versatile cereal crop tropical climate, characterized by the is also described as “the shuffle of life” or prevalence of high temperature during the “king of cereals”. -

1995-96 and 1996- Postel Life Insurance Scheme 2988. SHRI

Written Answers 1 .DECEMBER 12. 1996 04 Written Answers (c) if not, the reasons therefor? (b) No, Sir. THE MINISTER OF STATE IN THE MINISTRY OF (c) and (d). Do not arise. RAILWAYS (SHRI SATPAL MAHARAJ) (a) No, Sir. [Translation] (b) Does not arise. (c) Due to operational and resource constraints. Microwave Towers [Translation] 2987 SHRI THAWAR CHAND GEHLOT Will the Minister of COMMUNICATIONS be pleased to state : Construction ofBridge over River Ganga (a) the number of Microwave Towers targated to be set-up in the country during the year 1995-96 and 1996- 2990. SHRI RAMENDRA KUMAR : Will the Minister 97 for providing telephone facilities, State-wise; of RAILWAYS be pleased to state (b) the details of progress achieved upto October, (a) whether there is any proposal to construct a 1906 against above target State-wise; and bridge over river Ganges with a view to link Khagaria and Munger towns; and (c) whether the Government are facing financial crisis in achieving the said target? (b) if so, the details thereof alongwith the time by which construction work is likely to be started and THE MINISTER OF COMMUNICATIONS (SHRI BENI completed? PRASAD VERMA) : (a) to (c). The information is being collected and will be laid on the Table of the House. THE MINISTER OF STATE IN THE MINISTRY OF RAILWAYS (SHRI SATPAL MAHARAJ) : (a) No, Sir. [E nglish] (b) Does not arise. Postel Life Insurance Scheme Railway Tracks between Virar and Dahanu 2988. SHRI VIJAY KUMAR KHANDELWAL : Will the Minister of COMMUNICATIONS be pleased to state: 2991. SHRI SURESH PRABHU -

District Census Handbook, Dharwad, Part XII-A, Series-11

CENSUS OF INDIA 1991 Series -11 KARNATAKA DISTRICT CENSUS HANDBOOK DHAR\VAD DISTRICT PART XII-A "IU.AGE ANHTOWN DIRELJORY SOBIIA NAMBISAN DH-ector of Census Operations, Kurnataka CONTENTS Page No. FOREWORD vii-viii PREFACE lX-X IMPORTANT STATISTICS ANALYTICAL NOTE Section-I - VHl&lge DiI'cctm'Y Explanatory Notc Alphabelical List of Villages - Bpdgi C.O.Blm:k Village Directory Statemcnt - B).tdgi C.D.Blud. Alphabetical List of Villages - Dhafwad CoD. Rlock Village Dircctory Statemcnt - Dharwad C.D.Block Alphahctical Liht of Villagch - (jadag C.O.BlI)(:k Village Directory Statement - Gadag CD.Block ()X- 105 Alphabetical Lihl of Villages - Hallgal C.D.Bhld: )1)1)- I 12 Village Directory Statement - Hangal CD.Block 11-1-1-11 Alphabetical Liht of Villages - Ha .... eri C.D.Block 145-147 Village Directory Stah:mcnl - 11a\L~ri C.D.Blod. 1-1X- J(,.1 Alphabetical Lihl of Vilbgl.: .... - } lirdcr lit' C.D.Block 1(,7-170 Village Directory Slal<.:m..:nl - I-lird. ..:rur C.D.BhK'1-.. 11'2-1:-;1) Alphabetical List of Villageh - lillbli C.D.BhlCk 1'J.1-194 ViI1age Directory Slat<.:ment - Hubli C.D.Block 1')(>-205 Alphabetical Liht of Villages - Kalg:h;tlgi C.D.Block 2()')- 21 I Village Dircctory Statcment - K4Ilghatgi CO.Block 212-225 Alphabclit'al List of Villages - K lInd;I~()1 CD.Block 22()-23() Village Directory Stat<.:ml'nt - Kundagul C.D.Block Alphabetical List of Villageh - MlInd,lrgi CD.B1o,:h Village Directory Statcl1ll:nt - l\lulllbrgi CO.Blnd P"g_L' l'< ll. Alphahctical Li~t 01" Villages - N :1I·g.und C [). -

In the High Court of Karnataka Dharwad Bench

IN THE HIGH COURT OF KARNATAKA DHARWAD BENCH DATED THIS THE 10 T H DAY OF JUNE 2015 BEFORE THE HON’BLE MRS. JUSTICE S. SUJATHA R.F.A.NO.4018/2012 BETWEEN: 1. DEMAWWA W/O. MALLAPPA KADASIDDANNAVAR AGE: 55 YEARS, OCC: AGRICULTURE, R/O. GOVANAKOPPA, TQ: BAILHONGAL, DIST: BELGUAM. 2. KALLAWWA W/O. BALAPPA KOLLI AGE: 53 YEARS, OCC: AGRICULTURE, R/O. GOVANAKOPPA, NOW RESIDING AT RAMAPUR SITE, SOUNDATTI DIST: BELGAUM. .. APPELLANTS (BY SRI MALLIKARJUNSWAMY B HIREMATH, ADVOCATE.) AND: 1. MANJUNATH BALAPPA NORAJAPPANAVAR AGE: 28 YEARS, OCC: AGRICULTURE, R/O. GOVANAKOPPA, TQ: BAILHONGAL, NOW RESIDING AT: BANKAPUR, TQ: SHIGGAON, DIST: HAVERI. 2. NINGAWWA W/O. BALAPPA NORAJAPPANAVAR AGE: 54 YEARS, OCC: AGRICULTURE, R/O. GOVANAKOPPA, TQ: BAILHONGAL, NOW RESIDING AT: BANKAPUR, TQ: SHIGGAON, DIST: HAVERI. 3. BALAPPA BIMAPPA NORAJAPPANAVAR AGE: 59 YEARS, OCC: AGRICULTURE, 2 R/O. GOVANAKOPPA, TQ: BAILHONGAL, DIST: BELGAUM. 4. SUNANADA D/O. BHIMAPPA GORAVANAKOLLA FALSELY CALLING HERSELF AS SMT. SUNANDA W/O. BALAPPA NORAJAPPNAVAR AGE: 49 YEARS, OCC: HOUSEHOLD R/O. KARIKATTI, NOW AT, GOVANAKOPPA, TQ: BAILHONGAL, DIST: BELGAUM. 5. GURURAJ S/O. SUNANDA GORAVANAKOLLA FALSELY CALLING HIMSELF AS GURURAJ S/O.BALAPPA NORAJAPPANAVAR AGED ABOUT 24 YEARS, OCC: STUDENT, R/O. KARIKATTI, TQ: SAUNDATTI, DIST: BELGAUM. 6. DEVARAJ S/O. SUNANDA GORAVANAKOLLA FALSELY CALLING HIMSELF AS DEVARAJ S/O. BALAPPA NORAJAPPNAVAR AGE: 20 YEARS, OCC: AGRICULTURE, R/O. KARIKATTI, NOW AT GOVANAKOPPA, TQ: BAILHONGAL, DIST: BELGAUM. 7. BHARATI D/O. SUNANDA GORAVANAKOLLA FALSELY CALLING HERSELF AS BHARATI D/O. BALAPPA NORAJAPPNAVAR AGE: 28 YEARS, OCC: HOUSEHOLD WORK R/O. KARIKATTI, NOW AT GOVANAKOPPA TQ: BAILHONGAL, DIST: BELGAUM. -

Unpaid Dividend-17-18-I3 (PDF)

Note: This sheet is applicable for uploading the particulars related to the unclaimed and unpaid amount pending with company. Make sure that the details are in accordance with the information already provided in e-form IEPF-2 CIN/BCIN L72200KA1999PLC025564 Prefill Company/Bank Name MINDTREE LIMITED Date Of AGM(DD-MON-YYYY) 17-JUL-2018 Sum of unpaid and unclaimed dividend 696104.00 Sum of interest on matured debentures 0.00 Sum of matured deposit 0.00 Sum of interest on matured deposit 0.00 Sum of matured debentures 0.00 Sum of interest on application money due for refund 0.00 Sum of application money due for refund 0.00 Redemption amount of preference shares 0.00 Sales proceed for fractional shares 0.00 Validate Clear Proposed Date of Investor First Investor Middle Investor Last Father/Husband Father/Husband Father/Husband Last DP Id-Client Id- Amount Address Country State District Pin Code Folio Number Investment Type transfer to IEPF Name Name Name First Name Middle Name Name Account Number transferred (DD-MON-YYYY) 49/2 4TH CROSS 5TH BLOCK MIND00000000AZ00 Amount for unclaimed and A ANAND NA KORAMANGALA BANGALORE INDIA Karnataka 560095 54.00 23-May-2025 2539 unpaid dividend KARNATAKA 69 I FLOOR SANJEEVAPPA LAYOUT MIND00000000AZ00 Amount for unclaimed and A ANTONY FELIX NA MEG COLONY JAIBHARATH NAGAR INDIA Karnataka 560033 72.00 23-May-2025 2646 unpaid dividend BANGALORE ROOM NO 6 G 15 M L CAMP 12044700-01567454- Amount for unclaimed and A ARUNCHETTIYAR AKCHETTIYAR INDIA Maharashtra 400019 10.00 23-May-2025 MATUNGA MUMBAI MI00 unpaid -

Tank Information System Map of Bailhongala Taluk, Belagavi District

Tank Information System Map of Bailhongala Taluk, Belagavi District. Sunakumpi µ Mastamaradi 26719 1:110,300 Hoskoti 2178 2179 Vannur Gajaminhal 2301 2177 Legend 2176 Hanabar Hatti Drainage 19563 Mekalmaradi Mohare Ujjanatti Deshanur Mallapur Kariyat Nesargi District Road Koldur 19562 Nesargi Kalkuppi National Highway Somanatti 2452 State Highway Hogarti Koldur Madanbhavi Hanamana Hatti Taluk Boundary Mattikoppa Sutagatti Muraki Bhavi District Boundary Yaraguddi Lakkundi State Boundary Bairanatti Hannikeri 2441 Village Boundary Nagnur Hiremele Marikatti Jakkanaikanakoppa 18984 Bhavihal Pularkoppa Bailwad Bail Hongal (TMC) Chivatagundi Yaragoppa Ganikoppa Shigihalli Kariyat Sampagaon 18985 Navalgatti 31000 Bailhongal (Rural) 26762 2442 Tigadi Sanikoppa Giriyal Kariyat Bagewadi 19055 18988 2961 18986 Anigol Sampagaon (Bailhongal) 2130 Devalapur Benachinamardi 18987 Korvikoppa Yaradal Amatur Kallur Chick-Bagewadi2962 18970 19020 19054 Wakkund 2967 Mugabasav Mardinagalapur 2443 Pattihal Kariyat Sampagaon Bevinkoppa Chikkmulakur Hiremulakur Budihal Gaddikurvinkoppa 2969 Neginhal Araw alli 19021 19022 19023 Jalikoppa Lingadahalli TankInformation_OwnershipWise Kesarkoppa 2145 19024 19043 2970 2444 Garjur 19044 Kuragund Kenganoor Single Ownership 19047 Holihosur 19049 2971 Sangolli 19048 19053 19050 19052 Gudadur M.K.Hubli Belawadi KFD (4) 19051 Udikeri Holinagalapur 2933 18978 18966 2950 18960 Savatagi 2934 2938 2930 2931 MI (23) Amarapur Turamari 18956 18937 2935 Kulamanatti Pattihal K.B. 2125 2897 18967 2901 18980 2124 2952 2942 18940 Dodawad