At Chester Zoo Peter Watson Mammal Keeper, Chester Zoo [email protected]

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

VII. Bodies, Institutes and Centres

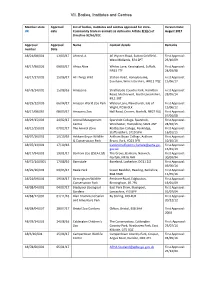

VII. Bodies, Institutes and Centres Member state Approval List of bodies, institutes and centres approved for intra- Version Date: UK date Community trade in animals as defined in Article 2(1)(c) of August 2017 Directive 92/65/EEC Approval Approval Name Contact details Remarks number Date AB/21/08/001 13/03/17 Ahmed, A 46 Wyvern Road, Sutton Coldfield, First Approval: West Midlands, B74 2PT 23/10/09 AB/17/98/026 09/03/17 Africa Alive Whites Lane, Kessingland, Suffolk, First Approval: NR33 7TF 24/03/98 AB/17/17/005 15/06/17 All Things Wild Station Road, Honeybourne, First Approval: Evesham, Worcestershire, WR11 7QZ 15/06/17 AB/78/14/002 15/08/16 Amazonia Strathclyde Country Park, Hamilton First Approval: Road, Motherwell, North Lanarkshire, 28/05/14 ML1 3RT AB/29/12/003 06/04/17 Amazon World Zoo Park Watery Lane, Newchurch, Isle of First Approval: Wight, PO36 0LX 15/06/12 AB/17/08/065 08/03/17 Amazona Zoo Hall Road, Cromer, Norfolk, NR27 9JG First Approval: 07/04/08 AB/29/15/003 24/02/17 Animal Management Sparsholt College, Sparsholt, First Approval: Centre Winchester, Hampshire, SO21 2NF 24/02/15 AB/12/15/001 07/02/17 The Animal Zone Rodbaston College, Penkridge, First Approval: Staffordshire, ST19 5PH 16/01/15 AB/07/16/001 10/10/16 Askham Bryan Wildlife Askham Bryan College, Askham First Approval: & Conservation Park Bryan, York, YO23 3FR 10/10/16 AB/07/13/001 17/10/16 [email protected]. First Approval: gov.uk 15/01/13 AB/17/94/001 19/01/17 Banham Zoo (ZSEA Ltd) The Grove, Banham, Norwich, First Approval: Norfolk, NR16 -

Verzeichnis Der Europäischen Zoos Arten-, Natur- Und Tierschutzorganisationen

uantum Q Verzeichnis 2021 Verzeichnis der europäischen Zoos Arten-, Natur- und Tierschutzorganisationen Directory of European zoos and conservation orientated organisations ISBN: 978-3-86523-283-0 in Zusammenarbeit mit: Verband der Zoologischen Gärten e.V. Deutsche Tierpark-Gesellschaft e.V. Deutscher Wildgehege-Verband e.V. zooschweiz zoosuisse Schüling Verlag Falkenhorst 2 – 48155 Münster – Germany [email protected] www.tiergarten.com/quantum 1 DAN-INJECT Smith GmbH Special Vet. Instruments · Spezial Vet. Geräte Celler Str. 2 · 29664 Walsrode Telefon: 05161 4813192 Telefax: 05161 74574 E-Mail: [email protected] Website: www.daninject-smith.de Verkauf, Beratung und Service für Ferninjektionsgeräte und Zubehör & I N T E R Z O O Service + Logistik GmbH Tranquilizing Equipment Zootiertransporte (Straße, Luft und See), KistenbauBeratung, entsprechend Verkauf undden Service internationalen für Ferninjektionsgeräte und Zubehör Vorschriften, Unterstützung bei der Beschaffung der erforderlichenZootiertransporte Dokumente, (Straße, Vermittlung Luft und von See), Tieren Kistenbau entsprechend den internationalen Vorschriften, Unterstützung bei der Beschaffung der Celler Str.erforderlichen 2, 29664 Walsrode Dokumente, Vermittlung von Tieren Tel.: 05161 – 4813192 Fax: 05161 74574 E-Mail: [email protected] Str. 2, 29664 Walsrode www.interzoo.deTel.: 05161 – 4813192 Fax: 05161 – 74574 2 e-mail: [email protected] & [email protected] http://www.interzoo.de http://www.daninject-smith.de Vorwort Früheren Auflagen des Quantum Verzeichnis lag eine CD-Rom mit der Druckdatei im PDF-Format bei, welche sich großer Beliebtheit erfreute. Nicht zuletzt aus ökologischen Gründen verzichten wir zukünftig auf eine CD-Rom. Stattdessen kann das Quantum Verzeichnis in digitaler Form über unseren Webshop (www.buchkurier.de) kostenlos heruntergeladen werden. Die Datei darf gerne kopiert und weitergegeben werden. -

ATIC0943 {By Email}

Animal and Plant Health Agency T 0208 2257636 Access to Information Team F 01932 357608 Weybourne Building Ground Floor Woodham Lane www.gov.uk/apha New Haw Addlestone Surrey KT15 3NB Our Ref: ATIC0943 {By Email} 4 October 2016 Dear PROVISION OF REQUESTED INFORMATION Thank you for your request for information about zoos which we received on 26 September 2016. Your request has been handled under the Freedom of Information Act 2000. The information you requested and our response is detailed below: “Please can you provide me with a full list of the names of all Zoos in the UK. Under the classification of 'Zoos' I am including any place where a member of the public can visit or observe captive animals: zoological parks, centres or gardens; aquariums, oceanariums or aquatic attractions; wildlife centres; butterfly farms; petting farms or petting zoos. “Please also provide me the date of when each zoo has received its license under the Zoo License act 1981.” See Appendix 1 for a list that APHA hold on current licensed zoos affected by the Zoo License Act 1981 in Great Britain (England, Scotland and Wales), as at 26 September 2016 (date of request). The information relating to Northern Ireland is not held by APHA. Any potential information maybe held with the Department of Agriculture, Environment and Rural Affairs Northern Ireland (DAERA-NI). Where there are blanks on the zoo license start date that means the information you have requested is not held by APHA. Please note that the Local Authorities’ Trading Standard departments are responsible for administering and issuing zoo licensing under the Zoo Licensing Act 1981. -

British Veterinary Zoological Society

British Veterinary Zoological Sociey Proceedings November 2007 British Veterinary Zoological Society Proceedings of the November Meeting 2007 10 th and 11 th November, 2007 The University of Nottingham School of Veterinary Medicine and Science Recent Advances in Comparative Medicine Proceedings Editor: Victoria Roberts British Veterinary Zoological Sociey Proceedings November 2007 BVZS GUIDELINES FOR MEETING ABSTRACTS PLEASE NOTE : From the November 2007 meeting all abstracts and extended abstracts will be linked to CABI. This is an important step in helping the Society and members work reach a wider audience. While the society encourages authors to include as much relevant data as possible, it is the author’s own responsibility to restrict their data as necessary in order not to prejudice any future peer-reviewed publications they may have planned. While previous humorous biographies have been included, inline with the links with CABI, please adhere to the biography guidelines and keep these to a professional nature. At present BVZS meetings and abstracts are NOT peer-reviewed. Submissions should preferably be in word (.doc) format, 12 font Times New Roman, single line spacing, not justified. Biography: This should include the author’s qualifications and institution/ practice/ affiliations, as well as a summary of any particular achievements, career, highlights, or relevant current projects. Please keep the biography to a professional nature. Maximum of 100 words. Title: Submission should include a title of not more than 15 words, and the names, qualifications and affiliation/ institution of each author. Abstracts: Abstracts should be a minimum of 200 words, and a maximum of 750 words. A reference list may also be included. -

Kruger National Park Elephant Management Plan

Elephant Management Plan Kruger National Park 2013-2022 Scientific Services November 2012 Contact details Mr Danie Pienaar, Head of Scientific Services, SANParks, Skukuza, 1350, South Africa Email: [email protected], Tel: +27 13 735 4000 Elephant Management Kruger Authorisation This Elephant Management Plan for the Kruger National Park was compiled by Scientific Services and the Kruger Park Management of SANParks. The group represented several tiers of support and management services in SANParks and consisted of: Scientific Services Dr Hector Magome Managing Executive: Conservation Services Dr Peter Novellie Senior General Manager: Conservation Services Dr Howard Hendricks General Manager: Policy and Governance Mr Danie Pienaar Senior General Manager: Scientific Services Dr Stefanie Freitag-Ronaldson General Manager: Scientific Services Savanna & Arid Nodes Dr Sam Ferreira Scientist: Large Mammal Ecology Kruger Park Management Mr Phin Nobela Senior Manager: Conservation Management Mr Nick Zambatis Manager: Conservation Management Mr Andrew Desmet Manager: Guided Activities and Conservation Interpretation Mr Albert Machaba Regional Ranger: Nxanatseni North Mr Louis Olivier Regional Ranger: Nxanatseni South Mr Derick Mashale Regional Ranger: Marula North Mr Mbongeni Tukela Regional Ranger: Marula South Ms Sandra Basson Section Ranger: Pafuri Mr Thomas Mbokota Section Ranger: Punda Maria Mr Stephen Midzi Section Ranger: Shangoni Ms Agnes Mukondeleli Section Ranger: Vlakteplaas Mr Marius Renkin Section Ranger: Shingwedzi Ms Tinyiko -

British Veterinary Zoological Society

British Veterinary Zoological Society Proceedings of the Autumn Meeting 2014 7 - 9 November, 2014 Lancaster University Management School and Blackpool Zoo INVERTEBRATES AND MEGAVERTEBRATES – VETERINARY ADVANCES Editors: Fieke Molenaar and Mark Stidworthy 0 BVZS AUTUMN MEETING 2014 British Veterinary Zoological Society BVZS is the specialist division of the British Veterinary Association (BVA) recognised as having responsibility for exotic pets, companion avian species and zoo animals. Founded in 1961, the BVZS nowadays has an international membership and finds itself involved in almost every aspect of the care and welfare of exotic pets, zoo animals and wildlife. The aims of the society are to promote the advancement of veterinary knowledge and skill in the maintenance of the health and welfare of non-domesticated animals and to encourage proper housing and conditions for such animals; to encourage full use of veterinary services by wild animal establishments and by the owners of exotic animals; to promote the international exchange of veterinary knowledge of non- domesticated animals. Information to the membership is provided by: Twice-yearly scientific meetings held at different venues throughout the UK e.g. university veterinary field stations and zoological collections. Proceedings from each of these meetings are published with hard copy for attending delegates and a CD with all Proceedings, 2001-2014, for all other members For 6 years BVZS held a Satellite Day at BSAVA in Birmingham. All details of this along with Proceedings are -

Whipsnade Is  Team Jacobâ

PRLog - Global Press Release Distribution Whipsnade is ‘Team Jacob’ ZSL Whipsnade Zoo has introduced some new blood to its adoption scheme for Halloween, with a storybook-inspired mystical animal…Jacob the wolf. Oct. 22, 2010 - PRLog -- Named after the Native-American werewolf character in Stephanie Meyer’s ‘Twilight’ series, Whipsnade’s Jacob may not be a mythical creature (that we know of…) but he is eerily similar to his Twilight namesake with his boyish charms and loyal personality. Part of the pack of European grey wolves that call the Zoo home, Jacob the wolf is the alpha-male of the group, with his very own ‘Bella’ in the form of the beautiful female Ophelia. Luckily at Whipsnade he has no vampires to compete with – but he still enjoys asserting his dominance with his impressive howling skills… ‘Twi-hards’ will love the opportunity to adopt their very own Jacob, which will be on sale from Monday 25 October. For the great value price of £24, adopters get a free ticket to visit ZSL Whipsnade Zoo to see him, a subscription to ZSL’s Wild About magazine and regular email updates from Jacob’s keepers. As ZSL Whipsnade Zoo is part of the Zoological Society of London, an international animal conservation charity, adopters of Jacob will be helping to support wildlife around the world. - ENDS - Notes to Editors For more information please contact Rebecca Smith at [email protected] or on 0207 449 6236 High resolution images are available on request B-Roll footage available on request Howling sound effects available on request ZSL Founded in 1826, the Zoological Society of London (ZSL) is an international scientific, conservation and educational charity: our key role is the conservation of animals and their habitats. -

Animal Careers

Animal Careers This pack is for people who are interested or researching animal careers, with a focus on wild animals and conservation. Contents Contents Page The Animal Industry 1 Role of Zoos in the 21st Century 2 Staff at Colchester Zoo 3 Conservationist 8 Animal Keeper Job Profile 9 Learning Officer Job Profile 10 Wildlife Ranger Job Profile 11 Skills and Attributes 12 Qualifications 13 Membership Organisations 15 Gaining Experience 16 Seasonal Work 17 Additional Skills 18 Where to Find Jobs 19 Day in the Life of a Tiger Keeper 21 Points to Remember 22 The Animal Industry The animal industry is part of the larger sector of the environmental and land-based industry, which includes 230,000 business across the U.K., employing around 1,126,000 people and over 500,000 volunteers. This information pack will focus on the zoological sector. Within the UK ,there are 350 zoo licences, which cover zoos, as well as safari parks, aquaria and bird gardens. Collectively they employ approximately 3,000 full time workers. The main job roles in the zoological sector are animal keeping, veterinary work, conservation, research and educational work. It is important to remember these roles are linked and not exclusive from each other. For example, an animal keeper will also be part of conservation, research and education work, as well as limited veterinary work in some cases. 1 Roles of Zoos in the 21st Century Zoo are now more than just a good day out to see animals, zoo have a role to play in education, conservation and research. -

Activity Pack: African Animals

Activity Pack: African Animals This pack is designed to provide teachers with information to help you lead a trip to Colchester Zoo focusing on African Animals How to Use this Pack: This African Animal Tour Guide pack was designed to help your students learn about African animals and prepare for a trip to Colchester Zoo. The pack starts with suggested African animals to visit at Colchester Zoo including a map of where to see them and which encounters/feeds to attend. The next section contains fact sheets about these animals. This includes general information about the type of animal (e.g. where they live, what they eat, etc.) and specific information about individuals at Colchester Zoo (e.g. their names, how to tell them apart, etc.). This information will help you plan your day, and your route around the zoo to see the most African Animals. We recommend all teachers read through this pack and give copies to adult helpers visiting with your school trip. The rest of the pack is broken into “Pre-Trip”, “At the Zoo”, and “Post-Trip”. Each of these sections start with ideas to help teachers think of ways to relate African animals to other topics. There are also a variety of pre-made activities and worksheets included in this pack. Activities are typically hands on ‘games’ that introduce and reinforce concepts. Worksheets are typically paper hand-outs teachers can photocopy and have pupils complete independently. Teachers can pick and choose which they want to use since all the activities/worksheets can be used independently (you can just use one worksheet if you wish; you don’t need to complete the others). -

In Our Hands: the British and UKOT Species That Large Charitable Zoos & Aquariums Are Holding Back from Extinction (AICHI Target 12)

In our hands: The British and UKOT species that Large Charitable Zoos & Aquariums are holding back from extinction (AICHI target 12) We are: Clifton & West of England Zoological Society (Bristol Zoo, Wild Places) est. 1835 Durrell Wildlife Conservation Trust (Jersey Zoo) est. 1963 East Midland Zoological Society (Twycross Zoo) est. 1963 Marwell Wildlife (Marwell Zoo) est. 1972 North of England Zoological Society (Chester Zoo) est. 1931 Royal Zoological Society of Scotland (Edinburgh Zoo, Highland Wildlife Park) est. 1913 The Deep est. 2002 Wild Planet Trust (Paignton Zoo, Living Coasts, Newquay Zoo) est. 1923 Zoological Society of London (ZSL London Zoo, ZSL Whipsnade Zoo) est. 1826 1. Wildcat 2. Great sundew 3. Mountain chicken 4. Red-billed chough 5. Large heath butterfly 6. Bermuda skink 7. Corncrake 8. Strapwort 9. Sand lizard 10. Llangollen whitebeam 11. White-clawed crayfish 12. Agile frog 13. Field cricket 14. Greater Bermuda snail 15. Pine hoverfly 16. Hazel dormouse 17. Maiden pink 18. Chagos brain coral 19. European eel 2 Executive Summary: There are at least 76 species native to the UK, Crown Dependencies, and British Overseas Territories which Large Charitable Zoos & Aquariums are restoring. Of these: There are 20 animal species in the UK & Crown Dependencies which would face significant declines or extinction on a global, national, or local scale without the action of our Zoos. There are a further 9 animal species in the British Overseas Territories which would face significant declines or extinction without the action of our Zoos. These species are all listed as threatened on the IUCN Red List. There are at least 19 UK animal species where the expertise of our Zoological Institutions is being used to assist with species recovery. -

See the Light Inside Hellabrun Zoo’S Discovery Cave

QUARTERLY PUBLICATION OF THE EUROPEAN ASSOCIATION OF ZOOS AND AQUARIA WINTERZ 2016 OO QUARIAISSUE 95 SEE THE LIGHT INSIDE HELLABRUN ZOO’S DISCOVERY CAVE To Russia with love REINTRODUCING THE PERSIAN LEOPARD 1 1 Majestic markhors AN EEP UPDATE FROM HELSINKI ZOO Contents Zooquaria Winter 2016 14 16 26 4 From the Director’s chair 18 Interview Our Director reports from the IUCN World Zooquaria talks to the outgoing and new Chairs of Conservation Congress the IUCN Species Survival Commission, Simon Stuart and Jon Paul Rodriguez 5 Noticeboard News from the world of conservation 21 Endangered species A creative solution that is helping to save the white- 6 Births & hatchings footed tamarin Magpies, foxes and turaco join the list of breeding successes 22 Conservation partners The benefits of collaboration between EAZA and 8 EAZA Annual Conference ALPZA EAZA’s annual conference is defined by its optimism for the future 23 EEP report Helsinki Zoo reports on the status and future of its 10 WAZA Conference Markhors EEP Why zoos and aquariums must be agents for change 24 Horticulture 11 EU Zoos Directive Planting ideas and solutions in action at Dublin Zoo How EAZA Members can take part in defining the future of the EU Zoos Directive. 26 Exhibits How the Discovery Cave at Hellabrun Zoo is helping 12 Campaigns visitors to overcome their phobias The Let It Grow campaign can help to demonstrate the importance of conserving local species 28 Education Can television and social media offer the same 14 Breeding programmes educational experience as a visit to the zoo? Reintroducing the Persian Leopard in the Caucasus 30 Resources 16 Conservation A visit to the ZSL Library will prove both informative How a combination of conservation initiatives and and inspiring research projects have helped to save the white stork Zooquaria EDITORIAL BOARD: EAZA Executive Office, PO Box 20164, 1000 HD Amsterdam, The Netherlands. -

Danish Zoo Defends Lion Killing After Giraffe Cull 26 March 2014, by Jan M

Danish zoo defends lion killing after giraffe cull 26 March 2014, by Jan M. Olsen "Furthermore we couldn't risk that the male lion mated with the old female as she was too old to be mated with again due to the fact that she would have difficulties with birth and parental care of another litter," the zoo said. The cubs were also put down because they were not old enough to fend for themselves and would have been killed by the new male lion anyway, officials said. Zoo officials hope the new male and two females born in 2012 will form the nucleus of a new pride. They said the culling "may seem harsh, but in nature is necessary to ensure a strong pride of This is a Sunday, Feb. 9, 2014 file photo of the carcass lions with the greatest chance of survival." of Marius, a male giraffe, as it is eaten by lions after he was put down in Copenhagen Zoo . The zoo that faced In February, the zoo faced protests and even death protests for killing a healthy giraffe to prevent inbreeding threats after it killed a 2-year-old giraffe, citing the says it has put down four lions, including two cubs, to need to prevent inbreeding. make room for a new male lion. Citing the "pride's natural structure and behavior," the Copenhagen Zoo This time the zoo wasn't planning any public said Tuesday March 25, 2014 that two old lions had dissection. Still, the deaths drew protests on social been euthanized as part of a generational shift.