Copyright and Use of This Thesis This Thesis Must Be Used in Accordance with the Provisions of the Copyright Act 1968

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

![The Charismatic Movement and Lutheran Theology [1972]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/7475/the-charismatic-movement-and-lutheran-theology-1972-67475.webp)

The Charismatic Movement and Lutheran Theology [1972]

THE CHARISMATIC MOVEMENT AND LUTHERAN THEOLOGY Pre/ace One of the significant developments in American church life during the past decade has been the rapid spread of the neo-Pentecostal or charis matic movement within the mainline churches. In the early sixties, experi ences and practices usually associated only with Pentecostal denominations began co appear with increasing frequency also in such churches as the Roman Catholic, Episcopalian, and Lutheran. By the mid-nineteen-sixties, it was apparent that this movement had also spread co some pascors and congregations of The Lutheran Church - Missouri Synod. In cerrain areas of the Synod, tensions and even divisions had arisen over such neo-Pente costal practices as speaking in tongues, miraculous healings, prophecy, and the claimed possession of a special "baptism in the Holy Spirit." At the request of the president of the Synod, the Commission on Theology and Church Relations in 1968 began a study of the charismatic movement with special reference co the baptism in the Holy Spirit. The 1969 synodical convention specifically directed the commission co "make a comprehensive study of the charismatic movement with special emphasis on its exegetical aspects and theological implications." Ie was further suggested that "the Commission on Theology and Church Relations be encouraged co involve in its study brethren who claim to have received the baptism of the Spirit and related gifts." (Resolution 2-23, 1969 Pro ceedings. p. 90) Since that time, the commission has sought in every practical way co acquaint itself with the theology of the charismatic movement. The com mission has proceeded on the supposition that Lutherans involved in the charismatic movement do not share all the views of neo-Pentecostalism in general. -

“I Want to Work and Do Something More Important with My Life,” Says Abed, a Refugee from Syria

WINTER 2018 SOWER “I want to work and do something more important with my life,” says Abed, a refugee from Syria. 1 A lamp to their feet A light to their path For long-time Bible Society the Flying Bible Man, who became chaplain to construction workers supporters Bill and Jocelyn Ross, a great asset. on a dam, Trevor Booth went the Bible really has proved to be “I’d go with Trevor in his plane with him to visit the workers. “He “a lamp to their feet and a light to and catch up with people on the had a good fi lm to show in the their path,” as they have navigated stations. I was fl ying with Trevor workmen’s mess service. On one the roads God has taken them. when the Bible Society made a occasion the sound system wasn’t After studying and marrying fi lm about his work in the East working – but it didn’t matter, in Canberra, Bill and Jocelyn Pilbara. What I remember the because Trevor narrated the fi lm! ministered for a few years in most about the fi lming was the He had shown the fi lm so many Albury, NSW, before moving to constant fl ies in our eyes! ... it was times, he knew the dialogue by the far north of Western Australia a wonderful experience” heart.” in 1970 and beginning a life-long When the Rosses moved to Trevor also assisted with the ministry there. Dampier, a Pilbara port town, Bill They began in the town of again engaged in patrols with Kununurra and the patrol district Trevor at several stations in the of the East Kimberley, with the West Pilbara, and Barrow Island. -

How Covid-19 Changed Community Life in the UK

How Covid-19 changed community CONCLUSION + RECOMMENDATION WEEK 01 + 02: 23RD MARCH OVEWIVEW + KEY INSIGHTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS WEEK 04: 13TH APRIL WEEK 05: 20TH APRIL WEEK 06: 27TH APRIL WEEK 03: 6TH APRIL WEEK 08: 11TH MAY WEEK 09: 18TH MAY WEEK 10: 25TH MAY WEEK 12: 8TH JUNE WEEK 11: 1ST JUNE life in the UK WEEK 07: 4TH MAY A week by week archive of life during a pandemic. Understanding the impact on people and communities. 01/2 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12 The Young Foundation’s mission is to develop better connected and stronger communities across the UK. As an UKRI accredited research organisation, social CONCLUSION + RECOMMENDATION investor and community practitioner, we offer expert WEEK 01 + 02: 23RD MARCH OVERVIEW + KEY INSIGHTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS WEEK 04: 13TH APRIL WEEK 05: 20TH APRIL WEEK 06: 27TH APRIL WEEK 03: 6TH APRIL WEEK 08: 11TH MAY WEEK 09: 18TH MAY WEEK 10: 25TH MAY WEEK 12: 8TH JUNE WEEK 11: 1ST JUNE advice, training and deliver support to: WEEK 07: 4TH MAY Understand Communities Researching in and with communities to increase your understanding of community life today Involve Communities Offering different methods and approaches to involving communities and growing their capacity to own and lead change Innovate with Communities Providing tools and resources to support innovation to tackle the issues people and communities care about For more information visit us at: youngfoundation.org Overview 01/2 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12 Introduction About this document Covid-19 has radically changed the way we go about our day-to-day lives. -

Friday Church News Notes

VOLUME 17, ISSUE 10 WAY OF LIFE MARCH 4, 2016 FRIDAY CHURCH NEWS NOTES THE IMMORALITY CRYSTAL SURROUNDING BIBLE TO LAST HILLSONG MUSIC BILLIONS OF Former Hillsong pastor Pasquale “Pat” Mesiti has pleaded guilty to YEARS assaulting his second wife and is awaiting sentencing (Christian Headlines, Feb. 29, 2016). He was forced to step down in 2002 because of adultery and visiting prostitutes. In an interview with Sight Researchers in the United Kingdom Magazine in May 2006, he said he had a “sexual addiction.” Tat was have developed digital data discs the year he was back in “ministry” afer divorce and remarriage and a that can survive an alleged 13 “restoration” process. He is now known as “Mr. Motivation” and billion years and can withstand promotes a “millionaire mindset” that comes from the charismatic temperatures up to 1,832 F. Te prosperity doctrine. Hillsong, a prominent voice in Contemporary data is encoded by laser onto a glass Worship, began in Australia and has branched out in recent years to disc that can hold 360 terabytes of establish megachurches in many cities, including New York and London. Te following is from a report by Hughie Seaborn titled information, which is equivalent to “Warning: What Do You Know about Hillsong?” which was published the information capacity of 25,500 in response to Hillsong’s World of Worship Conference at the Cairns basic iPhones (“Crystal Bible to last Convention Center September 4-7, 2002. Tis report by a former a billion years,” CNN, Feb. 26, Pentecostal exposes the immorality that is rampant in these circles: 2016). -

A Leader's Guide: Communicating with Teams, Stakeholders, and Communities During COVID-19 Exhibit 1 of 1

Organization Practice A leader’s guide: Communicating with teams, stakeholders, and communities during COVID-19 COVID-19’s speed and scale breed uncertainty and emotional disruption. How organizations communicate about it can create clarity, build resilience, and catalyze positive change. by Ana Mendy, Mary Lass Stewart, and Kate VanAkin © Ewg3D/Getty Images April 2020 Crises come in different intensities. As a “land- communicators, those whose words and actions scape scale” event,1 the coronavirus has created comfort in the present, restore faith in the long great uncertainty, elevated stress and anxiety, and term, and are remembered long after the crisis has prompted tunnel vision, in which people focus only been quelled. on the present rather than toward the future. During such a crisis, when information is unavailable or So we counsel this: pause, take a breath. The good inconsistent, and when people feel unsure about news is that the fundamental tools of effective what they know (or anyone knows), behavioral communication still work. Define and point to science points to an increased human desire for long-term goals, listen to and understand your transparency, guidance, and making sense out of stakeholders, and create openings for dialogue. Be what has happened. proactive. But don’t stop there. In this crisis leaders can draw on a wealth of research, precedent, and At such times, a leader’s words and actions can experience to build organizational resilience through help keep people safe, help them adjust and an extended period of uncertainty, and even turn a cope emotionally, and finally, help them put their crisis into a catalyst for positive change. -

Pentecostal and Charismatic Movements Don Fanning Liberty University, [email protected]

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by Liberty University Digital Commons Liberty University DigitalCommons@Liberty University Trends and Issues in Missions Center for Global Ministries 2009 Pentecostal and Charismatic Movements Don Fanning Liberty University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.liberty.edu/cgm_missions Recommended Citation Fanning, Don, "Pentecostal and Charismatic Movements" (2009). Trends and Issues in Missions. Paper 7. http://digitalcommons.liberty.edu/cgm_missions/7 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Center for Global Ministries at DigitalCommons@Liberty University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Trends and Issues in Missions by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Liberty University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Pentecostal/Charismatic Movements Page 1 Pentecostal Movement The first two hundred years (100-300 AD) The emphasis on the spiritual gifts was evident in the false movements of Gnosticism and in Montanism. The result of this false emphasis caused the Church to react critically against any who would seek to use the gifts. These groups emphasized the gift of prophecy, however, there is no documentation of any speaking in tongues. Montanus said that “after me there would be no more prophecy, but rather the end of the world” (Philip Schaff, History of the Christian Church, Vol II, p. 418). Since his prophecy was not fulfilled, it is obvious that he was a false prophet (Deut . 18:20-22). Because of his stress on new revelations delivered through the medium of unknown utterances or tongues, he said that he was the Comforter, the title of the Holy Spirit (Eusebius, V, XIV). -

Annual Report Two Thousand & Fourteen Hillsong Church, Australia Hillsong Church Annual Report 2 Index

Annual Report Two Thousand & Fourteen Hillsong Church, Australia 2 Annual Report Hillsong Church Index Chairperson’s Report 4 The Church I Now See 5 Lead Pastor’s Report 6 General Manager’s Report 7 History 8 Church Services 10 Programs & Services 12 Children 14 Youth 16 Women 18 Young at Heart 20 Pastoral Care 22 Volunteers 24 Creative Arts 26 Worship 28 Conferences 30 Missions 32 Education 34 Local Community Services 36 Overseas Aid & Development 42 The Hillsong Foundation 46 Two Thousand & Fourteen Two Our Board 48 Financial Reports 51 “I see a church Governance 58 that beckons WELCOME HOME to every man, woman and child that walks through the doors.” – Brian Houston (The Church I Now See) 3 Chairperson’s Report Brian & Bobbie Houston As we reflect on the year past, we can truly thank God for His We have now been holding Hillsong Conference since 1986 unwavering goodness and love for humanity. God specialises with the mission: Championing the cause of local churches in lifting people out of tragedy and pain, rebuilding hope and everywhere. With over 22,000 attendees and 19 Christian restoring us to a friendship with Him. denominations represented we celebrate the diversity of the expressions of our faith and gather around the common We as a church are privileged to play our role in seeing lives understanding that a healthy local church can make a positive impacted through the Gospel of Jesus Christ. At Hillsong impact in its community. Church, hundreds of people make a decision to follow Christ each week, a foundational step on a journey of personal It is with this understanding we are enthusiastic about freedom and understanding. -

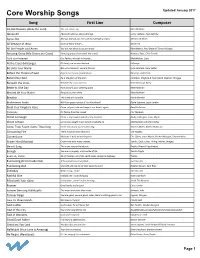

Core Worship Songs Updated January 2017 Song First Line Composer

Core Worship Songs Updated January 2017 Song First Line Composer 10,000 Reasons (Bless the Lord) The sun comes up, Matt Redman Above All Above all nations, above all kings Lenny LeBlanc, Paul Baloche Agnus Dei Alleluia, alleluia, for the Lord God Almighty reigns Michael W Smith All because of Jesus Giver of every breath… Steve Fee All the People said Amen You are not alone if you are lonely Matt Maher, Paul Moak & Trevor Morgan Amazing Grace (My Chains are Gone) Amazing grace, how sweet the sound Newton, Rees, Chris Tomlin As it is in heaven Our Father, who art in heaven… Matt Maher, Cash At the Cross (Hillsongs) Oh Lord, you've searched me Hillsongs Be Unto Your Name We are a moment, you are forever Lynn DeShazo, Gary Sadler Before the Throne of God Before the throne of God above Bancroft, Vicki Cook Behold Our God He is the glory of the stars Jonathan, Meghan & Ryan Baird, Stephen Altrogge Beneath the Cross Beneath the cross of Jesus Keith & Kristyn Getty Better Is One Day How lovely is your dwelling place Matt Redman Blessed Be Your Name Blessed be your name Matt Redman Breathe This is the air I breathe Marie Barnett Brokenness Aside Will Your grace run out if I let You down? David Leonard, Leslie Jordan Build Your Kingdom Here Come set your rule and reign in our hearts again Rend Collective Cannons It's falling from the clouds Phil Wyckam Christ is Enough Christ is my reward and all of my devotion Reuben Morgan, Jonas Myrin Christ is Risen Let no one caught in sin remain insidethe lie Matt Maher and Mia Fieldes Come Thou Fount, Come -

February 2004

VOLUME 31/1 FEBRUARY 2004 “Do you not give the horse his strength or clothe his neck with a flowing mane?” Job 39:19 faith in focus Volume 31/1, February 2004 CONTENTS Editorial Whose party are you going to? Uncovering a very present danger 3 It was some years ago that a minister was overhearing several colleagues at a minister’s conference speaking about several high-powered revival meetings Not satisfied with Jesus? When faith is not alone 7 they had experienced. They spoke in glowing terms of how warmly they felt and how much everyone there shared a wonderful spiritual unity. Sons of encouragement 8 This minister shared with them his own experience of a meeting he had come World News 9 from the night before he flew over. He detailed the feelings he had when over Breakthrough 40,000 sang the same songs, held hands, and came away with a truly The lesson in life 11 unforgetable event. Missions in focus His colleagues now were completely captivated by his story. This was something Growing the church in Karamoja extraordinary. And to hear all this from this man who otherwise you would think Prayer points RCNZ food aid to Malawi 12 was the last to be open to such a move of the Spirit! They had to ask him who was the cause for this incredible time. Which special person’s meeting was it? Surfing the Net The upside & downside of the Internet 15 “Oh,” the minister replied, “it was a Paul McCartney concert.” Naturally, those ministers felt somewhat taken in. -

Pentecostal Pastorpreneurs and the Global Circulation of Authoritative Aesthetic Styles

Culture and Religion An Interdisciplinary Journal ISSN: 1475-5610 (Print) 1475-5629 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/rcar20 Pentecostal pastorpreneurs and the global circulation of authoritative aesthetic styles Miranda Klaver To cite this article: Miranda Klaver (2015) Pentecostal pastorpreneurs and the global circulation of authoritative aesthetic styles, Culture and Religion, 16:2, 146-159, DOI: 10.1080/14755610.2015.1058527 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/14755610.2015.1058527 Published online: 14 Jul 2015. Submit your article to this journal Article views: 335 View related articles View Crossmark data Citing articles: 1 View citing articles Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=rcar20 Download by: [Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam] Date: 30 October 2017, At: 06:47 Culture and Religion, 2015 Vol. 16, No. 2, 146–159, http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/14755610.2015.1058527 Pentecostal pastorpreneurs and the global circulation of authoritative aesthetic styles Miranda Klaver* Faculty of Theology and Religious Studies, VU University Amsterdam Amsterdam, The Netherlands This article argues that the rise of ‘pastorpreneurs’ in global neo- Pentecostalism calls for an aesthetic perspective on religious authority and leadership in the context of new media. Different from mainline churches, religious leadership in neo-Pentecostal (In many parts of the world, neo-Pentecostal or new Pentecostal churches have emerged since the 1980s. They are usually independent churches, organized in loose national or transnational networks, Anderson 2004) churches is not legitimised by denominational traditions and the ordination of clergy but by ‘pastorpre- neurs’, (Twitchell uses the term pastorpreneurs to describe megachurch pastors who by using marketing techniques and other entrepreneurial business skills create stand-alone religious communities that challenge top- down denominationalism (2007:3). -

AN AUSTRALIAN PERSPECTIVE Kameel Majdali 1

[AJPS 6:2 (2003), pp. 265-281] CHRISTIAN LEADERSHIP IN THE TWENTY-FIRST CENTURY: AN AUSTRALIAN PERSPECTIVE Kameel Majdali 1. Introduction When one hears the word “Australia,” usually one of several images spring to mind: kangaroos and koalas, fun-loving sunbathers lying on the beach, a bunch of mates huddled in the local pub having their beer for the night, a convict colony and/or last bastion of the British Empire. What may not be so readily apparent is that this fully independent, sparsely populated island-continent nation is one of the most multicultural havens in the world. It forms a juxtaposition for East Asia, the Pacific Isles and, yes, Antarctica, which is a mere five thousand kilometers away. Though clearly located in the South Pacific, Australia is firmly a member of “the West,” with all the attendant benefits and plagues of any other western nation. With thirty thousand kilometers of coastline, a sun-baked interior, an inhospitable northern coast but fertile underbelly in the southeast, this Australia is also known as an enclave of prosperity, liberal democracy, a relaxed lifestyle and high standard of living. Indeed this relatively young nation has excelled in many areas. Little wonder it is one of the few favored havens for migrants from around the world, not to mention millions of tourists who are willing to brave the long flights (fourteen hours non-stop from Los Angeles to Melbourne, or nineteen hours from London) to experience this attractive and prosperous land. While Australia’s background as a penal colony is very well known, what may not be so clear is that there has been a conspicuous, even dominant, Christian presence in this land, beginning with the First Fleet of 1788. -

Engaging the Young Volunteer

Australian HThe Annual ReviewOSPITALLER of the2017 Australian Association of the Sovereign Order of Malta ENGAGING THE YOUNG VOLUNTEER KOREA Korean Delegation’s first report PILGRIMAGE Walking in the footsteps of St Paul COATS CAMPAIGN The Order’s 900 year old mission in action Lieutenant of the Grand Master Frà Giacomo Dalla Torre del Tempio di Sanguinetto was elected on 29 April 2017 by the Council Complete of State for one year. Australian WELCOME HOSPITALLER2017 elcome to the Australian Hospitaller magazine, the Annual Australian Review of the Australian Association of the Sovereign Order of Malta, for the year 2017. HThe Annual ReviewOSPITALLER of the2017 Australian Association of the Sovereign Order of Malta WThis edition takes a look at the challenge facing our Order both in Australia and the Order’s national associations around the world; that of engaging and recruiting young volunteers to the Order of Malta’s ENGAGING mission to the needs of the poor, the sick, the elderly, the handicapped, THE YOUNG the outcast and the refugee. Our article on Homelessness highlights the VOLUNTEER plight of the growing number of rough sleepers in Australia. In some of our cities, walking by these poor souls without your heart going out to them can be extremely hard and the many unanswered stories about their current situation and their plight are just as difficult to comprehend. KOREA Korean Delegation’s first report The Australian Association mourned the loss of a number of PILGRIMAGE members in 2017 and in this edition we have selected three obituaries: Walking in the footsteps of St Paul COATS CAMPAIGN the Association’s only Knight of Justice Frà Richard Divall AO OBE The Order’s 900 year old mission in action CMM; celebrated portrait painter Confrere Paul Fitzgerald AM KMG; and former Australian Association Master of Ceremonies Confrere Thomas (Tom) Hazell AO KHS KMG CMM.