Mid and East Antrim LBAP

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Monitoring Northern Ireland

Northern Ireland RRegionalegional ReportReport ofof thethe NationalNational MonitoringMonitoring ProgrammeProgramme Marine Pollution Monitoring Management Group NOVATIO IN N INDUSTRIAL RESEARCH & RECHNOLOGY UNIT IN T SS O SU C CE DEPARTMENT OF AGRICULTURE FOR NORTHERN IRELAND Northern Ireland Regional Report of the National Monitoring Programme Marine Pollution Monitoring Management Group This report has been produced by: J.P. Breen, IRTU E.L. Donaldson, IRTU M. Service, DANI C. Vincent, EHS Contents 1 Introduction 1 2 Methods 4 2.1. Sample Plan 4 2.1.1. Seawater Analysis 4 2.1.2. Sediment Analysis 4 2.1.3. Biota Analysis 4 2.1.4. Shellfish 7 2.1.5. Fish 7 2.2. Sample Design 7 2.3. Biological Effects 8 2.3.1. Benthic Macrofauna 8 2.3.2. Oyster Embryo 8 2.3.3. Fish Disease Studies 8 2.3.4. Dogwhelk Imposex Studies 9 2.3.5. The Mixed Function Oxidase Test (EROD) 9 3 Quality Control 10 3.1. Chemical Data 10 3.1.1. Seawater Analysis 10 3.1.2. Sediment Analysis 10 3.1.3. Biota Analysis 10 3.2. Biological Data 10 4 Benthos 12 4.1. Number of Individuals 12 4.2. Number of Species 12 4.3. Biomass 12 4.4. Univariate Analysis 12 4.4.1. Species Richness 15 4.4.2. Pielou’s Evenness 15 4.4.3. Simpson’s Index 15 4.4.4. Shannon-Weiner 15 4.5. Multivariate Analysis 15 4.5.1. Multidimensional Scaling 15 4.5.2. SIMPER Analysis 18 4.5.3. K-Dominance Plot 19 5 Biological Effects 20 5.1. -

APRIL 2020 I Was Hungry and You Gave Me Something to Eat Matthew 25:35

APRIL 2020 I was hungry and you gave me something to eat Matthew 25:35 Barnabas stands alongside our Christian brothers and sisters around the world where they suffer discrimination and persecution. By providing aid through our Christian partners on the ground, we are able to maintain our overheads at less than 12% of our income. Please help us to help those who desperately need relief from their suffering. Barnabas Fund Donate online at: is a company Office 113, Russell Business Centre, registered in England 40-42 Lisburn Road, Belfast BT9 6AA www.barnabasaid.org/herald Number 04029536. Registered Charity [email protected] call: 07875 539003 Number 1092935 CONTENTS | APRIL 2020 FEATURES 12 Shaping young leaders The PCI Intern Scheme 16 Clubbing together A story from Bray Presbyterian 18 He is risen An Easter reflection 20 A steep learning curve A story from PCI’s Leaders in Training scheme 22 A shocking home truth New resource on tackling homelessness 34 Strengthening your pastoral core Advice for elders on Bible use 36 Equipping young people as everyday disciples A shocking home truth p22 Prioritising discipleship for young people 38 A San Francisco story Interview with a Presbyterian minister in California 40 Debating the persecution of Christians Report on House of Commons discussion REGULARS A San Francisco story p38 Debating the persecution of Christians p40 4 Letters 6 General news CONTRIBUTORS 8 In this month… Suzanne Hamilton is Tom Finnegan is the Senior Communications Training Development 9 My story Assistant for the Herald. Officer for PCI. In this role 11 Talking points She attends Ballyholme Tom develops and delivers Presbyterian in Bangor, training and resources for 14 Life lessons is married to Steven and congregational life and 15 Andrew Conway mum to twin boys. -

Dunluce Guide House Stamped Addressed A5 Enveloped Other Organizations Per Night £8.00

Booking from checklist: Charges Completed booking form Guide & Scout Association members Per night £7.00 Dunluce Guide House Stamped addressed A5 enveloped Other Organizations www.dunluceguidehouse.org.uk Per night £8.00 £40.00 Deposit (non-refundable) Service Charge Per night £25.00 Please make cheques made payable to: (Prices subject to change) Dunluce Guide House Optional Cleaning £30.00 Camping Duke of Edinburgh’s Award groups only Per night £2.00 Send to: Cleaning Dun- luce Guide House should be thoroughly cleaned Dunluce Guide House is situated in an area of Mrs. Jayne Johnston before leaving. There is an optional choice of pay- outstanding natural beauty on Northern Ireland’s The Booking Secretary ing for the house to be cleaned at the end of your scenic North Antrim coast, close to historic Dunluce 159 Ballygowan Road stay. Please indicated your choice when booking. Castle and the world famous Giant’s Causeway. Hillsborough All breakages must be reported before leaving. BT26 6EG The house offers self-catered, centrally heated www.dunluceguidehouse.org.uk accommodation for up to 28 people. Outside Our website contains lots more information about catering available. Groups have exclusive use of the Dunluce Guide House including detailed infor- House and grounds. mation on local activities, places to visit, maps and directions Contact the Booking Secretary: Bookings& Queries Mrs Jayne Johnston Mrs. Jayne Johnston 159 Ballygowan Road 159 Ballygowan Road, Hillsborough, BT26 6EG Hillsborough Tel. 028 9269 9747 BT26 6EG Tel. 028 9269 9747 Dunluce Guide House Dunluce Guide House Local activities Booking Form 71-73 Ballytober Road Canoeing Name or Unit or Group Bushmills Surfing / Bodyboarding BT57 8UU Banana-Boating Archery Horse Riding 10-pin bowling Swimming Details of Leader in charge of party: Full activity details available upon booking. -

Minutes of Carrickfergus Children and Young People's

MINUTES OF CARRICKFERGUS CHILDREN AND YOUNG PEOPLE’S LOCALITY PLANNING GROUP MEETING FRIDAY 8TH SEPTEMBER 2017 AT 10.00AM IN CARRICKFERGUS TOWN HALL BUILDINGS Attending: Roy Beggs MLA (Chairperson) Helen Christie Autism NI Ivor Mitchell Carrick YMCA Janice Cherry CCF Karen Dunlop Women’s Aid Liz Brown NICMA Margaret Armstrong Sure Start Pamela McClelland SACN Rebecca Sylvest Action for Children Sandra Anderson CYPSP Selena Ramsey CYPSP Apologies: Amy Holt Northern HSC Trust David McAllister Mid & East Antrim Borough Council Denise McVeigh Mid & East Antrim Borough Council Gabrielle Rawashdeh PHA Gemma Lutton CYPSP Hedley Webb Carrickfergus College Lynn McKenzie Relationship Resource Centre Phyllis Lewis EA NI Sharon Crawford Northern HSC Trust WELCOME AND INTRODUCTIONS Roy welcomed everyone to the meeting today and invited a round of introductions. 1 MINUTES OF PREVIOUS MEETING The minutes were agreed as being a true and accurate recording of the previous workshop held on Friday 5th May 2017. MATTERS ARISING No matters arising. PRESENTATION- KAREN DUNLOP, VOICES COORDINATOR CARRICKFERGUS Karen delivered a presentation on the Voices Project in Carrickfergus. This is a Big Lottery Funded 3 Year Project with a target age group of 14+. The project focuses on healthy relationships, consent and violence. Karen noted there will be a Voices Coordinator in every area: Antrim, Ballymena, Carrickfergus, Larne and Newtownabbey. Karen aims to set up a group of young women in Carrickfergus. This will be open for everyone to participate in. Information was also provided on ‘Safe Place’. Women’s Aid are currently seeking organisations to sign up to the charter. Teachers can also avail of training to become a Safe School. -

Health Falls Ward HB26/33/004 St, Comgall’S Primary School, Divis Street, Belfast, Co

THE BELFAST GAZETTE FRIDAY 25 JANUARY 2002 65 The Department of the Environment hereby gives notice that on 19th The Department of the Environment hereby gives notice that on 19th December 2001, it prepared a list of buildings of special architectural December 2001, it prepared a list of buildings of special architectural or historic interest under Article 42 of the Planning (Northern Ireland) or historic interest under Article 42 of the Planning (Northern Ireland) Order 1991. Order 1991. District of Larne District of Larne Ballycarry Ward Ballycarry Ward HB06/05/013F HB06/05/049 Garden Turret at Red Hall, Ballycarry, Larne, Co. Antrim. 54 Main Street, Ballycarry, Carrickfergus, Co. Antrim, BT38 9HH. The Department of the Environment hereby gives notice that on 19th The Department of the Environment hereby gives notice that on 19th December 2001, it prepared a list of buildings of special architectural December 2001, it prepared a list of buildings of special architectural or historic interest under Article 42 of the Planning (Northern Ireland) or historic interest under Article 42 of the Planning (Northern Ireland) Order 1991. Order 1991. District of Larne District of Larne Ballycarry Ward Ballycarry Ward HB06/05/013E HB06/05/036 Garden Piers at Red Hall, Ballycarry, Larne, Co. Antrim. Lime kilns at 9 Ballywillin Road, Glenoe, Larne, Co. Antrim. The Department of the Environment hereby gives notice that on 19th Historic Monuments December 2001, it prepared a list of buildings of special architectural or historic interest under Article 42 of the Planning (Northern Ireland) The Department of the Environment hereby gives notice that on the Order 1991. -

Copy of Nipx List 16 Nov 07

Andersonstown 57 Glen Road Belfast BT11 8BB Antrim 27-28 Castle Centre Antrim CO ANTRIM BT41 4AR Ards Centre Ards Shopping Centre Circular Road Newtownards County Down N Ireland BT23 4EU Armagh 31 Upper English St. Armagh BT61 7BA BALLEYHOLME SPSO 99 Groomsport Road Bangor County Down BT20 5NG Ballyhackamore 342 Upper Newtonards Road Belfast BT4 3EX Ballymena 51-63 Wellington Street Ballymena County Antrim BT43 6JP Ballymoney 11 Linenhall Street Ballymoney County Antrim BT53 6RQ Banbridge 26 Newry Street Banbridge BT32 3HB Bangor 143 Main Street Bangor County Down BT20 4AQ Bedford Street Bedford House 16-22 Bedford Street Belfast BT2 7FD Belfast 25 Castle Place Belfast Northern Ireland BT1 1BB BLACKSTAFF SPSO Unit 1- The Blackstaff Stop 520 Springfield Road Belfast County Antrim BT12 7AE Brackenvale Saintfield Road Belfast BT8 8EU Brownstown Road 11 Brownstown Road Portadown Craigavon BT62 4EB Carrickfergus CO-OP Superstore Belfast Road Carrickfergus County Antrim BT38 8PH CHERRYVALLEY 15 Kings Square Belfast BT5 7EA Coalisland 28A Dungannon Road Coalisland Dungannon BT71 4HP Coleraine 16-18 New Row Coleraine County Derry BT52 1RX Cookstown 49 James Street Cookstown County Tyrone BT80 8XH Downpatrick 65 Lower Market Street Downpatrick County Down BT30 6LZ DROMORE 37 Main Street Dromore Co. Tyrone BT78 3AE Drumhoe 73 Glenshane Raod Derry BT47 3SF Duncairn St 238-240 Antrim road Belfast BT15 2AR DUNGANNON 11 Market Square Dungannon BT70 1AB Dungiven 144 Main Street Dungiven Derry BT47 4LG DUNMURRY 148 Kingsway Dunmurray Belfast N IRELAND -

LISBURN & CASTLEREAGH CITY COUNCIL Island Civic Centre The

LISBURN & CASTLEREAGH CITY COUNCIL Island Civic Centre The Island Lisburn BT27 4RL 26 May, 2016 TO: The Right Worshipful the Mayor, Aldermen & Councillors of Lisburn & Castlereagh City Council The monthly meeting of Lisburn & Castlereagh City Council will be held in the Council Chamber, Island Civic Centre, The Island, Lisburn, BT27 4RL, on Tuesday, 31 May 2016 at 7.00 pm for the transaction of the business on the undernoted Agenda. You are requested to attend. Food will be available in Lighters Restaurant from 5.30 pm. DR THERESA DONALDSON Chief Executive Lisburn & Castlereagh City Council AGENDA 1 BUSINESS OF THE RIGHT WORSHIPFUL THE MAYOR 2 APOLOGIES 3 DECLARATION OF MEMBERS’ INTERESTS; (i) Conflict of interest on any matter before the meeting (Members to confirm the specific item) (ii) Pecuniary and non-pecuniary interest (Member to complete the Disclosure of Interest form) 4 COUNCIL MINUTES - Meeting of Council held on 26 April, 2016 5 MATTERS ARISING 6 DEPUTATIONS (None) 7 BUSINESS REQUIRED BY STATUTE (i) Signing of Legal Documents Northern Ireland Housing Executive of 2 Adelaide Street, Belfast to Lisburn and Castlereagh City Council – Memorandum of Sale in respect of purchase of land at Rushmore Avenue/Drive, Lisburn Lisburn and Castlereagh City Council and Mullinsallagh Limited of 28 Townhill Road, Portglenone, Ballymena, County Antrim, BT44 8AD – Contract – West Lisburn Youth Resource Centre and Laganview Enterprise Centre SIF Projects Education Authority of Forestview, Purdy’s Lane, Belfast, BT8 7AR and Lisburn and Castlereagh -

Barge 1 Lagan Waterway and History

LAGAN WATERWAY HISTORY Navigable waterways Prior to the advent of canals and railways in the 1700s and 1800s, packhorses and horses and carts or packhorse were the main means of moving stuff. Although Ireland has had a good road network since the 1600s, such roads were poorly surfaced and not always well maintained. The loads transported were thus limited by the hauling power of the horses and condition of the roads. Bulky, low-value goods such as coal, building materials and grain were particularly expensive to transport. Railways solved this problem, but only after the development of reliable steam locomotives in the mid-1800s. Before then, rivers were the cheapest way of moving large heavy loads where speed was not essential. Except for their tidal sections however, most rivers were not navigable for any great distance and the size of boats, and thus of the loads carried, was invariably limited by obstructions such as shallows, rapids and weirs. Navigations and canals Navigable waterways are of two types – navigations and canals. Navigations are existing natural watercourses whose navigability has been improved, whereas canals are entirely artificial channels excavated by hand and/or machine. The pros and cons of each type of waterway are as follows: For Against Navigations No major civil engineering works Prone to strong currents in winter and required so relatively cheap. lack of water in summer, both of which may make navigation temporarily impossible. [This was certainly the case on the Lagan] Summer water shortages are potentially exacerbated by demands of mill owners with prior rights to abstract water from the river. -

The Belfast Gazette, July 4, 1930. 837

THE BELFAST GAZETTE, JULY 4, 1930. 837 STATUTORY NOTICE BY THE MINISTRY i i No. Memorialist Amount Lands to be . Barony County. OP FINANCE, NORTHERN IRELAND. Charged. 84 William £120 Canow- 1 Upper Armagh Application has been made by the under- King mannon I Oiior mentioned for a loan under the Landed Dissents or objections, with reasons therefor, Property Improvement (Ireland) Acts (10 & 11 must be transmitted to the Ministry of Finance, Vic., Chap. 32, etc.), as made applicable to on or before the 26th July, 1930. Northern Ireland by virtue of the Government G. C. DUGGAN, of Ireland Act, 1920, and the Statutory Assistant Secretary. Orders made thereunder: — Ministry of Finance, Belfast, 26th June, 1930. PROVISIONAL LIST No. 1731. LAND PURCHASE COMMISSION, NORTHERN IRELAND. NORTHERN IRELAND LAND ACT, 1925. ESTATE OF SOLOMON HENRY DARCUS. County of Antrim. Record No. N.I. 1515. WHEREAS the above-mentioned Solomon Henry Darcus claims to be the Owner of land in the Townland of B rowndod, Barony of Lower Belfast, and of land in the Townland of Ballymena, Barony of Lower Antrim, both in the County of Antrim: Now in pursuance of the provisions of Section 17, Sub-section 2, of the above Act the Land Purchase Commission, Northern Ireland, hereby publish the following Provisional List of all land in the said Townlands of which the said Solomon Henry Darcus claims to be the Owner, which will become vested in the said Commission by virtue of Part II of the Northern Ireland Land Act, 1925, on the Appointed Day to be hereafter fixed. -

Sustainability Appraisal Scoping Report Local Development Plan 2030 - Draft Plan Strategy

Sustainability Appraisal Scoping Report Local Development Plan 2030 - Draft Plan Strategy Have your say Mid and East Antrim Borough Council is consulting on the Mid and East Antrim Local Development Plan - Draft Plan Strategy 2030. Formal Consultation The draft Plan Strategy will be open for formal public consultation for a period of eight weeks, commencing on 16 October 2019 and closing at 5pm on 11 December 2019. Please note that representations received after the closing date on 11 December will not be considered. The draft Plan Strategy is published along with a range of assessments which are also open for public consultation over this period. These include a Sustainability Appraisal (incorporating a Strategic Environmental Assessment), a draft Habitats Regulations Assessment, a draft Equality (Section 75) Screening Report and a Rural Needs Impact Assessment. We welcome comments on the proposals and policies within our draft Plan Strategy from everyone with an interest in Mid and East Antrim and its continuing development over the Plan period to 2030. This includes individuals and families who live or work in our Borough. It is also important that we hear from a wide spectrum of stakeholder groups who have particular interests in Mid and East Antrim. Accordingly, while acknowledging that the list below is not exhaustive, we welcome the engagement of the following groups: . Voluntary groups . Business groups . Residents groups . Developers/landowners . Community forums and groups . Professional bodies . Environmental groups . Academic institutions Availability of the Draft Plan Strategy A copy of the draft Plan Strategy and all supporting documentation, including the Sustainability Appraisal Report, is available on the Mid and East Antrim Borough Council website: www.midandeastantrim.gov.uk/LDP The draft Plan Strategy and supporting documentation is also available in hard copy or to view during office hours, 9.30am - 4.30pm at the following Council offices: . -

The Belfast Gazette, March 1, 1929. 237

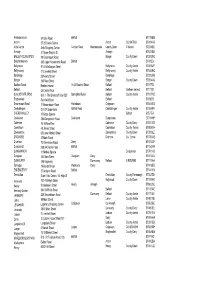

THE BELFAST GAZETTE, MARCH 1, 1929. 237 Reference 1 • Standard 1 Standard 1 ; No. on ' Purchase i Price i Map filed i Annuity ' if Land Name of Tenant. Postal Address. Barony. Townland. la Land i Area. 1 Bent. if Land becomes teg.. Purchase becomes , verted. JSo. Oommia- • vested. ; j i sion. j i i i i. R. P.! £ s. d. £ s. d.l £ s. d. Holdings subject to Judicial Rents fixed alter the 15th August, 1911—(continued). 242 Hannah Lena Shaw Duneany, Kflconway Duneany 36r 36A 34 3 6 16 3 0.14 5 6300 10 6 (wife of Samuel Glarryford, Shaw) Co. Antrim. 243 Robert Stevenson Kells, Lower Antrim Kells 4, 4A 13 1 37 7 0 0 6 3 10 130 7 0 Ballymena, Co. Antrim. ' 244 Margaret Strahan do. do. do. 8, 8A 9 2 12 8 15 0; 7 14 8162 16 2 /spinster) i 245 William George ' do. do. do. 12 18 2 18 12 0 0 9 IS 2208 11 11 McCullough 246 Hugh Jack Springfield, do. do. 17, 17A 14 1 18 9 13 0, 8 10 8179 13 0 Kells, 17B Ballymena, Co. Antrim. 249 Robert Cupples Kells, ! do. do. 21 713 3 7 0! 2 19 2 62 5 7 Ballymena, i Co. Antrim. 261 Robert Barkley Kildrum, do. Kildrum 11, 11A 11 2 6 6 17 0 6 1 2127 10 11 Kells, Ballymena, Co. Antrim. 263 John Allen. do. do. do. 13 6 1 22 3 15 01 3 6 4 69 16 (i 264 James McAlonan Killycowan, Kileonway KJllycowan 4 52 0 38 23 10 OrL'O 13 0 434 14 9 Glarryford, t Co. -

Patriots, Pioneers and Presidents Trail to Discover His Family to America in 1819, Settling in Cincinnati

25 PLACES TO VISIT TO PLACES 25 MAP TRAIL POCKET including James Logan plaque, High Street, Lurgan FROM ULSTER ULSTER-SCOTS AND THE DECLARATION THE WAR OF 1 TO AMERICA 2 COLONIAL AMERICA 3 OF INDEPENDENCE 4 INDEPENDENCE ULSTER-SCOTS, The Ulster-Scots have always been a transatlantic people. Our first attempted Ulster-Scots played key roles in the settlement, The Ulster-Scots/Scotch-Irish contribution to the Patriot cause in the events The Ulster-Scots/Scotch-Irish played important roles in the military aspects of emigration was in 1636 when Eagle Wing sailed from Groomsport for New England administration and defence of Colonial America. leading up to and including the American War of Independence was immense. the War of Independence. General Richard Montgomery was the descendant of SCOTCH-IRISH but was forced back by bad weather. It was 1718 when over 100 families from the Probably born in County Donegal, Rev. Charles Cummings (1732–1812), a a Scottish cleric who moved to County Donegal in the 1600s. At a later stage the AND SCOTS-IRISH Bann and Foyle river valleys successfully reached New England in what can be James Logan (1674-1751) of Lurgan, County Armagh, worked closely with the Penn family in the Presbyterian minister in south-western Virginia, is believed to have drafted the family acquired an estate at Convoy in this county. Montgomery fought for the regarded as the first organised migration to bring families to the New World. development of Pennsylvania, encouraging many Ulster families, whom he believed well suited to frontier Fincastle Resolutions of January 1775, which have been described as the first Revolutionaries and was killed at the Battle of Quebec in 1775.