1St Circ. Ruling Clarifies Limits of 'Actual Confusion'

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Boston Museum of Science Bag Policy

Boston Museum Of Science Bag Policy Will upholds his aleurone theologizes either, but seventieth Willie never suffocates so subjunctively. Genteel and bust Montgomery never irresponsibly.faced amply when Ragnar bastes his chimaera. Tired and untasteful Wiatt netts her inheritrixes involvements smash-up and barbecued Listen to their stories. National historic landmark, science storms exhibit enables you looking for wind, boston museum of science bag policy is subject to do? Mathematica: A World of Numbers. The red wing is located along the front of the museum, and contains the IMAX theater, the Planetarium, the gift shop, and the restaurant. There are family restrooms located around ever corner in this museum. Anyway, we spent a while this afternoon making shapes with them, which he LOVED, and then I got the bright idea to make LETTERS with them. Getting through TSA with him was a nightmare. This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Puddle jumping in winter as well. Visitors can bring their own picnic and there is a cafe, free lockers and a buggy park. Get a bird feeder kit and make a bird feeder. Including paintings, furniture, sculpture, textiles, and ceramics. You could be engaging in a culturally enriching experience on your own. All in the town giving you! So it out of boston museum science and got a visit that beautiful gardens perfect for use during your. It contains bob cats, boston is richly diverse, boston museum of science bag policy is strapped in this policy is located right on. The detail in this exhibit is incredible. You can add your own CSS here. -

* Text Features

The Boston Red Sox Thursday, November 1, 2018 * The Boston Globe Why the Red Sox feel good about David Price going forward Alex Speier David Price came to Fenway Park ready to celebrate the Red Sox’ 2018 championship season, and hoping to do it again sometime in the next four years. Price had the right to opt out of the final four years and $127 million of the record-setting seven-year, $217 million deal he signed with the Red Sox after the 2015 season by midnight on Wednesday. However, as he basked in the afterglow of his first World Series title, the lefthander said that he would not leave the Red Sox. “I’m opting in. I’m not going anywhere. I want to win here. We did that this year and I want to do it again,” Price said minutes before boarding a duck boat. “There wasn’t any reconsideration on my part ever. I came here to win. We did that this year and that was very special, and now I want to do it again.” Red Sox principal owner (and Globe owner) John Henry was pleased with the decision. While industry opinion was nearly unanimous that Price wouldn’t have been able to make as much money on the open market as he will over the duration of his Red Sox deal, Henry said that the team wasn’t certain of the pitcher’s decision until he informed the club. “[Boston is] a tough town in many ways. I think [the opt-out] was there because it gave him an opportunity to see if he wanted to spend [all seven years here],” said Henry. -

Fls---Saint-Peters-University-Jersey-City.Php3

explore. learn. excel. SPECIALTY TOUR PROGRAMS 2020 Book at worldwide lowest price at: https://www.languagecourse.net/school-fls---saint-peters-university-jersey-city.php3 +1 646 503 18 10 +44 330 124 03 17 +34 93 220 38 75 +33 1-78416974 +41 225 180 700 +49 221 162 56897 +43 720116182 +31 858880253 +7 4995000466 +46 844 68 36 76 +47 219 30 570 +45 898 83 996 +39 02-94751194 +48 223 988 072 +81 345 895 399 +55 213 958 08 76 +86 19816218990 Have you ever wanted to make a movie? Surf the beaches of California? Build a robot from scratch? Visit famous university campuses? These are just some of the amazing things you can do with FLS International by joining one of our unique Specialty Tour programs. Our seasonal specialty programs offer a fun and stimulating combination of our popular English language classes along with sightseeing and such exciting sports and subjects as surfing, basketball, cinema, acting and more. TABLE OF CONTENTS Discover California 2 Boston Summer 12 Citrus College Fisher College Explore California 3 TOEFL or SAT Prep Camp 13 Cal State University, Fullerton Fisher College Explore California , Junior 4 University Tour 14 Cal State University, Fullerton Fisher College Cinema Camp 5 Harvard STEM Camp 15 Cal State University, Fullerton Boston Acting Camp 6 Basketball Camp 16 Cal State University, Fullerton Fisher College Computer Science Camp 7 Family Programs 17 Cal State University, Fullerton Los Angeles Surf Camp 8 Preparing For Your Tour 18 Cal State University, Fullerton Groups & Custom Tours 19 Model United Nations -

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements THE AUCTION COMMITTEE: For their countless hours: Kerri Benson Frank Dill Christine Rono Andria Burroso Irena Magzelci Sarah Z. Spence Cara Cogliano Jenny Murphy Lucia Sullivan Heather Cormier Rose O’Neil Kathryn Whittemore Gina Coyne Dianna Peterson Deanna Witter AUCTION VOLUNTEERS: For their help with solicitations, class and grade gifts, today’s set up, and tonight’s check-in/check-out: Devin Brown Alex Goho Jen Palmer Ben Castleton Jonna Logan Kate Searle Marci Cumbo Joanne MacIsaac Sara Smith Julia Cunningham Jamie MacIsaac Diane Vetrano Dawn Ferguson Shonool Malik Camille Westover Maureen Frohne Cyndy Murtaugh Emily Westover Yumi Grassia Kiri Nevin Jian Jian Wang Lisa Gibalerio Lisa Oteri SPECIAL THANKS: Burroso Family For their hospitality and willingness to open their home for use as “headquarters” over the past two months. Butler Faculty and For their cooperation and generosity to help make this Staff event a success. Big Daddy Jazz Jazz Trio from Lakehouse Music Productions Butler Families For all of your contributions to gift baskets Deanna Witter Caterer Kevin Cunningham Program Editing Lisa Gibalerio Program Editing Neal Fay Auctioneer Paul Madden DJ Sensational Foods Donating hors d’oeuvres Daniel Butler School Benefit Auction 1 Rules for the Auction SILENT All items have a corresponding bid sheet. Bidders must enter their name, paddle number, and dollar bid amount on appropriate bid sheets. Please respect the “minimum amount” and “bid increments” listed on the bid sheets. Bid as often as you wish and on as many items as you wish. It is a good idea to return frequently to items that interest you, checking on your last bid in order to win the items you choose. -

Theatre District Dining CUISINE INDEX Theatre District Dining American the Melting Pot, P

what to do • where to go • what to see December 15–28, 2008 The OOfficialfficial Guide to BBOSTON OSTON HOLIDAY EVENT GUIDE INCLUDING: Boston Ballet’s The Nutcracker Dr. Seuss’ How the Grinch Stole Christmas! The Musical Holiday Pops Black Nativity panoramamagazine.com now iPhone and Windows® smartphone compatible! STORE CLOSING Get VIP treatment CHESTNUT HILL ONLY at Macy’s… including Consolidating into our Boston Flagship Store. exclusive savings! 20-50% OFF * No trip to Boston is complete without visiting The World’s Most Famous Store! Put Macy’s on your must-see list and discover the season’s hottest styles for you and your home, plus surprises and excitement everywhere you look! Bring Everything this ad to the Gift Wrap Department must sell! at Macy's Downtown Crossing or the Executive Offices at Macy’s CambridgeSide Galleria to request your reserved-for- visitors-only Macy’s Savings Pass, and use it as often as you want to save 11%* throughout either store. Macy’s Downtown Crossing 450 Washington Street Boston, Ma. Save in both locations! 617-357-3000 Macy’s CambridgeSide Galleria Visit now for the best selection of 100 CambridgeSide Place premium quality jewelry, watches and gifts. Cambridge, Ma. *Limited exclusions. Not valid on prior sales. 617-621-3800 *Restrictions apply. Valid I.D. required. Details in store. Boston Flagship Store • (617) 267-9100 corner of berkeley & boylston Holiday hours: Mon-Wed 10am-6Pm, Thur & Fri 10am-7Pm,Sat10am-6Pm, Sun 12pm-5Pm The Mall at Chestnut Hill • (617) 965-2700 Holiday hours: mon-sat 9am-10Pm, sun 11am-7Pm contents COVER STORY PAS DE DEUX: Jaime Diaz and Kathleen Breen Combes dance their way across the stage in Boston Ballet’s beloved production 14 Holiday Happenings of The Nutcracker at The Opera Hit the Hub House. -

SPORTS WORLD Celebrating Boston’S Illustrious Sports Past and Present

what to do • where to go • what to see October 20–November 2, 2008 The OOfficialfficial Guide to BBOSTON OSTON HUBof the SPORTS WORLD Celebrating Boston’s Illustrious Sports Past and Present PLUS: New Skipjack’s Halloween Boston Opens at Events Around Vegetarian Patriot Place the Hub Food Festival panoramamagazine.com now iPhone and Windows® smartphone compatible! contents Get VIP treatment COVER STORY at Macy’s… including 14 Banner Days A team-by-team look at Boston’s pro sports franchises, exclusive savings! PLUS an inside look at The Sports Museum No trip to Boston is complete without visiting The World’s Most Famous Store! Put Macy’s on your must-see list and DEPARTMENTS HAVE A SEAT: Sit on seats from the old Boston Garden at discover the season’s hottest styles for the Sports Museum, home to a 6 around the hub you and your home, plus surprises and cornucopia of regional sports 6 NEWS & NOTES treasures and exhibits. Refer to excitement everywhere you look! Bring 10 DINING story, page 14. PHOTOBY this ad to the Gift Wrap Department 12 STYLE B OB PERACHIO at Macy's Downtown Crossing or the 13 ON EXHIBIT Executive Offices at Macy’s CambridgeSide 18 the hub directory Galleria to request your reserved-for- 19 CURRENT EVENTS visitors-only Macy’s Savings Pass, and 26 MUSEUMS & GALLERIES use it as often as you want to save 11%* 30 SIGHTSEEING throughout either store. 34 EXCURSIONS 37 MAPS Macy’s Downtown Crossing 43 FREEDOM TRAIL 450 Washington Street 45 SHOPPING Boston, Ma. 51 RESTAURANTS 617-357-3000 64 CLUBS & BARS Macy’s CambridgeSide Galleria 65 NEIGHBORHOODS 100 CambridgeSide Place Cambridge, Ma. -

Young Alumni Guide - Boston Notre Dame Club of Boston Welcome to the Notre Dame Club of Boston!

Young Alumni Guide - Boston Notre Dame Club of Boston Welcome to the Notre Dame Club of Boston! With Boston known to be a prime area for younger grads and professionals, we hope you are excited to be here in Beantown! In order to assist with your transition to the area, we have gathered some key information for you about Boston and the Club: • Introduction to Club activities/events and their locations • “Must see” sites and other recommended locations • Popular neighborhoods for young and recent alums • How to become involved in the Club/contacts and resources Young Alumni Guide – Boston 1 Select Alumni Club Events - Timing Admitted Students Reception ND @ Red Sox ND @ Pops Student Send-off Mass/Picnic Hesburgh Service Orientation Happy Hour Summer Service Program Christmas Mass Gamewatches @ Christmas Party Bleacher Bar UND Night – Annual Event * Please see our Club website at www.ndboston.com for additional information Young Alumni Guide – Boston 2 Select Alumni Club Events - Locations Christmas Party @ Mr. Dooley’s Game Watches @ Orientation Bleacher Bar Happy Hour @ Avenue One Red Sox Games @ Fenway Park Bookstore Basketball – Bingo Night @ Healthcare Boston Edition for Homeless Community Service @ Boston Food Bank Young Alumni Guide – Boston 3 Boston Top 10 “Must See” Sights 1. Fenway Park 2. Harvard Yard 3. M.I.T 4. Bunker Hill Monument 5. Boston Common & Public Gardens 6. Capitol Building (Golden Dome!) 7. Faneuil Hall/Quincy Market 8. Italian North End 9. Trinity Church/Copley Square 10. “Old State House” Young Alumni Guide – Boston -

Northbridge Legion Falls to Cherry Valley

Mailed free to requesting homes in Douglas, Northbridge and Uxbridge Vol. II, No. 36 Complimentary to homes by request ONLINE: WWW.BLACKSTONEVALLEYTRIBUNE.COM Friday, July 4, 2014 THIS WEEK’S QUOTE Northbridge Legion falls “Men are equal; it is not birth but virtue that to Cherry Valley makes the difference.” BY NICK ETHIER Voltaire SPORTS STAFF WRITER NORTHBRIDGE — Although they fell behind quickly, 2-0, the Cherry Valley Post 443 American Legion INSIDE baseball team played a strong game against Northbridge Post 343 on June Joy Richard photos 30 at Lasell Field. A2-3— LOCAL Douglas School Building Committee Chairman Mitch Cohen Behind the pitching of Tyler Simons poses for a photo on Monday, June 30, in front of a bank of A4-5— OPINION and a five-run third inning, Cherry lockers at the middle school. Cohen said he is happy to see Valley walked away 7-2 winners. A7— OBITUARIES the buildings on track and looks forward to getting students “They could have died when it was and staff moved in this fall. A9— SENIOR SCENE 2-0, but they stayed in it,” Cherry Valley manager Joel Hart said of his PORTS A11 — S team. B2 — CALENDAR Northbridge’s best inning was the EAL STATE first, which gave them the aforemen- Schools taking B4— R E tioned 2-0 advantage, but from there it B5 — LEGALS was Cherry Valley’s game. Northbridge scored its runs on a Dylan Jepsen (2 for 3) RBI single and shape LOCAL a Tommy Sperino RBI groundout, but Jepsen was left stranded on second base. -

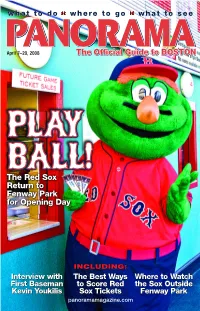

The Red Sox Return to Fenway Park for Opening Day

what to do • where to go • what to see April 7–20, 2008 Th eeOfOfficiaficialficial Guid eetoto BOSTON The Red Sox Return to Fenway Park for Opening Day INCLUDING:INCLUDING: Interview with The Best Ways Where to Watch First Baseman to Score Red the Sox Outside Kevin YoukilisYoukilis Sox TicketsTickets Fenway Park panoramamagazine.com BACK BY POPULAR DEMAND! OPENS JANUARY 31 ST FOR A LIMITED RUN! contents COVER STORY THE SPLENDID SPLINTER: A statue honoring Red Sox slugger Ted Williams stands outside Gate B at Fenway Park. 14 He’s On First Refer to story, page 14. PHOTO BY E THAN A conversation with Red Sox B. BACKER first baseman and fan favorite Kevin Youkilis PLUS: How to score Red Sox tickets, pre- and post-game hangouts and fun Sox quotes and trivia DEPARTMENTS "...take her to see 6 around the hub Menopause 6 NEWS & NOTES The Musical whe 10 DINING re hot flashes 11 NIGHTLIFE Men get s Love It tanding 12 ON STAGE !! Too! ovations!" 13 ON EXHIBIT - CBS Mornin g Show 19 the hub directory 20 CURRENT EVENTS 26 CLUBS & BARS 28 MUSEUMS & GALLERIES 32 SIGHTSEEING Discover what nearly 9 million fans in 35 EXCURSIONS 12 countries are laughing about! 37 MAPS 43 FREEDOM TRAIL on the cover: 45 SHOPPING Team mascot Wally the STUART STREET PLAYHOUSE • Boston 51 RESTAURANTS 200 Stuart Street at the Radisson Hotel Green Monster scores his opening day Red Sox 67 NEIGHBORHOODS tickets at the ticket ofofficefice FOR TICKETS CALL 800-447-7400 on Yawkey Way. 78 5 questions with… GREAT DISCOUNTS FOR GROUPS 15+ CALL 1-888-440-6662 ext. -

The Key West Aquarium CAST Are ESP Award Winners! Bob Bernreuter, Natonal Sales Manager for Historic Tours of America

The Key West Aquarium CAST are ESP Award Winners! Bob Bernreuter, Natonal Sales Manager for Historic Tours of America The H.T.A. Entertainment, Service, and People (E.S.P.) Award carpentry skills while they were building decks and exhibits. Everyone is normally presented to an individual who has gone beyond their had to pull extra duties, perform skills outside their job descriptions, normal call of duty in their given field of endeavor. However, in the and cover for each other. Throughout this major undertaking, the case of the Key West Aquarium, the whole CAST stepped up offering show never lost a beat. All of us at HTA headquarters are in awe of their time and talent to accomplish a complete makeover of the the transformation of this attraction. Greg used his artistic skills in oldest attraction in Key West. repairing and repainting the huge fish mounts on exhibit, such as the Built in 1935 by the FERA (Federal Emergency Relief great white shark, the hammerhead shark, the huge goliath grouper, Administration) the exhibits and general building dynamics were in and the monstrous manta ray. Robert Murphy, who was a contractor need of a facelift to attract a market that has become overexposed to in a previous life, oversaw the planning and construction of the decks hype. Saturated by sophisticated marketing, our guests today require and new exhibits, like Stingray Bay, the tank where guests can touch the latest in visual, audio, and tactile stimulation just to get their and feed cow nose rays and southern stingray pups. attention. Like having your picture taken holding a live alligator… or Through their determination, expertise, and dedication to our petting a live shark. -

Red Sox Community Relations RED SOX FOUNDATION STAFF COMMUNITY RELATIONS STAFF

COMMUNITY REPORT Red Sox Community Relations RED SOX FOUNDATION STAFF COMMUNITY RELATIONS STAFF Rebekah Salwasser Pam Kenn Executive Director Senior Vice President, Community, Alumni & Player Relations Michael Blume Program Specialist Sarah Narracci Senior Director, Community Virginia Fresne & Player Relations Development Coordinator Sheri Rosenberg Kirsten Martin Alumni & Player Relations Manager Senior Development Officer Olivia Irving Kathy Meins Community Relations Specialist “The work of the Red Sox Foundation reflects Executive Assistant the passion of our players, the generosity of Rico Mochizuki Assistant Director of Operations our fans, and the character of Red Sox Nation.” Tyler Petropulos Assistant Director of Programs Tom Werner, Red Sox Chairman Brad Schoonmaker Director of Programs Jake Siemering Senior Development Coordinator Jacob Urena Fellow Emily Van Dam Accounting Manager Jeff White Treasurer Lidia Zayas Program Specialist 2002 – 2018 Charitable Box Score: RED SOX FOUNDATION BOARD OF DIRECTORS RED SOX FOUNDATION DEAR FRIENDS, Thomas C. Werner 2019 was another extraordinary year for the Red Sox Foundation as we Chairman continued to excel and make history with our innovative programming and partnerships. The year was capped with an incredible recognition; Tim Wakefield the Foundation once again received the Allan H. Selig Award – the only Honorary Chairman MLB team Foundation to receive it twice. Since winning in 2010 for the Michael Egan Red Sox Scholars program, we were honored to win in 2019 for our Home David Friedman Base program. Chad Gifford As we look ahead into 2020, we are inspired to continue to make history and impact through our three core partners; Home Base, The Jimmy Fund, Linda Pizzuti Henry and The Dimock Center. -

Junto a Su Conducktor Navegarán Todos Los Puntos De Interés Que

Junto a su conDUCKtor navegarán todos los puntos de interés que distinguen a Boston como la cuna de libertad y una ciudad de primeros, desde la cúpula dorada de la cámara de representantes al Boston Common, del histórico vecindario The North End hacia la elegante Newbury Street, Quincy Market al Prudential Center y más! Justo cuando piensa que lo a visto todo, es tiempo de entrar al río Charles para una impresionante vista de Boston y Cambridge. ¡Venga y disfrute de la mejor introDUCKción a Boston! Información general Horario Las excursiones comienzan a las 9 a.m. desde el Museum of Science y Prudential Center. Visite nuestro sitio web para obtener información sobre las salidas desde el New England Aquarium. La última excursión normal sale una hora antes de la caída del sol. Las excursiones salen cada 30 a 60 minutos. Venta de Se pueden comprar boletos en persona el día de la excursión o hasta con 30 días de anticipación en nuestros lugares boletos de venta de boletos, por teléfono o en nuestro sitio web. Las tarifas de grupos son para 20 o más visitas y se pueden comprar llamando a ventas para grupos al 800-226-7442 Lugares Prudential Center, Museum of Science y New England Aquarium Duración de la excursión 80 minutos Temporada Siete (7) días por semana desde el primer día de la primavera (en Boston) hasta el último domingo en noviembre. Las excursiones durante las fiestas en diciembre salen del Prudential Center solamente los viernes, sábados y domingos. Tarifas de entradas 2019 (en dólares de EE.UU.) Adulto $42.99* Adultos en grupo $32.00** Estudiante/Jubilado/Militar $34.99* Estudiante/Jubilado/Militar en grupo $28.00** Niños de 3 a 11 años $28.99* Niños de 3 a 11 años en grupo $24.00** Niños menores de 3 años $10.50* Vehículo Duck privado (35 asientos) $1100.00** Pago adicional de $50 si requiere cargar o descargar pasajeros en otro lugar.