A Survey of Medieval Floor Tiles in St Andrews Cathedral Museum And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Aspects of the Architectural History of Kirkwall Cathedral Malcolm Thurlby*

Proc Antiqc So Scot, (1997)7 12 , 855-8 Aspects of the architectural history of Kirkwall Cathedral Malcolm Thurlby* ABSTRACT This paper considers intendedthe Romanesque formthe of Kirkwallof eastend Cathedraland presents further evidence failurethe Romanesque for ofthe crossing, investigates exactthe natureof its rebuilding and that of select areas of the adjacent transepts, nave and choir. The extension of the eastern arm is examined with particular attention to the lavish main arcades and the form of the great east window. Their place medievalin architecture Britainin exploredis progressiveand and conservative elements building ofthe evaluatedare context building. the ofthe in use ofthe INTRODUCTION sequence Th f constructioeo t Magnus'S f o n s Cathedra t Kirkwalla l , Orkney comples i , d xan unusual. The basic chronology was established by MacGibbon & Ross (1896, 259-92) and the accoune Orkneth n i ty Inventory e Royath f o l Commissio e Ancienth d Historican o an nt l Monuments of Scotland (RCAHMS 1946,113-25)(illus 1 & 2). The Romanesque cathedral was begun by Earl Rognvald in 1137. Construction moved slowly westwards into the nave before the crossing was rebuilt in the Transitional style and at the same time modifications were made to the transepts includin erectioe gpresene th th f no t square eastern chapels. Shortly after thi sstara t wa sextensioe madth eastere n eo th befor f m no n ar e returnin nave e worgo t th t thi n .A k o s stage no reason was given for the remodelling of the crossing and transepts in the late 12th century. -

The Adventure of the Stone of Scone - Ston the Return of Solar Pons, 1958

The Adventure of the Stone of Scone - Ston The Return of Solar Pons, 1958 Date Copper/December 25, 1930 Pattrick/December, 1935 The Case Parker is awakened at Pons just before 4 AM on Christmas morning. Bancroft is on his way over to Praed Street. Once he arrives, he tells them that the Stone of Scone, the ancient Coronation Stone of the Scottish people has been stolen from Westminster Abbey. It is a symbolic item and the English government wants it back with a minimum of embarrassment. Pons quickly determines that it was taken by three men and a woman and goes to work. Quotes This bids fair to be the merriest of Christmases! Comments Pons tells his brother that Bancroft must have come “on a matter of the utmost gravity.” He adds that it is not connected with the Foreign Office because of the hour. That seems a specious deduction, at best. Foreign Office affairs would certainly be likely to require immediate attention at any moment, twenty-four hours a day. Certainly, this is a police matter: the symbol of Scottish independence has been stolen. But Bancroft makes it clear that it is the government that is most concerned. Wouldn’t the issue be a Foreign Office matter as well? The Stone of Scone’s formal name is the Stone of Destiny, though the former name is used widely outside of Scotland. The kings of Scotland were crowned upon a throne built above the Stone of Destiny, which was “about twenty-six inches long and sixteen wide, and weights considerably over four hundred pounds, almost five.” Edward I conquered Scotland and took the stone back to England. -

4 Day Itinerary — Scotland’S Year of Stories 2022

Scotland’s Tay Country - 4 day itinerary — Scotland’s year of stories 2022 01. Fife Dunfermline Carnegie Library & Galleries Lindores Abbey Distillery At Dunfermline Carnegie Library & Galleries, your clients Lindores Abbey is the spiritual home of Scotch whisky, can explore the remarkable royal history and industrial where records indicate that the first whisky was produced by heritage of Dunfermline, one of Scotland’s ancient Tironensian Monks in 1494. After over 500 years, your clients capitals, as it is brought to life in this spectacular museum will be able to see single malt distillation once again flowing and gallery. The museum showcases the rich past of the from the copper stills. Private group tours can be arranged locality through six themes: Industry, Leisure & Recreation, and can be tailored to the group’s specific interests. The Transport, Conflict, Homes and Royal Dunfermline. The Apothecary experiences offer your clients a fantastic chance galleries include three impressive exhibition spaces to get ‘hands on’ in making their own delicious version of providing an opportunity for Dunfermline to display some Aqua Vitae. of Fife Council’s impressive art and museum collections. Abbey Road 1-7 Abbot Street Newburgh, KY14 6HH Dunfermline, KY12 7NL www.lindoresabbeydistillery.com www.onfife.com/dclg Link to Trade Site Link to Trade Site Distance between Lindores Abbey Distillery and British Golf Distance between Dunfermline Carnegie Library & Museum is 19.9 miles /32km. Galleries and Falkland Palace is 23.2 miles /37.3km. British Golf Museum Falkland Palace The British Golf Museum is a 5-star museum and contains the Falkland Palace was the largest collection of golf memorabilia in Europe. -

Excavations at Kelso Abbey Christophe Tabrahamrj * with Contribution Ceramie Th N So C Materia Eoiy B L N Cox, George Haggart Johd Yhursan N G T

Proc Antlqc So Scot, (1984), 365-404 Excavations at Kelso Abbey Christophe TabrahamrJ * With contribution ceramie th n so c materia Eoiy b l n Cox, George Haggart Johd yHursan n G t 'Here are to be seen the Ruines of an Ancient Monastery founde Kiny db g David' (John Slezer, Theatrum Scotlae) SUMMARY The following is a report on an archaeological investigation carried out in 1975 and 1976 on garden ground a little to the SE of the surviving architectural fragment of this Border abbey. Evidence was forthcoming of intensive occupation throughout the monastery's existence from the 16ththe 12th to centuries. area,The first utilized perhaps a masons' as lodge duringthe construction of the church and cloister, was subsequently cleared before the close of the 12th century to accommodate the infirmary hall and its associated buildings. This capacious structure, no doubt badly damaged during Warsthe Independence, of largelyhad beenof abandonedend the by the 15th century when remainingits walls were partially taken down anotherand dwelling erected upon the site. This too was destroyed in the following century, the whole area becoming a handy stone quarry for local inhabitants before reverting to open ground. INTRODUCTION sourca s i f regret o I e t that Kelso oldeste th , wealthiese th , mose th td powerfutan e th f o l four Border abbeys, should have been the one to have survived the least unimpaired. Nothing of e cloisteth r sav e outeth e r parlour remain t whas (illubu , t 4) survives e churcth s beef so hha n described 'of surpassing interest as one of the most spectacular achievements of Romanesque architecture in Scotland' (Cruden 1960, 60). -

Arbroath Abbey Final Report March 2019

Arbroath Abbey Final Report March 2019 Richard Oram Victoria Hodgson 0 Contents Preface 2 Introduction 3-4 Foundation 5-6 Tironensian Identity 6-8 The Site 8-11 Grants of Materials 11-13 The Abbey Church 13-18 The Cloister 18-23 Gatehouse and Regality Court 23-25 Precinct and Burgh Property 25-29 Harbour and Custom Rights 29-30 Water Supply 30-33 Milling 33-34 The Almshouse or Almonry 34-40 Lay Religiosity 40-43 Material Culture of Burial 44-47 Liturgical Life 47-50 Post-Reformation Significance of the Site 50-52 Conclusions 53-54 Bibliography 55-60 Appendices 61-64 1 Preface This report focuses on the abbey precinct at Arbroath and its immediately adjacent appendages in and around the burgh of Arbroath, as evidenced from the documentary record. It is not a history of the abbey and does not attempt to provide a narrative of its institutional development, its place in Scottish history, or of the men who led and directed its operations from the twelfth to sixteenth centuries. There is a rich historical narrative embedded in the surviving record but the short period of research upon which this document reports did not permit the writing of a full historical account. While the physical structure that is the abbey lies at the heart of the following account, it does not offer an architectural analysis of the surviving remains but it does interpret the remains where the documentary record permits parts of the fabric or elements of the complex to be identified. This focus on the abbey precinct has produced some significant evidence for the daily life of the community over the four centuries of its corporate existence, with detail recovered for ritual and burial in the abbey church, routines in the cloister, through to the process of supplying the convent with its food, drink and clothing. -

Robertson's Rant

ROBERTSON’S RANT The Newsletter of the Clan Donnachaidh Society —Mid- Atlantic Branch STRUAN RETURNS—1726 By James E. Fargo, FSA Scot VOLUME 9, ISSUE 2 English-Scottish relations after the 1707 Treaty of Union were strained at best. The imposition of new customs and excise duties on a wide range of commodi- MAY 2020 ties (including beer, home salt, linen, soap, etc.) previously untaxed was very unpopular. The previous level of taxation was not enough to cover the costs of Branch Officers the civil government. The English rightly believed that the Scots were evading taxation because of the enormous scale of smuggling and revenue fraud going President: on. Recent research has been able to confirm the scale of this evasion on one Sam Kistler product. Between 1707 and 1722, Scottish Glasgow merchants managed to evade duty on half of their tobacco imports from Virginia and Maryland. Vice President: Efforts along the coasts by the Board of Customs to collect unpaid taxes on Ron Bentz goods arriving by ships and found hidden in warehouses were met with violence against the customs officials. London needed custom revenue to pay down their Secretary/Treasurer: National Debt which had grown to finance the Spanish Succession War which Norman Dunkinson ended in 1713. In July 1724, King George I appointed General George Wade the new Command- er-in-Chief of His Majesty’s Forces in Scotland. That same year, the English gov- ernment of Sir Robert Walpole decided to implement a malt tax on Scotland to begin in June 1725. This attempt to generate more revenue raised the cost of ale and created a wave of popular anger with riots breaking out throughout the major cities. -

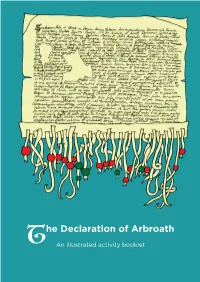

The Declaration of Arbroath: an Illustrated Activity Booklet

he Declaration of Arbroath T An illustrated activity booklet In this activity booklet, you can find out about the Declaration of Arbroath – a famous letter and one of Scotland’s most important historic documents. Use your imagination to draw, design and create. You can also colour in the illustrations! 3 What is the Declaration of Arbroath? he Declaration of Arbroath was a letter written 700 years ago in 1320, when the Scots wanted to stop King Edward II of England trying to rule over Scotland. TIt was sent by some of the most powerful people in Scotland to Pope John XXII. They wanted him to recognise Robert the Bruce as their king. As the Head of the Catholic Church, the Pope could help sort out disagreements between countries. The letter was written on parchment in Latin, a language used by the church. It was originally called the Barons’ Letter and a copy was made when it was written. Much later it became known as the Declaration of Arbroath. The copy is now looked after by National Records of Scotland in Edinburgh. 3 What’s it got to do with Arbroath? rbroath Abbey, on the east coast of Scotland, was chosenA as the place where the Declaration would be sealed and sent off to the Pope in France. The man in charge of the abbey, Abbot Bernard, was chancellor of Scotland and was responsible for all official documents for Robert the Bruce. Arbroath was also quite far away from England and next to the sea – so the letter could be sent safely by boat to France. -

Arbroath Abbey & Arbroath Abbey Abbot's House

Property in Care (PIC) ID: PIC006 & PIC007 Designations: Scheduled Monument (SM90018); Listed Building (LB21130 Category A, LB21131 Category A, LB21132 Category A, LB21133 Category A, LB21134 Category A, LB21135 Category B) Taken into State care: 1905 (Ownership) & 1929 (Guardianship) Last reviewed: 2015 HISTORIC ENVIRONMENT SCOTLAND STATEMENT OF SIGNIFICANCE ARBROATH ABBEY & ARBROATH ABBEY ABBOT’S HOUSE We continually revise our Statements of Significance, so they may vary in length, format and level of detail. While every effort is made to keep them up to date, they should not be considered a definitive or final assessment of our properties. Historic Environment Scotland – Scottish Charity No. SC045925 Principal Office: Longmore House, Salisbury Place, Edinburgh EH9 1SH Historic Environment Scotland – Scottish Charity No. SC045925 Principal Office: Longmore House, Salisbury Place, Edinburgh EH9 1SH HISTORIC ENVIRONMENT SCOTLAND STATEMENT OF SIGNIFICANCE ARBROATH ABBEY & ARBROATH ABBEY ABBOT’S HOUSE CONTENTS 1 Summary 2 1.1 Introduction 2 1.2 Statement of significance 2 2 Assessment of values 2 2.1 Background 2 2.2 Evidential values 3 2.3 Historical values 4 2.4 Architectural and artistic values 6 2.5 Landscape and aesthetic values 8 2.6 Natural heritage values 9 2.7 Contemporary/use values 9 3 Major gaps in understanding 10 4 Associated properties 10 5 Keywords 10 Bibliography 10 APPENDICES Appendix 1: Timeline 12 Historic Environment Scotland – Scottish Charity No. SC045925 Principal Office: Longmore House, Salisbury Place, Edinburgh EH9 1SH 1 1 Summary 1.1 Introduction The monument consists of the remains (now mainly fragmentary) of an outstandingly ambitious royal monastic foundation, which was planned by William I ‘the Lion’ (1165-1214), one of Scotland’s most revered medieval monarchs, as his own burial place. -

Sites-Guide.Pdf

EXPLORE SCOTLAND 77 fascinating historic places just waiting to be explored | 3 DISCOVER STORIES historicenvironment.scot/visit-a-place OF PEOPLE, PLACES & POWER Over 5,000 years of history tell the story of a nation. See brochs, castles, palaces, abbeys, towers and tombs. Explore Historic Scotland with your personal guide to our nation’s finest historic places. When you’re out and about exploring you may want to download our free Historic Scotland app to give you the latest site updates direct to your phone. ICONIC ATTRACTIONS Edinburgh Castle, Iona Abbey, Skara Brae – just some of the famous attractions in our care. Each of our sites offers a glimpse of the past and tells the story of the people who shaped a nation. EVENTS ALL OVER SCOTLAND This year, yet again we have a bumper events programme with Spectacular Jousting at two locations in the summer, and the return of festive favourites in December. With fantastic interpretation thrown in, there’s lots of opportunities to get involved. Enjoy access to all Historic Scotland attractions with our great value Explorer Pass – see the back cover for more details. EDINBURGH AND THE LOTHIANS | 5 Must See Attraction EDINBURGH AND THE LOTHIANS EDINBURGH CASTLE No trip to Scotland’s capital is complete without a visit to Edinburgh Castle. Part of The Old and New Towns 6 EDINBURGH CASTLE of Edinburgh World Heritage Site and standing A mighty fortress, the defender of the nation and majestically on top of a 340 million-year-old extinct a world-famous visitor attraction – Edinburgh Castle volcano, the castle is a powerful national symbol. -

Download Download

Proc Soc Antiq Scot, 125 (1995), 901-916 Lion hunt royaa : l tomb-effig Arbroatt ya h Abbey GGimsonS * ABSTRACT This paper summarizes resultsthe search a of evidencefor identifyto subjectthe tomb-effigya of of Frosterley (Durham) marble Arbroathat Abbey. effigyThe probably earlydatesthe to 14th century and is of a quality unique in Scotland. It was unearthed in the Abbey ruins in 1816 and thatat timewas thattaken be King of to William Lion,the founderAbbey.the of Since then, opinions have varied. searchThe involved examination similarof effigies north-eastin England and study of the iconography of kingship in Scotland. In addition, a family link between the subjects ofEnglish fourthe of effigiesKingand Robert I (Bruce) vein openedinquiry.new of a up It will be suggested that the whole material supports the proposition that the effigy is of King Williamonlythe Lion. is surviving the it Ifso, medieval a effigy of King Scotland.of evidenceThe also supports an inference that King Robert I was probably concerned in its provision. HISTORY Arbroat foue hth rAbbeyf o grea e ton , Tironensian abbey Scotlandn i s s foundewa , Kiny db g William the Lion in 1178. He endowed it richly and it remained one of the most important religious houses in the country. When the king died in 1214, he was buried in front of the high altar of the Abbey (Anderson 1922, vol 2, 400). The Abbey was not consecrated until 1223. Buildin s presumablgwa y complet l essentialal n i e theny b s n 1272I . e Abbe th ,s ver ywa y extensively damaged as the result of a violent storm and fire. -

Kelso Abbey Timeline

Kelso Abbey Timeline British Monarchy Historical Events Scottish Monarchy Kelso and the Environs English Monarchy 1153 David succeeded by his 1128 grandson Malcolm IV who Monks moved to Kelso soon after confirmed the just across the river abbey’s charter from David’s Royal Alexander I Burgh of Roxburgh 1107-1124 1178 William I Arbroath Abbey David I Henry II “the Lion” founded by monks 1100 1124-1153 1154-1189 1165-1214 from Kelso 1200 Henry I Stephen Malcolm IV Richard I 1100-1135 1135-1154 1153-1165 “Lion Heart” C 1170 1189-1199 Abbot John travelled to 1138 Rome and was David I intervened in the civil awarded right 1113 1124 1152 John war in England - defeated at of abbots to Prince David, Earl of David succeeded David’s only son 1199-1216 the Battle of the Standard wear mitre Cumbria brought monks his brother Henry buried from Tiron to Selkirk Alexander as before high altar King of Scotland of Kelso Abbey 1175 1191 William the Lion, captured Abbey of Lindores in battle did homage to founded by monks Henry II - later bought it from Kelso back from Richard I Kelso Abbey Timeline British Monarchy Historical Events Scottish Monarchy Kelso and the Environs English Monarchy 1295 King John signed alliance with France against England - the “Auld Alliance” 1263 1214 Battle of Largs 1290 recovered Hebrides Abbot Henry attended Abbot Richard of Kelso for Scotland General Church Council supported claim of John in Rome Balliol to Scottish throne 1215 Alexander III 1286 King John of England 1249-1286 Accidental death 1200 signed the Magna Carta -

Reasons to Visit Angus Angus… a Step Away from the Everyday

50 Reasons to Visit Angus Angus… a step away from the everyday Angus has it all, from the breathtaking scenery of the rolling hills and glens to the sandy, white beaches along the stunning coastline in the east of Scotland. There are seven towns in Angus - Arbroath, Brechin, Carnoustie, Forfar, Kirriemuir, Monifieth and Montrose, each with its own unique character and attractions. Carnoustie Championship will host The Open in 2018 – for the eighth time. 1 Discover our outstanding scenery. From golden 6 Visit Glamis Castle , the fairytale of the Earls beaches to lush green fields to towering, craggy of Strathmore - Glamis Castle, setting for several mountains, Angus has the perfect backdrop. scenes in Shakespeare’s Macbeth and reputed to be one of Scotland’s most haunted places. 2 Play golf to your heart’s content. As well as being home to Carnoustie Championship, Find out more about the early days of 7 Carnoustie Country is home to 33 other superb golf aviation at Montrose Air Station Heritage Centre . courses, all within an hour’s drive. This award-winning museum is located in the restored buildings and hangars of the historic air 3 Visit Arbroath Abbey – in medieval times, this station, which opened in 1913, and features an was the most powerful and wealthiest monastery in outstanding collection of vintage and replica Scotland and on April 6, 1320, the nobles of aircraft, including a Spitfire, a Sopwith Camel and Scotland gathered here to sign the Declaration of a BE2a. Arbroath, the foundation stone of the nation of Scotland. Step on board the magnificent ship that took 8 Captain Scott to Antarctica at RRS Discovery, the 4 Relive the glory days of train travel at award-winning visitor centre on the banks of the Caledonian Railway , where vintage steam and River Tay.