2019 Role-Playing on Stage.Pages

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Shakespeare and London Programme

andShakespeare London A FREE EXHIBITION at London Metropolitan Archives from 28 May to 26 September 2013, including, at advertised times, THE SHAKESPEARE DEED A property deed signed by Mr. William Shakespeare, one of only six known examples of his signature. Also featuring documents from his lifetime along with maps, photographs, prints and models which explore his relationship with the great metropolis of LONDONHighlights will include the great panoramas of London by Hollar and Visscher, a wall of portraits of Mr Shakespeare, Mr. David Garrick’s signature, 16th century maps of the metropolis, 19th century playbills, a 1951 wooden model of The Globe Theatre and ephemera, performance recording and a gown from Shakespeare’s Globe. andShakespeare London In 1613 William Shakespeare purchased a property in Blackfriars, close to the Blackfriars Theatre and just across the river from the Globe Theatre. These were the venues used by The Kings Men (formerly the Lord Chamberlain’s Men) the performance group to which he belonged throughout most of his career. The counterpart deed he signed during the sale is one of the treasures we care for in the City of London’s collections and is on public display for the first time at London Metropolitan Archives. Celebrating the 400th anniversary of the document, this exhibition explores Shakespeare’s relationship with London through images, documents and maps drawn from the archives. From records created during his lifetime to contemporary performances of his plays, these documents follow the development of his work by dramatists and the ways in which the ‘bardologists’ have kept William Shakespeare alive in the fabric of the city through the centuries. -

Hamlet-Production-Guide.Pdf

ASOLO REP EDUCATION & OUTREACH PRODUCTION GUIDE 2016 Tour PRODUCTION GUIDE By WILLIAM SHAKESPEARE ASOLO REP Adapted and Directed by JUSTIN LUCERO EDUCATION & OUTREACH TOURING SEPTEMBER 27 - NOVEMBER 22 ASOLO REP LEADERSHIP TABLE OF CONTENTS Producing Artistic Director WHAT TO EXPECT.......................................................................................1 MICHAEL DONALD EDWARDS WHO CAN YOU TRUST?..........................................................................2 Managing Director LINDA DIGABRIELE PEOPLE AND PLOT................................................................................3 FSU/Asolo Conservatory Director, ADAPTIONS OF SHAKESPEARE....................................................................5 Associate Director of Asolo Rep GREG LEAMING FROM THE DIRECTOR.................................................................................6 SHAPING THIS TEXT...................................................................................7 THE TRAGEDY OF HAMLET CREATIVE TEAM FACT IN THE FICTION..................................................................................9 Director WHAT MAKES A GHOST?.........................................................................10 JUSTIN LUCERO UPCOMING OPPORTUNITIES......................................................................11 Costume Design BECKI STAFFORD Properties Design MARLÈNE WHITNEY WHAT TO EXPECT Sound Design MATTHEW PARKER You will see one of Shakespeare’s most famous tragedies shortened into a 45-minute Fight Choreography version -

Text Pages Layout MCBEAN.Indd

Introduction The great photographer Angus McBean has stage performers of this era an enduring power been celebrated over the past fifty years chiefly that carried far beyond the confines of their for his romantic portraiture and playful use of playhouses. surrealism. There is some reason. He iconised Certainly, in a single session with a Yankee Vivien Leigh fully three years before she became Cleopatra in 1945, he transformed the image of Scarlett O’Hara and his most breathtaking image Stratford overnight, conjuring from the Prospero’s was adapted for her first appearance in Gone cell of his small Covent Garden studio the dazzle with the Wind. He lit the touchpaper for Audrey of the West End into the West Midlands. (It is Hepburn’s career when he picked her out of a significant that the then Shakespeare Memorial chorus line and half-buried her in a fake desert Theatre began transferring its productions to advertise sun-lotion. Moreover he so pleased to London shortly afterwards.) In succeeding The Beatles when they came to his studio that seasons, acknowledged since as the Stratford he went on to immortalise them on their first stage’s ‘renaissance’, his black-and-white magic LP cover as four mop-top gods smiling down continued to endow this rebirth with a glamour from a glass Olympus that was actually just a that was crucial in its further rise to not just stairwell in Soho. national but international pre-eminence. However, McBean (the name is pronounced Even as his photographs were created, to rhyme with thane) also revolutionised British McBean’s Shakespeare became ubiquitous. -

Christopher Plummer

Christopher Plummer "An actor should be a mystery," Christopher Plummer Introduction ........................................................................................ 3 Biography ................................................................................................................................. 4 Christopher Plummer and Elaine Taylor ............................................................................. 18 Christopher Plummer quotes ............................................................................................... 20 Filmography ........................................................................................................................... 32 Theatre .................................................................................................................................... 72 Christopher Plummer playing Shakespeare ....................................................................... 84 Awards and Honors ............................................................................................................... 95 Christopher Plummer Introduction Christopher Plummer, CC (born December 13, 1929) is a Canadian theatre, film and television actor and writer of his memoir In "Spite of Myself" (2008) In a career that spans over five decades and includes substantial roles in film, television, and theatre, Plummer is perhaps best known for the role of Captain Georg von Trapp in The Sound of Music. His most recent film roles include the Disney–Pixar 2009 film Up as Charles Muntz, -

Reminder List of Productions Eligible for the 90Th Academy Awards Alien

REMINDER LIST OF PRODUCTIONS ELIGIBLE FOR THE 90TH ACADEMY AWARDS ALIEN: COVENANT Actors: Michael Fassbender. Billy Crudup. Danny McBride. Demian Bichir. Jussie Smollett. Nathaniel Dean. Alexander England. Benjamin Rigby. Uli Latukefu. Goran D. Kleut. Actresses: Katherine Waterston. Carmen Ejogo. Callie Hernandez. Amy Seimetz. Tess Haubrich. Lorelei King. ALL I SEE IS YOU Actors: Jason Clarke. Wes Chatham. Danny Huston. Actresses: Blake Lively. Ahna O'Reilly. Yvonne Strahovski. ALL THE MONEY IN THE WORLD Actors: Christopher Plummer. Mark Wahlberg. Romain Duris. Timothy Hutton. Charlie Plummer. Charlie Shotwell. Andrew Buchan. Marco Leonardi. Giuseppe Bonifati. Nicolas Vaporidis. Actresses: Michelle Williams. ALL THESE SLEEPLESS NIGHTS AMERICAN ASSASSIN Actors: Dylan O'Brien. Michael Keaton. David Suchet. Navid Negahban. Scott Adkins. Taylor Kitsch. Actresses: Sanaa Lathan. Shiva Negar. AMERICAN MADE Actors: Tom Cruise. Domhnall Gleeson. Actresses: Sarah Wright. AND THE WINNER ISN'T ANNABELLE: CREATION Actors: Anthony LaPaglia. Brad Greenquist. Mark Bramhall. Joseph Bishara. Adam Bartley. Brian Howe. Ward Horton. Fred Tatasciore. Actresses: Stephanie Sigman. Talitha Bateman. Lulu Wilson. Miranda Otto. Grace Fulton. Philippa Coulthard. Samara Lee. Tayler Buck. Lou Lou Safran. Alicia Vela-Bailey. ARCHITECTS OF DENIAL ATOMIC BLONDE Actors: James McAvoy. John Goodman. Til Schweiger. Eddie Marsan. Toby Jones. Actresses: Charlize Theron. Sofia Boutella. 90th Academy Awards Page 1 of 34 AZIMUTH Actors: Sammy Sheik. Yiftach Klein. Actresses: Naama Preis. Samar Qupty. BPM (BEATS PER MINUTE) Actors: 1DKXHO 3«UH] %LVFD\DUW $UQDXG 9DORLV $QWRLQH 5HLQDUW] )«OL[ 0DULWDXG 0«GKL 7RXU« Actresses: $GªOH +DHQHO THE B-SIDE: ELSA DORFMAN'S PORTRAIT PHOTOGRAPHY BABY DRIVER Actors: Ansel Elgort. Kevin Spacey. Jon Bernthal. Jon Hamm. Jamie Foxx. -

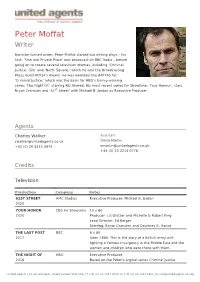

Peter Moffat Writer

Peter Moffat Writer Barrister turned writer, Peter Moffat started out writing plays – his first, ‘Fine and Private Place’ was broadcast on BBC Radio – before going on to create several television dramas, including ‘Criminal Justice, ‘Silk’ and ‘North Square,’ which he won the Broadcasting Press Guild Writer’s Award. He was awarded two BAFTAS for ‘Criminal Justice,’ which was the basis for HBO’s Emmy-winning series ‘The Night Of,’ starring Riz Ahmed. His most recent series for Showtime, ‘Your Honour,’ stars Bryan Cranston and ‘61st Street’ with Michael B. Jordan as Executive Producer. Agents Charles Walker Assistant [email protected] Olivia Martin +44 (0) 20 3214 0874 [email protected] +44 (0) 20 3214 0778 Credits Television Production Company Notes 61ST STREET AMC Studios Executive Producer: Michael B. Jordan 2020 YOUR HONOR CBS for Showtime 10 x 60 2020 Producer: Liz Glotzer and Michelle & Robert King Lead Director: Ed Berger Starring: Bryan Cranston and Courtney B. Vance THE LAST POST BBC 6 x 60 2017 Aden 1965. This is the story of a British army unit fighting a Yemeni insurgency in the Middle East and the women and children who were there with them. THE NIGHT OF HBO Executive Producer 2016 Based on the Peter's orginal series Criminal Justice United Agents | 12-26 Lexington Street London W1F OLE | T +44 (0) 20 3214 0800 | F +44 (0) 20 3214 0801 | E [email protected] Production Company Notes UNDERCOVER BBC1 6 x60' with Sophie Okonedo and Adrian Lester, Denis 2015 Haysbert Director James Hawes, Exec Producer Peter Moffat THE VILLAGE series Company Pictures 6 x 60' with John Simm, Maxine Peake, Juliet Stevenson 1 / BBC1 Producer: Emma Burge; Director: Antonia Bird 2013 SILK 2 BBC1 6 x 60' With Maxine Peake, Rupert Penry Jones, Frances 2012 Barber, and Neil Stuke Producer: Richard Stokes; Directors: Alice Troughton, Jeremy Webb, Peter Hoar SILK BBC1 6 x 60' 2011 With Maxine Peake, Rupert Penry Jones, Natalie Dormer, Tom Hughes and Neil Stuke. -

Playing Shakespeare with Deutsche Bank Production of Twelfth Night

2016 shakespeare’s globe Annual review contents Welcome 5 Theatre: The Globe 8 Theatre: The Sam Wanamaker Playhouse 14 Celebrating Shakespeare’s 400th Anniversary 20 Globe Education – Inspiring Young People 30 Globe Education – Learning for All 33 Exhibition & Tour 36 Catering, Retail and Hospitality 37 Widening Engagement 38 How We Made It & How We Spent It 41 Looking Forward 42 Last Words 45 Thank You! – Our Stewards 47 Thank You! – Our Supporters 48 Who’s Who 50 The Playing Shakespeare with Deutsche Bank production of Twelfth Night. Photo: Cesare de Giglio The Little Matchgirl and Other Happier Tales. Photo: Steve Tanner WELCOME 2016 – a momentous year – in which the world celebrated the richness of Shakespeare’s legacy 400 years after his death. Shakespeare’s Globe is proud to have played a part in those celebrations in 197 countries and led the festivities in London, where Shakespeare wrote and worked. Our Globe to Globe Hamlet tour travelled 193,000 miles before coming home for a final emotional performance in the Globe to mark the end, not just of this phenomenal worldwide journey, but the artistic handover from Dominic Dromgoole to Emma Rice. A memorable season of late Shakespeare plays in the Sam Wanamaker Playhouse and two outstanding Globe transfers in the West End ran concurrently with the last leg of the Globe to Globe Hamlet tour. On Shakespeare’s birthday, 23 April, we welcomed President Obama to the Globe. Actors performed scenes from the late plays running in the Sam Wanamaker Playhouse at Southwark Cathedral, a service which was the only major civic event to mark the anniversary in London and was attended by our Patron, HRH the Duke of Edinburgh. -

Frank Grace – Interview Transcript

THEATRE ARCHIVE PROJECT http://sounds.bl.uk Frank Grace – interview transcript Interviewer: Clare Brewer 8 December 2008 Theatre goer. Anna Lucasta; Windsor Rep; The Gioconda Smile; September Tide; The Second Mrs Tanqueray; Oklahoma; Annie Get your Gun; Shakespeare; The Old Vic; Peter Brook; Olivier; Amateur Theatre; Woolford; Look back In Anger; Encore; Theatre Cruelty; Roots; Tis Pity She’s a Whore; A View From the Bridge; Censorship; Theatre Clubs; The Bald Prima Donna; Oh What a Lovely War; Arthur Miller. This transcript has been edited by the interviewee and thus differs in places from the recording. CB: How did you first become interested in theatre? FG: I suppose through [act]ing at school, but in terms of any serious theatre going I suppose it goes back to the late 1940’s... interestingly enough, when I re-looked at the [programmes] that I have got, the first play that I saw [in] the West End was most unusual for the late 1940’s, it was a play called Anna Lucasta,an American play; what was unusual for the 1940s was that it was an all black cast. CB: Really… FG: And it was about a prostitute and my parents took me [laughs] and I think they must have been slightly worried because I was fourteen at the time and it was one of my first experiences. But that was not typical of the first sort of phase of my theatre-going between that moment in 1949 and about 1951 I suppose and [after where] something dramatic begins to happen, I think. -

Venus and Adonis the Rape of Lucrece

NA432912 Venus and Adonis Booklet 5-9-6 7/9/06 1:16 pm Page 1 William Shakespeare THE COMPLETE Venus and Adonis TEXT The Rape of Lucrece UNABRIDGED POETRY Read by Eve Best, Clare Corbett, David Burke and cast 3 Compact Discs NA432912 Venus and Adonis Booklet 5-9-6 7/9/06 1:16 pm Page 2 CD 1 Venus and Adonis 1 Even as the sun with purple... 5:07 2 Upon this promise did he raise his chin... 5:19 3 By this the love-sick queen began to sweat... 5:00 4 But lo! from forth a copse that neighbours by... 4:56 5 He sees her coming, and begins to glow... 4:32 6 'I know not love,' quoth he, 'nor will know it...' 4:25 7 The night of sorrow now is turn'd to day... 4:13 8 Now quick desire hath caught the yielding prey... 4:06 9 'Thou hadst been gone,' quoth she, 'sweet boy, ere this...' 5:15 10 'Lie quietly, and hear a little more...' 6:02 11 With this he breaketh from the sweet embrace... 3:25 12 This said, she hasteth to a myrtle grove... 5:27 13 Here overcome, as one full of despair... 4:39 14 As falcon to the lure, away she flies... 6:15 15 She looks upon his lips, and they are pale... 4:46 Total time on CD 1: 73:38 2 NA432912 Venus and Adonis Booklet 5-9-6 7/9/06 1:16 pm Page 3 CD 2 The Rape of Lucrece 1 From the besieged Ardea all in post.. -

Shakespeare on Film, Video & Stage

William Shakespeare on Film, Video and Stage Titles in bold red font with an asterisk (*) represent the crème de la crème – first choice titles in each category. These are the titles you’ll probably want to explore first. Titles in bold black font are the second- tier – outstanding films that are the next level of artistry and craftsmanship. Once you have experienced the top tier, these are where you should go next. They may not represent the highest achievement in each genre, but they are definitely a cut above the rest. Finally, the titles which are in a regular black font constitute the rest of the films within the genre. I would be the first to admit that some of these may actually be worthy of being “ranked” more highly, but it is a ridiculously subjective matter. Bibliography Shakespeare on Silent Film Robert Hamilton Ball, Theatre Arts Books, 1968. (Reissued by Routledge, 2016.) Shakespeare and the Film Roger Manvell, Praeger, 1971. Shakespeare on Film Jack J. Jorgens, Indiana University Press, 1977. Shakespeare on Television: An Anthology of Essays and Reviews J.C. Bulman, H.R. Coursen, eds., UPNE, 1988. The BBC Shakespeare Plays: Making the Televised Canon Susan Willis, The University of North Carolina Press, 1991. Shakespeare on Screen: An International Filmography and Videography Kenneth S. Rothwell, Neil Schuman Pub., 1991. Still in Movement: Shakespeare on Screen Lorne M. Buchman, Oxford University Press, 1991. Shakespeare Observed: Studies in Performance on Stage and Screen Samuel Crowl, Ohio University Press, 1992. Shakespeare and the Moving Image: The Plays on Film and Television Anthony Davies & Stanley Wells, eds., Cambridge University Press, 1994. -

SHIRCORE Jenny

McKinney Macartney Management Ltd JENNY SHIRCORE - Make-Up and Hair Designer 2003 Women in Film Award for Best Technical Achievement Member of The Academy of Motion Picture Arts & Sciences THE DIG Director: Simon Stone. Producers: Murray Ferguson, Gabrielle Tana and Ellie Wood. Starring: Lily James, Ralph Fiennes and Carey Mulligan. BBC Films. BAFTA Nomination 2021 - Best Make-Up & Hair KINGSMAN: THE GREAT GAME Director: Matthew Vaughn. Producer: Matthew Vaughn. Starring: Ralph Fiennes and Tom Holland. Marv Films / Twentieth Century Fox. THE AERONAUTS Director: Tom Harper. Producers: Tom Harper, David Hoberman and Todd Lieberman. Starring: Felicity Jones and Eddie Redmayne. Amazon Studios. MARY QUEEN OF SCOTS Director: Josie Rourke. Producers: Tim Bevan, Eric Fellner and Debra Hayward. Starring: Margot Robbie, Saoirse Ronan and Joe Alwyn. Focus Features / Working Title Films. Academy Award Nomination 2019 - Best Make-Up & Hairstyling BAFTA Nomination 2019 - Best Make-Up & Hair THE NUTCRACKER & THE FOUR REALMS Director: Lasse Hallström. Producers: Mark Gordon, Larry J. Franco and Lindy Goldstein. Starring: Keira Knightley, Morgan Freeman, Helen Mirren and Misty Copeland. The Walt Disney Studios / The Mark Gordon Company. WILL Director: Shekhar Kapur. Exec. Producers: Alison Owen and Debra Hayward. Starring: Laurie Davidson, Colm Meaney and Mattias Inwood. TNT / Ninth Floor UK Productions. Gable House, 18 – 24 Turnham Green Terrace, London W4 1QP Tel: 020 8995 4747 E-mail: [email protected] www.mckinneymacartney.com VAT Reg. No: 685 1851 06 JENNY SHIRCORE Contd … 2 BEAUTY & THE BEAST Director: Bill Condon. Producers: Don Hahn, David Hoberman and Todd Lieberman. Starring: Emma Watson, Dan Stevens, Emma Thompson and Ian McKellen. Disney / Mandeville Films. -

Quentin Tarantino Retro

ISSUE 59 AFI SILVER THEATRE AND CULTURAL CENTER FEBRUARY 1– APRIL 18, 2013 ISSUE 60 Reel Estate: The American Home on Film Loretta Young Centennial Environmental Film Festival in the Nation's Capital New African Films Festival Korean Film Festival DC Mr. & Mrs. Hitchcock Screen Valentines: Great Movie Romances Howard Hawks, Part 1 QUENTIN TARANTINO RETRO The Roots of Django AFI.com/Silver Contents Howard Hawks, Part 1 Howard Hawks, Part 1 ..............................2 February 1—April 18 Screen Valentines: Great Movie Romances ...5 Howard Hawks was one of Hollywood’s most consistently entertaining directors, and one of Quentin Tarantino Retro .............................6 the most versatile, directing exemplary comedies, melodramas, war pictures, gangster films, The Roots of Django ...................................7 films noir, Westerns, sci-fi thrillers and musicals, with several being landmark films in their genre. Reel Estate: The American Home on Film .....8 Korean Film Festival DC ............................9 Hawks never won an Oscar—in fact, he was nominated only once, as Best Director for 1941’s SERGEANT YORK (both he and Orson Welles lost to John Ford that year)—but his Mr. and Mrs. Hitchcock ..........................10 critical stature grew over the 1960s and '70s, even as his career was winding down, and in 1975 the Academy awarded him an honorary Oscar, declaring Hawks “a giant of the Environmental Film Festival ....................11 American cinema whose pictures, taken as a whole, represent one of the most consistent, Loretta Young Centennial .......................12 vivid and varied bodies of work in world cinema.” Howard Hawks, Part 2 continues in April. Special Engagements ....................13, 14 Courtesy of Everett Collection Calendar ...............................................15 “I consider Howard Hawks to be the greatest American director.