Memorandum on the Issue of Who Represents the State

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Appendix File Anes 1988‐1992 Merged Senate File

Version 03 Codebook ‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐ CODEBOOK APPENDIX FILE ANES 1988‐1992 MERGED SENATE FILE USER NOTE: Much of his file has been converted to electronic format via OCR scanning. As a result, the user is advised that some errors in character recognition may have resulted within the text. MASTER CODES: The following master codes follow in this order: PARTY‐CANDIDATE MASTER CODE CAMPAIGN ISSUES MASTER CODES CONGRESSIONAL LEADERSHIP CODE ELECTIVE OFFICE CODE RELIGIOUS PREFERENCE MASTER CODE SENATOR NAMES CODES CAMPAIGN MANAGERS AND POLLSTERS CAMPAIGN CONTENT CODES HOUSE CANDIDATES CANDIDATE CODES >> VII. MASTER CODES ‐ Survey Variables >> VII.A. Party/Candidate ('Likes/Dislikes') ? PARTY‐CANDIDATE MASTER CODE PARTY ONLY ‐‐ PEOPLE WITHIN PARTY 0001 Johnson 0002 Kennedy, John; JFK 0003 Kennedy, Robert; RFK 0004 Kennedy, Edward; "Ted" 0005 Kennedy, NA which 0006 Truman 0007 Roosevelt; "FDR" 0008 McGovern 0009 Carter 0010 Mondale 0011 McCarthy, Eugene 0012 Humphrey 0013 Muskie 0014 Dukakis, Michael 0015 Wallace 0016 Jackson, Jesse 0017 Clinton, Bill 0031 Eisenhower; Ike 0032 Nixon 0034 Rockefeller 0035 Reagan 0036 Ford 0037 Bush 0038 Connally 0039 Kissinger 0040 McCarthy, Joseph 0041 Buchanan, Pat 0051 Other national party figures (Senators, Congressman, etc.) 0052 Local party figures (city, state, etc.) 0053 Good/Young/Experienced leaders; like whole ticket 0054 Bad/Old/Inexperienced leaders; dislike whole ticket 0055 Reference to vice‐presidential candidate ? Make 0097 Other people within party reasons Card PARTY ONLY ‐‐ PARTY CHARACTERISTICS 0101 Traditional Democratic voter: always been a Democrat; just a Democrat; never been a Republican; just couldn't vote Republican 0102 Traditional Republican voter: always been a Republican; just a Republican; never been a Democrat; just couldn't vote Democratic 0111 Positive, personal, affective terms applied to party‐‐good/nice people; patriotic; etc. -

CONGRESSIONAL RECORD—SENATE June 10, 1999

June 10, 1999 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD—SENATE 12395 In the essay which helped her win the Louisiana was blessed with John big heart, who dreamed big dreams and competition over tens of thousands of McKeithen’s strong, determined leader- left an enormous legacy in his wake. others, Leslie wrote that despite the ship at a time when a lesser man, with We know that all our colleagues join us pity, the lack of understanding, and lesser convictions, might have ex- in expressing their deepest sympathy even the alienation of other people, she ploited racial tensions for political to his wife, Marjorie, his children and never once lost faith in her own ability gain. his grandchildren.∑ to focus on her goals. ‘‘In my heart,’’ In fact, throughout the South, f she said, ‘‘I know my dreams are great- McKeithen had plenty of mentors had TRIBUTE TO ELLIOTT HAYNES er than the forces of adversity and I he wanted to follow such a course. But trust that, by the way of hope and for- Governor McKeithen was decent ∑ Mr. JEFFORDS. Mr. President, I rise titude, I shall make these dreams a re- enough, tolerant enough and principled today to pay tribute to Elliott Haynes, ality.’’ enough to resist any urge for race bait- a great American and Vermonter, who And so she has. Yet, what is perhaps ing. In his own, unique way, to borrow passed away on May 19, of this year. even more remarkable than the cour- a phrase from Robert Frost, he took Elliott served his country and his com- age and determination with which she the road less traveled and that made munity in so many ways, and I feel pursued her dreams, is the humility all the difference. -

Supplement 1

*^b THE BOOK OF THE STATES .\ • I January, 1949 "'Sto >c THE COUNCIL OF STATE'GOVERNMENTS CHICAGO • ••• • • ••'. •" • • • • • 1 ••• • • I* »• - • • . * • ^ • • • • • • 1 ( • 1* #* t 4 •• -• ', 1 • .1 :.• . -.' . • - •>»»'• • H- • f' ' • • • • J -•» J COPYRIGHT, 1949, BY THE COUNCIL OF STATE GOVERNMENTS jk •J . • ) • • • PBir/Tfili i;? THE'UNIfTED STATES OF AMERICA S\ A ' •• • FOREWORD 'he Book of the States, of which this volume is a supplement, is designed rto provide an authoritative source of information on-^state activities, administrations, legislatures, services, problems, and progressi It also reports on work done by the Council of State Governments, the cpm- missions on interstate cooperation, and other agencies concepned with intergovernmental problems. The present suppkinent to the 1948-1949 edition brings up to date, on the basis of information receivjed.from the states by the end of Novem ber, 1948^, the* names of the principal elective administrative officers of the states and of the members of their legislatures. Necessarily, most of the lists of legislators are unofficial, final certification hot having been possible so soon after the election of November 2. In some cases post election contests were pending;. However, every effort for accuracy has been made by state officials who provided the lists aiid by the CouncJLl_ of State Governments. » A second 1949. supplement, to be issued in July, will list appointive administrative officers in all the states, and also their elective officers and legislators, with any revisions of the. present rosters that may be required. ^ Thus the basic, biennial ^oo/t q/7^? States and its two supplements offer comprehensive information on the work of state governments, and current, convenient directories of the men and women who constitute those governments, both in their administrative organizations and in their legislatures. -

Ronald Reagan, Louisiana, and the 1980 Presidential Election Matthew Ad Vid Caillet Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Master's Theses Graduate School 2011 "Are you better off "; Ronald Reagan, Louisiana, and the 1980 Presidential election Matthew aD vid Caillet Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Caillet, Matthew David, ""Are you better off"; Ronald Reagan, Louisiana, and the 1980 Presidential election" (2011). LSU Master's Theses. 2956. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses/2956 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Master's Theses by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ―ARE YOU BETTER OFF‖; RONALD REAGAN, LOUISIANA, AND THE 1980 PRESIDENTIAL ELECTION A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in The Department of History By Matthew David Caillet B.A. and B.S., Louisiana State University, 2009 May 2011 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I am indebted to many people for the completion of this thesis. Particularly, I cannot express how thankful I am for the guidance and assistance I received from my major professor, Dr. David Culbert, in researching, drafting, and editing my thesis. I would also like to thank Dr. Wayne Parent and Dr. Alecia Long for having agreed to serve on my thesis committee and for their suggestions and input, as well. -

Republican Primary State of Tennessee Presidential Preference

State of Tennessee March 6, 2012 Republican Primary Presidential Preference 1 . Michele Bachmann 6 . Rick Perry 2 . Newt Gingrich 7 . Charles "Buddy" Roemer 3 . Jon Huntsman 8 . Mitt Romney 4 . Gary Johnson 9 . Rick Santorum 5 . Ron Paul 10. Uncommitted 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 ANDERSON County Precincts: Andersonville 0 115 2 0 31 2 1 121 170 4 Briceville 1 20 0 0 7 1 1 19 21 2 Blockhouse Valley 0 25 0 0 14 0 0 40 37 2 Clinton 0 127 2 0 41 2 1 188 228 4 Clinton High 2 64 3 0 18 5 0 99 116 2 Claxton 3 172 2 0 60 1 1 166 286 4 Clinton Middle 0 27 1 0 21 1 0 30 84 3 Clinch Valley 0 86 0 0 25 1 0 106 162 6 Dutch Valley 0 53 0 1 20 2 0 59 111 1 Emory Valley 2 102 5 0 46 1 1 208 130 3 Fairview 1 53 0 0 20 0 0 70 130 1 Glen Alpine 2 27 1 0 11 1 0 34 60 0 Glenwood 1 66 0 0 38 0 0 104 92 0 Hendrix Creek 1 101 6 0 41 2 0 208 122 3 Highland View 1 25 0 0 30 0 2 42 55 5 Lake City 0 25 0 1 7 0 0 19 40 0 Lake City Middle 2 94 2 1 24 2 0 89 136 3 Marlow 1 54 0 0 18 1 0 49 62 2 North Clinton 3 50 1 0 13 1 0 70 88 1 Norris 1 48 2 0 44 1 0 60 78 5 Norwood 6 39 0 0 20 2 0 50 75 0 Oak Ridge City Hall 0 27 0 0 21 0 2 36 39 1 Pine Valley 2 67 0 3 55 1 3 74 122 3 Robertsville 1 31 1 2 13 0 2 59 61 1 Rosedale 0 4 0 0 1 1 0 6 17 0 South Clinton 5 63 2 1 19 2 0 67 105 2 Tri-County 1 26 3 0 13 0 0 34 44 0 Woodland 3 31 2 1 7 0 0 53 40 1 West Hills 0 68 1 0 41 2 3 160 116 6 Totals: 39 1,690 36 10 719 32 17 2,320 2,827 65 BEDFORD County Precincts: 1-1 Wartrace 0 91 0 1 27 0 1 68 147 0 1-2 Bell Buckle 0 72 0 1 16 0 0 59 74 0 2-2 Longview 0 32 0 0 10 0 0 17 62 0 2-3 Airport -

Johnston (J. Bennett) Papers

Johnston (J. Bennett) Papers Mss. #4473 Inventory Compiled by Emily Robison & Wendy Rogers Louisiana and Lower Mississippi Valley Collections Special Collections, Hill Memorial Library Louisiana State University Libraries Baton Rouge, Louisiana Spring 2002 J. Bennett Johnston Papers Mss. 4473 1957-1997 LSU Libraries Special Collections Contents of Inventory Summary 3 Biographical/Historical Note 4 Scope and Content Note 5 Series, Sub-Series Description 6 Index Terms 16 Container List 19 Appendices 20 Use of manuscript materials. If you wish to examine items in the manuscript group, please fill out a call slip specifying the materials you wish to see. Consult the container list for location information needed on the call slip. Photocopying. Should you wish to request photocopies, please consult a staff member before segregating the items to be copied. The existing order and arrangement of unbound materials must be maintained. Publication. Readers assume full responsibility for compliance with laws regarding copyright, literary property rights, and libel. Permission to examine archival and manuscript materials does not constitute permission to publish. Any publication of such materials beyond the limits of fair use requires specific prior written permission. Requests for permission to publish should be addressed in writing to the Head of Public Services, Special Collections, LSU Libraries, Baton Rouge, LA, 70803-3300. When permission to publish is granted, two copies of the publication will be requested for the LLMVC. Proper acknowledgment of LLMVC materials must be made in any resulting writing or publications. The correct form of citation for this manuscript group is given on the summary page. Copies of scholarly publications based on research in the Louisiana and Lower Mississippi Valley Collections are welcomed. -

C:\TEMP\Copy of SCR65 Enrolled (Rev 7).Wpd

Regular Session, 2012 ENROLLED SENATE CONCURRENT RESOLUTION NO. 65 BY SENATORS ADLEY, ALARIO, ALLAIN, AMEDEE, APPEL, BROOME, BROWN, BUFFINGTON, CHABERT, CLAITOR, CORTEZ, CROWE, DONAHUE, DORSEY-COLOMB, ERDEY, GALLOT, GUILLORY, HEITMEIER, JOHNS, KOSTELKA, LAFLEUR, LONG, MARTINY, MILLS, MORRELL, MORRISH, MURRAY, NEVERS, PEACOCK, PERRY, PETERSON, RISER, GARY SMITH, JOHN SMITH, TARVER, THOMPSON, WALSWORTH, WARD AND WHITE AND REPRESENTATIVES ABRAMSON, ADAMS, ANDERS, ARMES, ARNOLD, BADON, BARRAS, BARROW, BERTHELOT, BILLIOT, STUART BISHOP, WESLEY BISHOP, BROADWATER, BROSSETT, BROWN, BURFORD, HENRY BURNS, TIM BURNS, BURRELL, CARMODY, CARTER, CHAMPAGNE, CHANEY, CONNICK, COX, CROMER, DANAHAY, DIXON, DOVE, EDWARDS, FANNIN, FOIL, FRANKLIN, GAINES, GAROFALO, GEYMANN, GISCLAIR, GREENE, GUILLORY, GUINN, HARRIS, HARRISON, HAVARD, HAZEL, HENRY, HENSGENS, HILL, HODGES, HOFFMANN, HOLLIS, HONORE, HOWARD, HUNTER, HUVAL, GIROD JACKSON, KATRINA JACKSON, JAMES, JEFFERSON, JOHNSON, JONES, KLECKLEY, LAMBERT, NANCY LANDRY, TERRY LANDRY, LEBAS, LEGER, LEOPOLD, LIGI, LOPINTO, LORUSSO, MACK, MILLER, MONTOUCET, MORENO, JAY MORRIS, JIM MORRIS, NORTON, ORTEGO, PEARSON, PIERRE, PONTI, POPE, PRICE, PUGH, PYLANT, REYNOLDS, RICHARD, RICHARDSON, RITCHIE, ROBIDEAUX, SCHEXNAYDER, SCHRODER, SEABAUGH, SHADOIN, SIMON, SMITH, ST. GERMAIN, TALBOT, THIBAUT, THIERRY, THOMPSON, WHITNEY, ALFRED WILLIAMS, PATRICK WILLIAMS AND WILLMOTT A CONCURRENT RESOLUTION To express the sincere condolences of the Legislature of Louisiana upon the passing of a legend and icon in Louisiana legislative -

TAPE #003 Page 1 of 10 F;1; ! G

') 1""~" TAPE #003 Page 1 of 10 f;1; _ ! G. DUPRE LITTON Tape 1 Mr. Litton graduated from the LSU Law School in 1942, having been president of Phi Delta phi Legal Fraternity, associate editor of Law Review, and the first LSU student named to the Order of the Coif. During a period of thirty-four years, Mr. Litton served in numerous important governmental capacities, including executive counsel to the governor, chairman of the ~ state board of tax appeals, first assistant attorney general, and legal advisor to the legislature. Q. Mr. Litton, your career in state government has closely involved you with the administrations of this state through several governors, dating back to the time of Huey Long. Would youqive us your recollections of the high points in these administrations? A. Thank you, Mrs. Pierce. My recollection of the governors of Louisiana dates back even prior to 1930, which was some 50 years ago. However, in 1930, I entered LSU, and at that time, Huey P. Long was governor. He had been elected in 1928. I recall that on a number of occasions, I played golf at the Westdale Country Club, which is now called Webb Memorial Country Club, I believe, and I saw Huey Long playing golf, accompanied, generally by some twelve to fifteen bodyguards who were on both sides of him, as he putted or drove. Enough has been written about Huey Long that it would probably be superfluous for us here at this time to go into any details concerning him. However, history will undoubtedly recall that Huey Long was one of the most powerful and one of the most brilliant governors in Louisiana history. -

Committee's Report

COMMITTEE’S REPORT (filed by committees that support or oppose one or more candidates and/or propositions and that are not candidate committees) 1. Full Name and Address of Political Committee OFFICE USE ONLY LOUISIANA REPUBLICAN PARTY Report Number: 15251 11440 N. Lake Sherwood Suite A Date Filed: 9/8/2008 Baton Rouge, LA 70816 Report Includes Schedules: Schedule A-1 2. Date of Primary 10/4/2008 Schedule A-2 Schedule A-3 This report covers from 12/18/2007 through 8/25/2008 Schedule B Schedule D 3. Type of Report: Schedule E-1 180th day prior to primary 40th day after general Schedule E-3 90th day prior to primary Annual (future election) X 30th day prior to primary Monthly 10th day prior to primary 10th day prior to general Amendment to prior report 4. All Committee Officers (including Chairperson, Treasurer, if any, and any other committee officers) a. Name b. Position c. Address ROGER F VILLERE JR. Chairperson 838 Aurora Ave. Metairie, LA 70005 DAN KYLE Treasurer 818 Woodleigh Dr Baton Rouge, LA 70810 5. Candidates or Propositions the Committee is Supporting or Opposing (use additional sheets if necessary) a. Name & Address of Candidate/Description of Proposition b. Office Sought c. Political Party d. Support/Oppose On attached sheet 6. Is the Committee supporting the entire ticket of a political party? X Yes No If “yes”, which party? Republican Party 7. a. Name of Person Preparing Report WILLIAM VANDERBROOK CPA b. Daytime Telephone 504-455-0762 8. WE HEREBY CERTIFY that the information contained in this report and the attached schedules is true and correct to the best of our knowledge , information and belief, and that no expenditures have been made nor contributions received that have not been reported herein, and that no information required to be reported by the Louisiana Campaign Finance Disclosure Act has been deliberately omitted . -

Intraparty in the US Congress.Pages

UC Berkeley UC Berkeley Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Intraparty Organization in the U.S. Congress Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/2cd17764 Author Bloch Rubin, Ruth Frances Publication Date 2014 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California ! ! ! ! Intraparty Organization in the U.S. Congress ! ! by! Ruth Frances !Bloch Rubin ! ! A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Political Science in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley ! Committee in charge: Professor Eric Schickler, Chair Professor Paul Pierson Professor Robert Van Houweling Professor Sean Farhang ! ! Fall 2014 ! Intraparty Organization in the U.S. Congress ! ! Copyright 2014 by Ruth Frances Bloch Rubin ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Abstract ! Intraparty Organization in the U.S. Congress by Ruth Frances Bloch Rubin Doctor of Philosophy in Political Science University of California, Berkeley Professor Eric Schickler, Chair The purpose of this dissertation is to supply a simple and synthetic theory to help us to understand the development and value of organized intraparty blocs. I will argue that lawmakers rely on these intraparty organizations to resolve several serious collective action and coordination problems that otherwise make it difficult for rank-and-file party members to successfully challenge their congressional leaders for control of policy outcomes. In the empirical chapters of this dissertation, I will show that intraparty organizations empower dissident lawmakers to resolve their collective action and coordination challenges by providing selective incentives to cooperative members, transforming public good policies into excludable accomplishments, and instituting rules and procedures to promote group decision-making. -

Suffolk University/7NEWS Likely N.H. Republican Presidential Primary Voters

Suffolk University/7NEWS Likely N.H. Republican Presidential Primary Voters POLL IS EMBARGOED UNTIL WEDNESDAY, MAY 4TH, AT 11:15 PM N= 400 100% Hillsborough ................................... 1 ( 1/ 91) 118 30% Rockingham ..................................... 2 92 23% North/West ..................................... 3 90 23% Central ........................................ 4 100 25% START Hello, my name is __________ and I am conducting a survey for 7NEWS/Suffolk University and I would like to get your opinions on some political questions. Would you be willing to spend five minutes answering some questions? N= 400 100% Continue ....................................... 1 ( 1/ 93) 400 100% RECORD GENDER N= 400 100% Male ........................................... 1 ( 1/ 94) 201 50% Female ......................................... 2 199 50% S2. How likely are you to vote in the Republican Presidential Primary in January of 2012? N= 400 100% Very likely .................................... 1 ( 1/ 95) 323 81% Somewhat likely ................................ 2 37 9% 50/50 .......................................... 3 40 10% Not very likely ................................ 4 0 0% Not at all likely .............................. 5 0 0% Other/Dk/RF .................................... 6 0 0% S3. Are you currently registered as a Democrat, Republican, Unenrolled/ Independent, something else or are you not registered to vote? N= 400 100% Democratic ..................................... 1 ( 1/ 98) 38 10% Republican .................................... -

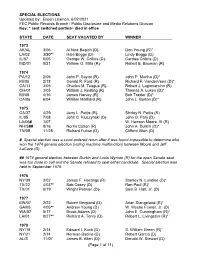

Special Election Dates

SPECIAL ELECTIONS Updated by: Eileen Leamon, 6/02/2021 FEC Public Records Branch / Public Disclosure and Media Relations Division Key: * seat switched parties/- died in office STATE DATE SEAT VACATED BY WINNER 1973 AK/AL 3/06 Al Nick Begich (D)- Don Young (R)* LA/02 3/20** Hale Boggs (D)- Lindy Boggs (D) IL/07 6/05 George W. Collins (D)- Cardiss Collins (D) MD/01 8/21 William O. Mills (R)- Robert E. Bauman (R) 1974 PA/12 2/05 John P. Saylor (R)- John P. Murtha (D)* MI/05 2/18 Gerald R. Ford (R) Richard F. VanderVeen (D)* CA/13 3/05 Charles M. Teague (R)- Robert J. Lagomarsino (R) OH/01 3/05 William J. Keating (R) Thomas A. Luken (D)* MI/08 4/16 James Harvey (R) Bob Traxler (D)* CA/06 6/04 William Mailliard (R) John L. Burton (D)* 1975 CA/37 4/29 Jerry L. Pettis (R)- Shirley N. Pettis (R) IL/05 7/08 John C. Kluczynski (D)- John G. Fary (D) LA/06# 1/07 W. Henson Moore, III (R) NH/S## 9/16 Norris Cotton (R) John A. Durkin (D)* TN/05 11/25 Richard Fulton (D) Clifford Allen (D) # Special election was a court-ordered rerun after it was found impossible to determine who won the 1974 general election (voting machine malfunction) between Moore and Jeff LaCaze (D). ## 1974 general election between Durkin and Louis Wyman (R) for the open Senate seat was too close to call and the Senate refused to seat either candidate. Special election was held in September 1975.