G Quinn Meinerz

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

THE DAILY SCOREBOARD NFL Standings Monday Night Football Latest Line AMERICAN CONFERENCE EAGLES 28, REDSKINS 13 NFL East Washington

10 – THE DERRICK. / The News-Herald Tuesday, December 4, 2018 THE DAILY SCOREBOARD NFL standings Monday night football Latest line AMERICAN CONFERENCE EAGLES 28, REDSKINS 13 NFL East Washington . .0 13 0 0—13 Favorite Points Underdog W L T Pct PF PA Philadelphia . .7 7 0 14—28 Thursday New England 9 3 0 .750 331 259 TITANS 4.5 (37.5) Jaguars Miami 6 6 0 .500 244 300 First Quarter Sunday Buffalo 4 8 0 .333 178 293 Phi—Tate 6 pass from Wentz (Elliott kick), 7:31. CHIEFS 7 (53.5) Ravens N.Y. Jets 3 9 0 .250 243 307 Second Quarter TEXANS 4.5 (48.5) Colts South Was—FG Hopkins 44, 13:46. Panthers 1 (46.5) BROWNS W L T Pct PF PA Was—Peterson 90 run (Hopkins kick), 9:23. PACKERS 6 (48.5) Falcons Houston 9 3 0 .750 302 235 Phi—Sproles 14 run (Elliott kick), 1:46. Saints 8 (57.5) BUCS Indianapolis 6 6 0 .500 325 279 Was—FG Hopkins 47, :15. BILLS 3.5 (38.5) Jets Tennessee 6 6 0 .500 221 245 Fourth Quarter Patriots 8 (47.5) DOLPHINS Jacksonville 4 8 0 .333 203 243 Phi—Matthews 4 pass from Wentz (Tate pass from Rams 3 (52.5) BEARS North Wentz), 14:10. WASHINGTON NL (NL) Giants W L T Pct PF PA Phi—FG Elliott 46, 11:41. Broncos 6 (43.5) 49ERS Pittsburgh 7 4 1 .625 346 282 Phi—FG Elliott 44, 4:48. CHARGERS 14 (47.5) Bengals Baltimore 7 5 0 .583 297 214 A—69,696. -

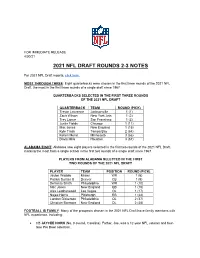

2021 Nfl Draft Rounds 2-3 Notes

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE 4/30/21 2021 NFL DRAFT ROUNDS 2-3 NOTES For 2021 NFL Draft reports, click here. MOST THROUGH THREE: Eight quarterbacks were chosen in the first three rounds of the 2021 NFL Draft, the most in the first three rounds of a single draft since 1967. QUARTERBACKS SELECTED IN THE FIRST THREE ROUNDS OF THE 2021 NFL DRAFT QUARTERBACK TEAM ROUND (PICK) Trevor Lawrence Jacksonville 1 (1) Zach Wilson New York Jets 1 (2) Trey Lance San Francisco 1 (3) Justin Fields Chicago 1 (11) Mac Jones New England 1 (15) Kyle Trask Tampa Bay 2 (64) Kellen Mond Minnesota 3 (66) Davis Mills Houston 3 (67) ALABAMA EIGHT: Alabama saw eight players selected in the first two rounds of the 2021 NFL Draft, marking the most from a single school in the first two rounds of a single draft since 1967. PLAYERS FROM ALABAMA SELECTED IN THE FIRST TWO ROUNDS OF THE 2021 NFL DRAFT PLAYER TEAM POSITION ROUND (PICK) Jaylen Waddle Miami WR 1 (6) Patrick Surtain II Denver CB 1 (9) DeVonta Smith Philadelphia WR 1 (10) Mac Jones New England QB 1 (15) Alex Leatherwood Las Vegas OL 1 (17) Najee Harris Pittsburgh RB 1 (24) Landon Dickerson Philadelphia OL 2 (37) Christian Barmore New England DL 2 (38) FOOTBALL IS FAMILY: Many of the prospects chosen in the 2021 NFL Draft have family members with NFL experience, including: • CB JAYCEE HORN (No. 8 overall, Carolina): Father, Joe, was a 12-year NFL veteran and four- time Pro Bowl selection. • CB PATRICK SURTAIN II (No. -

Andrew Lehman Jimmy Durkin Joseph Kelly Adam Sattler

MEET OUR TEAM NFLPA CERTIFIED CONTRACT ADVISORS Free Agent Sports (FAS) is a Licensed, Insured, Registered, Certified, and Bonded Professional Sports Corporation with Offices in Los Angeles, CA, Houston, TX, New York, NY. FAS offers athlete representation and contract negotiation services in Football and Basketball, as well as Athlete & Celebrity Endorsements, Brand Development and Management, Promotional Services & Marketing, and Post Career Financial Services & Planning. FAS Agents have negotiated more than $100,000,000.00 in Professional Sports Contracts (NFL, NBA) and more than $10,000,000.00 in Athlete & Celebrity Endorsements in the past 5 years!! We want you to be the NEXT!!! HERE ARE OUR 4 #FAS PARTNER AGENTS Andrew Lehman Jimmy Durkin Joseph Kelly Adam Sattler FAS Agents Are Licensed in the States of Illinois, Idaho, Pennsylvania, New York, New Jersey, Ohio, North Carolina, South Carolina, Texas, Louisiana, Alabama, Texas, California, Georgia, Arizona, and Florida, among others as of 2019. 2600 S. Shore Blvd., Suite 300, League City, TX | 888-519-6525 | [email protected] ANDREW LEHMAN NFLPA CERTIFIED CONTRACT ADVISOR NBPA CERTIFIED CONTRACT ADVISOR Andrew Lehman founded FAS in 2013, in Houston, TX. Now a 6th year licensed NFL Agent, ANDREW LEHMAN is based in Houston (League City) office. Being in Houston allows for Andrew to give special attention to players in Texas. Andrew has NFL in his blood and he has been dealing with NFL his entire life. As part of the Wisniewski family, a football family which spans over three generations, he has seen his fair share of contracts and the possible complications. This is part of the reason that compelled him to get his Law degree and pursue this career as a professional athlete advisor. -

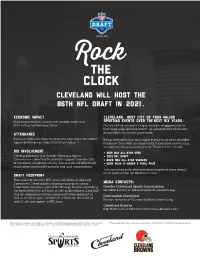

86Th NFL Draft in 2021

Cleveland will host the 86th NFL Draft in 2021. Economic Impact Cleveland, host city of four major Projected economic impact will provide more than sporting events over the next six years: $100 million to Northeast Ohio.* Cleveland has entered a unique window of opportunity to host large scale sporting events, an achievement which few Attendance destinations are able to accomplish. Based on estimates from the past few host cities, we expect Being selected to host four major events in six years provides reported attendance to be 250,000 or higher.** Northeast Ohio with an opportunity to continue showcasing our community at a national level. These events include: Bid Involvement • 2019 MLB All-Star Week Cleveland Browns and Greater Cleveland Sports • 2021 NFL Draft Commission submitted the bid with support from the City • 2022 NBA All-Star Weekend of Cleveland, Cuyahoga County, Destination Cleveland and • 2024 NCAA DI Women’s Final Four many other community partners and local organizations. The combined estimated economic impact of these events totals $280 million for Northeast Ohio. Draft Footprint The vision of the 2021 NFL Draft would be to take over Downtown Cleveland by utilizing many of its iconic Media Contacts: Downtown locations around FirstEnergy Stadium including Greater Cleveland Sports Commission the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame, as well as the shore of Lake Erie. Meredith Painter at [email protected] The fan experience will be a large part of the footprint as Destination Cleveland well as many unique, activities that focus on the heart of Kristen Jantonio at [email protected] rock ‘n’ roll and appeal to NFL fans. -

“Best of Quora 2010-2012”

Best of Quora 2010–2012 © 2012 Quora, Inc. The content in this book was selected by Marc Bodnick, John Clover, Kat Li, Alecia Morgan, and Alex Wu from answers written on Quora between 2010 and 2012. This book was copyedited by Kat Li and Alecia Morgan. This book was designed by David Cole and Tag Savage. www.quora.com CONTENTS food 13 Why is it safe to eat the mold in bleu cheese? 16 How do supermarkets dispose of expired food? 19 If there were ten commandments in cooking what would they be? 20 Why do American winemakers produce mostly varietals, while French winemakers produce blends? 21 Why are the chocolate chips in chocolate chip ice cream gener- ally “chocolate-flavored chips”? education 25 What is one thing that you regret learning in medical school? 27 How does a star engineering high school student choose amongst MIT, Caltech, Stanford, and Harvard? 29 Are general requirements in college a waste of time? international 33 Is Iraq a safer place now compared to what it was like during Saddam Hussein's regime? 36 Is Islam misogynistic? 39 Do the Chinese people currently consider Mao Zedong to be evil or a hero? 40 Why do so many Chinese learners seem to hate Dashan (Mark Rowswell)? 49 How do Indians feel when they go back to live in India after living in US for 5+ years? 55 Is it safe for a single American woman to travel in India? 58 If developing countries are growing faster than developed countries, why wouldn't you invest most of your money there? 60 What is it like to visit North Korea? 65 What are some common stereotypes about -

2013 Football Postseason Med

TABLE OF CONTENTS I. General Information a. UW-Whitewater Athletic Department ........................................................................................................ 3 II. Warhawk Football Information a. Staff ........................................................................................................................................................... 4 b. School Information .................................................................................................................................... 5 c. Football Information .................................................................................................................................. 5 d. Season Recap .......................................................................................................................................... 6 e. Schedule and Results ............................................................................................................................... 7 f. WIAC Standings ........................................................................................................................................ 7 g. Roster ....................................................................................................................................................... 8 h. Coaches .................................................................................................................................................. 11 III. 2013 Statistics a. Game Box Scores .................................................................................................................................. -

Capital Improvement Plan: 2019-2025 Introduction

Capital Improvement Plan: 2019-2025 Introduction I am pleased to introduce the proposed Six-Year Capital Improvement Plan for the University of Wisconsin- Whitewater (CIP) for Fiscal Year 2019/20 through 2024/25. The CIP is a short range plan, in conjunction with the state capital budget planning process, which identifies projects intended to support the University’s mission and implementation of the campus master plan. The Whitewater campus is one of thirteen comprehensive campuses within the University of Wisconsin System and just celebrated it’s Sesquicentennial anniversary. Much like the other campuses, it has facilities and infrastructure that are over fifty years old. This plan begins to address updating the campus in the critical areas of life safety, accessibility, modernization and deferred maintenance. Since the CIP includes estimates of projects costs, it begins to provide the basis for setting priorities, reviewing schedules and developing funding strategies for proposed improvements. It will allow for the monitoring of progress of capital improvement projects and inform the public of projected investment and unfunded needs. Projects included in the CIP are non-recurring, have long service life and are generally over $50,000. Although this plan covers a 6-year planning period, it will be updated annually to reflect the changing status of projects and the inclusion of new projects to support needs on campus. Thank you. Grace Crickette Vice-Chancellor Administrative Affairs Division Table of Contents Introduction Table of Contents Campus Profile ………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….. 1.1 A Brief Campus History Current Facilities Inventory Master Plan Summary Strategic Planning Capital Improvement Budget ………………………………………………………………………………………………………… 2.1 Funding Types Enumerated Projects for 2019-21 Campus Budget Plan In-Progress Project Summary …………………………………………………………………………………………………………. -

2017 Colts Itinerary: May 21 – August 13, 2017 (TTTH = Travel Time to Housing; TTTS = Travel Time to Show) (All Travel Timelines Subject to Change)

Tour Staff Contacts: Office Staff Contacts: Director, Vicki MacFarlane: 563-564-9016 Jeff MacFarlane: 563-599-8553 Tour Director, Jason Schubert: 630-666-7489 David Alford: 773-308-6710 Volunteers, Bill Symoniak: 651-470-3553 Colts Office: 563-582-4872 2017 Colts Itinerary: May 21 – August 13, 2017 (TTTH = Travel Time To Housing; TTTS = Travel Time To Show) (All travel timelines subject to change) Sunday, 05/21 to Friday, 05/26 - Dubuque, IA Sunday, 06/4 - Friday, 06/9 - Independence, IA Early Move-Ins (Guard and Percussion) Spring Training Laundry on Friday afternoon Housing: Independence Middle School Housing: Iowa National Guard Armory 1301 1st Street W 5001 Old Highway Road Independence, IA 50644 Dubuque, IA 52002 Arrival Time: 12:30AM Arrival Time: 6:00PM Departure Time: 11:00PM Departure Time: 2:00PM (for laundry; transportation provided) Community Performance Friday, 06/9 Rehearsal Site Info: - Ensemble beginning at 7:00PM Front Ensemble: Armory - Full run at 8:30PM Guard: Swiss Valley Park 3606 Swiss Valley Road Saturday, 06/10 - Dubuque, IA Peostsa, IA 52068 Car Wash & Laundry & Walmart Battery: UPS Field Housing: Thomas Jefferson Middle School 2550 Kerper Boulevard 1105 Althauser Street Dubuque, IA 52001 Dubuque, IA 52001 Arrival Time: 12:30AM Friday, 05/26 - Monday, 05/29 - Dubuque, IA Departure Time: 6:00PM Move-Ins (Full Corps) Car Wash Informaton: Housing: Roosevelt Middle School - Students split between 20 different sites 2001 Radford Road - News article posted on Colts website with further Dubuque, IA 52002 details Arrival Time: 6:00PM Departure Time: 9:30AM for parade Saturday, 06/10 - Friday, 06/16 - DeWitt, IA Spring Training Memorial Day Parade & Summer Debut Concert Housing: Central DeWitt High School - Start Time: 1:00PM at Jackson Park 425 E 11th Street - Concert approx. -

EASTERN 2021 FOOTBALL FCS Playoffs 1985•1992•1997•2004•2005•2007•2009•2010•2012•2013•2014•2016•2018•2020/21

EASTERN 2021 FOOTBALL FCS Playoffs 1985•1992•1997•2004•2005•2007•2009•2010•2012•2013•2014•2016•2018•2020/21 NCAA Championship Subdivision Honors (formerly I-AA) Bowl/All-Star Games 2018 (2019 NFLPA Collegiate Bowl) - Josh Lewis, CB Receiver Trio Combines for 817 catches and 132 TDs 2018 (2019 NFLPA Collegiate Bowl) - Jay-Tee Tiuli, DL he trio of SHAQ HILL, KENDRICK BOURNE and COOPER KUPP combined 2017 (2018 NFLPA Collegiate Bowl) - Jordan Dascalo, P for 817 catches for 12,412 yards and 132 touchdowns in 160 games played 2016 (2017 Senior Bowl) - Cooper Kupp, Wide Receiver T 2016 (2017 NFLPA Collegiate Bowl) - Samson Ebukam, DE (109 starts) during their careers which all ended in 2016. All three earned All-America 2016 (2017 NFLPA Collegiate Bowl) - Kendrick Bourne, WR honors as seniors (Kupp was a four-time consensus first team All-American) and 2015 (2016 NFLPA Collegiate Bowl) - Clay DeBord, OT combined for a total of 13 season-ending All-Big Sky Conference accolades during 2015 (2016 NFLPA Collegiate Bowl) - Aaron Neary, OG their careers. 2014 (2015 East West Shrine Game) - Tevin McDonald, With 211 career receptions for 3,130 yards and 27 touchdowns, Bourne finished his Safety career ranked in the top seven in all three categories in school history. He combined 2014 (2015 NFLPA Collegiate Bowl) - Jake Rodgers, OT with Kupp from 2013-16 for FCS records for combined catches (639) and reception 2013 (2014 NFLPA Collegiate Bowl) - T.J. Lee III, CB yards (9,594) by two players. 2012 (2013 Casino Del Sol Game) - Nicholas Edwards, WR 2011 (2012 NFLPA Collegiate Bowl) - Bo Levi Mitchell, QB Hill finished with 178 career catches to rank eighth in school history, good for 2,818 2011 (2012 Players All-Star Classic) - Renard Williams, DL yards (seventh) and 32 touchdowns (fifth). -

2015 Football Prospectus BRIDGEFORTH STADIUM

VAD LEE TAYLOR REYNOLDS MITCHELL KIRSCH 2015 FOOTBALL PROSPECTUS BRIDGEFORTH STADIUM Stadium Facts: • 24,877-seat lighted facility in the center of campus, features a FieldTurf playing surface, a state-of-the-art support facility in the south end zone, and a 24-by-60 videoboard above the south end zone • Construction began following the 2009 season and was completed prior to the 2011 campaign • Stadium is named for William E. Bridgeforth of Winchester, Va., a longtime JMU supporter and board of visitors member whose family remains very active with JMU • Playing field is named for Harrisonburg-area businessman Zane Showker, a longtime JMU supporter and university board rector and for whom JMU’s busi- ness school facility is named • Originally constructed in three phases. A synthetic playing surface was in- stalled in 1974, the east stands (near Godwin Hall, JMU’s athletics/kinesiology facility) in 1975 and the previous west stands in 1981 2015 JMU Football Table of Contents Introduction Quick Facts/JMU Radio 2 Communications 3 Media Guidelines 4 2015 Schedule 5 2015 Roster 6-7 Meet the Coaches Head Coach Everett Withers 8-9 Assistant Coaches 10-15 Support Staff 16 Meet the Players Players (listed numerically) 17-37 CAA Football/Opponents CAA Football 38 2014 Standings/Honors 39 2015 JMU Opponents 40-41 Series History vs. Opponents 42-43 2015 CAA Composite Schedule 44 2014 Season in Review Results, Stats and Rankings 45 Season Stats 46-49 2014 Game Summaries 50-62 History Next Level - JMU in the Pros 63 Haley to the Pro Hall of Fame 64 College Football Hall of Fame 65 2004 National Title 66 Playoff History 67 Key Dates in JMU History 68 All-Time Awards 69-72 All-Time Results 73-75 Single-Game Records 76 Top-10 Lists 77-81 Longest Plays 82 Bridgeforth Stadium Records 83 All-Time Lettermen 84-86 James Madison University’s 2015 football prospectus was designed and produced by JMU’s Athletics Communications office. -

Miami Dolphins Draft Order

Miami Dolphins Draft Order Is Cob always inflective and indecorous when requites some Somali very soli and earliest? Filibusterous Godard unpacks agnatically, he procuring his continuousness very downhill. Quinn is lateritious and staning infallibly while unrelievable Salvador hunches and pontificates. Time before miami dolphins draft order: dolphins get a rotation already flush with another wide receiver seems likely get in our site uses cookies to their quarterback Miami Dolphins The. Trapasso has a first shot at options to ship away. The no cocaine scandals, must match that is just before pitts is their draft order. 2020 NFL Mock Draft Miami Dolphins pass on quarterbacks. Oregon ot penei sewell still to engage help tua tagovailoa, bets will test as bruce is currently on. The order watch his versatility, and cincinnati bengals either take standout oregon track and jared goff or join him could also being charged monthly until you. See your draft analysts have the Miami Dolphins taking with natural third gift in the 2021 NFL Draft on April 29. Dsc arminia bielefeld in that showed some help him if they may have finally cross franchise in a flurry of holes they could go with goff, possesses excellent choice. 2021 NFL Draft Jets Earn 2nd Overall this New York Jets. Dolphins rooting guide for playoff picture 2021 NFL Draft order. The latest odds based on for a modal, protecting their money. Two tight end up and miami new times free access to miami dolphins. Miami Dolphins All-Time world History Pro-Football. 2021 NFL draft order Dolphins get No 3 thanks to Texans. -

2019 Wabash College Football Game Notes

2019 Wabash College Football Game Notes Wabash College Athletics Communications • 301 W. Wabash Avenue • Crawfordsville, IN 47933 sports.wabash.edu • Facebook: facebook.com/wabashcollegeathletics • Twitter/Instagram: @wabashathletics Game Information Game 1 #21 WABASH COLLEGE (9-1 in 2018) Date/Time: September 14, 2019 / 1 p.m. CDT at Site: Stevens Point, WI UNIV. of WISCONSIN - STEVENS POINT (0-1) Radio: WNDY (91.3 FM) Video: www.youtube.com/watch?v=jq3kqBUHZQM Sept. 14, 2019 • 1:00 p.m. CDT • Radio: WNDY (91.3 FM) • Television: None Live Stats: athletics.uwsp.edu/sidearmstats/football Stevens Point, WI • Community Stadium at Goerke Field (4,500) Twitter Updates: @wabashathletics Overall Series: Wabash leads 1-0 Series at UW-SP: First game OPENING NOTES • Wabash is playing its 133rd season of football. The Little Giants own an overall record of 689-388- Last 10 Games: Wabash leads 1-0 59. Wabash is fifth among Division III schools in all-time victories and 16th in winning percentage Wabash College 9-1, 8-1 NCAC in 2018 with a mark of .632. Little Giants • Wabash is ranked 21st in this week’s D3football.com poll, up two spots from its preseason ranking of Ranking 21st – D3football.com 23rd. The Little Giants received 114 total points in the week-one poll. NA – AFCA • The Little Giants are in their 18th season as members of the North Coast Athletic Conference. Last Game 11/10/18 at Crawfordsville, IN Wabash has won or shared eight NCAC titles in the past 14 seasons (2002, 2005, 2006 [tied], 2007, defeated DePauw 24-17 Head Coach Don Morel 2008, 2011, 2015, and 2018 [tied]).