Tailoring Engagement with Urban Nature for University of Sheffield Students’ Wellbeing

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sheffield Parks and Open Spaces Survey 2015-16

SHEFFIELD PARKS AND OPEN SPACES SURVEY 2015-16 Park/ Open space Surveyor(s)/year Park/ Open space Surveyor(s)/ year (postcode/ grid ref) (postcode/ grid ref) Abbeyfield Park C. Measures Little Matlock Wood, Pete Garrity (S4 / 358894) Loxley Valley (S6/ 310894) Beeley Wood H. Hipperson Little Roe Woods (357898) E. Chafer Bingham Park R. Hill Longley Park (S5/ 358914) Bolehills Rec’n Ground Bruce Bendell Meersbrook Allotments Dave Williams Walkley (S6 / 328883) (S8 / 360842) Botanical Gardens Ken Mapley Meersbrook Park B. Carr Bowden Housteads R. Twigg Middlewood Hospital Anita and Keith Wood site (S6 / 320915) Wall Burngreave Cemetery Liz Wade Millhouses Park P. Pearsall (S4 / 360893) Chancet Wood Morley St Allotments, (S8 / 342822) Walkley Bank (S6/ 328892) Concord Park (S5) Norfolk Park (S2 / 367860) Tessa Pirnie Crabtree Pond Parkbank Wood (S8) / Mike Snook (S5 / 362899) Beauchief Golf Course Crookes Valley Park D. Wood Ponderosa (S10 / 341877) Felix Bird Earl Marshall Rec C. Measures Rivelin Valley N. Porter Ground (S4 / 365898) Ecclesall Woods PLB/ J. Reilly/ Roe Woods, P. Medforth/ Burngreave (S5 / 357903) Endcliffe Park C. Stack Rollestone Woods, P. Ridsdale Gleadless (S14 / 372834) Firth Park (S5/ 368910) Shirecliffe (S5 / 345903) Andy Deighton General Cemetery – A & J Roberts The Roughs – High Storrs/ Roger Kay Sharrow Hangingwater (S11/315851) Gleadless Valley (S14 / P. Ridsdale Tinsley Golf Course (S9 / Bob Croxton 363838) 405880) Graves Park M. Fenner Tyzack’s Dam / Beauchief P. Pearsall Gardens Hagg Lane Allotments C. Kelly Wardsend Cemetery, Mavis and John (S10 / 318877) Hillsborough (S6 / 341904) Kay High Hazels (S9/ 400877) Weston Park (S10/ 340874) Louie Rombaut Hillsborough Park E. -

Yourthe Magazine for Alumni and Friends 2011 – 2012

UNIVERSITY yourTHE MAGAZINE FOR ALUMNI AND FRIENDS 2011 – 2012 A celebration of excellence HIGHLIGHTS FROM THE ROYAL VISIT HM The Queen is seen here wearing a pair of virtual reality glasses during the ground-breaking ceremony at the University’s Advanced Manufacturing Research Centre page 6 Alumni merchandise Joe Scarborough prints University tie In 2005, to celebrate the University’s Centenary, Sheffield artist Joe Scarborough In 100% silk with multiple (Hon LittD 2008) painted Our University, generously funded by the Sheffield University University shields Association of former students. Sales of the limited edition signed prints raised over Price: £18 (incl VAT) £18,000 for undergraduate scholarships. The University has now commissioned Joe Delivery: £1.00 UK; to paint a sister work entitled Our Students’ Journey which hangs in the Students’ Union. £1.30 Europe; £18 It depicts all aspects of student life including the RAG boat race and parade, student £1.70 rest of world (INCL VAT) officer elections and summer activities in Weston Park. We are delighted to be offering 500 limited edition signed prints. All proceeds will again provide scholarships for gifted students in need of financial support, £40 and to help the University’s Alumni Foundation which distributes grants (INCL VAT) to student clubs and societies. Our Students’ Journey Limited edition signed prints, measuring 19” x 17”, are unframed and packed in protective cardboard tubes and priced at £40.00 (incl VAT). Our University A very limited number of these prints (unsigned) are still available. Measuring 19” x 17”, they are unframed and packed in protective cardboard tubes and priced at £15.00 (incl VAT). -

Boats, Trams & Elephants

Development & Alumni Relations Office. Boats, Trams & Elephants. Experiences of University life 1935–65 Distributing copies of Twikker, the Rag magazine, in 1955. The procession down West Street is led by Frank Falkingham, Shirley Wray and Gerry Fishbone, with Gordon Kember (editor) on the first elephant, and Alan Cox, President of the Students’ Union, behind. The elephants were supplied by Chipperfield’s Circus. Photo from Dr Alan Cox (MB ChB Medicine 1958, MD Medicine 1962) Starting out When I started at Sheffield in 1944 the undergraduates numbered about 750, almost all male in both the physical Thank you and applied sciences and the medical faculty. Then there This magazine is the result of a request for memories of was a large intake of ex-service men in 1946 so the numbers student life from pre-1965 alumni of the University of Sheffield. shot up. In addition the University provided three-month The response has been fantastic and I wish to thank everyone courses for American service men. With all these older men, who has taken the time to commit their recollections to paper we youngsters saw precious little of what female students and sent in photos and other memorabilia. there were available socially. This dire situation at least The magazine includes just a fraction of the material supplied; encouraged serious study and we were able to write home I apologise if your contribution doesn’t appear here, and we that we were keeping our noses to The Grindstone, that will endeavour to include other examples in future alumni being the name of a local pub, though few of us had much publications. -

Central Community Assembly Area Areas and Sites

Transformation and Sustainability SHEFFIELD LOCAL PLAN (formerly Sheffield Development Framework) CITY POLICIES AND SITES DOCUMENT CENTRAL COMMUNITY ASSEMBLY AREA AREAS AND SITES BACKGROUND REPORT Development Services Sheffield City Council Howden House 1 Union Street SHEFFIELD S1 2SH June 2013 CONTENTS Chapter Page 1. Introduction 1 Part 1: City Centre 2. Policy Areas in the City Centre 5 3. Allocated Sites in the City Centre 65 Part 2: Sheaf Valley and Neighbouring Areas 4. Policy Areas in Sheaf Valley and Neighbouring Areas 133 5. Allocated Sites in Sheaf Valley and Neighbouring Areas 175 Part 3: South and West Urban Area 6. Policy Areas in the South and West Urban Area 177 7. Allocated Sites in the South and West Urban Area 227 Part 4: Upper Don Valley 8. Policy Areas 239 9. Allocated Sites in Upper Don Valley 273 List of Tables Page 1 Policy Background Reports 3 2 Potential Capacity of Retail Warehouse Allocations 108 List of Figures Page 1 Consolidated Central and Primary Shopping Areas 8 2 Illustrative Block Plan for The Moor 9 3 Current Street Level Uses in the Cultural Hub 15 4 Priority Office Areas 21 5 City Centre Business Areas 28 6 City Centre Neighbourhoods 46 7 City Centre Open Space 57 8 Bramall Lane/ John Street 139 1. INTRODUCTION The Context 1.1 This report provides evidence to support the published policies for the City Policies and Sites document of the Sheffield Local Plan. 1.2 The Sheffield Local Plan is the new name, as used by the Government, for what was known as the Sheffield Development Framework. -

New Open Space Section 106 Agreements Need to Be Considered By

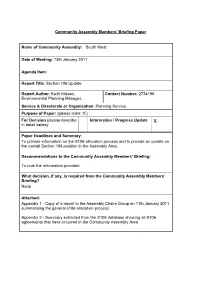

Community Assembly Members’ Briefing Paper Name of Community Assembly: South West Date of Meeting: 13th January 2011 Agenda Item: Report Title: Section 106 Update Report Author: Keith Missen, Contact Number: 2734196 Environmental Planning Manager. Service & Directorate or Organisation: Planning Service, Purpose of Paper: (please mark ‘X’) For Decision (please describe Information / Progress Update X in detail below) Paper Headlines and Summary: To provide information on the S106 allocation process and to provide an update on the overall Section 106 position in the Assembly Area. Recommendations to the Community Assembly Members’ Briefing: To note the information provided What decision, if any, is required from the Community Assembly Members’ Briefing? None Attached: Appendix 1 - Copy of a report to the Assembly Chairs Group on 11th January 2011 summarising the general s106 allocation process. Appendix 2 - Summary extracted from the S106 database showing all S106 agreements that have occurred in the Community Assembly Area 1.0 PURPOSE OF THIS REPORT 1.1 To advise Members of the process discussed with the Chair for allocating open space Section 106 agreements to projects. 1.2 To provide an update on the general Section 106 position for the Assembly Area. 1.3 To provide members with further information in two appendices, covering the Section 106 allocation process and providing a summary of all agreements extracted from the Section 106 monitoring database. 1.4 To answer any questions that members may have on the Section 106 process. 2.0 PROCESS DISCUSSED FOR ALLOCATING S106 AGREEMENTS TO PROJECTS. 2.1 New open space Section 106 agreements need to be considered by Community Assemblies at least once, and preferably twice, each year so that they can be allocated to project sites. -

Consolidated Burial Records

Consolidated Burial Records - Ecclesfield Cemetery - Churchyard Section Ecclesfield Cemetery, Priory Road, Ecclesfield, Sheffield, South Yorkshire, S35 9XY Related Files: Plan Showing Churchyard Burial Sections.jpg and Plan Showing Churchyard Burial Sections.pdf ©Copyright St Mary's Church - Ecclesfield and Others User Notes: This Spreadsheet contains 6320 Records covering the Old Burial Ground, Burial Ground South Pts 1 & 2 and Burial Ground North Pts 1 & 2 The records are sorted by SURNAME - then by PLOT NO and then by FIRST NAME to ensure all family burials are grouped together The LINE (CELL) background colours YELLOW, WHITE, PINK or BLUE indicate the location area on the corresponding plan In the AGE column suffix: Inf = Infant d = days w = weeks m = months age at time of death The ABODE column indicates the domicile (if known) at time of death Updated 24th June 2018 to correct minor date issue in BGN 1&2 - Final Document runs to 116 pages INDEX the index column has been left empty for your own reference to be added INDEX SURNAME FIRST NAME AGE BURIAL DATE PLOT NO AREA ABODE ABRAHAM Elijah 51 21/02/1907 26 South Part 2 Grenoside Workhouse ADAMS Fanny 76 13/01/1932 306 O/B Part 3 45 Johnson Lane/Ecclesfield ADAMS Jonathan 80 04/12/1937 306 O/B Part 3 5 Millhouse Rd/Crookes/Sheffield ADAMS Charles Ephraime Wood 6m 10/03/1899 209 South Part 2 8 Bardwell Rd/Wincobank ADAMS Hannah Holmes 57 23/01/1899 209 South Part 2 8 Bardwell Rd/Wincobank ADCOCK Alice 7 29/05/1898 107 South Part 2 Ecclesfield ADCOCK Mary 76 04/03/1929 107 South Part -

Candidates Summary

SHEFFIELD CITY COUNCIL CANDIDATES SUMMARY CITY COUNCIL ELECTIONS ± 6 MAY 2010 Area Candidates Party Description Address Arbourthorne Ward Jennyfer BARNARD Green Party 259 Myrtle Road, Sheffield, S2 3HH, Jayne DORE Liberal Democrats 29 Milton Road, Sheffield, S7 1HP, Jack SCOTT The Labour Party 23 Tylney Road, Sheffield, S2 2RX, Candidate Peter SMITH The Conservative Party 91 Fraser Road, Sheffield, S8 0JH, Candidate Joanne THOMAS British National Party 5 Longley Close, Sheffield, S5 7JB, Beauchief & Greenhill Ajaz AHMED The Labour Party 24 Wake Road, Sheffield, S7 1HG, Ward Candidate John Winston BEATSON British National Party 44 Lupton Walk, Low Edges, Sheffield, S8 7NR Michelle GRANT The Conservative Party 38 Norton Lees Lane, Sheffield, S8 Candidate 9BD, Christina HESPE Green Party 43 Bocking Lane, Beauchief, Sheffield, S8 7BG Clive Anthony SKELTON Liberal Democrats 48 Parkhead Road, Sheffield, S11 9RB, Beighton Ward Andrew Julian Green Party 145 Upper Valley Road, Sheffield, BRANDRAM S8 9HD, Shirley Diane CLAYTON The Conservative Party 4 Broadlands Rise, Owlthorpe, Candidate Sheffield, S20 6RT Robbie COWBURY Liberal Democrats 53 Holberry Gardens, Sheffield, S10 2FR, Matthew Joseph British National Party Flat 1, 125 Wulfric Road, Manor, GOULDSBROUGH Sheffield, S2 1DZ Wayne Anthony UK Independence Party Flat 3, 246 Duke Street, Sheffield, HARLING (UK I P) S2 5QQ Helen MIRFIN- The Labour Party Appledore, 28 Mosborough Hall BOUKOURIS Candidate Drive, Halfway Sheffield, S20 4UA Birley Ward Graham CHEETHAM UK Independence Party 22 East -

SHEFFIELD CITY COUNCIL Central Community Assembly Report

SHEFFIELD CITY COUNCIL Central Community Assembly 8 Report Report of: Report of the Community Assembly Manager and the Director of Parks and Countryside ___________________________________________________________ Date: March 24 th 2011 ___________________________________________________________ Subject: Central Assembly Parks Report ___________________________________________________________ Author of Report: Mary Bagley. Director of Parks and Countryside David Aspinall – Community Assembly Manager Stuart Turner, Acting Parks Tasking Officer and Programme Manager, Parks and Countryside Service (0114 273 6956) __________________________________________________ Summary: This report provides further details on three areas of the Parks and Countryside service: 1. A brief outline of the potential budget implications for Parks and Countryside Services given the 16% budget cuts for 2011-12 and future service shape 2. An update on the devolution pilot project within the Central Community Assembly 3. An update on Parks and Countryside priorities and Voice and Choice within the Central Community Assembly _______________________________________________________ Reasons for Recommendations: • It is important that the Parks and Countryside Service and Community Assembly work closely together in order to maximise the benefits from the resources available by providing information and guidance on technical, operational and financial options and opportunities 1 • The provision, quality and maintenance of green spaces throughout the Central area can often be the basis of passionate support and/or complaints from local people. ‘A City of Opportunity’, Sheffield’s Corporate Plan 2010-13 identifies the main priorities for the City and its residents. “Improving Parks and Open spaces” is a key priority area within this Plan and the City has recently agreed a Green and Open Spaces Strategy 2010-2030 to move this agenda forward and raise the standard of green spaces throughout the City. -

A Pocket Guide to Our Friendly, Hilly City Coffee and Cocktails in Old Cutlery Works

PEAK DISTRICT A pocket guide to our friendly, hilly city Coffee and cocktails in old cutlery works. Art exhibitions in transformed factories. A lot Vintage treasures line the streets in one corner of the city; in another, an inviting, international array of restaurants extends for a mile. The happens biggest – and best – theatre complex outside of London is just down the road from one of within Europe’s biggest indie cinemas. Festivals of art, film, music, the great outdoors and literature bring the city to life, whatever the season. Sheffield’s Get to know Sheffield: the friendly, hilly, multicultural city that around 564,000 people seven hills. – including 58,000 students – love to call home. This booklet is written by Our Favourite Places in collaboration with the University of Sheffield. Our Favourite Places is an independent guide to the creative and unconventionally beautiful city of Sheffield, here they have highlighted some of their best loved places in the region. www.ourfaveplaces.co.uk 4 Botanical gardens University – Firth Court The Peak District University – Arts Tower Sectiontitle University – Information Commons London Road Devonshire quarter City centre Peace Gardens Railway station 5 Our city – how to get here The big northern cities of Leeds, Manchester and York are less than an hour away by train. Within two Where is hours, you can make it to Liverpool to the west, Newcastle to the Sheffield? north, and Hull to the east. Getting to Sheffield: Getting around Sheffield: By train By tram Trains connect Sheffield directly to The Supertram is the handiest way most major British cities, as well to get around the city, with stops as outlying suburbs, Meadowhall at the University, the station, the shopping centre, and the nearby Cathedral, and more. -

BBEST Design Guide

BBEST DESIGN GUIDE V10 March 2021 CONSULTANT/CLIENT INFORMATION Project BBEST Design Guide Client BBEST Title of Document BBEST DESIGN GUIDE File Origin rtu2017-ID-005 CONTENTS BBEST Design Guide 1. Introduction Pg. 4 2. Characteristics of BBEST Area Pg. 6 Conservation Areas Listed Buildings Variety of scales and building types and routes 3. Key Principles Pg. 12 What is important Maintaining key views Sites of Particular Signifi cance to the Community 4. Character Area Appraisals Pg. 24 Introduction Crookes Valley Pg. 26 Hospital Quarter Pg. 32 Residential South East Pg. 38 Residential North East Pg. 44 Retail Centre Pg. 50 Residential North West Pg. 58 Residential South West Pg. 64 Endcliff e Pg. 70 BBEST Design Guide 3 1. INTRODUCTION The BBEST Design Guide sits alongside the BBEST Neighbourhood Plan as a companion document. The character of the whole area is distinctive and attractive. This document seeks to identify the chacteristics that make the area special with a view to ensuring that new development can be brought forward in a manner that respects this unique character, repairs past mistakes or damage and takes opportunities to deliver improvements. The document provides a balance of guidelines and policy to inform development. The document is split into 3 main sections - Characteristics of the area - Key Principles - covering design principles relevant to the whole area. - Character Areas - The BBEST area has been split into 8 character areas, describing the specifi c issues and opportunities unique to particular areas. The BBEST area covers a signifi cant zone to the west of Sheffi eld City Centre. -

King Teds 2005 Book

King Ted's A biography of King Edward VII School Sheffield 1905-2005 By John Cornwell Published by King Edward VII School Glossop Road Sheffield, S10 2PW KES E-Mail address is: [email protected] First Edition Published October 2005 Copyright © John Calvert Cornwell 2005 All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, by photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. All views and comments printed in this book are those of the author and should not be attributed to the publisher. ISBN Number 0-9526484-1-5 Printed by DS Print, Design & Publishing 286 South Road Walkley Sheffield S6 3TE Tel: 0114 2854050 Email: [email protected] Website: www.dspad.co.uk The cover design is by Andrew Holmes, a KES Y13 Sixth Form student in 2005. The title page from a watercolour by Ben Marston (KES 1984-90), painted in 1993. CONTENTS FOREWORD...................................................................................................................7 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS.............................................................................................8 TOM SMITH’S LEGACY 1604-1825...........................................................................13 THE TAKEOVER 1825-1905.......................................................................................22 WESLEY COLLEGE - A PALACE FOR THE CHILDREN OF THE KING OF KINGS....36 MICHAEL SADLER’S MARRIAGE PROPOSAL 1903 - 1905...................................58 -

Appendix 3 Byelaws in Respect of Pleasure Grounds

Appendix 3 Byelaws in respect of Pleasure Grounds CITY OF SHEFFIELD BYELAWS made by the Lord Mayor, Alderman and Citizens of the City of Sheffield, acting by the Council, with respect to PLEASURE GROUNDS SYDNEY HILTON Town Clerk City of Sheffield At a QUARTERLY MEETING of the COUNCIL of the CITY of SHEFFIELD, held in the COUNCIL CHAMBER in the TOWN HALL in SHEFFIELD aforesaid, on the Second day of February at two o'clock in the afternoon, pursuant to Notice duly given and Summonses duly served: - WE, the Lord Mayor, Aldermen and Citizens of the City of Sheffield, being now duly met and assembled together, do hereby, under and by virtue and in pursuance of the powers to us for that purpose given by the Public Health Act, 1875, and the Open Spaces Act, 1906, make, order and ordain the following byelaws: - 1. Throughout these byelaws the expression “the Council” means the Lord Mayor, Aldermen and Citizens of the City of Sheffield, the expression “the pleasure ground” means, except where inconsistent with the context, each of the pleasure grounds known as Abbeyfield Park, Arbourthorne Playing Fields, Attercliffe Recreation Ground, Beauchief Abbey Grounds, Beauchief Dam, Beauchief Drive Playground, Beaver Hill Recreation Ground, Beckett Avenue Children's Playground (Greenhill), Beighton Road Open Space (Hackenthorpe), Bingham Park, Blacka Moor, Blackbrook Wood, Bocking Lane Open Space, Bole Hill Recreation Ground, Botanical Gardens, Bowden Housteads Wood, Bradway Recreation Ground, Bright Street Playground, Brightside Recreation Ground, Brincliffe