16 March 2020 PRE-TRIAL CHAMBER I Before

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Steps to Statehood Timeline

STEPS TO STATEHOOD TIMELINE Tags: History, Leadership, Balfour, Resources 1896: Theodor Herzl's publication of Der Judenstaat ("The Jewish State") is widely considered the foundational event of modern Zionism. 1917: The British government adopted the Zionist goal with the Balfour Declaration which views with favor the creation of "a national home for the Jewish people." / Balfour Declaration Feb. 1920: Winston Churchill: "there should be created in our own lifetime by the banks of the Jordan a Jewish State." Apr. 1920: The governments of Britain, France, Italy, and Japan endorsed the British mandate for Palestine and also the Balfour Declaration at the San Remo conference: The Mandatory will be responsible for putting into effect the declaration originally made on November 8, 1917, by the British Government, and adopted by the other Allied Powers, in favour of the establishment in Palestine of a national home for the Jewish people. July 1922: The League of Nations further confirmed the British Mandate and the Balfour Declaration. 1937: Lloyd George, British prime minister when the Balfour Declaration was issued, clarified that its purpose was the establishment of a Jewish state: it was contemplated that, when the time arrived for according representative institutions to Palestine, / if the Jews had meanwhile responded to the opportunities afforded them ... by the idea of a national home, and had become a definite majority of the inhabitants, then Palestine would thus become a Jewish commonwealth. July 1937: The Peel Commission: 1. "if the experiment of establishing a Jewish National Home succeeded and a sufficient number of Jews went to Palestine, the National Home might develop in course of time into a Jewish State." 2. -

Saint Mary's University Fall Convocation Sunday, 29 October

Saint Mary's University Fall Convocation Sunday, 29 October 2006 O CANADA O Canada! Our home and native land! True patriot love in all thy son's command. With glowing hearts we see thee rise, The True North strong and free! From far and wide, O Canada, We stand on guard for thee. God keep our land, glorious and free! O Canada, we stand on guard for thee, O Canada, we stand on guard for thee. Convocation is a joyous yet solemn event, bound by traditions which have evolved over centuries. It is a continuum with a formal beginning and an end. By being present here today, you have indicated your interest in being part of this academic tradition. Graduating students and their guests are therefore expected to remain in their seats until this formal ceremony has been completed in its entirety - the Chancellor of the University has officially closed Convocation and the stage party and graduates have recessed. Order of Academic Procession Marshal of Convocation Graduates Faculty Guests Board of Governors Deans of Faculties President, Deans, and Faculty Emeriti/ae Recipients of Honorary Degrees Vice-President, Academic and Research President Chancellor The audience is requested to stand when the Academic Procession arrives, to remain standing until the close of the Prayer of Invocation; and at the close of Convocation, to remain standing until all the Academic Procession has recessed. Please note that names of graduates listed in this program are subject to revision. Order of Proceedings Processional Welcome O Canada Heather Fitzpatrick, B.P.R. Introduction of Special Guests Invocation Father George Leach, S.J., B.A., M.Ed., M.A.Th., D.Min., Valedictory Address Chenara Murray Awards (a) President's Award for Excellence in Research E. -

Masada National Park Sources Jews Brought Water to the Troops, Apparently from En Gedi, As Well As Food

Welcome to The History of Masada the mountain. The legion, consisting of 8,000 troops among which were night, on the 15th of Nissan, the first day of Passover. ENGLISH auxiliary forces, built eight camps around the base, a siege wall, and a ramp The fall of Masada was the final act in the Roman conquest of Judea. A made of earth and wooden supports on a natural slope to the west. Captive Roman auxiliary unit remained at the site until the beginning of the second Masada National Park Sources Jews brought water to the troops, apparently from En Gedi, as well as food. century CE. The story of Masada was recorded by Josephus Flavius, who was the After a siege that lasted a few months, the Romans brought a tower with a commander of the Galilee during the Great Revolt and later surrendered to battering ram up the ramp with which they began to batter the wall. The The Byzantine Period the Romans at Yodfat. At the time of Masada’s conquest he was in Rome, rebels constructed an inner support wall out of wood and earth, which the where he devoted himself to chronicling the revolt. In spite of the debate Romans then set ablaze. As Josephus describes it, when the hope of the rebels After the Romans left Masada, the fortress remained uninhabited for a few surrounding the accuracy of his accounts, its main features seem to have been dwindled, Eleazar Ben Yair gave two speeches in which he convinced the centuries. During the fifth century CE, in the Byzantine period, a monastery born out by excavation. -

Palestinian Citizens of Israel: Agenda for Change Hashem Mawlawi

Palestinian Citizens of Israel: Agenda for Change Hashem Mawlawi Thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate and Postdoctoral Studies In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Master‘s degree in Conflict Studies School of Conflict Studies Faculty of Human Sciences Saint Paul University © Hashem Mawlawi, Ottawa, Canada, 2019 PALESTINIAN CITIZENS OF ISRAEL: AGENDA FOR CHANGE ii Abstract The State of Israel was established amid historic trauma experienced by both Jewish and Palestinian Arab people. These traumas included the repeated invasion of Palestine by various empires/countries, and the Jewish experience of anti-Semitism and the Holocaust. This culminated in the 1948 creation of the State of Israel. The newfound State has experienced turmoil since its inception as both identities clashed. The majority-minority power imbalance resulted in inequalities and discrimination against the Palestinian Citizens of Israel (PCI). Discussion of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict tends to assume that the issues of the PCIs are the same as the issues of the Palestinians in the Occupied Territories. I believe that the needs of the PCIs are different. Therefore, I have conducted a qualitative case study into possible ways the relationship between the PCIs and the State of Israel shall be improved. To this end, I provide a brief review of the history of the conflict. I explore themes of inequalities and models for change. I analyze the implications of the theories for PCIs and Israelis in the political, social, and economic dimensions. From all these dimensions, I identify opportunities for change. In proposing an ―Agenda for Change,‖ it is my sincere hope that addressing the context of the Israeli-Palestinian relationship may lead to a change in attitude and behaviour that will avoid perpetuating the conflict and its human costs on both sides. -

Algorithmic Handwriting Analysis of Judah's Military Correspondence

Algorithmic handwriting analysis of Judah’s military correspondence sheds light on composition of biblical texts Shira Faigenbaum-Golovina,1,2, Arie Shausa,1,2, Barak Sobera,1,2, David Levina, Nadav Na’amanb, Benjamin Sassc, Eli Turkela, Eli Piasetzkyd, and Israel Finkelsteinc aDepartment of Applied Mathematics, Sackler Faculty of Exact Sciences, Tel Aviv University, Tel Aviv 69978, Israel; bDepartment of Jewish History, Tel Aviv University, Tel Aviv 69978, Israel; cJacob M. Alkow Department of Archaeology and Ancient Near Eastern Civilizations, Tel Aviv University, Tel Aviv 69978, Israel; and dSchool of Physics and Astronomy, Sackler Faculty of Exact Sciences, Tel Aviv University, Tel Aviv 69978, Israel Edited by Klara Kedem, Ben-Gurion University, Be’er Sheva, Israel, and accepted by the Editorial Board March 3, 2016 (received for review November 17, 2015) The relationship between the expansion of literacy in Judah and the fortress of Arad from higher echelons in the Judahite mili- composition of biblical texts has attracted scholarly attention for tary system, as well as correspondence with neighboring forts. over a century. Information on this issue can be deduced from One of the inscriptions mentions “the King of Judah” and Hebrew inscriptions from the final phase of the first Temple another “the house of YHWH,” referring to the Temple in period. We report our investigation of 16 inscriptions from the Jerusalem. Most of the provision orders that mention the Kittiyim— Judahite desert fortress of Arad, dated ca. 600 BCE—the eve of apparently a Greek mercenary unit (7)—were found on the floor ’ Nebuchadnezzar s destruction of Jerusalem. The inquiry is based of a single room. -

Three Conquests of Canaan

ÅA Wars in the Middle East are almost an every day part of Eero Junkkaala:of Three Canaan Conquests our lives, and undeniably the history of war in this area is very long indeed. This study examines three such wars, all of which were directed against the Land of Canaan. Two campaigns were conducted by Egyptian Pharaohs and one by the Israelites. The question considered being Eero Junkkaala whether or not these wars really took place. This study gives one methodological viewpoint to answer this ques- tion. The author studies the archaeology of all the geo- Three Conquests of Canaan graphical sites mentioned in the lists of Thutmosis III and A Comparative Study of Two Egyptian Military Campaigns and Shishak and compares them with the cities mentioned in Joshua 10-12 in the Light of Recent Archaeological Evidence the Conquest stories in the Book of Joshua. Altogether 116 sites were studied, and the com- parison between the texts and the archaeological results offered a possibility of establishing whether the cities mentioned, in the sources in question, were inhabited, and, furthermore, might have been destroyed during the time of the Pharaohs and the biblical settlement pe- riod. Despite the nature of the two written sources being so very different it was possible to make a comparative study. This study gives a fresh view on the fierce discus- sion concerning the emergence of the Israelites. It also challenges both Egyptological and biblical studies to use the written texts and the archaeological material togeth- er so that they are not so separated from each other, as is often the case. -

British Army and Palestine Police Deserters and the Arab–Israeli War

This is a repository copy of British Army and Palestine Police Deserters and the Arab– Israeli War of 1948. White Rose Research Online URL for this paper: http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/135106/ Version: Accepted Version Article: Caden, C and Arielli, N (2021) British Army and Palestine Police Deserters and the Arab– Israeli War of 1948. War in History, 28 (1). pp. 200-222. ISSN 0968-3445 https://doi.org/10.1177/0968344518796688 This is an author produced version of a paper accepted for publication in War in History. Uploaded in accordance with the publisher's self-archiving policy. Reuse Items deposited in White Rose Research Online are protected by copyright, with all rights reserved unless indicated otherwise. They may be downloaded and/or printed for private study, or other acts as permitted by national copyright laws. The publisher or other rights holders may allow further reproduction and re-use of the full text version. This is indicated by the licence information on the White Rose Research Online record for the item. Takedown If you consider content in White Rose Research Online to be in breach of UK law, please notify us by emailing [email protected] including the URL of the record and the reason for the withdrawal request. [email protected] https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/ 1 British Army and Palestine Police Deserters and the Arab-Israeli War of 1948 British servicemen and policemen who had been stationed in Palestine towards the end of the British Mandate and deserted their units to serve with either Jewish or Arab forces have only received cursory academic attention.1 Yet, this is a relatively unique occurrence, in the sense that in no other British withdrawal from colonial territories did members from the security forces desert in notable numbers to remain in the territory to partake in hostilities. -

Palestine About the Author

PALESTINE ABOUT THE AUTHOR Professor Nur Masalha is a Palestinian historian and a member of the Centre for Palestine Studies, SOAS, University of London. He is also editor of the Journal of Holy Land and Palestine Studies. His books include Expulsion of the Palestinians (1992); A Land Without a People (1997); The Politics of Denial (2003); The Bible and Zionism (Zed 2007) and The Pales- tine Nakba (Zed 2012). PALESTINE A FOUR THOUSAND YEAR HISTORY NUR MASALHA Palestine: A Four Thousand Year History was first published in 2018 by Zed Books Ltd, The Foundry, 17 Oval Way, London SE11 5RR, UK. www.zedbooks.net Copyright © Nur Masalha 2018. The right of Nur Masalha to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988. Typeset in Adobe Garamond Pro by seagulls.net Index by Nur Masalha Cover design © De Agostini Picture Library/Getty All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior permission of Zed Books Ltd. A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. ISBN 978‑1‑78699‑272‑7 hb ISBN 978‑1‑78699‑274‑1 pdf ISBN 978‑1‑78699‑275‑8 epub ISBN 978‑1‑78699‑276‑5 mobi CONTENTS Acknowledgments vii Introduction 1 1. The Philistines and Philistia as a distinct geo‑political entity: 55 Late Bronze Age to 500 BC 2. The conception of Palestine in Classical Antiquity and 71 during the Hellenistic Empires (500‒135 BC) 3. -

A Threshold Crossed Israeli Authorities and the Crimes of Apartheid and Persecution WATCH

HUMAN RIGHTS A Threshold Crossed Israeli Authorities and the Crimes of Apartheid and Persecution WATCH A Threshold Crossed Israeli Authorities and the Crimes of Apartheid and Persecution Copyright © 2021 Human Rights Watch All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America ISBN: 978-1-62313-900-1 Cover design by Rafael Jimenez Human Rights Watch defends the rights of people worldwide. We scrupulously investigate abuses, expose the facts widely, and pressure those with power to respect rights and secure justice. Human Rights Watch is an independent, international organization that works as part of a vibrant movement to uphold human dignity and advance the cause of human rights for all. Human Rights Watch is an international organization with staff in more than 40 countries, and offices in Amsterdam, Beirut, Berlin, Brussels, Chicago, Geneva, Goma, Johannesburg, London, Los Angeles, Moscow, Nairobi, New York, Paris, San Francisco, Sydney, Tokyo, Toronto, Tunis, Washington DC, and Zurich. For more information, please visit our website: http://www.hrw.org APRIL 2021 ISBN: 978-1-62313-900-1 A Threshold Crossed Israeli Authorities and the Crimes of Apartheid and Persecution Map .................................................................................................................................. i Summary ......................................................................................................................... 2 Definitions of Apartheid and Persecution ................................................................................. -

The Six-Day War: Israel's Strategy and the Role of Air Power

The Six-Day War: Israel’s Strategy and the Role of Air Power Dr Michael Raska Research Fellow Military Transformations Program [email protected] Ponder the Improbable Outline: • Israel’s Traditional Security Concept 1948 – 1967 – 1973 • The Origins of the Conflict & Path to War International – Regional – Domestic Context • The War: June 5-10, 1967 • Conclusion: Strategic Implications and Enduring Legacy Ponder the Improbable Israel’s Traditional Security Concept 1948 – 1967 – 1973 תפישת הביטחון של ישראל Ponder the Improbable Baseline Assumptions: Security Conceptions Distinct set of generally shared organizing ideas concerning a given state’s national security problems, reflected in the thinking of the country’s political and military elite; Threat Operational Perceptions Experience Security Policy Defense Strategy Defense Management Military Doctrine Strategies & Tactics Political and military-oriented Force Structure Operational concepts and collection of means and ends Force Deployment fundamental principles by through which a state defines which military forces guide their and attempts to achieve its actions in support of objectives; national security; Ponder the Improbable Baseline Assumptions: Israel is engaged in a struggle for its very survival - Israel is in a perpetual state of “dormant war” even when no active hostilities exist; Given conditions of geostrategic inferiority, Israel cannot achieve complete strategic victory neither by unilaterally imposing peace or by military means alone; “Over the years it has become clear -

Partition and Lead-Up to Violence

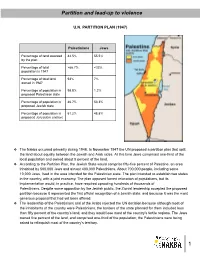

P artition and leadup to violence U.N. PARTITION PLAN (1947) Palestinians Jews Percentage of land awarded 44.5% 55.5% by the plan Percentage of total >66.7% <33% population in 1947 Percentage of total land 93% 7% owned in 1947 Percentage of population in 98.8% 1.2% proposed Palestinian state Percentage of population in 46.7% 53.3% proposed Jewish state Percentage of population in 51.2% 48.8% proposed Jerusalem enclave ❖ The Nakba occurred primarily during 1948. In November 1947 the UN proposed a partition plan that split the land about equally between the Jewish and Arab sides. At this time Jews comprised onethird of the local population and owned about 5 percent of the land. ❖ According to the Partition Plan, the Jewish State would comprise fiftyfive percent of Palestine, an area inhabited by 500,000 Jews and almost 400,000 Palestinians. About 700,000 people, including some 10,000 Jews, lived in the area intended for the Palestinian state. The plan intended to establish two states in the country, with a joint economy. The plan opposed forced relocation of populations, but its implementation would, in practice, have required uprooting hundreds of thousands of Palestinians. Despite some opposition by the Jewish public, the Zionist leadership accepted the proposed partition because it represented the first official recognition of a Jewish state, and because it was the most generous proposal that had yet been offered. ❖ The leadership of the Palestinians and of the Arabs rejected the UN decision because although most of the inhabitants of the country were Palestinians, the borders of the state planned for them included less than fifty percent of the country’s land, and they would lose most of the country’s fertile regions. -

B'tselem Report: Dispossession & Exploitation: Israel's Policy in the Jordan Valley & Northern Dead Sea, May

Dispossession & Exploitation Israel's policy in the Jordan Valley & northern Dead Sea May 2011 Researched and written by Eyal Hareuveni Edited by Yael Stein Data coordination by Atef Abu a-Rub, Wassim Ghantous, Tamar Gonen, Iyad Hadad, Kareem Jubran, Noam Raz Geographic data processing by Shai Efrati B'Tselem thanks Salwa Alinat, Kav LaOved’s former coordinator of Palestinian fieldworkers in the settlements, Daphna Banai, of Machsom Watch, Hagit Ofran, Peace Now’s Settlements Watch coordinator, Dror Etkes, and Alon Cohen-Lifshitz and Nir Shalev, of Bimkom. 2 Table of contents Introduction......................................................................................................................... 5 Chapter One: Statistics........................................................................................................ 8 Land area and borders of the Jordan Valley and northern Dead Sea area....................... 8 Palestinian population in the Jordan Valley .................................................................... 9 Settlements and the settler population........................................................................... 10 Land area of the settlements .......................................................................................... 13 Chapter Two: Taking control of land................................................................................ 15 Theft of private Palestinian land and transfer to settlements......................................... 15 Seizure of land for “military needs”.............................................................................