Implementation of Forest Rights Act in Gudalur

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

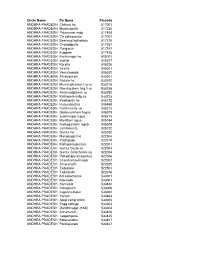

Post Offices

Circle Name Po Name Pincode ANDHRA PRADESH Chittoor ho 517001 ANDHRA PRADESH Madanapalle 517325 ANDHRA PRADESH Palamaner mdg 517408 ANDHRA PRADESH Ctr collectorate 517002 ANDHRA PRADESH Beerangi kothakota 517370 ANDHRA PRADESH Chowdepalle 517257 ANDHRA PRADESH Punganur 517247 ANDHRA PRADESH Kuppam 517425 ANDHRA PRADESH Karimnagar ho 505001 ANDHRA PRADESH Jagtial 505327 ANDHRA PRADESH Koratla 505326 ANDHRA PRADESH Sirsilla 505301 ANDHRA PRADESH Vemulawada 505302 ANDHRA PRADESH Amalapuram 533201 ANDHRA PRADESH Razole ho 533242 ANDHRA PRADESH Mummidivaram lsg so 533216 ANDHRA PRADESH Ravulapalem hsg ii so 533238 ANDHRA PRADESH Antarvedipalem so 533252 ANDHRA PRADESH Kothapeta mdg so 533223 ANDHRA PRADESH Peddapalli ho 505172 ANDHRA PRADESH Huzurabad ho 505468 ANDHRA PRADESH Fertilizercity so 505210 ANDHRA PRADESH Godavarikhani hsgso 505209 ANDHRA PRADESH Jyothinagar lsgso 505215 ANDHRA PRADESH Manthani lsgso 505184 ANDHRA PRADESH Ramagundam lsgso 505208 ANDHRA PRADESH Jammikunta 505122 ANDHRA PRADESH Guntur ho 522002 ANDHRA PRADESH Mangalagiri ho 522503 ANDHRA PRADESH Prathipadu 522019 ANDHRA PRADESH Kothapeta(guntur) 522001 ANDHRA PRADESH Guntur bazar so 522003 ANDHRA PRADESH Guntur collectorate so 522004 ANDHRA PRADESH Pattabhipuram(guntur) 522006 ANDHRA PRADESH Chandramoulinagar 522007 ANDHRA PRADESH Amaravathi 522020 ANDHRA PRADESH Tadepalle 522501 ANDHRA PRADESH Tadikonda 522236 ANDHRA PRADESH Kd-collectorate 533001 ANDHRA PRADESH Kakinada 533001 ANDHRA PRADESH Samalkot 533440 ANDHRA PRADESH Indrapalem 533006 ANDHRA PRADESH Jagannaickpur -

Nilgiris District, Tamil Nadu Connie Smith Tamil Nadu Overview

Nilgiris District, Tamil Nadu Connie Smith Tamil Nadu Overview Tamil Nadu is bordered by Pondicherry, Kerala, Karnataka and Andhra Pradesh. Sri Lanka, which has a significant Tamil minority, lies off the southeast coast. Tamil Nadu, with its traceable history of continuous human habitation since pre-historic times has cultural traditions amongst the oldest in the world. Colonised by the East India Company, Tamil Nadu was eventually incorporated into the Madras Presidency. After the independence of India, the state of Tamil Nadu was created in 1969 based on linguistic boundaries. The politics of Tamil Nadu has been dominated by DMK and AIADMK, which are the products of the Dravidian movement that demanded concessions for the 'Dravidian' population of Tamil Nadu. Lying on a low plain along the southeastern coast of the Indian peninsula, Tamil Nadu is bounded by the Eastern Ghats in the north and Nilgiri, Anai Malai hills and Palakkad (Palghat Gap) on the west. The state has large fertile areas along the Coromandel coast, the Palk strait, and the Gulf of Mannar. The fertile plains of Tamil Nadu are fed by rivers such as Kaveri, Palar and Vaigai and by the northeast monsoon. Traditionally an agricultural state, Tamil Nadu is a leading producer of agricultural products. Tribal Population As per 2001 census, out of the total state population of 62,405,679, the population of Scheduled Castes is 11,857,504 and that of Scheduled Tribes is 651,321. This constitutes 19% and 1.04% of the total population respectively.1 Further, the literacy level of the Adi Dravidar is only 63.19% and that of Tribal is 41.53%. -

IMA TNSB- WEST ZONE Local Branch Presidents & Secretaries

IMA TNSB- WEST ZONE Local Branch Presidents & Secretaries - 2018 Name of Secretary President Branch Dr. Eswaramoorthy. K Dr. Saira President, IMA Anamalai Branch Hony. Secretary, IMA Anamalai Branch, Chief Medical Officer, TATA Coffee Limited Anamalai Uralikal Estate, General Hospital Uralikal Estate, General Hospital Valparai- 642 127. 04253 292333 Valparai- 642 127. Dr. A.V. Shanmugam, Hony. Secretary, IMA Annur Branch, Annur R.V.R. Hospital, Sathy Road, Annur – 638 653. 9965598598 Dr. K.V. Selvakumar Dr. Senthil Kumar President, IMA Anthiyur Branch, Hony. Secretary, IMA Anthiyur Branch Sri Arungani Hospital Ravi Hopsital, Anthiyur 153, Velayutham Street, Anthiyur – 638 501. Thavittupalayam, Anthiyur – 638 501. Cell : 98427 16176 04256- 260365, Cell : 9965560365 [email protected] Attur Dr. R. Rabindranath Dr. M. ARUNKUMAR President, IMA Attur Branch Hony. Secretary, IMA Attur Branch www.attur.org/im Geeth Ragunath Hospital Kumar Eye Hospital, a No. 2, Gandhi Nagar, Attur – 636 102. 470, Kamarajanar Road [email protected] m Cell : 98427 50556 Attur – 636 102. Cell : 94437 12738 8838554152 [email protected] [email protected] arokiyaraj Dr. P. Nandagopalsamy Dr. A. Hairsh Batlagundu President, IMA Batlagundu Branch Hony. Secretary, IMA Batlagundu Branch, imabtlbranch@g mail.com Leonard Hospital, Muthu Clinic, Nilakottai Batlagundu. Cell : 98946 31579 Cell : 80123 42424 Dr. K.P. Saravanan Dr. K.P. Arun President, IMA Bhavani Komarapalayam Hony. Secretary, IMA Bhavani No 430, Balaji Child Care Center, Komarapalayam Bhavani – Opp. New Bus Stand, Mettur Road, Jaswant Gastro Care Clinic, Komarapalay Bhavani – 638 501. Erode District. Opp. State Bank of India, am Cell : 97889 06505 Bhavani – 638 301. Erode District. e.mail : [email protected] Cell : 97502 64111 e.mail : [email protected] Coimbatore Dr. -

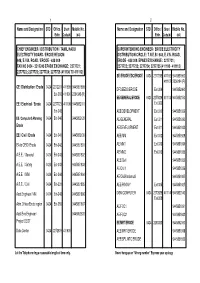

Erode Region/ Distribution Circle / T.N.E.B / 948, E.V.N

1 2 Name and Designation STD Office / Short Mobile No. Name and Designation STD Office / Short Mobile No. Extn. Code(#) (#4) Extn. Code(#) (#4) CHIEF ENGINEER / DISTRIBUTION / TAMIL NADU SUPERINTENDING ENGINEER / ERODE ELECTRICITY ELECTRICITY BOARD / ERODE REGION/ DISTRIBUTION CIRCLE / T.N.E.B / 948, E.V.N. ROAD, 948, E.V.N. ROAD / ERODE - 638 009 ERODE - 638 009. EPABX EXCHANGE: 2277721; FAX NO 0424 - 2217245 EPABX EXCHANGE: 2277721; 2277722; 2277723; 2277724; 2277725 (411108 - 411112) 2277722; 2277723; 2277724; 2277725 (411108 TO 411112) SE /ERODE EDC/ERODE 0424 2217245 411106 9445851900 411107 2256194 (R) CE / Distribution / Erode 0424 2272207 411599 9445851999 DFC/EEDC/ERODE Ext-304 9445852460 Ext-300 411601 2264343 (R) EE/GENERAL/ERODE 0424 2275829 411113 9445852150 EE / Electrical / Erode 0424 2277721 411108 9445852110 Ext-302 Ext-345 AEE/DEVELOPMENT Ext-310 9445851926 EE / Computer & Planning 0424 Ext-346 9445852120 AE/GENERAL Ext-311 9445851930 Erode AE/DEVELOPMENT Ext-311 9445851933 EE / Civil / Erode 0424 Ext-341 9445852130 AEE/MM Ext-312 9445851928 EA to CE/D/ Erode 0424 Ext-342 9445851801 AE/MM1 Ext-313 9445851934 AE/MM2 Ext-313 9445851935 A.E.E. / General 0424 Ext-343 9445851802 AEE/Civil 9445851929 A.E.E. / Safety 0424 Ext-343 9445851803 AE/Civil1 9445851936 A.E.E. / MM 0424 Ext-344 9445851804 AE/Civil/Kodumudi 9445851937 A.E.E. / Civil 0424 Ext-331 9445851805 AEE/RGGVY Ext-305 9445851927 Asst.Engineer/ MM 0424 Ext-348 9445851806 DGM/COMPUTER 0424 2272829 411114 9445852140 Ext-308 Adm.Officer/Erode region 0424 Ext-350 9445851807 AE/FOC1 9445851931 Asst.Exe.Engineer/ 9445852520 AE/FOC2 9445851932 Project BEST EE/MRT/ERODE 0424 2263323 9445852160 Data Center 0424 2272819 411600 AEE/MRT/ERODE 9445851938 AEE/SPL.MTC/ERODE 9445851939 Let the Telephone ring a reasonable length of time only. -

Coimbatore Commissionerate Jurisdiction

Coimbatore Commissionerate Jurisdiction The jurisdiction of Coimbatore Commissionerate will cover the areas covering the entire Districts of Coimbatore, Nilgiris and the District of Tirupur excluding Dharapuram, Kangeyam taluks and Uthukkuli Firka and Kunnathur Firka of Avinashi Taluk * in the State of Tamil Nadu. *(Uthukkuli Firka and Kunnathur Firka are now known as Uthukkuli Taluk). Location | 617, A.T.D. STR.EE[, RACE COURSE, COIMBATORE: 641018 Divisions under the jurisdiction of Coimbatore Commissionerate Sl.No. Divisions L. Coimbatore I Division 2. Coimbatore II Division 3. Coimbatore III Division 4. Coimbatore IV Division 5. Pollachi Division 6. Tirupur Division 7. Coonoor Division Page 47 of 83 1. Coimbatore I Division of Coimbatore Commissionerate: Location L44L, ELGI Building, Trichy Road, COIMBATORT- 641018 AreascoveringWardNos.l to4,LO to 15, 18to24and76 to79of Coimbatore City Municipal Corporation limit and Jurisdiction Perianaickanpalayam Firka, Chinna Thadagam, 24-Yeerapandi, Pannimadai, Somayampalayam, Goundenpalayam and Nanjundapuram villages of Thudiyalur Firka of Coimbatore North Taluk and Vellamadai of Sarkar Samakulam Firka of Coimbatore North Taluk of Coimbatore District . Name of the Location Jurisdiction Range Areas covering Ward Nos. 10 to 15, 20 to 24, 76 to 79 of Coimbatore Municipal CBE Corporation; revenue villages of I-A Goundenpalayam of Thudiyalur Firka of Coimbatore North Taluk of Coimbatore 5th Floor, AP Arcade, District. Singapore PIaza,333 Areas covering Ward Nos. 1 to 4 , 18 Cross Cut Road, Coimbatore Municipal Coimbatore -641012. and 19 of Corporation; revenue villages of 24- CBE Veerapandi, Somayampalayam, I-B Pannimadai, Nanjundapuram, Chinna Thadagam of Thudiyalur Firka of Coimbatore North Taluk of Coimbatore District. Areas covering revenue villages of Narasimhanaickenpalayam, CBE Kurudampalayam of r-c Periyanaickenpalayam Firka of Coimbatore North Taluk of Coimbatore District. -

Community List

ANNEXURE - III LIST OF COMMUNITIES I. SCHEDULED TRIB ES II. SCHEDULED CASTES Code Code No. No. 1 Adiyan 2 Adi Dravida 2 Aranadan 3 Adi Karnataka 3 Eravallan 4 Ajila 4 Irular 6 Ayyanavar (in Kanyakumari District and 5 Kadar Shenkottah Taluk of Tirunelveli District) 6 Kammara (excluding Kanyakumari District and 7 Baira Shenkottah Taluk of Tirunelveli District) 8 Bakuda 7 Kanikaran, Kanikkar (in Kanyakumari District 9 Bandi and Shenkottah Taluk of Tirunelveli District) 10 Bellara 8 Kaniyan, Kanyan 11 Bharatar (in Kanyakumari District and Shenkottah 9 Kattunayakan Taluk of Tirunelveli District) 10 Kochu Velan 13 Chalavadi 11 Konda Kapus 14 Chamar, Muchi 12 Kondareddis 15 Chandala 13 Koraga 16 Cheruman 14 Kota (excluding Kanyakumari District and 17 Devendrakulathan Shenkottah Taluk of Tirunelveli District) 18 Dom, Dombara, Paidi, Pano 15 Kudiya, Melakudi 19 Domban 16 Kurichchan 20 Godagali 17 Kurumbas (in the Nilgiris District) 21 Godda 18 Kurumans 22 Gosangi 19 Maha Malasar 23 Holeya 20 Malai Arayan 24 Jaggali 21 Malai Pandaram 25 Jambuvulu 22 Malai Vedan 26 Kadaiyan 23 Malakkuravan 27 Kakkalan (in Kanyakumari District and Shenkottah 24 Malasar Taluk of Tirunelveli District) 25 Malayali (in Dharmapuri, North Arcot, 28 Kalladi Pudukkottai, Salem, South Arcot and 29 Kanakkan, Padanna (in the Nilgiris District) Tiruchirapalli Districts) 30 Karimpalan 26 Malayakandi 31 Kavara (in Kanyakumari District and Shenkottah 27 Mannan Taluk of Tirunelveli District) 28 Mudugar, Muduvan 32 Koliyan 29 Muthuvan 33 Koosa 30 Pallayan 34 Kootan, Koodan (in Kanyakumari District and 31 Palliyan Shenkottah Taluk of Tirunelveli District) 32 Palliyar 35 Kudumban 33 Paniyan 36 Kuravan, Sidhanar 34 Sholaga 39 Maila 35 Toda (excluding Kanyakumari District and 40 Mala Shenkottah Taluk of Tirunelveli District) 41 Mannan (in Kanyakumari District and Shenkottah 36 Uraly Taluk of Tirunelveli District) 42 Mavilan 43 Moger 44 Mundala 45 Nalakeyava Code III (A). -

Tamil Nadu Panchayat Development Service – Assistant Director of Rural Development - Direct Recruitment for the Year 2006-07 –– Appointment - Orders Issued

ABSTRACT Public Services - Tamil Nadu Panchayat Development Service – Assistant Director of Rural Development - Direct Recruitment for the year 2006-07 –– Appointment - Orders Issued. --------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- RURAL DEVELOPMENT AND PANCHAYAT RAJ (E1) DEPARTMENT G.O.Ms.No.105 Dated : 19.09.2009 Read : From the Secretary, Tamil Nadu Public Service Commission, Letter No.6667/OTD C1/2007, dated 18-09-2009. * * * * ORDER : In the letter read above, the Tamil Nadu Public Service Commission has forwarded the name of following 26 candidates selected through competitive examination under Group-I Services for appointment to the post of Assistant Director of Rural Development / Personal Assistant to Collector (Development) by direct recruitment for the year 2006-07, subject to the result of the Writ Petitions pending before the High Court of Madras and Madurai Bench of Madras High Court. 2. The Government approve the selection of candidates as communicated by the Tamil Nadu Public Service Commission for appointment as Assistant Director of Rural Development/ Personal Assistant to collector (Development) in the Tamil Nadu Panchayat Development Service for the year 2006-07. 3. The following 26 candidates are hereby regularly appointed as Assistant Director / Personal Assistant to Collector (Development) by Direct Recruitment in the Tamil Nadu Panchayat Development Service in the scale of pay of Rs.8,000-275-13500 (Pre-revised scale) and posted for training in the Districts noted against each as indicated below subject to the result of the Writ Petitions pending before the High Court of Madras and Madurai Bench of Madras High Court. ..2.. S.No Name of the Candidate District allotted 1 Tmt/Selvi.Kanchana, B. -

TO, 1 District Librarian, Salem District Central Library, Chera Rajan Salai

TO, District Librarian, TO, Librarian, 1 Salem District Central Library, 2 Thirumal City Branch Library, Chera rajan Salai, Kamaraj Vedding Building, Asthamppaty Main Road, Municipaliti Chess colection Salem- 636 007. Center Office Near Rajethira Shathiram, Salem- 636 009. TO, Librarian, TO, Librarian, 3 Swarnapuri Branch Library, 4 Ammapet Branch Library, Selva Vinayagar Temple Street, 84-B, Kanaga sapathi Street, SwarnapuriPost, Ammapet Post Office, Salem- 636 004. Salem- 636 003. TO, Librarian, TO, Librarian, 5 Ayothiya pattinam Branch Library, 6 Panamarthupatty Branch Library, Belur Main Road, Thiruvalluvar Road, Ayothiya pattinamPost, PanamarthupattyPost, Salem Taluk, Salem District- 636 203. SalemDistrict - 636 202. TO, Librarian, TO, Librarian, 7 Attaiyampatti Branch Library, 8 Vembatydhalam Branch Library, Attaiyampatti Gov Gir Hir Sce 2/245, Near Post offic Street, School Near Attaiyampatti Post,, VembatydhalamPost, Salem Taluk, SalemTaluk, Salem District- 636 501. Salem District- 637 504. TO, Librarian, TO, Librarian, 9 MallurBranch Library, 10 Sooramangalam Branch Library, 1/25 Athikuttai, 207, SooramangalamMain Road, MallurPost, Salem Taluk, SalemTaluk, Salem District- 636 005. Salem District- 636 203. TO, Librarian, TO, Librarian, 11 Minnampalli Branch Library, 12 Sivathapuram Branch Library, Mariyamman Temple Street, Maiyan Street, Minnampalli Post, Sivathapuram Post, Salem Taluk, Mariyamman Temple Street Near Salem District- 636 106. SalemTaluk, Salem District- 636 301. TO, Librarian, TO, Librarian, 13 Gugai Branch Library, 14 Palaniyamal Raja K.V Iyan Thiruvalluvar memoriyal, Branch Library, Ampalvana Swamy Temple Street, 26, Vallar Street, GugaiPost, KanangkuruchiPost, SalemTaluk, SalemTaluk, Salem District- 636 006. Salem District- 636 008. TO, Librarian, TO, Librarian, 15 Kondalampatty Branch Library, 16 Dhasanayakkanpatty Branch Muniappan Temple Street-3, Library, Ward No-10, 5/85, Thuruchy Main Road, KondalampattyPost, DhasanayakkanpattyPost, SalemTaluk, SalemTaluk, Salem District- 636 010. -

Tamil Nadu Government Gazette

© [Regd. No. TN/CCN/467/2012-14. GOVERNMENT OF TAMIL NADU [R. Dis. No. 197/2009. 2013 [Price: Rs. 27.20 Paise. TAMIL NADU GOVERNMENT GAZETTE PUBLISHED BY AUTHORITY No. 10] CHENNAI, WEDNESDAY, MARCH 13, 2013 Maasi 29, Nandhana, Thiruvalluvar Aandu–2044 Part VI—Section 4 Advertisements by private individuals and private institutions CONTENTS PRIVATE ADVERTISEMENTS Pages Change of Names .. 553-619 Notice .. 620 NOTICE NO LEGAL RESPONSIBILITY IS ACCEPTED FOR THE PUBLICATION OF ADVERTISEMENTS REGARDING CHANGE OF NAME IN THE TAMIL NADU GOVERNMENT GAZETTE. PERSONS NOTIFYING THE CHANGES WILL REMAIN SOLELY RESPONSIBLE FOR THE LEGAL CONSEQUENCES AND ALSO FOR ANY OTHER MISREPRESENTATION, ETC. (By Order) Director of Stationery and Printing. CHANGE OF NAMES 8416. I, Barakathu Nisha, wife of Thiru Syed Ahamed 8419. My son, P. Jayakodi, born on 10th October 2010 Kabeer, born on 1st April 1966 (native district: (native district: Virudhunagar), residing at Old No. 8-23, New Ramanathapuram), residing at Old No. 4-66, New No. 4/192, No. 8-99, West Street, Veeranapuram, Kalingapatti, Chittarkottai Post, Ramanathapuram-623 513, shall henceforth Sankarankoil Taluk, Tirunelveli-627 753, shall henceforth be be known as BARAKATH NEESHA. known as V.P. RAJA. BARAKATHU NISHA. M. PERUMALSAMY. Ramanathapuram, 4th March 2013. Tirunelveli, 4th March 2013. (Father.) 8420. I, Sarika Kantilal Rathod, wife of Thiru Shripal, born 8417. I, S Rasia Begam, wife of Thiru M. Sulthan, born on on 3rd February 1977 (native district: Chennai), residing at 2nd June 1973 (native district: Dindigul), residing at Old No. 140-13, Periyasamy Road, R.S. Puram Post, Coimbatore- No. 4/115-E, New No. -

ERODE Sl.No Division Sub-Division Name & Address of the Office With

ERODE Details of Locations with Land Line & Bandwidth - 256 Kbps No. of PCs Name & Address of the office with Land Line connected with Existing Proposed Sl.No Division Sub-Division Contact Number where VPNoBB Number the VPNoBB Bandwidth Bandwidth Connectivity is available connectivity AE/O&M/S/Chithode,Indra Nagar, Urban / 1 Chithode Naduppalayam, 0424-2534848 4 256 256 Erode Chithode - 638 455 South / C&I/South/ AE/O&M/Solar, 2 0424-2401007 4 256 256 Erode Erode Iraniyan St,Solar Asst.Engineer,O&M/Gugai, AEE/O&M/Gugai, D.No.17/26 , 3 Gugai 0427-2464499 4 256 256 Ramalingamadalaya Street,Gugai,Salem Town/ Salem Asst.Engineer,O&M/ Linemedu/ Salem/TNEB 4 Gugai 0427-2218747 4 256 256 D.No.60,Ramalingamsamy Koil St, Linemedu Gugai Salem 6. Asst.Engineer,O&M/ Kalarampatty/Salem/TNEB, 5 0427-2468791 4 256 256 D.No.13, Nethaji St., Town/ Salem Kitchi palayam Kalarampatty,Salem 636015 Junior.Engineer,O&M/ 6 Dadagapatty/TNEB,Shanmuga 0427-2273586 4 256 256 nagar, dadagapatty Salem 636006 Asst.Engineer,O&M/ 7 Swarnapuri Mallamooppampatti/TNEB, Sundar 0427-2386400 4 256 256 nagar,Salem 636302 West/ Salem Asst.Engineer,O&M/ Narasothipatti/TNEB, 5/71-b2,PG 8 Swarnapuri 0427-2342288 4 256 256 Nagar, Jagirammapalayam.Salem 636302 Asst.Engineer,O&M/ 9 Town/ Salem Gugai Seelanaickenpatty/ Salem,SF.No.93, 0427-2281236 4 256 256 Seelanaickenpatty bypass, Salem Asst.Engineer,O&M/ 10 Suramangalam Rural/Nethimedu/TNEB, Circle 0427-2274466 4 256 256 Thottam /Nethimedu, Salem West/ Salem 636002 West/ Salem Asst.Engineer,O&M/ 11 Shevapet Kondalampatti/TNEB, 7/65 -

Census Handbook, Nilgiris

1.951 CENSUS HANDBOOK THE NILGIRIS DISTRICT PRINTED BY THE SUPERINTENDENT GOVERNMENT PRESS MADRAS 1 953 CONTENTS PAGE PART I----oont· 1 PRE!!'A.qlII Section (ii). 2 IntrodUctory note about the district, with anne:s:ures. 1 S Rural StalistiC8-(fuformation regarding area, number STATISTICS. of occupied houses, literacy; distribution of popula· tion by livilihood classes, c~ltivated area. amaD·scale PART I. industriul establishments a,Dd incidence of leprosy in villages) with appendix giving a list of villages Sec'ion ( i ). with a populatiO'n exceeding 5,00Q but treated as rural. 3' .. A " General Po-pulation Tables- I Section (iii). ; A-I-Area, Houses and Population 8 9 Urban Stati8tics-(lnformation regarding area, numoor A-II-Variation in Population during fifty years 8 of occupied houses, liter~cy. distribution of popula.· tion by livelihood classes, small-sca.le indua¥al estab· A.III-Towns and Villages classified by Population 9 lishments 'and incidence of leprosy in each ward of Talukwar. each census town and city.) A-IV-Cities and Towns classified by population with 11 PAltT II. variati()ns since 1901. 10 •• C ,. HO'U8eh~ld and Age (Sample) Tables A-V-Towns arranged talukwise with Population by 12 Livelihood Classes. C·I-Household (size) . M C;II-Livelihood Classes by Age Groups 55 4 "E " Summal'Y figures by taluks 13 C·IV-Age and Literacy 58 [} .. B " Economic Tables- 11 .. D" Social and Cultural Tables- B-I-Livehhood Classes and Sub·classes 15 D·I-La.nguagea- B·Il-Secondary means of livelihood l~ (i) Mother·tongue 00 B·llI-Employers, Employees and Independent 21 (ii) Bil.ingualism 62- Workers in Industries and Services by Divisions and Subdivisions. -

A Study on Socio-Economic and Health Conditions of the Tribal Peoples of the Nilgiri District-Tamil Nadu

Imperial Journal of Interdisciplinary Research (IJIR) Vol-3, Issue-1, 2017 ISSN: 2454-1362, http://www.onlinejournal.in A Study on Socio-Economic and Health Conditions of the Tribal Peoples of the Nilgiri District-Tamil Nadu 1 Dr.S.Ponnarasu & 2 S.Madevan 1Assistant Professor, Department of Economics, Gobi Arts & Science College, Gobichettipalayam. 2PhD Research Scholar Department of Economics Gobi Arts & Science College Gobichettipalayam Abstract : The Nilgiris is the moderately populated To explore about the socio economic district of Tamil Nadu that has a rich tribal conditions of the tribal peoples presence. There are about– tribes living in different To find the availability and adequacy of parts of the district. Nilgiris has – lakh of tribal healthcare facilities in the study area people which are just above – percent of total population of Tamil Nadu. The tribal people differ TRIBAL POPULATION in their social organizations and marital customs Although the Census of 2011 enumerates rites and rituals, foods and other customs from the the total population of Scheduled Tribes at people of the rest of the state. Most of the tribal 10,42,81,034 persons, constituting 8.6 per cent of people speak in their own languages. This paper the population of the country, the tribal presents current socio conditions of the tribal communities in India are enormously diverse and peoples and to find the availability and adequacy heterogeneous. There are wide ranging diversities of healthcare facilities in the study area. among them in respect of languages spoken, size of population and mode of livelihood. The number of Keywords: Socio economic, Healthcare.