Laws and Natural Properties

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2. Aristotle's Concept of the State

Page No.13 2. Aristotle's concept of the state Olivera Z. Mijuskovic Full Member International Association of Greek Philosophy University of Athens, Greece ORCID iD: http://orcid.org/0000-0001-5950-7146 URL: http://worldphilosophynetwork.weebly.com E-Mail: [email protected] Abstract: In contrast to a little bit utopian standpoint offered by Plato in his teachings about the state or politeia where rulers aren`t “in love with power but in virtue”, Aristotle's teaching on the same subject seems very realistic and pragmatic. In his most important writing in this field called "Politics", Aristotle classified authority in the form of two main parts: the correct authority and moose authority. In this sense, correct forms of government are 1.basileus, 2.aristocracy and 3.politeia. These forms of government are based on the common good. Bad or moose forms of government are those that are based on the property of an individual or small governmental structures and they are: 1.tiranny, 2.oligarchy and 3.democracy. Also, Aristotle's political thinking is not separate from the ethical principles so he states that the government should be reflected in the true virtue that is "law" or the "golden mean". Keywords: Government; stat; , virtue; democracy; authority; politeia; golden mean. Vol. 4 No. 4 (2016) Issue- December ISSN 2347-6869 (E) & ISSN 2347-2146 (P) Aristotle's concept of the state by Olivera Z. Mijuskovic Page no. 13-20 Page No.14 Aristotle's concept of the state 1.1. Aristotle`s “Politics” Politics in its defined form becomes affirmed by the ancient Greek world. -

Some Thoughts About Natural Law

Some Thoughts About Natural Law Phflip E. Johnsont My first task is to define the subject. When I use the term "natural" law, I am distinguishing the category from other kinds of law such as positive law, divine law, or scientific law. When we discuss positive law, we look to materials like legislation, judicial opinions, and scholarly anal- ysis of these materials. If we speak of divine law, we ask if there are any knowable commands from God. If we look for scientific law, we conduct experiments, or make observations and calculations, in order to come to objectively verifiable knowledge about the material world. Natural law-as I will be using the term in this essay-refers to a method that we employ to judge what the principles of individual moral- ity or positive law ought to be. The natural law philosopher aspires to make these judgments on the basis of reason and human nature without invoking divine revelation or prophetic inspiration. Natural law so defined is a category much broader than any particular theory of natural law. One can believe in the existence of natural law without agreeing with the particular systems of natural law advocates like Aristotle or Aquinas. I am describing a way of thinking, not a particular theory. In the broad sense in which I am using the term, therefore, anyone who attempts to found concepts of justice upon reason and human nature engages in natural law philosophy. Contemporary philosophical systems based on feminism, wealth maximization, neutral conversation, liberal equality, or libertarianism are natural law philosophies. -

Scientific Explanation

Scientific Explanation Michael Strevens For the Macmillan Encyclopedia of Philosophy, second edition The three cardinal aims of science are prediction, control, and expla- nation; but the greatest of these is explanation. Also the most inscrutable: prediction aims at truth, and control at happiness, and insofar as we have some independent grasp of these notions, we can evaluate science’s strate- gies of prediction and control from the outside. Explanation, by contrast, aims at scientific understanding, a good intrinsic to science and therefore something that it seems we can only look to science itself to explicate. Philosophers have wondered whether science might be better off aban- doning the pursuit of explanation. Duhem (1954), among others, argued that explanatory knowledge would have to be a kind of knowledge so ex- alted as to be forever beyond the reach of ordinary scientific inquiry: it would have to be knowledge of the essential natures of things, something that neo-Kantians, empiricists, and practical men of science could all agree was neither possible nor perhaps even desirable. Everything changed when Hempel formulated his dn account of ex- planation. In accordance with the observation above, that our only clue to the nature of explanatory knowledge is science’s own explanatory prac- tice, Hempel proposed simply to describe what kind of things scientists ten- dered when they claimed to have an explanation, without asking whether such things were capable of providing “true understanding”. Since Hempel, the philosophy of scientific explanation has proceeded in this humble vein, 1 seeming more like a sociology of scientific practice than an inquiry into a set of transcendent norms. -

Two Concepts of Law of Nature

Prolegomena 12 (2) 2013: 413–442 Two Concepts of Law of Nature BRENDAN SHEA Winona State University, 528 Maceman St. #312, Winona, MN, 59987, USA [email protected] ORIGINAL SCIENTIFIC ARTICLE / RECEIVED: 04–12–12 ACCEPTED: 23–06–13 ABSTRACT: I argue that there are at least two concepts of law of nature worthy of philosophical interest: strong law and weak law . Strong laws are the laws in- vestigated by fundamental physics, while weak laws feature prominently in the “special sciences” and in a variety of non-scientific contexts. In the first section, I clarify my methodology, which has to do with arguing about concepts. In the next section, I offer a detailed description of strong laws, which I claim satisfy four criteria: (1) If it is a strong law that L then it also true that L; (2) strong laws would continue to be true, were the world to be different in some physically possible way; (3) strong laws do not depend on context or human interest; (4) strong laws feature in scientific explanations but cannot be scientifically explained. I then spell out some philosophical consequences: (1) is incompatible with Cartwright’s contention that “laws lie” (2) with Lewis’s “best-system” account of laws, and (3) with contextualism about laws. In the final section, I argue that weak laws are distinguished by (approximately) meeting some but not all of these criteria. I provide a preliminary account of the scientific value of weak laws, and argue that they cannot plausibly be understood as ceteris paribus laws. KEY WORDS: Contextualism, counterfactuals, David Lewis, laws of nature, Nancy Cartwright, physical necessity. -

BY PLATO• ARISTOTLE • .AND AQUINAS I

i / REF1,l!;CTit.>NS ON ECONOMIC PROBLEMS / BY PLATO• ARISTOTLE • .AND AQUINAS ii ~FLECTIONS ON ECONO:MIC PROBLEMS 1 BY PLA'I'O, ARISTOTLE, JJJD AQUINAS, By EUGENE LAIDIBEL ,,SWEARINGEN Bachelor of Science Oklahoma Agricultural and Mechanical Collage Stillwater, Oklahoma 1941 Submitted to the Depertmeut of Economics Oklahoma Agricultural and Mechanical College In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE 1948 iii f.. 'I. I ···· i·: ,\ H.: :. :· ··: ! • • ~ ' , ~ • • !·:.· : i_ ·, 1r 1i1. cr~~rJ3t L l: i{ ,\ I~ Y , '•T •)() 1 0 ,1 8 API-'HOV~D BY: .J ,.· 1.., J l.;"t .. ---- -··- - ·- ______.,.. I 7 -.. JI J ~ L / \ l v·~~ u ' ~) (;_,LA { 7 {- ' r ~ (\.7 __\ _. ...A'_ ..;f_ ../-_" ...._!)_.... ..." ___ ......._ ·;...;;; ··-----/ 1--.,i-----' ~-.._.._ :_..(__,,---- ....... Member of the Report Committee 1..j lj:,;7 (\ - . "'·- -· _ .,. ·--'--C. r, .~-}, .~- Q_ · -~ Q.- 1Head of the Department . · ~ Dean of the Graduate School 502 04 0 .~ -,. iv . r l Preface The purpose and plan of this report are set out in the Introduction. Here, I only wish to express my gratitude to Professor Russell H. Baugh who has helped me greatly in the preparation of this report by discussing the various subjects as they were in the process of being prepared. I am very much indebted to Dr. Harold D. Hantz for his commentaries on the report and for the inspiration which his classes in Philosophy have furnished me as I attempted to correlate some of the material found in these two fields, Ecor!.Omics and Philosophy. I should like also to acknowledge that I owe my first introduction into the relationships of Economics and Philosophy to Dean Raymond Thomas, and his com~ents on this report have been of great value. -

Editorial Introduction to 'Truth: Concept Meets Property'

Synthese (2021) 198 (Suppl 2):S591–S603 https://doi.org/10.1007/s11229-020-02711-2 S.I. : TRUTH: CONCEPT MEETS PROPERTY Editorial introduction to ‘truth: concept meets property’ Jeremy Wyatt1 Published online: 25 May 2020 © Springer Nature B.V. 2020 1 Concepts versus properties The papers in this special issue investigate a range of topics that pertain to the dis- tinction between the concept and the property of truth. The distinction between property concepts and the properties that they pick out is a mainstay within analytic philosophy. We have learned to distinguish, for instance, between our ordinary con- 1 cept SIMULTANEOUS and the property simultaneity that it picks out. The signifcance of this distinction is borne out in the theories of reference that were developed, for instance, by Putnam (1975), Kripke (1980), and Lewis (1984). If we apply any of these theories to SIMULTANEOUS, they will generate the result that this concept refers to the relativized property simultaneity, even if many users of the concept take sim- ultaneity to be absolute. 2 The concept–property distinction in truth theory: Alston’s constraint Undoubtedly, then, it is important to draw the general distinction between property concepts and properties themselves. What, though, is this meant to show us about truth? Arguably, the locus classicus for thought on this topic is the work of William Alston, who observes of the concept-property distinction that “discussions of truth are led seriously astray by neglecting it.”2 Alston brings out the relevance of the dis- tinction to theories of truth as follows3: 1 In what follows, I’ll use small caps to denote concepts and italics to denote properties (and for empha- sis). -

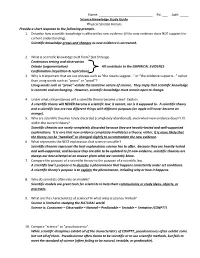

Ast#: ___Science Knowledge Study Guide Physical

Name: ______________________________ Pd: ___ Ast#: _____ Science Knowledge Study Guide Physical Science Honors Provide a short response to the following prompts. 1. Describe how scientific knowledge is affected by new evidence (if the new evidence does NOT support the current understanding). Scientific knowledge grows and changes as new evidence is uncovered. 2. What is scientific knowledge built from? (list 3 things) Continuous testing and observation Debate (argumentation) All contribute to the EMPIRICAL EVIDENCE Confirmation (repetition & replication) 3. Why is it important that we use phrases such as “the results suggest…” or “the evidence supports…” rather than using words such as “prove” or “proof”? Using words such as “prove” violate the tentative nature of science. They imply that scientific knowledge is concrete and unchanging. However, scientific knowledge must remain open to change. 4. Under what circumstances will a scientific theory become a law? Explain. A scientific theory will NEVER become a scientific law; it cannot, nor is it supposed to. A scientific theory and a scientific law are two different things with different purposes (an apple will never become an orange). 5. Why are scientific theories rarely discarded (completely abandoned), even when new evidence doesn’t fit within the current theory? Scientific theories are rarely completely discarded because they are heavily-tested and well-supported explanations. It is rare that new evidence completely invalidates a theory; rather, it is more likely that the theory can be “tweaked” or changed slightly to accommodate the new evidence. 6. What represents the BEST explanation that science can offer? Scientific theories represent the best explanations science has to offer. -

Greek and Latin Roots, Prefixes, and Suffixes

GREEK AND LATIN ROOTS, PREFIXES, AND SUFFIXES This is a resource pack that I put together for myself to teach roots, prefixes, and suffixes as part of a separate vocabulary class (short weekly sessions). It is a combination of helpful resources that I have found on the web as well as some tips of my own (such as the simple lesson plan). Lesson Plan Ideas ........................................................................................................... 3 Simple Lesson Plan for Word Study: ........................................................................... 3 Lesson Plan Idea 2 ...................................................................................................... 3 Background Information .................................................................................................. 5 Why Study Word Roots, Prefixes, and Suffixes? ......................................................... 6 Latin and Greek Word Elements .............................................................................. 6 Latin Roots, Prefixes, and Suffixes .......................................................................... 6 Root, Prefix, and Suffix Lists ........................................................................................... 8 List 1: MEGA root list ................................................................................................... 9 List 2: Roots, Prefixes, and Suffixes .......................................................................... 32 List 3: Prefix List ...................................................................................................... -

Aristotle's Economic Defence of Private Property

ECONOMIC HISTORY ARISTOTLE ’S ECONOMIC DEFENCE OF PRIVATE PROPERTY CONOR MCGLYNN Senior Sophister Are modern economic justifications of private property compatible with Aristotle’s views? Conor McGlynn deftly argues that despite differences, there is much common ground between Aristotle’s account and contemporary economic conceptions of private property. The paper explores the concepts of natural exchange and the tragedy of the commons in order to reconcile these divergent views. Introduction Property rights play a fundamental role in the structure of any economy. One of the first comprehensive defences of the private ownership of property was given by Aristotle. Aris - totle’s defence of private property rights, based on the role private property plays in pro - moting virtue, is often seen as incompatible with contemporary economic justifications of property, which are instead based on mostly utilitarian concerns dealing with efficiency. Aristotle defends private ownership only insofar as it plays a role in promoting virtue, while modern defenders appeal ultimately to the efficiency gains from private property. However, in spite of these fundamentally divergent views, there are a number of similar - ities between the defence of private property Aristotle gives and the account of private property provided by contemporary economics. I will argue that there is in fact a great deal of overlap between Aristotle’s account and the economic justification. While it is true that Aristotle’s theory is quite incompatible with a free market libertarian account of pri - vate property which defends the absolute and inalienable right of an individual to their property, his account is compatible with more moderate political and economic theories of private property. -

Two Problems for Resemblance Nominalism

Two Problems for Resemblance Nominalism Andrea C. Bottani, Università di Bergamo [email protected] I. Nominalisms Just as ‘being’ according to Aristotle, ‘nominalism’ can be said in many ways, being currently used to refer to a number of non equivalent theses, each denying the existence of entities of a certain sort. In a Quinean largely shared sense, nominalism is the thesis that abstract entities do not exist. In other senses, some of which also are broadly shared, nominalism is the thesis that universals do not exist; the thesis that neither universals nor tropes exist; the thesis that properties do not exist. These theses seem to be independent, at least to some degree: some ontologies incorporate all of them, some none, some just one and some more than one but not all. This makes the taxonomy of nominalisms very complex. Armstrong 1978 distinguishes six varieties of nominalism according to which neither universals nor tropes exist, called respectively ‘ostrich nominalism’, ‘predicate nominalism’, ‘concept nominalism’, ‘mereological nominalism’, ‘class nominalism’ and ‘resemblance nominalism’, which Armstrong criticizes but considers superior to any other version. According to resemblance nominalism, properties depend on primitive resemblance relations among particulars, while there are neither universals nor tropes. Rodriguez-Pereyra 2002 contains a systematic formulation and defence of a version of resemblance nominalism according to which properties exist, conceived of as maximal classes of exactly resembling particulars. An exact resemblance is one that two particulars can bear to each other just in case there is some ‘lowest determinate’ property - for example, being of an absolutely precise nuance of red – that both have just in virtue of precisely resembling certain particulars (so that chromatic resemblance can only be chromatic indiscernibility). -

Aristotle & Locke: Ancients and Moderns on Economic Theory & The

Xavier University Exhibit Honors Bachelor of Arts Undergraduate 2015-4 Aristotle & Locke: Ancients and Moderns on Economic Theory & the Best Regime Andrew John Del Bene Xavier University - Cincinnati Follow this and additional works at: http://www.exhibit.xavier.edu/hab Part of the Ancient History, Greek and Roman through Late Antiquity Commons, and the Ancient Philosophy Commons Recommended Citation Del Bene, Andrew John, "Aristotle & Locke: Ancients and Moderns on Economic Theory & the Best Regime" (2015). Honors Bachelor of Arts. Paper 9. http://www.exhibit.xavier.edu/hab/9 This Capstone/Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Undergraduate at Exhibit. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Bachelor of Arts by an authorized administrator of Exhibit. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Aristotle & Locke: Ancients and Moderns on Economic Theory & the Best Regime Andrew John Del Bene Honors Bachelor of Arts – Senior Thesis Project Director: Dr. Timothy Quinn Readers: Dr. Amit Sen & Dr. E. Paul Colella Course Director: Dr. Shannon Hogue I respectfully submit this thesis project as partial fulfillment for the Honors Bachelor of Arts Degree. I dedicate this project, and my last four years as an HAB at Xavier University, to my grandfather, John Francis Del Bene, who taught me that in life, you get out what you put in. Del Bene 1 Table of Contents Introduction — Philosophy and Economics, Ancients and Moderns 2 Chapter One — Aristotle: Politics 5 Community: the Household and the Πόλις 9 State: Economics and Education 16 Analytic Synthesis: Aristotle 26 Chapter Two — John Locke: The Two Treatises of Government 27 Community: the State of Nature and Civil Society 30 State: Economics and Education 40 Analytic Synthesis: Locke 48 Chapter Three — Aristotle v. -

HEGEL's JUSTIFICATION of PRIVATE PROPERTY Author(S): Alan Patten Source: History of Political Thought, Vol

Imprint Academic Ltd. HEGEL'S JUSTIFICATION OF PRIVATE PROPERTY Author(s): Alan Patten Source: History of Political Thought, Vol. 16, No. 4 (Winter 1995), pp. 576-600 Published by: Imprint Academic Ltd. Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/26215902 Accessed: 06-07-2018 14:30 UTC JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at http://about.jstor.org/terms Imprint Academic Ltd. is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to History of Political Thought This content downloaded from 128.112.70.201 on Fri, 06 Jul 2018 14:30:13 UTC All use subject to http://about.jstor.org/terms HEGEL'S JUSTIFICATION OF PRIVATE PROPERTY Alan Patten1 I Introduction Hegel subscribes to one of the oldest and most common justifications of private property in the history of political thought: the view that there is an intrinsic connection between private property and freedom. 'The true position', he asserts, 'is that, from the point of view of freedom, property, as the first existence of freedom, is an essential end for itself ? Because property gives 'existence' to freedom, it grounds a right (Recht) both in Hegel's technical sense of the term,3 and in the everyday sense that it imposes various duties and obligations, e.g.