The Computational Complexity Column by V

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fast Dynamic Programming on Graph Decompositions

Fast Dynamic Programming on Graph Decompositions∗ Johan M. M. van Rooij† Hans L. Bodlaender† Erik Jan van Leeuwen‡ Peter Rossmanith§ Martin Vatshelle‡ June 6, 2018 Abstract In this paper, we consider three types of graph decompositions, namely tree decompo- sitions, branch decompositions, and clique decompositions. We improve the running time of dynamic programming algorithms on these graph decompositions for a large number of problems as a function of the treewidth, branchwidth, or cliquewidth, respectively. Such algorithms have many practical and theoretical applications. On tree decompositions of width k, we improve the running time for Dominating Set to O∗(3k). Hereafter, we give a generalisation of this result to [ρ,σ]-domination problems with finite or cofinite ρ and σ. For these problems, we give O∗(sk)-time algorithms. Here, s is the number of ‘states’ a vertex can have in a standard dynamic programming algorithm for such a problems. Furthermore, we give an O∗(2k)-time algorithm for counting the number of perfect matchings in a graph, and generalise this result to O∗(2k)-time algorithms for many clique covering, packing, and partitioning problems. On branch decompositions of width k, we give ∗ ω k ∗ ω k an O (3 2 )-time algorithm for Dominating Set, an O (2 2 )-time algorithm for counting ∗ ω k the number of perfect matchings, and O (s 2 )-time algorithms for [ρ,σ]-domination problems involving s states with finite or cofinite ρ and σ. Finally, on clique decompositions of width k, we give O∗(4k)-time algorithms for Dominating Set, Independent Dominating Set, and Total Dominating Set. -

Total Domination on Some Graph Operators

mathematics Article Total Domination on Some Graph Operators José M. Sigarreta Faculty of Mathematics, Autonomous University of Guerrero, Carlos E. Adame 5, Col. La Garita, C. P. 39350 Acapulco, Mexico; [email protected]; Tel.: +52-744-159-2272 Abstract: Let G = (V, E) be a graph; a set D ⊆ V is a total dominating set if every vertex v 2 V has, at least, one neighbor in D. The total domination number gt(G) is the minimum cardinality among all total dominating sets. Given an arbitrary graph G, we consider some operators on this graph; S(G), R(G), and Q(G), and we give bounds or the exact value of the total domination number of these new graphs using some parameters in the original graph G. Keywords: domination theory; total domination; graph operators 1. Introduction The study of the mathematical and structural properties of operators in graphs was initiated in Reference [1]. This study is a current research topic, mainly because of its multiple theoretical and practical applications (see References [2–6]). Motivated by the previous investigations, we work here on the total domination number of some graph operators. Other important parameters have also been studied in this type of graphs (see References [7,8]). We denote by G = (V, E) a finite simple graph of order n = jVj and size m = jEj. For any two adjacent vertices u, v 2 V, uv denotes the corresponding edge, and we denote N(v) = fu 2 V : uv 2 Eg and N[v] = N(v) [ fvg. We denote by D, d the maximum and Citation: Sigarreta, J.M. -

Locating Domination in Bipartite Graphs and Their Complements

Locating domination in bipartite graphs and their complements C. Hernando∗ M. Moray I. M. Pelayoz Abstract A set S of vertices of a graph G is distinguishing if the sets of neighbors in S for every pair of vertices not in S are distinct. A locating-dominating set of G is a dominating distinguishing set. The location-domination number of G, λ(G), is the minimum cardinality of a locating-dominating set. In this work we study relationships between λ(G) and λ(G) for bipartite graphs. The main result is the characterization of all connected bipartite graphs G satisfying λ(G) = λ(G) + 1. To this aim, we define an edge-labeled graph GS associated with a distinguishing set S that turns out to be very helpful. Keywords: domination; location; distinguishing set; locating domination; complement graph; bipartite graph. AMS subject classification: 05C12, 05C35, 05C69. ∗Departament de Matem`atiques. Universitat Polit`ecnica de Catalunya, Barcelona, Spain, car- [email protected]. Partially supported by projects Gen. Cat. DGR 2017SGR1336 and MTM2015- arXiv:1711.01951v2 [math.CO] 18 Jul 2018 63791-R (MINECO/FEDER). yDepartament de Matem`atiques. Universitat Polit`ecnica de Catalunya, Barcelona, Spain, [email protected]. Partially supported by projects Gen. Cat. DGR 2017SGR1336, MTM2015-63791-R (MINECO/FEDER) and H2020-MSCA-RISE project 734922 - CONNECT. zDepartament de Matem`atiques. Universitat Polit`ecnica de Catalunya, Barcelona, Spain, ig- [email protected]. Partially supported by projects MINECO MTM2014-60127-P, igna- [email protected]. This project has received funding from the European Union's Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under the Marie Sk lodowska-Curie grant agreement No 734922. -

Dominating Cliques in Graphs

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Elsevier - Publisher Connector Discrete Mathematics 86 (1990) 101-116 101 North-Holland DOMINATING CLIQUES IN GRAPHS Margaret B. COZZENS Mathematics Department, Northeastern University, Boston, MA 02115, USA Laura L. KELLEHER Massachusetts Maritime Academy, USA Received 2 December 1988 A set of vertices is a dominating set in a graph if every vertex not in the dominating set is adjacent to one or more vertices in the dominating set. A dominating clique is a dominating set that induces a complete subgraph. Forbidden subgraph conditions sufficient to imply the existence of a dominating clique are given. For certain classes of graphs, a polynomial algorithm is given for finding a dominating clique. A forbidden subgraph characterization is given for a class of graphs that have a connected dominating set of size three. Introduction A set of vertices in a simple, undirected graph is a dominating set if every vertex in the graph which is not in the dominating set is adjacent to one or more vertices in the dominating set. The domination number of a graph G is the minimum number of vertices in a dominating set. Several types of dominating sets have been investigated, including independent dominating sets, total dominating sets, and connected dominating sets, each of which has a corresponding domination number. Dominating sets have applications in a variety of fields, including communication theory and political science. For more background on dominating sets see [3, 5, 151 and other articles in this issue. For arbitrary graphs, the problem of finding the size of a minimum dominating set in the graph is an NP-complete problem [9]. -

The Bidimensionality Theory and Its Algorithmic

The Bidimensionality Theory and Its Algorithmic Applications by MohammadTaghi Hajiaghayi B.S., Sharif University of Technology, 2000 M.S., University of Waterloo, 2001 Submitted to the Department of Mathematics in partial ful¯llment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY at the MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY June 2005 °c MohammadTaghi Hajiaghayi, 2005. All rights reserved. The author hereby grants to MIT permission to reproduce and distribute publicly paper and electronic copies of this thesis document in whole or in part. Author.............................................................. Department of Mathematics April 29, 2005 Certi¯ed by. Erik D. Demaine Associate Professor of Electrical Engineering and Computer Science Thesis Supervisor Accepted by . Rodolfo Ruben Rosales Chairman, Applied Mathematics Committee Accepted by . Pavel I. Etingof Chairman, Department Committee on Graduate Students 2 The Bidimensionality Theory and Its Algorithmic Applications by MohammadTaghi Hajiaghayi Submitted to the Department of Mathematics on April 29, 2005, in partial ful¯llment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Abstract Our newly developing theory of bidimensional graph problems provides general techniques for designing e±cient ¯xed-parameter algorithms and approximation algorithms for NP- hard graph problems in broad classes of graphs. This theory applies to graph problems that are bidimensional in the sense that (1) the solution value for the k £ k grid graph (and similar graphs) grows with k, typically as (k2), and (2) the solution value goes down when contracting edges and optionally when deleting edges. Examples of such problems include feedback vertex set, vertex cover, minimum maximal matching, face cover, a series of vertex- removal parameters, dominating set, edge dominating set, r-dominating set, connected dominating set, connected edge dominating set, connected r-dominating set, and unweighted TSP tour (a walk in the graph visiting all vertices). -

Combinatorial Optimization

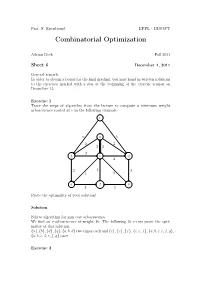

Prof. F. Eisenbrand EPFL - DISOPT Combinatorial Optimization Adrian Bock Fall 2011 Sheet 6 December 1, 2011 General remark: In order to obtain a bonus for the final grading, you may hand in written solutions to the exercises marked with a star at the beginning of the exercise session on December 13. Exercise 1 Trace the steps of algorithm from the lecture to compute a minimum weight arborescence rooted at r in the following example. r 6 a 5 2 2 2 2 2 b c d 4 2 1 3 1 2 e f g 1 3 Prove the optimality of your solution! Solution Follow algorithm for min cost arborescence. We find an r-arborescence of weight 16. The following 16 r-cuts prove the opti- mality of this solution: {a}, {b}, {d}, {g}, {a, b, d} two times each and {c}, {e}, {f}, {c, e, f}, {a,b,c,e,f,g}, {a,b,c,d,e,f,g} once. Exercise 2 Let G = (A ∪ B, E) be a bipartite graph. We define two partition matroids M1 =(E, I1) and M2 =(E, I2) with I1 = {I ⊆ E : |I ∩ δ(a)| ≤ 1 for all a ∈ A} and I2 = {I ⊆ E : |I ∩ δ(b)| ≤ 1 for all b ∈ B}. What is a set I ∈ I1 ∩ I2 in terms of graph theory? Can you maximize a weight function w : E → R over the intersection? Remark: This is a special case of the optimization over the intersection of two matroids. It can be shown that all such matroid intersection problems can be solved efficiently. -

Polynomial-Time Data Reduction for Dominating Set∗

Journal of the ACM, Vol. 51(3), pp. 363–384, 2004 Polynomial-Time Data Reduction for Dominating Set∗ Jochen Alber† Michael R. Fellows‡ Rolf Niedermeier§ Abstract Dealing with the NP-complete Dominating Set problem on graphs, we demonstrate the power of data reduction by preprocessing from a theoretical as well as a practical side. In particular, we prove that Dominating Set restricted to planar graphs has a so-called problem kernel of linear size, achieved by two simple and easy to implement reduction rules. Moreover, having implemented our reduction rules, first experiments indicate the impressive practical potential of these rules. Thus, this work seems to open up a new and prospective way how to cope with one of the most important problems in graph theory and combinatorial optimization. 1 Introduction Motivation. A core tool for practically solving NP-hard problems is data reduction through preprocessing. Weihe [40, 41] gave a striking example when dealing with the NP-complete Red/Blue Dominating Set problem appearing in the context of the European railroad network. In a preprocess- ing phase, he applied two simple data reduction rules again and again until ∗An extended abstract of this work entitled “Efficient Data Reduction for Dominating Set: A Linear Problem Kernel for the Planar Case” appeared in the Proceedings of the 8th Scandinavian Workshop on Algorithm Theory (SWAT 2002), Lecture Notes in Computer Science (LNCS) 2368, pages 150–159, Springer-Verlag 2002. †Wilhelm-Schickard-Institut f¨ur Informatik, Universit¨at T¨ubingen, Sand 13, D- 72076 T¨ubingen, Fed. Rep. of Germany. Email: [email protected]. -

Upper Dominating Set: Tight Algorithms for Pathwidth and Sub-Exponential Approximation

Upper Dominating Set: Tight Algorithms for Pathwidth and Sub-Exponential Approximation Louis Dublois1, Michael Lampis1, and Vangelis Th. Paschos1 Universit´eParis-Dauphine, PSL University, CNRS, LAMSADE, Paris, France flouis.dublois,michail.lampis,[email protected] Abstract. An upper dominating set is a minimal dominating set in a graph. In the Upper Dominating Set problem, the goal is to find an upper dominating set of maximum size. We study the complexity of parameterized algorithms for Upper Dominating Set, as well as its sub-exponential approximation. First, we prove that, under ETH, k- cannot be solved in time O(no(k)) (improving Upper Dominatingp Set on O(no( k))), and in the same time we show under the same complex- ity assumption that for any constant ratio r and any " > 0, there is no 1−" r-approximation algorithm running in time O(nk ). Then, we settle the problem's complexity parameterized by pathwidth by giving an al- gorithm running in time O∗(6pw) (improving the current best O∗(7pw)), and a lower bound showing that our algorithm is the best we can get under the SETH. Furthermore, we obtain a simple sub-exponential ap- proximation algorithm for this problem: an algorithm that produces an r-approximation in time nO(n=r), for any desired approximation ratio r < n. We finally show that this time-approximation trade-off is tight, up to an arbitrarily small constant in the second exponent: under the randomized ETH, and for any ratio r > 1 and " > 0, no algorithm 1−" can output an r-approximation in time n(n=r) . -

PERFECT DOMINATING SETS Ý Marilynn Livingston£ Quentin F

In Congressus Numerantium 79 (1990), pp. 187-203. PERFECT DOMINATING SETS Ý Marilynn Livingston£ Quentin F. Stout Department of Computer Science Elec. Eng. and Computer Science Southern Illinois University University of Michigan Edwardsville, IL 62026-1653 Ann Arbor, MI 48109-2122 Abstract G G A dominating set Ë of a graph is perfect if each vertex of is dominated by exactly one vertex in Ë . We study the existence and construction of PDSs in families of graphs arising from the interconnection networks of parallel computers. These include trees, dags, series-parallel graphs, meshes, tori, hypercubes, cube-connected cycles, cube-connected paths, and de Bruijn graphs. For trees, dags, and series-parallel graphs we give linear time algorithms that determine if a PDS exists, and generate a PDS when one does. For 2- and 3-dimensional meshes, 2-dimensional tori, hypercubes, and cube-connected paths we completely characterize which graphs have a PDS, and the structure of all PDSs. For higher dimensional meshes and tori, cube-connected cycles, and de Bruijn graphs, we show the existence of a PDS in infinitely many cases, but our characterization d is not complete. Our results include distance d-domination for arbitrary . 1 Introduction = ´Î; Eµ Î E i Suppose G is a graph with vertex set and edge set . A vertex is said to dominate a E i j i = j Ë Î vertex j if contains an edge from to or if . A set of vertices is called a dominating G Ë G set of G if every vertex of is dominated by at least one member of . -

On Combinatorial Optimization for Dominating Sets (Literature Survey, New Models)

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/344114217 On combinatorial optimization for dominating sets (literature survey, new models) Preprint · September 2020 DOI: 10.13140/RG.2.2.34919.68006 CITATIONS 0 1 author: Mark Sh. Levin Russian Academy of Sciences 193 PUBLICATIONS 1,004 CITATIONS SEE PROFILE Some of the authors of this publication are also working on these related projects: Scheduling View project All content following this page was uploaded by Mark Sh. Levin on 04 September 2020. The user has requested enhancement of the downloaded file. 1 On combinatorial optimization for dominating sets (literature survey, new models) Mark Sh. Levin The paper focuses on some versions of connected dominating set problems: basic problems and multi- criteria problems. A literature survey on basic problem formulations and solving approaches is presented. The basic connected dominating set problems are illustrated by simplified numerical examples. New integer programming formulations of dominating set problems (with multiset estimates) are suggested. Keywords: combinatorial optimization, connected dominating sets, multicriteria decision making, solving strategy, heuristics, networking, multiset 1. Introduction In recent decades, the significance of the connected dominating set problem has been increased (e.g., [43,60,62,66,124,149]). This problem consists in searching for the minimum sized connected dominating set for the initial graph (e.g., [43,60,62,66]). Main applications of the problems of this kind are pointed out in Table 1. Table 1. Basic application domains of dominating set problems No. Application domain Source(s) 1. Communication networks (e.g., design of virtual backbone in mobile networks, [16,30,43,48,68,108] connected dominating set based index scheme in WSNs) [116,121,141,149] 2. -

![Arxiv:1911.08964V5 [Cs.DS] 26 Apr 2021 Ewe Orsadr Rbes D Problems: Standard Four Between Ta.(09 Hwdta H Rbe Splnma-Iesol Polynomial-Time Respectively](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/3457/arxiv-1911-08964v5-cs-ds-26-apr-2021-ewe-orsadr-rbes-d-problems-standard-four-between-ta-09-hwdta-h-rbe-splnma-iesol-polynomial-time-respectively-2293457.webp)

Arxiv:1911.08964V5 [Cs.DS] 26 Apr 2021 Ewe Orsadr Rbes D Problems: Standard Four Between Ta.(09 Hwdta H Rbe Splnma-Iesol Polynomial-Time Respectively

Discrete Mathematics and Theoretical Computer Science DMTCS vol. 23:1, 2021, #10 New Algorithms for Mixed Dominating Set Louis Dublois Michael Lampis Vangelis Th. Paschos Universit´eParis-Dauphine, PSL University, CNRS, LAMSADE, Paris, France received 5th Oct. 2020, revised 13th Jan. 2021, 15th Apr. 2021, accepted 16th Apr. 2021. A mixed dominating set is a set of vertices and edges that dominates all vertices and edges of a graph. We study the complexity of exact and parameterized algorithms for MIXED DOMINATING SET, resolving some open questions. In particular, we settle the problem’s complexity parameterized by treewidth and pathwidth by giving an algorithm ∗ ∗ running in time O (5tw) (improving the current best O (6tw)), and a lower bound showing that our algorithm cannot be improved under the Strong Exponential Time Hypothesis (SETH), even if parameterized by pathwidth ∗ (improving a lower bound of O ((2 − ε)pw)). Furthermore, by using a simple but so far overlooked observation on the structure of minimal solutions, we obtain branching algorithms which improve the best known FPT algorithm for this problem, from O∗(4.172k ) to O∗(3.510k), and the best known exact algorithm, from O∗(2n) and exponential ∗ space, to O (1.912n) and polynomial space. Keywords: FPT Algorithms, Exact Algorithms, Mixed Domination 1 Introduction Domination problems in graphs are one of the most well-studied topics in theoretical computer science. In this paper we study a variant called MIXED DOMINATING SET: we are given a graph G = (V, E) and are asked to select D ⊆ V and M ⊆ E such that |D ∪ M| is minimized and the set D ∪ M dominates V ∪ E, where a vertex dominates itself, its neighbors, and its incident edges and an edge dominates itself, its endpoints, and all edges with which it shares an endpoint. -

A Gentle Introduction to Computational Complexity Theory, and a Little Bit More

A GENTLE INTRODUCTION TO COMPUTATIONAL COMPLEXITY THEORY, AND A LITTLE BIT MORE SEAN HOGAN Abstract. We give the interested reader a gentle introduction to computa- tional complexity theory, by providing and looking at the background leading up to a discussion of the complexity classes P and NP. We also introduce NP-complete problems, and prove the Cook-Levin theorem, which shows such problems exist. We hope to show that study of NP-complete problems is vi- tal to countless algorithms that help form a bridge between theoretical and applied areas of computer science and mathematics. Contents 1. Introduction 1 2. Some basic notions of algorithmic analysis 2 3. The boolean satisfiability problem, SAT 4 4. The complexity classes P and NP, and reductions 8 5. The Cook-Levin Theorem (NP-completeness) 10 6. Valiant's Algebraic Complexity Classes 13 Appendix A. Propositional logic 17 Appendix B. Graph theory 17 Acknowledgments 18 References 18 1. Introduction In \computational complexity theory", intuitively the \computational" part means problems that can be modeled and solved by a computer. The \complexity" part means that this area studies how much of some resource (time, space, etc.) a problem takes up when being solved. We will focus on the resource of time for the majority of the paper. The motivation of this paper comes from the author noticing that concepts from computational complexity theory seem to be thrown around often in casual discus- sions, though poorly understood. We set out to clearly explain the fundamental concepts in the field, hoping to both enlighten the audience and spark interest in further study in the subject.