Contents Volume 7 Number 4 / May 2014

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Event Winners

Meet History -- NCAA Division I Outdoor Championships Event Winners as of 6/17/2017 4:40:39 PM Men's 100m/100yd Dash 100 Meters 100 Meters 1992 Olapade ADENIKEN SR 22y 292d 10.09 (2.0) +0.09 2017 Christian COLEMAN JR 21y 95.7653 10.04 (-2.1) +0.08 UTEP {3} Austin, Texas Tennessee {6} Eugene, Ore. 1991 Frank FREDERICKS SR 23y 243d 10.03w (5.3) +0.00 2016 Jarrion LAWSON SR 22y 36.7652 10.22 (-2.3) +0.01 BYU Eugene, Ore. Arkansas Eugene, Ore. 1990 Leroy BURRELL SR 23y 102d 9.94w (2.2) +0.25 2015 Andre DE GRASSE JR 20y 215d 9.75w (2.7) +0.13 Houston {4} Durham, N.C. Southern California {8} Eugene, Ore. 1989 Raymond STEWART** SR 24y 78d 9.97w (2.4) +0.12 2014 Trayvon BROMELL FR 18y 339d 9.97 (1.8) +0.05 TCU {2} Provo, Utah Baylor WJR, AJR Eugene, Ore. 1988 Joe DELOACH JR 20y 366d 10.03 (0.4) +0.07 2013 Charles SILMON SR 21y 339d 9.89w (3.2) +0.02 Houston {3} Eugene, Ore. TCU {3} Eugene, Ore. 1987 Raymond STEWART SO 22y 80d 10.14 (0.8) +0.07 2012 Andrew RILEY SR 23y 276d 10.28 (-2.3) +0.00 TCU Baton Rouge, La. Illinois {5} Des Moines, Iowa 1986 Lee MCRAE SO 20y 136d 10.11 (1.4) +0.03 2011 Ngoni MAKUSHA SR 24y 92d 9.89 (1.3) +0.08 Pittsburgh Indianapolis, Ind. Florida State {3} Des Moines, Iowa 1985 Terry SCOTT JR 20y 344d 10.02w (2.9) +0.02 2010 Jeff DEMPS SO 20y 155d 9.96w (2.5) +0.13 Tennessee {3} Austin, Texas Florida {2} Eugene, Ore. -

THE NCAA NEWS STAFF Oversight of Institutions’ Com- Schools Comply

Official Publication of the National Collegiate Athletic Association June 9, 1993, Volume 30, Number 23 States growing more involved in gender equity By Ronald D. Mott duced hills that call for more strict up to the states to see that those California coordinator, said in the Hart, a Democrat from Santa Bar- THE NCAA NEWS STAFF oversight of institutions’ com- schools comply. publication American Volleyhall. bara, introduced Senate Bill 262 in pliance with Title IX and current “Just because it has been the prac- February. It would amend Califor- NOW filed suits In the belief that high schools state gender-equity laws. The bill tice in rhe past does not make it nia’s existing Education Code to and junior and senior colleges- in Florida, House Bill X99, was The National Organization for justifiable forever.” require that institutions in the including NCAA institutions-are signed into law last month. Women (NOW) demanded in two The lawsuits were filed in San California State IJniversity system not doing enough Lo comply with These legislative actions are lawsuits it filed against the Califor- Francisco Superior Court against achieve frmale/male intercollegi- Title IX, more and more state what many believe are only a pre- nia State University system thar the the entire system and in Santa ate athletics participation reflect- legislatures are beginning to insert lude to what will happen across the system spend equal funds on wom- (Iara Superior Courf against San ing the ratio of female to male themselves into the gender-equity country. Some state legislators es- en’s sports and men’s sports. -

Outdoor Track and Field DIVISION I

DIVISION I 103 Outdoor Track and Field DIVISION I 2001 Championships OUTDOOR TRACK Highlights Volunteers Are Victorious: Tennessee used a strong performance from its sprinters to edge TCU by a point May 30-June 2 at Oregon. The Volunteers earned their third title with 50 points, as the championship-clinching point was scored by the 1,600-meter relay team in the final event of the meet. Knowing it only had to finish the event to secure the point to break the tie with TCU, Tennessee’s unit passed the baton careful- ly and placed eighth. Justin Gatlin played the key role in getting Tennessee into position to win by capturing the 100- and 200-meter dashes. Gatlin was the meet’s only individual double winner. Sean Lambert supported Gatlin’s effort by finishing fourth in the 100. His position was another important factor in Tennessee’s victory, as he placed just ahead of a pair of TCU competitors. Gatlin and Lambert composed half of the Volunteers’ 400-meter relay team that was second. TCU was led by Darvis Patton, who was third in the 200, fourth in the long jump and sixth in the 100. He also was a member of the Horned Frogs’ victorious 400-meter relay team. TEAM STANDINGS 1. Tennessee ..................... 50 Colorado St. ................. 10 Missouri........................ 4 2. TCU.............................. 49 Mississippi .................... 10 N.C. A&T ..................... 4 3. Baylor........................... 361/2 28. Florida .......................... 9 Northwestern St. ........... 4 4. Stanford........................ 36 29. Idaho St. ...................... 8 Purdue .......................... 4 5. LSU .............................. 32 30. Minnesota ..................... 7 Southern Miss. .............. 4 6. Alabama...................... -

Contractor License Hy-Tek's MEET MANAGER 10:57 AM 5/8/2019

Flash Results, Inc. - Contractor License Hy-Tek's MEET MANAGER 10:57 AM 5/8/2019 Page 1 SEC Outdoor Championships - 5/9/2019 to 5/11/2019 John McDonnell Field Hosted by University of Arkansas Meet Program Event 21 Men 100 M Event 22 Men 200 M 9 Advance: Top 1 Each Heat plus Next 5 Best Times 9 Advance: Top 1 Each Heat plus Next 4 Best Times Friday 5/10/2019 - 8:10 PM Thursday 5/9/2019 - 7:10 PM Collegiate: 9.82 6/7/2017 Christian Coleman Collegiate: 19.69 5/26/2007 Walter Dix SEC Meet: 9.93 2008 Richard Thompson SEC Meet: 19.86 2002 Justin Gatlin Facility: 9.97 2008 Richard Thompson Facility: 19.87 2007 Wallace Spearmon, Jr. Lane Name Yr School Seed Time Lane Name Yr School Seed Time Heat 1 of 4 Prelims Heat 1 of 5 Prelims 2 Karson Kowalchuk JR Miss State 10.35 _________ 2 Okheme Moore FR Miss State 21.05 _________ 3 Elijah Miller SO Tennessee 10.48 _________ 3 Jaron Flournoy SR LSU 20.13 _________ 4 Raymond Ekevwo JR Florida 10.12 _________ 4 Mustaqeem Williams SR Tennessee 20.70 _________ 5 Carlos Wilson SO South Caroli 10.67 _________ 5 Dwight St Hillaire SO Kentucky 20.76 _________ 6 Joshua Burks SR Auburn 10.77 _________ 6 Evan Miller FR South Caroli NT _________ 7 Mustaqeem Williams SR Tennessee 10.22 _________ 7 Jason Reese FR Auburn 21.52 _________ 8 Ryan Clark SR Florida 10.30 _________ 8 Shaun Shivers FR Auburn 21.00 _________ 9 Shaun Shivers FR Auburn 10.44 _________ 9 Jeffrey Uzzell SO Tennessee 21.55 _________ Heat 2 of 4 Prelims Heat 2 of 5 Prelims 2 Darrell Singleton JR South Caroli 10.23 _________ 2 Jordan Sessom FR South -

Outdoor Track and Field DIVISION I MEN’S

Outdoor Track and Field DIVISION I MEN’S Highlights Oregon sets meet record with 88 points to win fi rst NCAA team title since 1984 -- Track Town is title town. Fueled by three individual national champions June 14, Oregon won its fi rst team title at the NCAA Division I Outdoor Track and Field Championships since 1984. The Ducks needed 24 points entering the day to secure the title after winning the NCAA indoor title earlier in the year, and got all that and more with wins from Mac Fleet in the 1,500 meters, Sam Crouser in the javelin and Devon Allen in the 110 hurdles. Tanguy Pepiot (steeplechase) and Arthur Delaney (200) also scored for Oregon, which put up 88 points, a meet record under the current scoring format. Florida was second with 70, after collecting three event titles of its own June 14 at Hayward Field. Oregon’s margin of victory was the largest at the meet since 1994. “If you would have told me at the beginning of the year that 70 points would not have won the NCAA championship, I would have been like, you’re crazy,” Oregon head coach Robert Johnson said. The three individual champions followed Edward Cheserek’s win in the 10,000 meters June 11. In between, the Ducks augmented their score with points elsewhere, includ- ing a 2-3-4 fi nish in the 5,000 June 13 that embodied the team’s “strength in numbers” mantra. “It’s a really special group of guys, a really close team,” Fleet said. -

CIF State Track & Field Championships

SPECTRUMNEWS1.COM @SPECTRUMNEWS1SOCAL @SPECNEWS1SOCAL CIFProgramAd_2019_R2.indd 1 1/17/19 5:03 PM 2019 CIF STATE TRACK & FIELD CHAMPIONSHIPS May 24-25 Veterans Memorial Stadium Buchanan HS, Clovis Table of Contents Pursuing Victory With Honorsm ……………………5 Girls Long Jump/Girls Triple Jump ……………… 45 CIF Executive Committee/Federated Council ……7 Girls Shot Put/Girls Discus Throw ……………… 47 Advisory Committee/State Office Staff ……………9 Boys High Jump/Boys Pole Vault ……………… 49 2019 Schedule ………………………………… 11 Boys Long Jump/Boys Triple Jump …………… 51 2019 Meet Preview …………………………… 13-21 Boys Shot Put/Boys Discus Throw ……………… 53 Girls/Boys 4x100M Relay …………………… 23-25 Wheelchair/Ambulatory Shot Put/400M Dash … 53 Girls/Boys 1600M Run ………………………… 27 Girls/Boys 3200M Run ………………………… 55 Girls 100M Hurdles/Boys 110M Hurdles …… 27-29 Wheelchair/Ambulatory 100M Dash/200M Dash … 55 Girls/Boys 400M Dash…………………………… 29 CIF State Track & Field Championship Records … 57 Girls/Boys 100M Dash…………………………… 31 U.S. National High School Records …………… 59 Girls/Boys 800M Run ………………………… 31-33 Boys State Track & Field Team Champions … 61-62 Girls/Boys 300M Hurdles ……………………… 33 Girls State Track & Field Team Champions ……… 63 Girls/Boys 200M Dash…………………………… 35 State Track & Field Individual Champions …… 64-73 Girls/Boys 4X400M Relay …………………… 37-41 State Track & Field Multiple Championships …… 74 Girls High Jump/Girls Pole Vault ……………… 43 2019 STATE TRACK & FIELD CHAMPIONSHIPS 3 Pursuing Victory With Honorsm The CIF was formed, and had its athletics. Kids participate in sports humble beginning, during the because it’s fun and the athletic 1914-1915 school year with only fields and gymnasium classrooms 65,927 high school students in our schools provide gives adults California; it has been estimated the opportunity to teach valu- that less than 8,000 students were able lessons that might not be participating on their high school learned in any other environment. -

Outdoor Track and Field DIVISION I Men’S

Outdoor Track and Field DIVISION I MEN’S Highlights Aggies emerge from men’s track pack for first crown: The term “4x1” nearly took on new meaning at the Division I Men’s Outdoor Track and Field Championships, as the final event offered the possibility that four teams could tie for the team title. Texas A&M made the most of the opportunity and won its first national championship in the sport June 13 in Fayetteville, Arkansas. The term “4x1” normally refers to the 400-meter relay, but the title actually was decided in the meet-ending 1,600-meter relay, where the Aggies finally caught Oregon and held off two other rivals to spoil those teams’ title hopes. The win clinched a rare double victory since Texas A&M had captured the women’s track and field title moments earlier. “We’re the national champions,” said Justin Oliver, who anchored the Aggies to a second-place finish in the 1,600-meter relay to lock up the title. “Texas A&M, no one else. That’s all I could say when I finished the race. We did it! We did it!” Oliver is a member of coach Pat Henry’s first graduating class, which brought the former LSU coach – who led the Tigers to three men’s and 12 women’s national track and field titles – his first crowns in five seasons at Texas A&M. “We’re extremely pleased. My staff worked very hard, and this is a very gratifying pair of championships for this team,” Henry said. -

1 Updated 16 August 2015

Updated 16 August 2015 1 FOREWORD In 1965, Rick Smith, then a sports writer with the San Diego Evening Tribune, gathered together all of the records he could find and produced the first San Diego/Imperial Valley Track Record Book. All of the events on the track were in yards. There were no girls’ marks because there was no girls’ high school track. There were events like 180-yard low hurdles, 220-yard dash on the straight-away and a one-turn 440. He produced the book again in 1971 and not until Steve Brand of the San Diego Union in 1993 published a completely updated book, listing both yards and meters, a complete girls list and a complete list of San Diego Section state champions, was it even attempted. Local track fans got yearly updates with not only all-time marks, but a list of the top 25 competitors from the year before through 2012. And, it was distributed through the schools without any cost. When funding in the form of advertising dried up, it resulted in the Track Book ceasing to be published but each year the marks were compiled in hopes the next year it would reappear. With no one stepping forth with the approximate $7,500 needed to defray those costs, and with the internet such a handy resource, it was agreed that this year the 2016 Track Guide (because it contains the top marks from 2015 as well as the all-time list) would go modern, appearing in the popular Track Magazine run by George Green. -

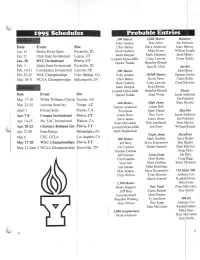

Probable Entries

Probable Entries 100 Meters 5,000 Meters Hammer Felix Andam Dan Alder Jim Edwards Date Event Site Chris Bailey Dave Anderson Marc Harisay Jan. 14 Snake River Open Pocatello, ID Mark Godfrey Mike Evans William Knight Mark Morgan Mark Johansen Jared Mabey Jan. 21 Utah State Invitational Logan, UT Leonard Myles-Mills Craig Lawson Corey Neddo Jan. 28 BYU Invitational Provo, UT Horace Tisdale Brandon Rhoads Feb. 4 Idaho State Invitational Pocatello. ID Sam St. Clair Javelin Feb. 10-11 Cornhusker Invitational Lincoln, NE 200 Meters John Home Feb. 23-25 WAC Championships Colo. Springs, CO Felix Andam 10,000 Meters SpencerJenson Mar. 10-11 NCAA Championships Indianapolis. IN Chris Bailey Kevin Ferre Curtis Keller Mark Godfrey Craig Lawson Chad Knowles Ou Mark Morgan Ryan Stroud Leonard Myles-Mills Brandon Rhoads Discus Date Event Site Horace Tisdale Chad Wood Jason Andersen Mar. 17-18 Willie Williams Classic Tucson, AZ Jim Freeland 400 Meters High Jump Marc Harisay Mar. 23-25 Arizona State Inv. Tempe, AZ Garrett Anderson Aaron Bell April 1 Fresno State Fresno. CA Tom Bean Marc Chenn Shot Put Apr. 7-8 Cougar Invitational Provo, UT James Beers Eric Crow Jason Andersen Steve James Lance Greer Jim Freeland Apr. 14-15 Mt. SAC Invitational Walnut. CA Peter McConkie Erik Lundmark Marc Harisay Apr. 20-22 Clarence Robison Inv. Provo, UT Leonard Myles-Mills Jon Parry William Knight Apr. 27-29 Penn Relays Philadelphia, PA Mark Stephenson Triple Jump Decathlon May 6 USC. UCLA Los Angeles, CA 800 Meters Mark Godfrey Steve Bulpitt May 17-20 WAC Championships Provo, UT Jeff Bray Slava Kouznetsov Ben Higbee May 31-June 3 NCAA Championships Knoxville, TN J.R. -

Gatorade® National Boys Track & Field Athlete of the Year

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Contact: Kelsey Rhoney (312-729-3685) GATORADE® NATIONAL BOYS TRACK & FIELD ATHLETE OF THE YEAR: ANTHONY SCHWARTZ Miami Dolphins First-Round Draft Pick Minkah Fitzpatrick Surprises Winner with Honor Plantation, FL. (June 28, 2018) – In its 33rd year of honoring the nation’s best high school athletes, The Gatorade Company today announced Anthony Schwartz of American Heritage School (Plantation, FL) as its 2017-18 Gatorade National Boys Track & Field Athlete of the Year. Schwartz was surprised with the news by Miami Dolphins 2018 First-Round Draft Pick Minkah Fitzpatrick. Check out the surprise video here. “One of the most gifted high school sprinters in history, Anthony repeatedly rose to the occasion against elite competition,” said Erik Boal, an editor for Dyestat.com. “His showcase in the 100, 200 and 4x100 relay at the Florida 2A state final cemented his legacy alongside [former national Gatorade winner] Trayvon Bromell, [former Gatorade state winner] Jeff Demps and [five- time state champion] Marvin Bracy as the most talented all-time Florida prep sprinters. Schwartz also gave us a preview of what the future holds by winning the USATF Juniors title in the 100 against several impressive collegiate freshmen.” The award, which recognizes not only outstanding athletic excellence, but also high standards of academic achievement and exemplary character demonstrated on and off the field, distinguishes Schwartz as the nation’s best male high school track & field athlete. A national advisory panel comprised of sport-specific experts and sports journalists helped select Schwartz from nearly 375,000 high school track & field athletes nationwide. -

Crystal Reports Activex Designer

Branch Sports Technology - Contractor License Hy-Tek's MEET MANAGER 7:11 PM 5/8/2013 Page 1 SEC Outdoor Championships - 5/9/2013 to 5/12/2013 Hosted by the University of Missouri Walton Stadium - Columbia, MO Meet Program - Saturday Flight 2 of 2 Finals Event 40 Men Javelin Throw 1 Malcolm Pennix SR Missouri Saturday 5/11/2013 - 1:00 PM 2 Jarrion Lawson FR Arkansas Top 9 marks advance to final 3 Anthony May JR Arkansas Collegiate: 89.10m 3/24/1990 Patrik Boden 4 Kamal Fuller JR Alabama SEC Meet: 79.65m 2009 Chris Hill 5 Tarik Batchelor SR Arkansas Facility: 75.98m 2002 Scott Russell 6 Marquis Dendy SO Florida PosNameYr School Seed Mark 7 Damar Forbes SR LSU Flight 1 of 2 Finals 8 Maicel Uibo FR Georgia 1 Tyler Kennedy SR Auburn 9 Jarrod Hutchen SR South Caroli 2 Joshua Suttmeier SO South Caroli 3 Kevin Shannon FR Alabama Event 18 Women Discus Throw 4 Jeremy Tuttle SO LSU Saturday 5/11/2013 - 2:30 PM 5 Philip LeBlanc JR LSU Top 9 marks advance to final 6 Jace Owens FR Auburn Collegiate: 67.48m 4/26/1981 Meg Richie Flight 2 of 2 Finals SEC Meet: 59.23m 1994 Danyel Mitchell 1 Jeff Woods SR Arkansas Facility: 57.94m 2012 Gia Lewis-Smallwood 2 Kyle Quinn FR Tennessee PosNameYr School Seed Mark 3 Raymond Dykstra SO Kentucky Flight 1 of 2 Finals 4 Piotr Antosik FR Miss State 1 Hilenn James JR Georgia 5 Devin Bogert SO Texas A&M 2 Megan Rayford SO Miss State 6 Ben Lapane JR Mississippi 3 Jill Hydrick JR Texas A&M 7 Sam Humphreys SR Texas A&M 4 Jessie Harrison SR Tennessee 8 Garrett Scantling SO Georgia 5 Cassie Wertman FR Tennessee 9 MaCauley -

2021 Sec Men's Indoor Track & Field Record Book

2021 SEC MEN’S INDOOR TRACK & FIELD RECORD BOOK All-Time SEC Team Champions 2001 Arkansas 108 Lexington, Ky. Year Champion Pts Site 2002 Arkansas 137 Fayetteville, Ark. 1957 LSU 44 Montgomery, Ala. 2003 Arkansas 120 Gainesville, Fla. 1958 Alabama 23.5 Montgomery, Ala. 2004 Florida 132 Lexington, Ky. 1959 Alabama 21 Montgomery, Ala. 2005 Arkansas 155 Fayetteville, Ark. 1960 Kentucky 20 Montgomery, Ala. 2006 Arkansas 141 Gainesville, Fla. 1961 Alabama 23.5 Montgomery, Ala. 2007 Arkansas 126 Lexington, Ky. 1962 Alabama 24 Montgomery, Ala. 2008 Arkansas 124 Fayetteville, Ark. 1963 LSU 30 Montgomery, Ala. 2009 Arkansas 130 Lexington, Ky. 1964 Tennessee 41 Montgomery, Ala. 2010 Arkansas 123 Fayetteville, Ark. 1965 Tennessee 50 Montgomery, Ala. 2011 Florida 148 Fayetteville, Ark. 1966 Tennessee 42 Montgomery, Ala. 2012 Arkansas 151 Lexington, Ky. 1967 Tennessee 58 Montgomery, Ala. 2013 Arkansas 152.5 Fayetteville, Ark. 1968 Tennessee 75 Montgomery, Ala. 2014 Arkansas 121 College Station, Texas 1969 Tennessee 111 Montgomery, Ala. 2015 Florida 114 Lexington, Ky. 1970 Tennessee 92.5 Montgomery, Ala. 2016 Arkansas 109 Fayetteville, Ark. 1971 Tennessee 80 Montgomery, Ala. 2017 Arkansas 98 Nashville, Tenn. 1972 Alabama 63 Montgomery, Ala. 2018 Alabama 91 College Station, Texas 1973 Tennessee 80 Jackson, Miss. 2019 Florida 103 Fayetteville, Ark. 1974 Tennessee 69 Montgomery, Ala. 2020 Arkansas 106 College Station, Texas 1975 Florida 63.5 Baton Rouge, La. 1976 Florida 60 Baton Rouge, La. Note: From 1957-62 the SEC Indoor Track Champion was decided 1977 Auburn 57 Baton Rouge, La. at the Garrett Coliseum Relays. In 1958, 1959, 1960 and 1962 a 1978 Auburn 149 Montgomery, Ala.