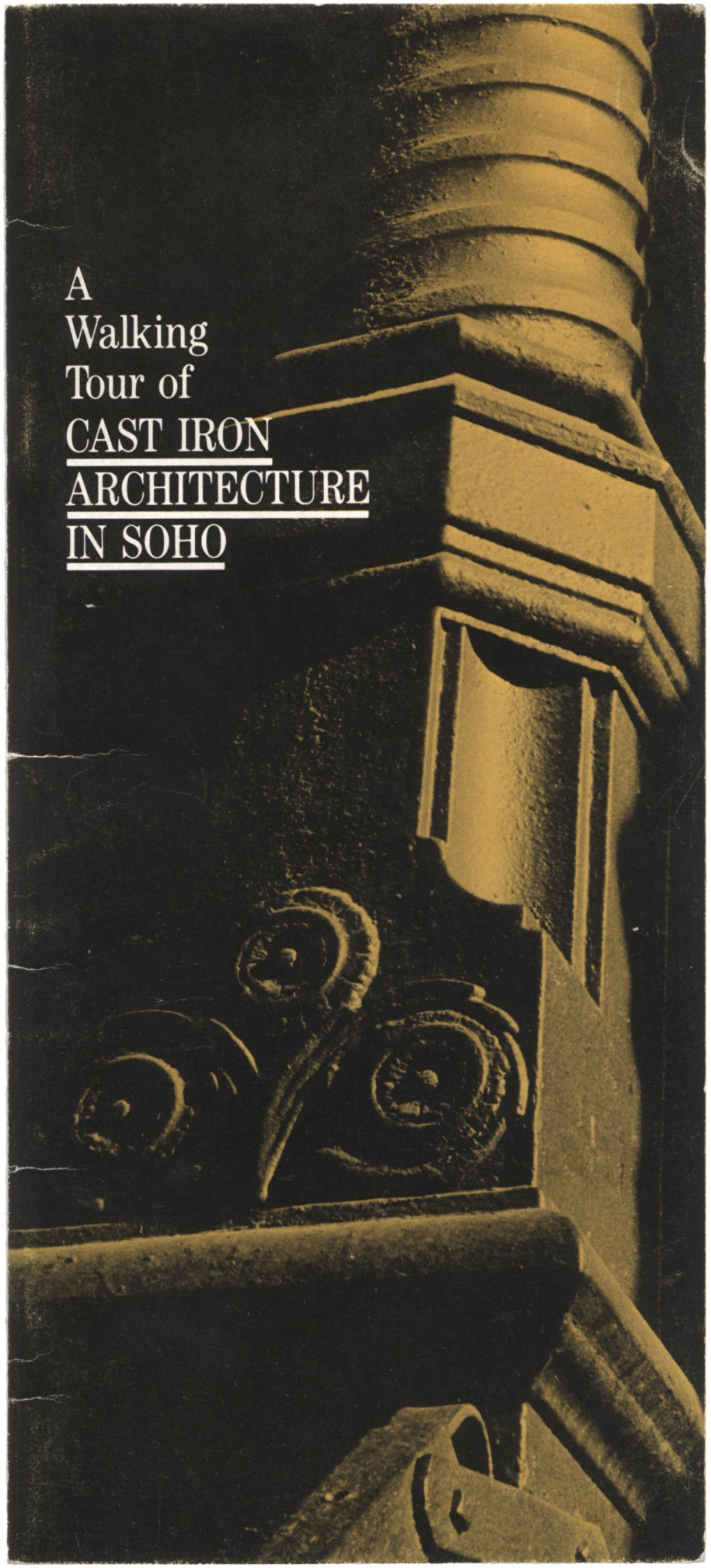

Architecture in Soho "

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Daisun Cohn-Williams- Acting Resume

Daisun Cohn-Williams SAG - AFTRA Hair: Black Eyes: Brown FILM The Sanctuary Lead Dir: Marc Rosenzweig Saviors Lead Dir: Daniel Russell Anatomy of the Moment Lead Dir: Berman Fenelus For the Love of Gauguin Lead Dir: Yana Bille Psycho Brother-In-law Supporting Dir: Jose Montesinos/Lifetime Tell Me How I Die Supporting Dir: DJ Viola LAPS Supporting Dir. Chad Diez All About the Money Supporting Dir: Kelby Joseph Pharmacopoeia Supporting Dir: Shannon Green Band-Aid Supporting Dir: Justin Chandra TV Ex Pats Series Lead Dir: Abe Heisler The New Adult Reoccurring Dir: Katherine Murray-Satchell This Indie Thing Reoccurring Dir: Steve Royal Cat Lady Chronicles Guest Star Dir: Angela Dugan In The Mix Co-host PBS THEATRE (partial list) Rock Bottom Rising Ensemble Second City Hollywood MainStage She Said What? Lead T.S.T. Co./NAACP Play Fest., 2013 Twisted Dance Lead Towne St. Theatre Co., LA I'll Take a Side of Stories Lead Soho Repertory Theatre, NY Remote Control Lead Tribeca Performing Arts Theatre, NY B.Y.O.B. Lead McKenzie Theatre, LA Love, Lust, or Infatuation Lead Hollywood Fight Club Theatre, LA My Children My Africa Lead Wheaton College, MA Afros &Ass Whoopins Understudy Second City Hollywood, MainStage, LA COMMERCIAL/PRINT Available upon request TRAINING Comedy Intensive/On Going Technique Lesly Kahn LA On Camera/Scene Study Paul Currie LA Cold Reading/Acting Technique Brian Reise LA Cold Reading/Audition Technique Amy Lyndon LA Acting for the Camera Karen Ludwig NY Scene Study Jacqueline Cohen NY Improv/Sketch (Conservatory Graduate) The Second City LA Improv Colton Dunn/Will McLaughlin LA SPECIAL SKILLS Dance: Intermediate-Caribbean, Hip-Hop, House, Latin, Swing; Beginner- Waltz, Tango Athletic: Falling Off Surf Boards, College level- Basketball, H.S. -

Street New York City the Singer Building Mott 174 Street New York City

THE SINGER BUILDING MOTT 174 STREET NEW YORK CITY THE SINGER BUILDING MOTT 174 STREET NEW YORK CITY A beautiful and historic corner building with new infrastructure and rooftop, in one of Lower Manhattan’s hottest neighborhoods A full building opportunity, perfect for any combination of retail, office, HQ, F&B, or private club use. 174 MOTT STREET FASHION/LIFESTYLE ATTRACTIONS NEW DEVELOPMENTS MUSEUMS RESTAURANTS /FOOD 1 Supreme 40 Museum of Ice Cream 48 75 Kenmare 51 New Museum 55 Odeon 2 KITH 41 Metrograph 49 152 Elizabeth 52 Tenement Museum 56 Freemans 3 Hypebeast 42 First Street Green 50 40 Bleecker 53 ICPM 57 Katz Delicatessen 4 Essex Crossing Cultural Park 54 Museum of Chinese in America 58 Dirty French 5 Nike 43 Sara D. Roosevelt Park 59 Taverna di Bacco 6 REI 44 Olsen Gruin Gallery 60 Sweet Chick 7 Adidas 45 Williamsburg Bridge 61 Serafina 8 Glossier 46 Capitale 62 The Fat Radish 9 Apple 47 Canal Street Market 29 63 Nom Wah Tea Parlor 10 Russ & Daughters Shop 64 Milk Bar 11 Equinox 65 Il Laboratorio del Gelato 12 Soul Cycle East 66 Ludlow Coffee Supply 13 Y7 Studio 67 El Rey 28 Village 14 Opening Ceremony 82 NoHo 68 Clinton Street Baking Co. 15 Bloomingdales 69 Spreadhouse Café 2 16 Reformation BOWERY 42 70 Russ & Daughters Café 6 50 HOUSTON ST 17 Muji 76 68 71 Irving Farm BROADWAY 57 65 10 11 18 Zara LAFAYETTE ST 58 72 Doughnut Plant 73 19 Allbirds B D 6 26 34 35 59 66 73 Whole Foods 20 Maison Margiela F M 60 74 Essex Street Market 67 21 Issey Miyake 64 Lower East 75 Butcher’s Daughter 5 22 Aimé Leon Dore 51 Side 76 Cha Cha Matcha -

Brand-New Theaters Planned for Off-B'way

20100503-NEWS--0001-NAT-CCI-CN_-- 4/30/2010 7:40 PM Page 1 INSIDE THE BEST SMALL TOP STORIES BUSINESS A little less luxury NEWS YOU goes a long way NEVER HEARD on Madison Ave. ® Greg David Page 11 PAGE 2 Properties deemed ‘distressed’ up 19% VOL. XXVI, NO. 18 WWW.CRAINSNEWYORK.COM MAY 3-9, 2010 PRICE: $3.00 PAGE 2 ABC Brand-new News gets cut theaters to the bone planned for PAGE 3 Bankrupt St. V’s off-B’way yields rich pickings PAGE 3 Hit shows and lower prices spur revival as Surprise beneficiary one owner expands of D.C. bank attacks IN THE MARKETS, PAGE 4 BY MIRIAM KREININ SOUCCAR Soup Nazi making in the past few months, Catherine 8th Ave. comeback Russell has been receiving calls constant- ly from producers trying to rent a stage at NEW YORK, NEW YORK, P. 6 her off-Broadway theater complex. In fact, the demand is so great that Ms. Russell—whose two stages are filled with the long-running shows The BUSINESS LIVES Fantasticks and Perfect Crime—plans to build more theaters. The general man- ager of the Snapple Theater Center at West 50th Street and Broadway is in negotiations with landlords at two midtown locations to build one com- plex with two 249-seat theaters and an- other with two 249-seat theaters and a 99-seat stage. She hopes to sign the leases within the next two months and finish the theaters by October. “There are not enough theaters cen- GOTHAM GIGS by gettycontour images / SPRING AWAKENING: See NEW THEATERS on Page 22 Healing hands at the “Going to Broadway has Bronx Zoo P. -

Qurrat Ann Kadwani: Still Calling Her Q!

1 More Next Blog» Create Blog Sign In InfiniteBody art and creative consciousness by Eva Yaa Asantewaa Tuesday, May 6, 2014 Your Host Qurrat Ann Kadwani: Still calling her Q! Eva Yaa Asantewaa Follow View my complete profile My Pages Home About Eva Yaa Asantewaa Getting to know Eva (interview) Qurrat Ann Kadwani Eva's Tarot site (photo Bolti Studios) Interview on Tarot Talk Contact Eva Name Email * Message * Send Contribute to InfiniteBody Subscribe to IB's feed Click to subscribe to InfiniteBody RSS Get InfiniteBody by Email Talented and personable Qurrat Ann Kadwani (whose solo show, They Call Me Q!, I wrote about Email address... Submit here) is back and, I hope, every bit as "wicked smart and genuinely funny" as I observed back in September. Now she's bringing the show to the Off Broadway St. Luke's Theatre , May 19-June 4, Mondays at 7pm and Wednesdays at 8pm. THEY CALL ME Q is the story of an Indian girl growing up in the Boogie Down Bronx who gracefully seeks balance between the cultural pressures brought forth by her traditional InfiniteBody Archive parents and wanting acceptance into her new culture. Along the journey, Qurrat Ann Kadwani transforms into 13 characters that have shaped her life including her parents, ► 2015 (222) Caucasian teachers, Puerto Rican classmates, and African-American friends. Laden with ▼ 2014 (648) heart and abundant humor, THEY CALL ME Q speaks to the universal search for identity ► December (55) experienced by immigrants of all nationalities. ► November (55) Program, schedule and ticket information ► October (56) ► September (42) St. -

2021-02-12 FY2021 Grant List by Region.Xlsx

New York State Council on the Arts ‐ FY2021 New Grant Awards Region Grantee Base County Program Category Project Title Grant Amount Western New African Cultural Center of Special Arts Erie General Support General $49,500 York Buffalo, Inc. Services Western New Experimental Project Residency: Alfred University Allegany Visual Arts Workspace $15,000 York Visual Arts Western New Alleyway Theatre, Inc. Erie Theatre General Support General Operating Support $8,000 York Western New Special Arts Instruction and Art Studio of WNY, Inc. Erie Jump Start $13,000 York Services Training Western New Arts Services Initiative of State & Local Erie General Support ASI General Operating Support $49,500 York Western NY, Inc. Partnership Western New Arts Services Initiative of State & Local Erie Regrants ASI SLP Decentralization $175,000 York Western NY, Inc. Partnership Western New Buffalo and Erie County Erie Museum General Support General Operating Support $20,000 York Historical Society Western New Buffalo Arts and Technology Community‐Based BCAT Youth Arts Summer Program Erie Arts Education $10,000 York Center Inc. Learning 2021 Western New BUFFALO INNER CITY BALLET Special Arts Erie General Support SAS $20,000 York CO Services Western New BUFFALO INTERNATIONAL Electronic Media & Film Festivals and Erie Buffalo International Film Festival $12,000 York FILM FESTIVAL, INC. Film Screenings Western New Buffalo Opera Unlimited Inc Erie Music Project Support 2021 Season $15,000 York Western New Buffalo Society of Natural Erie Museum General Support General Operating Support $20,000 York Sciences Western New Burchfield Penney Art Center Erie Museum General Support General Operating Support $35,000 York Western New Camerta di Sant'Antonio Chamber Camerata Buffalo, Inc. -

ŁNY@Night 1St Edition.Qxd

NY@Night 1st Edition.qxd 8/21/2006 1:15 PM Page 109 NY@Night 1st Edition.qxd 8/21/2006 1:15 PM Page 110 Originally a commercial district not designated for residential housing, the 17 name SoHo was coined by developers to 8 refer to the neighborhood South of 34 Houston Street. 14 24 16 1 21 However, SoHo is not just a geographical location, 2 it is a statement, in which residents and visitors alike proudly stake a claim to being a part of this 19 37 20 13 36 international hotbed of fashion and art. Known for 3 the small art galleries, sidewalk trendy cafes, and 32 33 boutiques that line its streets, SoHo is an 6 experience to be slowly sipped, absorbed block by block and savored over an intimate dinner. 18 10 30 38 29 31 7 Having outgrown its early radical persona, SoHo 5 25 23 27 has carved out a popular niche for itself — 9 26 4 35 culturally and economically. The same lofts once prized for their location, are no longer inexpensive. The escalated cost of living is now forcing up-and- coming artists to flee to Neo-Bohemian enclaves like Williamsburg in Brooklyn, eroding SoHo’s cutting-edge reputation. The area’s established 22 15 chic character, however, is firmly embedded. 28 Bordering SoHo and the Lower East Side, Little Italy remains the heart of New York’s Old World 11 Italian culture — a character slowly being whittled 12 away by time. This is where it all started. The turn- of-the-century flood of Italian immigrants into the area’s cramped tenements that were the launching pad from which they have achieved great heights. -

THE MYSTERY of LOVE & SEX Cast Announcement

LINCOLN CENTER THEATER CASTING ANNOUNCEMENT FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE, PLEASE MAMOUDOU ATHIE, DIANE LANE, GAYLE RANKIN, TONY SHALHOUB TO BE FEATURED IN LINCOLN CENTER THEATER’S PRODUCTION OF “THE MYSTERY OF LOVE & SEX” A new play by BATHSHEBA DORAN Directed by SAM GOLD PREVIEWS BEGIN THURSDAY, FEBRUARY 5, 2015 OPENING NIGHT IS MONDAY, MARCH 2, 2015 AT THE MITZI E. NEWHOUSE THEATER Lincoln Center Theater (under the direction of André Bishop, Producing Artistic Director) has announced that Mamoudou Athie, Diane Lane, Gayle Rankin, and Tony Shalhoub will be featured in its upcoming production of THE MYSTERY OF LOVE & SEX, a new play by Bathsheba Doran. The production, which will be directed by Sam Gold, will begin previews Thursday, February 5 and open on Monday, March 2 at the Mitzi E. Newhouse Theater (150 West 65 Street). Deep in the American South, Charlotte and Jonny have been best friends since they were nine. She's Jewish, he's Christian, he's black, she's white. Their differences intensify their connection until sexual desire complicates everything in surprising, compulsive ways. An unexpected love story about where souls meet and the consequences of growing up. THE MYSTERY OF LOVE & SEX will have sets by Andrew Lieberman, costumes by Kaye Voyce, lighting by Jane Cox, and original music and sound by Daniel Kluger. BATHSHEBA DORAN’s plays include Kin, also directed by Sam Gold (Playwrights Horizons), Parent’s Evening (Flea Theater), Ben and the Magic Paintbrush (South Coast Repertory Theatre), Living Room in Africa (Edge Theater), Nest, Until Morning, and adaptations of Dickens’ Great Expectations, Maeterlinck’s The Blind, and Peer Gynt. -

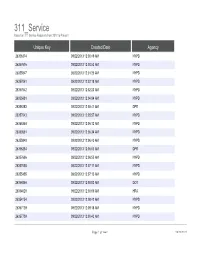

311 Service Based on 311 Service Requests from 2010 to Present

311_Service Based on 311 Service Requests from 2010 to Present Unique Key Created Date Agency 26356374 09/22/2013 12:00:49 AM NYPD 26357616 09/22/2013 12:00:53 AM NYPD 26355847 09/22/2013 12:01:29 AM NYPD 26357061 09/22/2013 12:02:18 AM NYPD 26357542 09/22/2013 12:02:20 AM NYPD 26355691 09/22/2013 12:04:04 AM NYPD 26356283 09/22/2013 12:05:41 AM DPR 26357043 09/22/2013 12:05:57 AM NYPD 26356354 09/22/2013 12:06:12 AM NYPD 26353561 09/22/2013 12:06:34 AM NYPD 26355849 09/22/2013 12:06:43 AM NYPD 26356284 09/22/2013 12:06:53 AM DPR 26357696 09/22/2013 12:06:55 AM NYPD 26357058 09/22/2013 12:07:11 AM NYPD 26355455 09/22/2013 12:07:13 AM NYPD 26356856 09/22/2013 12:08:00 AM DOT 26354028 09/22/2013 12:08:09 AM HRA 26354154 09/22/2013 12:08:42 AM NYPD 26357139 09/22/2013 12:09:18 AM NYPD 26357709 09/22/2013 12:09:42 AM NYPD Page 1 of 1440 09/28/2021 311_Service Based on 311 Service Requests from 2010 to Present Complaint Type Descriptor Noise - Vehicle Car/Truck Horn Noise - Residential Loud Music/Party Noise - Commercial Loud Music/Party Noise - Residential Loud Music/Party Noise - Street/Sidewalk Loud Music/Party Illegal Parking Blocked Sidewalk Damaged Tree Tree Leaning/Uprooted Noise - Residential Loud Music/Party Noise - Residential Loud Music/Party Noise - Residential Loud Music/Party Noise - Residential Loud Music/Party Damaged Tree Tree Leaning/Uprooted Noise - Commercial Loud Music/Party Noise - Residential Loud Talking Illegal Parking Posted Parking Sign Violation Street Light Condition Lamppost Damaged Benefit Card Replacement Medicaid -

216 41 Cooper Square 89 Abyssinian Baptist Church 165 Alimentation 63

216 index 41 Cooper Square 89 Angel’s Share 92 The Half King Bar & Attaboy 56 Restaurant 83 A Bar 54 127 The Vig Bar 63 Bar Veloce 93 Verlaine 57 Abyssinian Baptist Bembe 173 White Horse Tavern 74 Church 165 Bemelmans Bar 147 Baseball 206 Alimentation 63, 75, 84, Blind Tiger Ale House 73 Basketball 206 93, 102, 157 d.b.a. East Village 93 Bateau 197 American Museum of Dos Caminos 102 Battery Maritime Natural History 153 Gallow Green 83 Building 46 Apollo Theater 164 Great Hall Balcony Bar 147 Battery Park 46 Appartements 184 Henrietta Hudson 74 Hudson Common 128 Battery Park City 41 Appellate Division Hudson Malone 118 Beacon Theatre 156 Courthouse of the New Jake’s Dilemma 156 York State Supreme Bedford Avenue 171 La Birreria 102 Belvedere Castle 136 Court 95 Le Bain 83 Bethesda Fountain & Argent 199 Library Bar 128 Terrace 135 Astoria 175 McSorley’s Old Ale Astor Place 88 House 93 Bijouteries 119 Auberges de Paddy Reilly’s Music Birdland 128 jeunesse 185 Bar 102 Blue Note 74 Paris Café 40 Boerum Hill 171 Autocar 183 Pegu Club 63 Bow Bridge 136 Avery Architectural & Please Don’t Tell 93 Fine Arts Library 162 Roof Garden Café and Bowery Ballroom 57 Avion 180 Martini Bar 147 British Empire Sake Bar Decibel 93 Building 109 B Schiller’s Liquor Bar 57 Broadway 120 Shalel Lounge 156 Bronx 176 Banques 199 Sky Terrace 128 Bronx Zoo 177 Bars et boîtes S.O.B.’s 63 Brookfield Place 42 de nuit 200 The Brooklyn Barge 173 68 Jay Street Bar 173 The Dead Rabbit Grocery Brooklyn 168 Abbey Pub 156 and Grog 40 Brooklyn Botanic Aldo Sohm Wine Bar 127 The -

NYC ARTS AUDIENCES Attendance at NYC Cultural Venues

NYC ARTS AUDIENCES Attendance at NYC Cultural Venues 2005 ALLIANCE for THE ARTS We are grateful for the cooperation of the directors and staff of the cultural organizations throughout New York City who supplied information for this survey. In many cases, they also agreed to be interviewed to help the research team understand the complexity of measuring attendance in a standardized way in New York City. This study was made possible by the generous support of the American Express Foundation, Mary Beth Salerno, Vice President. The Alliance’s research activities are supported in part by the City of New York, Michael R. Bloomberg, Mayor, and Gifford Miller, Speaker, New York City Council, through the Department of Cultural Affairs, Kate D. Levin, Commissioner. Alliance for the Arts Randall Bourscheidt, President Anne Coates, Vice President Catherine Lanier, Director of Research Johanna Arendt, Research Associate Fern Glazer, Editor Stephanie Margolin, Publications Manager Sara Loughlin, Designer 330 West 42nd Street, Suite 1701 New York, NY 10036 (212) 947-6340 Fax: (212) 947-6416 www.allianceforarts.org Board of Trustees Paul Beirne, Chairman. Randall Bourscheidt, President. Anita Contini, Karen Gifford, Fiona Howe Rudin, J. P. Versace, Jr., Vice Chairmen; William Smith, Treasurer. Laurie Beckelman, Raoul Bhavnani Linda Boff, John Breglio, Kevin R. Brine, Theodore Chapin, Robert Clauser, Charles Cowles, James H. Duffy, Heather Espinosa, Paul Gunther, Ashton Hawkins, Patricia C. Jones, Eric Lee, Robert Marx Richard Mishaan, Richard Mittenthal, Alexandra Munroe, Joseph J. Nicholson, Marc Porter, Betty A. Prashker, Susan Ralston, Justin Rockefeller, Jerry Scally, Frances Schultz, Andrew Solomon Paul Washington, Tim Zagat Copyright © 2005 Alliance for the Arts 1 fkqolar`qflk= This report is based on the first study of the Understanding audience composition is a challenge audience for nonprofit cultural activity in New to an industry which is not only fragmented, large York City. -

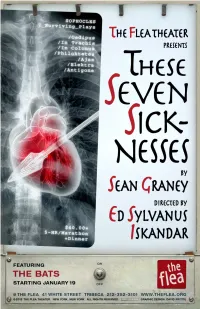

These-Seven-Sicknesses.Pdf

THE FLEA THEATER JIM SIMP S ON ARTISTIC DIRECTOR CAROL OS TROW PRODUCING DIRECTOR BETH DEM B ROW MANAGING DIRECTOR PRESENTS THE NEW YORK PREMIERE OF THESE SEVEN SICKNESSES WRITTEN BY SEAN GRANEY DIRECTED BY ED SYLVANU S IS KAN D AR FEATURING THE BAT S JULIA NOULIN -MERAT SET DESIGN CARL WIEMANN LIGHTING DESIGN LOREN SHAW COSTUME DESIGN PATRI C K METZ G ER SOUND DESIGN MI C HAEL WIE S ER FIGHT DIRECTION DAVI D DA bb ON MUSIC DIRECTION GRE G VANHORN DRAMATURG ED WAR D HERMAN , KARA KAUFMAN STAGE MANAGMENT These Seven Sicknesses was originally incubated in New York City during Lab 2 at Exit, Pursued by a Bear (EPBB), March 2011; Ed Sylvanus Iskandar, Artistic Director. THESE SEVEN SICKNESSES CAST (IN ORDER OF APPEARANCE ) PROLOGUE Orderly..............................................................................................................Will Turner Nurse 1.........................................................................................................Glenna Grant New Nurse .........................................................................................Tiffany Abercrombie Nurse 2........................................................................................................Eloise Eonnet Nurse 3.............................................................................................Marie Claire Roussel Nurse 4...........................................................................................................Jenelle Chu Nurse 5.........................................................................................................Olivia -

Promoting Charitable Giving for Forty Years. 575 Madison Avenue, Suite 703 • New York, NY 10022

WWW.JCFNY.ORG 2012 ANNUAL REPORT L E B E R A C T F E C S J Y E E C A I R V S R O F S E Jewish Communal Fund Promoting charitable giving for forty years. 575 Madison Avenue, Suite 703 • New York, NY 10022 Phone: 866.580.4523 • 212.752.8277 – HERBERT M. SINGER, FOUNDING PRESIDENT OF JCF, SEPTEMBER 1974 SEPTEMBER JCF, OF PRESIDENT FOUNDING SINGER, M. HERBERT – “We have forged a tool of great social potential…” social great of tool a forged have “We Jewish Communal Fund’s Residents of the following states may obtain financial and/or licensing information from their generous donors had a profound states, as indicated. Registration with these states, or any other state, does not imply endorsement impact on charities in every sector, by the state. granting more than $282 million Connecticut: Information filed with the Attorney in fiscal year 2012. General concerning this charitable solicitation may be obtained from the Department of Consumer Protection, Public Charities Unit, 165 Capitol Avenue, Hartford, CT 06106 or by calling Community Organizations $17.1 M Community Organizations860-713-6170. $39 M $22.6 M Culture-GeneralCulture-General Florida: SC No. CH17581. A copy of the official Culture-Jewish Culture-Jewish registration and financial information may $32 M $28.9 M Education-GeneralEducation-General be obtained from the Division of Consumer Services by calling toll free, from within the Education-JewishEducation-Jewish $6.6 M state, 800-435-7352. Registration does not E $14.4 M Community OrganizationsEnvironment E L B R $17.1 M Community OrganizationsEnvironment imply endorsement, approval or recommendation C A Health T Health by the state.