MANAGING the INHERITANCE: GAINS, LOSSES, and CHALLENGES in the TWELFTH, THIRTEENTH, and FOURTEENTH CENTURIES the Previous Chapte

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

LOCAL GOVERNMENT COMMISSION for ENGLAND PERIODIC ELECTORAL REVIEW of EPPING FOREST Final Recommendations for Ward Boundaries In

S R A M LOCAL GOVERNMENT COMMISSION FOR ENGLAND Deerpark Wood T EE TR S EY DS LIN Orange Field 1 Plantation 18 BURY ROAD B CLAVERHAM Galleyhill Wood Claverhambury D A D O D LR A O IE R F Y PERIODIC ELECTORAL REVIEW OF EPPING FOREST R LY U B O M H A H Bury Farm R E V A L C Final Recommendations for Ward Boundaries in Loughton and Waltham Abbey November 2000 GR UB B' S H NE Aimes Green ILL K LA PUC EPPING LINDSEY AND THORNWOOD Cobbinsend Farm Spratt's Hedgerow Wood COMMON WARD B UR D Y R L A D N Monkhams Hall N E E S N I B B Holyfield O C Pond Field Plantation E I EPPING UPLAND CP EPPING CP WALTHAM ABBEY NORTH EAST WARD Nursery BROADLEY COMMON, EPPING UPLAND WALTHAM ABBEY E AND NAZEING WARD N L NORTH EAST PARISH WARD A O School L N L G L A S T H R N E R E E F T ST JOHN'S PARISH WARD Government Research Establishment C Sports R The Wood B Ground O U O House R K G Y E A L D L A L M N E I E L Y E H I L L Home Farm Paris Hall R O Warlies Park A H D o r s e m Griffin's Wood Copped Hall OAD i l R l GH HI EPPING Arboretum ƒƒƒ Paternoster HEMNALL House PARISH WARD WALTHAM ABBEY EPPING HEMNALL PIC K H PATERNOSTER WARD ILL M 25 WARD z z z z z z z z z z z z z z z z z z z z z z z z z z z z z z z z z z z z z z z z z z z z z z z z z EW WALTHAM ABBEY EYVI ABB AD PATERNOSTER PARISH WARD RO IRE SH UP R School School Raveners Farm iv e r L Copthall Green e e C L N L R a A v O H ig The Warren a O ti K D o K C A n I E T O WALTHAM ABBEY D R M MS Schools O I L O E R B Great Gregories OAD ILL R Farm M H FAR Crown Hill AD O Farm R Epping Thicks H IG H AD N RO -

Service Numbers Operator Service From/To Service

Service Numbers Operator Service From/To Service Periods 2 Arriva Harlow - Great Parndon Monday to Saturday evenings 4 Regal Litte Parnden - Harlow Sunday 4 Arriva Latton Bush - Harlow Monday to Saturday evenings 5 Arriva Sumners - Kingsmoor - Harlow - Pinnacles Monday to Saturday 7 Stephensons of Essex Only Southend - Rayleigh Monday to Saturday Evening Services 9 Regal Braintree - Great Bardfield Saturday 9 Stephensons of Essex Great Holland - Walton-on-the-Naze Monday to Friday 10 Regal Harlow Town Station - Church Langley Sunday 10 Arriva Harlow - Church Langley Monday to Saturday evenings 11 Regal Harlow - Sumners - Passmore - Little Parnden Sunday 12 Regal Old Harlow - Harlow - Kingsmoor Sunday 14 Stephensons of Essex Southend - Shoebury/Foulness Monday to Saturday 32 Stephensons of Essex Chelmsford - Ongar Monday to Saturday 45 Regal Chelmsford - Oxney Green Monday to Friday Evening Services 46 Nibs Buses Chelmsford - Ongar (Services 46A-46-F not affected) Monday to Friday 47 Regal Harlow - Ongar Tuesday, Thursday, Friday, Saturday 52 Regal Galleywood - Pleshey Monday to Friday 66 First Essex Colchester - Rowhedge Monday to Saturday evenings 66 First Essex Colchester - W Bergholt Sunday & Public Holiday 70 Regal Only Colchester - Braintree Monday to Saturday evenings 75 Regal Only Colchester - Maldon Monday to Saturday Evening Services 75 First Essex Maldon - Colchester Sunday & Public Holiday 88 Regal Only Colchester - Halstead Sunday & Public Holidays 89 Regal Only Great Yeldham - Braintree Monday to Friday Single Peak Journey -

Abridge Buckhurst Hill Chigwell Coopersale Epping Fyfield

Abridge Shell Garage, London Road Buckhurst Hill Buckhurst Hill Library, 165 Queen’s Road (Coronaviris pandemic – this outlet is temporarily closed) Buckhurst Hill Convenience Store, 167 Queen’s Road (Coronaviris pandemic – this outlet is temporarily closed) Premier & Post Office, 38 Station Way (Coronaviris pandemic – this outlet is temporarily closed) Queen’s Food & Wine, 8 Lower Queen’s Road Valley Mini Market, 158 Loughton Way Valley News, 50 Station Way Waitrose, Queens Road Chigwell Lambourne News, Chigwell Row Limes Centre, The Cobdens (Coronaviris pandemic – this outlet is temporarily closed) Chigwell Parish Council, Hainault Road (Coronaviris pandemic – this outlet is temporarily closed) L. G. Mead & Son, 19 Brook Parade (Coronaviris pandemic – this outlet is temporarily closed) Budgens Supermarket, Limes Avenue Coopersale Hambrook, 29 Parklands Handy Stores, 30 Parklands Epping Allnut Stores, 33a Allnuts Road Epping Newsagent, 83 High Street (Coronaviris pandemic – this outlet is temporarily closed) Epping Forest District Council Civic Offices, 323 High Street (Coronaviris pandemic – this outlet is temporarily closed) Epping Library, St. Johns Road (Coronaviris pandemic – this outlet is temporarily closed) House 2 Home, 295 High Street M&S Simply Food, 237-243 High Street Tesco, 77-79 High Street Fyfield Fyfield Post Office, Ongar Road High Ongar Village Store, The Street Loughton Aldi, Epping Forest Shopping Park Baylis News, 159 High Road Epping Forest District Council Loughton Office, 63 The Broadway -

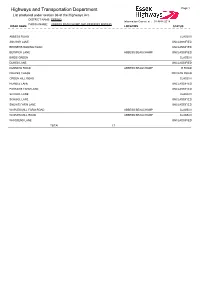

Highways and Transportation Department Page 1 List Produced Under Section 36 of the Highways Act

Highways and Transportation Department Page 1 List produced under section 36 of the Highways Act. DISTRICT NAME: EPPING Information Correct at : 01-APR-2018 PARISH NAME: ABBESS BEAUCHAMP AND BERNERS RODING ROAD NAME LOCATION STATUS ABBESS ROAD CLASS III ANCHOR LANE UNCLASSIFIED BERNERS RODING ROAD UNCLASSIFIED BERWICK LANE ABBESS BEAUCHAMP UNCLASSIFIED BIRDS GREEN CLASS III DUKES LANE UNCLASSIFIED DUNMOW ROAD ABBESS BEAUCHAMP B ROAD FRAYES CHASE PRIVATE ROAD GREEN HILL ROAD CLASS III HURDLE LANE UNCLASSIFIED PARKERS FARM LANE UNCLASSIFIED SCHOOL LANE CLASS III SCHOOL LANE UNCLASSIFIED SNOWS FARM LANE UNCLASSIFIED WAPLES MILL FARM ROAD ABBESS BEAUCHAMP CLASS III WAPLES MILL ROAD ABBESS BEAUCHAMP CLASS III WOODEND LANE UNCLASSIFIED TOTAL 17 Highways and Transportation Department Page 2 List produced under section 36 of the Highways Act. DISTRICT NAME: EPPING Information Correct at : 01-APR-2018 PARISH NAME: BOBBINGWORTH ROAD NAME LOCATION STATUS ASHLYNS LANE UNCLASSIFIED BLAKE HALL ROAD CLASS III BOBBINGWORTH MILL BOBBINGWORTH UNCLASSIFIED BRIDGE ROAD CLASS III EPPING ROAD A ROAD GAINSTHORPE ROAD UNCLASSIFIED HOBBANS FARM ROAD BOBBINGWORTH UNCLASSIFIED LOWER BOBBINGWORTH GREEN UNCLASSIFIED MORETON BRIDGE CLASS III MORETON ROAD CLASS III MORETON ROAD UNCLASSIFIED NEWHOUSE LANE UNCLASSIFIED PEDLARS END UNCLASSIFIED PENSON'S LANE UNCLASSIFIED STONY LANE UNCLASSIFIED TOTAL 15 Highways and Transportation Department Page 3 List produced under section 36 of the Highways Act. DISTRICT NAME: EPPING Information Correct at : 01-APR-2018 PARISH NAME: -

Waltham Abbey / Cheshunt Walk (BW)

Ware to Waltham Abbey Farm and Wetland Trail Route Summary: A circular route linking the Lee Valley Park Farms to the wetlands of River Lee Country Park. An ideal route for all ages and abilities throughout the year. The route travels west across the three waterways before turning south around North Metropolitan Pit and returning along the east side of Seventy Acres Lake. Distance: 3 miles Terrain: Surfaced pathways, several bridges (two with steep inclines) and several walk- around gates. Starting Point: Lee Valley Park Farms car park Stubbins Hall Lane, Crooked Mile, Waltham Abbey, EN9 2EG Proceed across the extended car park and join the surfaced pathway on the left. At the field gate turn right and continue, turn right at the signpost and follow the pathway to the Fishers Green overflow car park. Proceed through the car park and turn left onto a stony grass path alongside the Flood Relief Channel, heading south. Proceed through a walk-around gate, turning right over a bridge across the Flood Relief Channel to the two field gates. Proceed through the walk-around gate on the left and continue along the surfaced path passing the National Grid sub station on the right. Turn left, over the metal bridge, crossing the Old River Lee, heading south. Turn right over the wooden bridge, crossing River Lee Navigation and proceed along the causeway dividing North Metropolitan Pit. Bear to the left, heading south past Nightingale Wood and Pochard Viewpoint. Turn right over the red brick bridge crossing Small River Lee, turning left and heading south. -

Spring 2021 North Weald, Passingford, Lambourne and Theydon Bois

1 Spring 2021 North Weald, Passingford, Lambourne and Theydon Bois Introduction to your local officer PC Andy Cook is the Community Policing Team beat officer for North Weald, Passingford (to include Stanford Rivers, Stapleford Abbotts and Tawney, and Theydon Garnon and Mount), Lambourne (to include Abridge and Lambourne End) and Theydon Bois. He has been an officer for 17 years, and performed a number of roles within the Epping Forest District as well as Harlow. PC Cook joined the Epping Forest District Community Policing Team in 2008. Day to day work for PC Cook involves patrolling his beat areas, addressing local concerns and carrying out enquiries for various crimes allocated to him which have occurred in these areas. These include low and medium risk hate crimes. PC Cook works particularly closely with the various Parish Councils, attending meetings and providing updates where possible. He has put his contact details in local publications and Above: PC Andy Cook welcomes being contacted, and would also be happy to visit for crime prevention advice. Introduction from the District Commander, Ant Alcock “Hi everybody. My name is Ant Alcock and I’m a Chief Inspector with Essex Police, currently the District Commander for Epping Forest and Brentwood where I hold responsibility for policing. I wanted to take the time in this edition to explain the policing structure within Epping Forest. Based at Loughton Police Station, there is the Local Policing Team (LPT), Community Policing Team (CPT), Town Centre Teams (TCT) and the Criminal Investigations Department (CID). LPT provide the 24/7 cover responding to emergency and non-emergency incidents. -

19LAD0095 Countryside Properties

Epping Forest Local Plan Examination Hearing Statement Matter 4 – The Spatial Strategy/Distribution of Development Prepared by Strutt & Parker on behalf of Countryside Properties (19LAD0095) January 2019 Countryside Properties (Stakeholder ID 19LAD0095) Matter 4 Hearing Statement Context 1. Strutt & Parker have participated in the plan-making process on behalf of Countryside Properties (Local Plan Examination Stakeholder ID 19LAD0095 throughout the preparation of the Epping Forest Local Plan, and in relation to land at North Weald Bassett. This has included representations on the Local Plan Submission Version (LPSV) (Regulation 19) consultation (Representation ID 19LAD0095-1 and 19LAD0095-27). 2. Countryside Properties have the principal land interests in relation to the North Weald Bassett residential site-specific allocations at NWB.R1 to R.5. They have control of NWB.R3, land south of Vicarage Lane, which is proposed for allocation for approximately 728 homes, the largest of the 5 allocations at North Weald Bassett. 3. As per our LPSV representations, Countryside Properties’ overall position is one of firm support for the LPSV, albeit with some overarching concerns regarding matters of detail and soundness. 4. As such, we consider, that subject to some relatively modest modifications to the LPSV, the Local Plan can be made sound. 5. This Hearing Statement is made in respect of the Epping Forest Local Plan Examination Matter 4 – The Spatial Strategy/Distribution of Development, and addresses Issues 2, 3, 4 and 5. 6. We have sought to avoid repeating matters within this Hearing Statement which were raised within our representations on the LPSV. 7. The LPSV was submitted for examination before 24 January 2019 – the deadline in the 2018 National Planning Policy Framework (NPPF) transitional arrangements for Local Plans to be examined under the 2012 NPPF. -

Appendix B1.1 – Overview of Assessment

EB801B Epping Forest District Council Epping Forest District Local Plan Report on Site Selection B1.1 Overview of Assessment of Residential Sites | Issue | September 2016 EB801B Appendix B1.1 Site proceeds at this stage. Site references in italic denote that this site was orignially one part of a site Overview of Assessment of Residential Sites Site does not proceed at this stage. SR-0111 comprising multiple parts sharing a single SLAA reference number. An This stage is not applicable for this site. amendment to the site reference was made to create a unique identifier for each site. Settlement (Sites Pre- Site Ref Address Parish proceeding to Promoted Use Secondary Use Split Site Stage 1 Stage 2 Stage 3 Stage 4 Justification Stage 1 Stage 2 only) 16 SITE_01 Land south of Roding Lane, Roding River Chigwell Housing Site subject to Major Policy Constraint. Meadows, Buckhurst Hill 16 SITE_02 Land north of Vicarage Lane, Chigwell, IG7 6LS, Chigwell Chigwell Housing The site should not proceed for further testing. UK SR-0001 Prospect Nursery, Old Nazeing Road, Nazeing, Nazeing Housing Site subject to Major Policy Constraint. Broxbourne SR-0002 Wealdstead, Toot Hill Road, Greensted, Ongar, Standford Rivers Housing Site subject to Major Policy Constraint. Essex, CM5 9LJ SR-0003 Two fields East and West of Church Lane (North North Weald North Weald Housing Site is recommended for allocation. of Lancaster Road), North Weald Bassett, Essex Bassett Bassett SR-0004 Land opposite The White House, Middle Street, Nazeing Housing Site subject to Major Policy Constraint. Nazeing, Essex, EN9 2LW SR-0005 54 Centre Drive, Epping Epping Housing Site is subject to extant planning permission dated prior to 31st July 2016. -

01-Ffr-Appendix1-Slaa Site Sieving-20160928

EB803A Epping Forest District: Settlement Capacity Study APPENDIX 1: SLAA SITE SIEVING INITIAL REASON SLAA SITE SITE SIZE SETTLEMENT DESCRIPTION SITE FOR ID (HA) POOL REMOVAL SR-0005 0.19 Epping 54 Centre Drive, Epping Y Waltham Mason Way, Ninefields, SR-0021 0.24 Abbey Waltham Abbey, Essex Y Rear of 101-103 High Street, SR-0022 0.1 Ongar Chipping Ongar Y Land at 20 Albion Hill, SR-0059 0.29 Loughton Loughton Y SR-0132C 0.5 Epping Tower Road Allotments Y Fire Station, Sewardstone Waltham SR-0219 0.64 Road, Waltham Abbey, Essex, Abbey EN9 1P Y 1-2 Marconi Bungalows, High North Weald SR-0220 0.17 Road, North Weald, Epping, Bassett CM16 Y Queens Road, Lower Car Park, SR-0225 0.43 Buckhurst Hill Buckhurst Hill, IG9 5 Y Loughton LU Car park, SR-0226 1 Loughton adjacent to station, off old station r Y Debden LU Car Park and land SR-0227 1.66 Loughton adjacent to station, off Chigwel Y SR-0228A 0.36 Theydon Bois Theydon Bois LU Car Park Y Epping LU Car Park and land SR-0229 1.6 Epping adjacent to station, off station Y Former electricity sub-station, SR-0230 0.17 Buckhurst Hill off station way, Roding Vall Y North Weald Hurricane Way Industrial SR-0274 6.4 Bassett Estate, North Weald Bassett Y North Weald High Road, North Weald, Access SR-0275 1 Bassett Industrial Estate, CM16 6EG N Issues Bower Hill Industrial Estate, SR-0278 0.38 Epping Employment Y Oakwood Hill Industrial Estate SR-0279 3.87 Loughton (East) Y Oakwood Hill Industrial Estate Access SR-0280 0.55 Loughton (West) N Issues St Johns Road Area, Epping SR-0281 3.05 Epping Town Centre -

Body of Document

AREA PLANS SUB-COMMITTEE ‘WEST’ 20 January 2016 INDEX OF PLANNING APPLICATIONS OFFICER ITEM REFERENCE SITE LOCATION PAGE RECOMMENDATION EPF/1593/15 6 Carters Lane Epping Green Grant Permission 1. Epping 26 (With Conditions) Essex CM16 6QJ EPF/2133/15 3 Green Close Epping Green Grant Permission 2. Epping 32 (With Conditions) Essex CM16 6PS EPF/2445/15 Red Roofs Low Hill Road Grant Permission 3. Roydon (Subject to Legal 36 Harlow Essex Agreement) CM19 5JN EPF/2523/15 Emerald Riverside Avenue Grant Permission 4. Nazeing 42 (With Conditions) Essex EN10 6RD EPF/2586/15 Di Rosa Garden Centre Tylers Road Grant Permission 5. Roydon 46 Harlow (With Conditions) Essex CM19 5LJ EPF/2777/15 The Briars Old House Lane Grant Permission 6. Roydon 54 Harlow (With Conditions) Essex CM19 5DN EPF/2809/15 Dallance Farm Breach Barns Lane 7. Waltham Abbey Refuse Permission 62 Essex EN9 2AD Epping Forest District Council 123 Agenda1 Item Number 1 0 4 .2 4 m 4 1 2 1 TCB 1 Conifers 9 14 13 LB Midway 6 Shelter Clevedon 7 4 4 1 EFDC 1 SE 9 9 LO Newfields 1 1 N C 4 4 0 EE 0 3 R 3 9 G 9 D 3 3 8 r 8 a i n 3 3 7 7 Tudor Rose 3 3 6 6 4 4 6 6 4 4 2 2 3 3 El Sub Sta 2 2 2 2 9 9 3 3 3 3 Rose Bungalow 8 8 2 2 t rof C lm E Three Gates lms Noe um Lind lose C Eden Greenleaf 4 dge Cottage e Lo ourn Fairb 18 Pump 1 NE 2 S LA 30 TER CAR 2 8 8 W 1 1 a v e r 7 7 U le p y la P n U d M 99.4m s P Cair L nsmo A re H N ig E h la n d Chestnut Cottage Goodrington s C H E Greenway S 4 4 The T N Hebrides U Long View Epping Upland T W EFDCA C of E L K Primary School Lincombe B 1 1 Plashetts 1 8 Nevin 1 Unauthorised reproduction infringes Crown Copyright and may lead to Application Number: EPF/1593/15 prosecution or civil proceedings. -

Letter to Residents

SMO3 Ringway Jacobs | Essex County Council Unit 36 Childerditch Industrial Estate Brentwood CM13 3HD Our Ref: DM/304/22 Date: 17 December 2015 Dear Sir/Madam PROPOSED TRAFFIC REGULATION ORDERS A1168 Rectory Lane/Chigwell Lane, Borders Lane, The Broadway, Barrington Green, Langston Road and A113 Abridge Road, Loughton, Essex Planning permission was granted by Epping Forest District Council for the redevelopment of the Council Depot site beside Langston Road, Loughton as a shopping park. This requires highway improvement works in the vicinity of the proposed shopping park which include the provisions of new pedestrian crossing facilities, replacement of mini roundabouts with signal controlled junctions, upgrading of the street lighting system and increasing the number of lanes along the main road. By introducing these measures traffic flow and connectivity between the M11 junction and Loughton should improve. The changes also endeavour to provide safer crossing points for the high level of pedestrian traffic to/from Debden Station, Epping Forest College and The Broadway shopping area. Legal orders called Traffic Regulation Orders are required to implement these proposals and this is an invitation for you to view the changes and make comments. Enclosed with this letter are four drawings illustrating these proposals. On the following two pages, we have given you the detailed information. Due to the complex nature of the proposals, the changes are summarised as follows: (A) Pedestrian crossing proposals (B) Waiting restriction proposals (C) -

Meeting Places and Gradients

Meeting places There is parking at all the meeting places but this is limited at busy times such as weekends so please arrive early. We are sorry that we cannot provide transport. LVRPA = Lee Valley Regional Park Authority. CPT = Car Parking Tariff, pay by phone or online at home. Walk 1 Around Waltham Abbey (CPT) ( Abbey View, Waltham Abbey, Essex. EN9 1XQ) Level A 0.8 mile. (1.6 miles twice) Gardens, Abbey church and stream. Meet at LVRPA Abbey Gardens car park. Surface Mostly tarmac, hard paths and some grass. Footwear Dry shoes. Gradient All on the flat. Walk 2 Old River Lea Loop (CPT) ( Stubbins Hall Lane, Crooked Mile, Waltham Abbey, Essex. EN9 2EF Continue through carpark towards sailing club and you will see a large parking area on the left) Level A 1.8 miles. Riverside. Meet at LVRPA Fishers Green overflow car park, Waltham Abbey.Surface Tarmac, gravel and earth paths. Footwear Dry shoes. Gradient All on the flat. Walk 3 Seventy Acre Lake (CPT) (Stubbins Hall Lane, Crooked Mile, Waltham Abbey, Essex. EN9 2EF) Level A 1.8 miles. Lakeside. Meet at LVRPA Fishers Green car park nr. Waltham Abbey Surface Tarmac and gravel. Footwear Dry shoes.Gradient All on the flat apart from a very short slope up to the river bridge. Walk 4 Cheshunt Lake (CPT) (Fishers Green Lane, Waltham Abbey, Essex. EN9 2ED) Level A 2.25 miles. Lake and River. Meet at LVRPA Hooks Marsh car park, nr Waltham Abbey. Surface Tarmac and gravel paths. Footwear Dry shoes. Gradient All on the flat apart from a very short slope up to the river bridge.