Screening and Watching Nostalgia an Analysis of Nostalgic Television Fiction and Its Reception in Germany and Spain

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Development of Digital TV in Europe 2000 Report

Development of Digital TV in Europe 2000 Report Spain Prepared by IDATE Final version – December 2000 Development of digital TV in Spain Contents 1DIGITAL TV MARKET OVERVIEW ......................................... 3 1.1 Roll-out of digital services................................................... 3 1.2 Details of the services ....................................................... 8 1.3 Operators and market structure............................................ 13 1.4 Technical issues............................................................ 15 1.5 Conclusion................................................................. 18 2KEY FIGURES FOR THE SPANISH MARKET ................................19 2.1 Country fundamentals ..................................................... 19 2.2 Equipment................................................................. 19 2.3 Television market estimates ................................................ 20 2.4 Details of the subscription-TV market ...................................... 20 IDATE 2 Development of digital TV in Spain 1 Digital TV market overview 1.1 Roll-out of digital services 1.1.1 Satellite digital services Two satellite-based digital TV platforms were operating in the Spanish market in 2000: Canal Satélite Digital (launched February 1997; via Astra) and Distribuidora de Televisión Digital - Vía Digital (launched September 1997; via Hispasat). They continue to experience strong growth with a combined 1.500.000 subscribers by mid 2000. The satellite digital market has been boosted by -

Los Archivos Televisivos Españoles, ¿ Patrimonio O Tienda De Recuerdos ?

Los archivos televisivos españoles, ¿ Patrimonio o tienda de recuerdos ? Jean-Stéphane Duran Froix CREC-TIL Université de Bourgogne in La télévision espagnole en point de mire, publication du CREC, http://crec- paris3.fr/publication/la-television- espagnole-en-point-de-mire ISSN 1773-0023, 2102, p. 12- 57. Los archivos televisivos españoles, ¿ Patrimonio o tienda de recuerdos ? La creación audiovisual es el último tipo de producción del genio humano en ser integrada, en un número creciente de países, al patrimonio histórico. Este proceso de reconocimiento se inició en Viena, en 1899, cuando la Academia Austríaca de Ciencias se dotó de un archivo de fonogramas que elevaba los sonidos al rango de bienes culturales, hasta entonces exclusivamente reservado a las obras literarias, líricas, plásticas o arquitectónicas. A pesar de la concomitancia en la divulgación de las nuevas técnicas de representación de lo existente, las imágenes (ya sean fijas o en movimiento) siguieron derroteros más largos y tortuosos antes de conseguir tamaña valorización. La fotografía no empezó a ser considerada como objeto cultural hasta el advenimiento del pictorialismo, cincuenta años después de que surgiera el daguerrotipo. Debido a su evidente parentesco1 con la pintura, la imagen estática comenzó a adquirir valor patrimonial más como producto artístico que como técnica o documento. Si esta estrecha relación con el Arte la incluía entre las manifestaciones existentes de la belleza, comprometía paradójicamente su vocación inicial de fiel reflejo de la realidad. Contrariamente al caso de la reproducción sonora y pese al éxito del retratismo durante la segunda mitad del siglo XIX, hay que esperar a la Iª Guerra Mundial y a la generalización del fotoperiodismo en los años 1920, para que se fije su dimensión testimonial que se produce al mismo tiempo que se convierte en el mejor soporte propagandístico. -

Be Sure to MW-Lv/Ilci

Page 12 The Canadian Statesman. Bowmanville. April 29, 1998 Section Two From page 1 bolic vehicle taking its riders into other promised view from tire window." existences. Fit/.patriek points to a tiny figure peer In the Attic ing out of an upstairs window on an old photograph. He echoes that image in a Gwen MacGregor’s installation in the new photograph, one he took looking out attic uses pink insulation, heavy plastic of the same window with reflection in the and a very slow-motion video of wind glass. "I was playing with the idea of mills along with audio of a distant train. absence and presence and putting shifting The effect is to link the physical elements images into the piece." of the mill with the artist’s own memories growing up on the prairies. Train of Thought In her role as curator for the VAC, Toronto area artists Millie Chen and Rodgers attempts to balance the expecta Evelyn Michalofski collaborated on the tions of serious artists in the community Millery, millery, dustipoll installation with the demands of the general popula which takes its title from an old popular tion. rhyme. “There has to be a cultural and intel TeddyBear Club Holds Workshop It is a five-minute video projected onto lectual feeding," she says, and at the same Embroidered noses, button eyes, fuzzy cars, and adorable faces arc the beginnings of a beautiful teddy bear. three walls in a space where the Soper time, we have to continue to offer the So say the members of the Bowmanville Teddy Bear Club. -

Press Release

PRESS RELEASE Collaboration between AGF and YouTube provides new evidence of the relevance of video in the German media landscape Frankfurt/Hamburg, Mar. 6th, 2019 — For the first time, the AGF Videoforschung (AGF) and YouTube published the results of their cooperation. Their collaboration started more than three years ago. The aim of this cooperation is to map the additional use of video through other platforms within the framework of the AGF convergence standard. The results for the observation period show that — with an average daily viewing time of 267 minutes for persons 18 years and older — the relevance of video in Germany is unbroken! During the study period, traditional linear TV usage averaged 232 minutes per day. Plus 35 minutes of streaming usage, mostly through mobile devices (60%). "It is a remarkable milestone for AGF's video research to have reached the current level together with YouTube. Everyone involved knows that we need to work continuously on this internationally unique project to best reflect the differentiated use of the platform in this dynamically changing technological environment. AGF's goal is to identify YouTube as a reliable, transparent partner in the AGF system, in line with the common market standard", said AGF Managing Director Kerstin Niederauer-Kopf. Dirk Bruns, Head of Video Sales, Google Germany: "We are very proud to be able to present the first results together with AGF Videoforschung and hope that industry representatives from other countries will follow the example of AGF. Google has long been committed to transparent measurement. And the presented data highlights the relevance of the YouTube platform for users, the advertising industry, and our content partners." 1 YouTube as platform in the AGF system Since April 2015, AGF and YouTube have collaborated intensively with the common goal of integrating the YouTube platform into the AGF system. -

TV TV Sender 20 ARD RTL Comedy Central RTL2 DAS VIERTE SAT.1

TV Anz. Sender TV Sender 20 ARD (national) RTL Comedy Central (01/2009) RTL2 DAS VIERTE (1/2006) SAT.1 DMAX (1/2007) Sixx (01/2012) EuroSport (nur Motive) Sport 1 (ehemals DSF) Kabel Eins Super RTL N24 Tele 5 (1/2007) Nickelodeon (ehemals Nick) VIVA N-TV VOX Pro Sieben ZDF Gesamtergebnis TV Sender 20 Radio Anz. Sender Radio Sender 60 104,6 RTL MDR 1 Sachsen-Anhalt 94,3 rs2 MDR1 Thüringen Antenne Bayern NDR 2 Antenne Brandenburg Oldie 95 Antenne Mecklenburg-Vorpommern Planet Radio Antenne Thüringen R.SH Radio Schleswig-Holstein Bayern 1 Radio Berlin 88,8 Bayern 2 Radio Brocken Bayern 3 Radio Eins Bayern 4 Radio FFN Bayern 5 Radio Hamburg Bayern Funkpaket Radio Nora BB Radio Radio NRW Berliner Rundfunk 91!4 Radio PSR big FM Hot Music Radio Radio SAW Bremen 1 Radio-Kombi Baden Württemberg Bremen 4 RPR 1. Delta Radio Spreeradio Eins Live SR 1 Fritz SR 3 Hit-Radio Antenne Star FM Hit-Radio FFH SWR 1 Baden-Württemberg (01/2011) HITRADIO RTL Sachsen SWR 1 Rheinland-Pfalz HR 1 SWR 3 HR 3 SWR 4 Baden-Württemberg (01/2011) HR 4 SWR 4 Rheinland-Pfalz Inforadio WDR 2 Jump WDR 4 KISS FM YOU FM Landeswelle Thüringen MDR 1 Sachsen Gesamtergebnis Radio Sender 60 Plakat Anz. Städte Städte 9 Berlin Frankfurt Hamburg Hannover Karlsruhe Köln Leipzig München Halle Gesamtergebnis Städte 9 Seite 1 von 19 Presse ZIS Anz. Titel ZIS Anz. Titel Tageszeitungen (TZ) 150 Tageszeitungen (TZ) 150 Regionalzeitung 113 Regionalzeitung 113 BaWü 16 Hamburg 3 Aalener Nachrichten/Schwäbische Zeitung 100111 Hamburger Abendblatt 101659 Badische Neueste Nachrichten 100121 Hamburger -

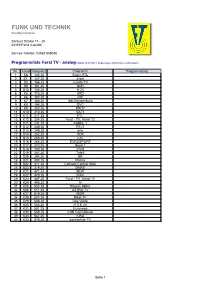

FUNK UND TECHNIK Breitbandnetze

FUNK UND TECHNIK Breitbandnetze Sorauer Straße 17 - 25 03149 Forst (Lausitz) Service-Telefon: 03562 959030 Programmliste Forst TV - analog (Stand: 26.07.2013, Änderungen und Irrtümer vorbehalten) Nr. Kanal Frequenz Programm Programmplatz 1 S6 140,25 Super-RTL 2 S7 147,25 3-sat 3 S8 154,25 Juwelo TV 4 S9 161,25 NDR 5 S10 168,25 N-24 6 K5 175,25 ARD 7 K6 182,25 ZDF 8 K7 189,25 rbb Brandenburg 9 K8 196,25 QVC 10 K9 203,25 PRO7 11 K10 210,25 SAT1 12 K11 217,25 RTL 13 K12 224,25 Forst - TV, Kanal 12 14 S11 231,25 KABEL 1 15 S12 238,25 RTL2 16 S13 245,25 arte 17 S14 252,25 VOX 18 S15 259,25 n-tv 19 S16 266,25 EUROSPORT 20 S17 273,25 Sport 1 21 S18 280,25 VIVA 22 S19 287,25 Tele5 23 S20 294,25 BR 24 S21 303,25 Phönix 25 S22 311,25 Comedy Central /Nick 26 S23 319,25 DMAX 27 K21 471,25 MDR 28 K22 479,25 SIXX 29 K23 487,25 Forst - TV, Kanal 12 30 K24 495,25 hr 31 K25 503,25 Bayern Alpha 32 K26 511,25 ASTRO TV 33 K27 519,25 WDR 34 K28 527,25 Bibel TV 35 K29 535,25 Das Vierte 36 K30 543,25 H.S.E.24 37 K31 551,25 Euronews 38 K32 559,25 CNN International 39 K33 567,25 KIKA 40 K34 575,25 sonnenklar TV Seite 1 Programmliste Forst TV - digital (Stand: 26.07.2013, Änderungen vorbehalten) Nr. -

Informe Anual Y De Responsabilidad Corporativa 2012

ATRESMEDIA 2012 ANNUAL AND CORPORATE RESPONSIBILITY REPORT THE YEAR’S HIGHLIGHts 16 2012 Milestones Success in the integration of laSexta On 1 October, the merger took place between Antena 3 and laSexta, a successful process in which the former laSexta shareholders take an initial stake of 7% in the new company and an additional stake of up to 7%, phased in gradually and in function of compliance during the 2012-2016 period with a series of objectives related to the results of the new Group. With the incorporation of the television offering oflaSexta , Atresmedia Televisión adds to its outstanding presence in other markets (radio, advertising or cinema) a leading proposal in the television business: in total eight channels (Antena 3, laSexta, Neox, Nova, Nitro, xplora, laSexta3TODOCINE and Gol TV, the latter un- der a lease arrangement), which consolidates the Company as the leading com- munication group. Antena 3, the best year of its history Since the birth of Antena 3 until the present, the Company has been expand- ing and consolidating its business areas. Probably 2012 was the best year in the Group’s history despite the highly complex economic climate in which it has had to operate. Its family television model, based on quality and variety of contents, was applauded by the audience, by the audiovisual industry itself and by the ad- vertisers. ATRESMEDIA 2012 ANNUAL AND CORPORATE RESPONSIBILITY REPORT THE YEAR’S HIGHLIGHts 17 Antena 3 climbs to second position Tu Cara me Suena, El Hormiguero 3.0 In 2012, Antena 3 attained second position among the audience and was the only and Con el Culo leading television channel which succeeded in expanding in the year, to 12.5% of al Aire. -

Quickline Senderangebot Replay + Plus Sports Entertainment Adult Sprachpakete

Quickline Senderangebot Replay + Plus Sports Entertainment Adult Sprachpakete Deutschsprachige Sender 55 Channel 55 1 SRF 1 HD 56 Servus TV HD 2 SRF zwei HD 61 Comedy Central HD / 3 SRF info HD VIVA CH HD 4 MySports HD 62 MTV CH HD 9 3+ HD 63 Nickelodeon HD 10 4+ HD 64 Super RTL HD* + 11 5+ HD 65 Disney Channel 13 S1 HD 66 KiKA HD 14 TV24 HD 68 ONE HD 15 Puls 8 HD 69 zdf_neo HD 16 Star TV HD 70 ZDFinfo HD 18 CHTV HD 72 ORF III HD 19 TV25 HD 73 ARD-alpha 21 Das Erste HD 74 PHOENIX HD 22 ZDF HD 327 DW-TV + 23 ORF eins HD 76 tagesschau24 HD 24 ORF 2 HD 77 n-tv HD* + 25 RTL HD* + 78 N24 HD 26 SAT.1 HD* + 79 euronews HD 27 ProSieben HD* + 97 ULS Network HD 28 VOX HD* + 98 Schweiz5 29 RTL 2 HD* + 115 TELE 5 + 30 kabel eins HD* + 124 Anixe HD Serie + 31 SWR BW HD 133 Welt der Wunder + 32 BR Süd HD 214 Sky Sport News HD + 33 WDR Köln HD 152 K-TV 34 hr-fernsehen HD 153 Bibel TV HD 35 MDR S-Anhalt HD 161 Alpen-Welle TV HD 36 rbb Berlin HD 170 Deluxe Music + 37 NDR FS NDS HD Sport 38 3sat HD 200 MySports HD 39 arte HD 201 Ab Sommer 2017 finden Sie 43 DMAX HD – hier die neuen Sportsender 44 RTLNITRO HD* + 209 von MySports 45 ProSieben MAXX HD* + 211 Eurosport 1 46 kabel eins Doku + 212 sport1 HD 48 RTLplus + 215 Eurosport 1 HD 49 SAT.1 Gold HD* + 216 Eurosport 2 HD 50 SIXX HD* + 217 sport1+ HD 51 TLC HD 218 sportdigital HD 220 Motorvision Musik 221 Motorsport TV HD 290 MTV Brand New + 222 sport 1 US HD 291 MTV Music + 223 Extreme Sports Channel 292 MTV Dance + 293 MTV Live HD + Adult 294 iConcerts HD + 230 Blue Hustler 295 VH1 Classic + 231 Penthouse -

Exposing Corruption in Progressive Rock: a Semiotic Analysis of Gentle Giant’S the Power and the Glory

University of Kentucky UKnowledge Theses and Dissertations--Music Music 2019 EXPOSING CORRUPTION IN PROGRESSIVE ROCK: A SEMIOTIC ANALYSIS OF GENTLE GIANT’S THE POWER AND THE GLORY Robert Jacob Sivy University of Kentucky, [email protected] Digital Object Identifier: https://doi.org/10.13023/etd.2019.459 Right click to open a feedback form in a new tab to let us know how this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Sivy, Robert Jacob, "EXPOSING CORRUPTION IN PROGRESSIVE ROCK: A SEMIOTIC ANALYSIS OF GENTLE GIANT’S THE POWER AND THE GLORY" (2019). Theses and Dissertations--Music. 149. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/music_etds/149 This Doctoral Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Music at UKnowledge. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations--Music by an authorized administrator of UKnowledge. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STUDENT AGREEMENT: I represent that my thesis or dissertation and abstract are my original work. Proper attribution has been given to all outside sources. I understand that I am solely responsible for obtaining any needed copyright permissions. I have obtained needed written permission statement(s) from the owner(s) of each third-party copyrighted matter to be included in my work, allowing electronic distribution (if such use is not permitted by the fair use doctrine) which will be submitted to UKnowledge as Additional File. I hereby grant to The University of Kentucky and its agents the irrevocable, non-exclusive, and royalty-free license to archive and make accessible my work in whole or in part in all forms of media, now or hereafter known. -

The Beard Is a Bloody Bother"

The beard is a bloody bother" Except for the makeup, Edward Mulhare enjoys impersonating a ghost. By Burt Prelutsky TV Guide, May 17, 1969 If Rex Harrison ever gets the funny feeling he's being followed, it isn't paranoia it's Edward Mulhare. In 1957, just 11 months after "My Fair Lady" opened on Broadway. Harrison bowed out. Mulhare took over in the role of Prof. Henry Higgins and spent three years trying to straighten out Eliza Doolittle's diction. Then this past season, some 21 years after the movie "The Ghost and Mrs. Muir" was released, the story popped up again as the vehicle for a TV series. Again Mulhare was in for Harrison. They aren't, in fact, all that much alike. Harrison bites off his lines as though he could taste them, and spits them out like bitter seeds. Mulhare is not nearly so brittle or waspish as Rex. Whereas Rex is regal and aloof, Edward is about as standoffish as a teddy bear. Or, as Mulhare sums it up: "We're both tall and long-faced and we speak standard English. I've always liked the light style of acting, and Rex, of course, is a past master of it But, otherwise, we are not at all similar." Like Captain Gregg. the ghost he portrays, Mulhare. 46, has never married. Unlike the Captain, "I have nothing against marriage; I've just never gotten around to it." Why not? Even Mulhare doesn't know, or isn't saying. It surely isn't for lack of opportunity As the No. -

Claudia Richter, Photos/Layout: Claudia Richter

No Fear of a blank interview By Uwe Häberle And Claudia Richter, Photos/Layout: Claudia Richter During the „Fear of a blank planet“ autumn tour 2007 Steven Wilson was ready to answer the questions of the editors from www.Voyage-PT.de on 13th Novem- ber 2007 at the „LKA“ in Stuttgart, despite the fact that there is no massive promotion effect for the band to be expected from a fan website as e.g. from re- spective music magazines or radio stations. Mr. Wilson presented himself as a deeply grateful conversational partner. And if he enjoyed the questions than the coverage of his answers exceeded the questions many times over. Steven allo- wed fascinating insights into his intellectual world, which significantly influences his creativity. And en passant he proved that he still is a down-to-earth person. There is probably nothing a blank planet“ tour in au- take several pictures. Our Well prepared we came on better for a diehard Porcu- tumn 2007 we retried our main goal was to conduct the dot to the „LKA“ to fire pine Tree fan (beside the miss out chance again and an interview that steps be- our questions at Steven. live events of course ) as to started a new inquiry at the yond the usual questions Not an easy undertaking, ask Steven Wilson exactly record label „Roadrunner“. and that addresses as- as it all causes a great those questions that you „Roadrunner“ arranged pects on which Steven, in excitement on ourselves always wanted to ask. Du- an interview appointment our humble opinion, never that we had to keep under ring the Blackfield tour in on the 13th of November commented on. -

Karaoke Mietsystem Songlist

Karaoke Mietsystem Songlist Ein Karaokesystem der Firma Showtronic Solutions AG in Zusammenarbeit mit Karafun. Karaoke-Katalog Update vom: 13/10/2020 Singen Sie online auf www.karafun.de Gesamter Katalog TOP 50 Shallow - A Star is Born Take Me Home, Country Roads - John Denver Skandal im Sperrbezirk - Spider Murphy Gang Griechischer Wein - Udo Jürgens Verdammt, Ich Lieb' Dich - Matthias Reim Dancing Queen - ABBA Dance Monkey - Tones and I Breaking Free - High School Musical In The Ghetto - Elvis Presley Angels - Robbie Williams Hulapalu - Andreas Gabalier Someone Like You - Adele 99 Luftballons - Nena Tage wie diese - Die Toten Hosen Ring of Fire - Johnny Cash Lemon Tree - Fool's Garden Ohne Dich (schlaf' ich heut' nacht nicht ein) - You Are the Reason - Calum Scott Perfect - Ed Sheeran Münchener Freiheit Stand by Me - Ben E. King Im Wagen Vor Mir - Henry Valentino And Uschi Let It Go - Idina Menzel Can You Feel The Love Tonight - The Lion King Atemlos durch die Nacht - Helene Fischer Roller - Apache 207 Someone You Loved - Lewis Capaldi I Want It That Way - Backstreet Boys Über Sieben Brücken Musst Du Gehn - Peter Maffay Summer Of '69 - Bryan Adams Cordula grün - Die Draufgänger Tequila - The Champs ...Baby One More Time - Britney Spears All of Me - John Legend Barbie Girl - Aqua Chasing Cars - Snow Patrol My Way - Frank Sinatra Hallelujah - Alexandra Burke Aber Bitte Mit Sahne - Udo Jürgens Bohemian Rhapsody - Queen Wannabe - Spice Girls Schrei nach Liebe - Die Ärzte Can't Help Falling In Love - Elvis Presley Country Roads - Hermes House Band Westerland - Die Ärzte Warum hast du nicht nein gesagt - Roland Kaiser Ich war noch niemals in New York - Ich War Noch Marmor, Stein Und Eisen Bricht - Drafi Deutscher Zombie - The Cranberries Niemals In New York Ich wollte nie erwachsen sein (Nessajas Lied) - Don't Stop Believing - Journey EXPLICIT Kann Texte enthalten, die nicht für Kinder und Jugendliche geeignet sind.