Vulvar Cancer (Squamous Cell Carcinoma)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Genetic Markers in Lung Cancer Diagnosis: a Review

International Journal of Molecular Sciences Review Genetic Markers in Lung Cancer Diagnosis: A Review Katarzyna Wadowska 1 , Iwona Bil-Lula 1 , Łukasz Trembecki 2,3 and Mariola Sliwi´ ´nska-Mosso´n 1,* 1 Department of Medical Laboratory Diagnostics, Division of Clinical Chemistry and Laboratory Haematology, Wroclaw Medical University, 50-556 Wroclaw, Poland; [email protected] (K.W.); [email protected] (I.B.-L.) 2 Department of Radiation Oncology, Lower Silesian Oncology Center, 53-413 Wroclaw, Poland; [email protected] 3 Department of Oncology, Faculty of Medicine, Wroclaw Medical University, 53-413 Wroclaw, Poland * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +48-71-784-06-30 Received: 1 June 2020; Accepted: 25 June 2020; Published: 27 June 2020 Abstract: Lung cancer is the most often diagnosed cancer in the world and the most frequent cause of cancer death. The prognosis for lung cancer is relatively poor and 75% of patients are diagnosed at its advanced stage. The currently used diagnostic tools are not sensitive enough and do not enable diagnosis at the early stage of the disease. Therefore, searching for new methods of early and accurate diagnosis of lung cancer is crucial for its effective treatment. Lung cancer is the result of multistage carcinogenesis with gradually increasing genetic and epigenetic changes. Screening for the characteristic genetic markers could enable the diagnosis of lung cancer at its early stage. The aim of this review was the summarization of both the preclinical and clinical approaches in the genetic diagnostics of lung cancer. The advancement of molecular strategies and analytic platforms makes it possible to analyze the genome changes leading to cancer development—i.e., the potential biomarkers of lung cancer. -

Ovarian Cancer and Cervical Cancer

What Every Woman Should Know About Gynecologic Cancer R. Kevin Reynolds, MD The George W. Morley Professor & Chief, Division of Gyn Oncology University of Michigan Ann Arbor, MI What is gynecologic cancer? Cancer is a disease where cells grow and spread without control. Gynecologic cancers begin in the female reproductive organs. The most common gynecologic cancers are endometrial cancer, ovarian cancer and cervical cancer. Less common gynecologic cancers involve vulva, Fallopian tube, uterine wall (sarcoma), vagina, and placenta (pregnancy tissue: molar pregnancy). Ovary Uterus Endometrium Cervix Vagina Vulva What causes endometrial cancer? Endometrial cancer is the most common gynecologic cancer: one out of every 40 women will develop endometrial cancer. It is caused by too much estrogen, a hormone normally present in women. The most common cause of the excess estrogen is being overweight: fat cells actually produce estrogen. Another cause of excess estrogen is medication such as tamoxifen (often prescribed for breast cancer treatment) or some forms of prescribed estrogen hormone therapy (unopposed estrogen). How is endometrial cancer detected? Almost all endometrial cancer is detected when a woman notices vaginal bleeding after her menopause or irregular bleeding before her menopause. If bleeding occurs, a woman should contact her doctor so that appropriate testing can be performed. This usually includes an endometrial biopsy, a brief, slightly crampy test, performed in the office. Fortunately, most endometrial cancers are detected before spread to other parts of the body occurs Is endometrial cancer treatable? Yes! Most women with endometrial cancer will undergo surgery including hysterectomy (removal of the uterus) in addition to removal of ovaries and lymph nodes. -

The Cyclist's Vulva

The Cyclist’s Vulva Dr. Chimsom T. Oleka, MD FACOG Board Certified OBGYN Fellowship Trained Pediatric and Adolescent Gynecologist National Medical Network –USOPC Houston, TX DEPARTMENT NAME DISCLOSURES None [email protected] DEPARTMENT NAME PRONOUNS The use of “female” and “woman” in this talk, as well as in the highlighted studies refer to cis gender females with vulvas DEPARTMENT NAME GOALS To highlight an issue To discuss why this issue matters To inspire future research and exploration To normalize the conversation DEPARTMENT NAME The consensus is that when you first start cycling on your good‐as‐new, unbruised foof, it is going to hurt. After a “breaking‐in” period, the pain‐to‐numbness ratio becomes favourable. As long as you protect against infection, wear padded shorts with a generous layer of chamois cream, no underwear and make regular offerings to the ingrown hair goddess, things are manageable. This is wrong. Hannah Dines British T2 trike rider who competed at the 2016 Summer Paralympics DEPARTMENT NAME MY INTRODUCTION TO CYCLING Childhood Adolescence Adult Life DEPARTMENT NAME THE CYCLIST’S VULVA The Issue Vulva Anatomy Vulva Trauma Prevention DEPARTMENT NAME CYCLING HAS POSITIVE BENEFITS Popular Means of Exercise Has gained popularity among Ideal nonimpact women in the past aerobic exercise decade Increases Lowers all cause cardiorespiratory mortality risks fitness DEPARTMENT NAME Hermans TJN, Wijn RPWF, Winkens B, et al. Urogenital and Sexual complaints in female club cyclists‐a cross‐sectional study. J Sex Med 2016 CYCLING ALSO PREDISPOSES TO VULVAR TRAUMA • Significant decreases in pudendal nerve sensory function in women cyclists • Similar to men, women cyclists suffer from compression injuries that compromise normal function of the main neurovascular bundle of the vulva • Buller et al. -

DCIS): Pathological Features, Differential Diagnosis, Prognostic Factors and Specimen Evaluation

Modern Pathology (2010) 23, S8–S13 S8 & 2010 USCAP, Inc. All rights reserved 0893-3952/10 $32.00 Ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS): pathological features, differential diagnosis, prognostic factors and specimen evaluation Sarah E Pinder Breast Research Pathology, Research Oncology, Division of Cancer Studies, King’s College London, Guy’s Hospital, London, UK Ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS) is a heterogeneous, unicentric precursor of invasive breast cancer, which is frequently identified through mammographic breast screening programs. The lesion can cause particular difficulties for specimen handling in the laboratory and typically requires even more diligent macroscopic assessment and sampling than invasive disease. Pitfalls and tips for macroscopic handling, microscopic diagnosis and assessment, including determination of prognostic factors, such as cytonuclear grade, presence or absence of necrosis, size of the lesion and distance to margins are described. All should be routinely included in histopathology reports of this disease; in order not to omit these clinically relevant details, synoptic reports, such as that produced by the College of American Pathologists are recommended. No biomarkers have been convincingly shown, and validated, to predict the behavior of DCIS till date. Modern Pathology (2010) 23, S8–S13; doi:10.1038/modpathol.2010.40 Keywords: ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS); breast cancer; histopathology; prognostic factors Ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS) is a malignant, lesions, a good cosmetic result can be obtained by clonal proliferation of cells growing within the wide local excision. Recurrence of DCIS generally basement membrane-bound structures of the breast occurs at the site of previous excision and it is and with no evidence of invasion into surrounding therefore better regarded as residual disease, as stroma. -

Pregnancy and Cesarean Delivery After Multimodal Therapy for Vulvar Carcinoma: a Case Report

MOLECULAR AND CLINICAL ONCOLOGY 5: 583-586, 2016 Pregnancy and cesarean delivery after multimodal therapy for vulvar carcinoma: A case report KUNIAKI TORIYABE1,2, HARUKI TANIGUCHI2, TOKIHIRO SENDA2,3, MASAKO NAKANO2, YOSHINARI KOBAYASHI2, MIHO IZAWA2, HIROHIKO TANAKA2, TETSUO ASAKURA2, TSUTOMU TABATA1 and TOMOAKI IKEDA1 1Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Mie University Graduate School of Medicine, Tsu, Mie 514-8507; 2Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Mie Prefectural General Medical Center, Yokkaichi, Mie 510-8561; 3Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Kinan Hospital, Mihama, Mie 519-5293, Japan Received November 4, 2015; Accepted September 12, 2016 DOI: 10.3892/mco.2016.1021 Abstract. Reports of pregnancy following treatment for vulvectomy, may have an increased incidence of caesarean vulvar carcinoma are extremely uncommon, as the main delivery (2). In the literature, vulvar scarring following radical problem of subsequent pregnancy is vulvar scarring following vulvectomy was the major reason for pregnant women under- radical surgery. We herein report the case of a patient who was going caesarean section (2-7). To date, no cases of pregnancy diagnosed with stage I squamous cell carcinoma of the vulva following vulvar carcinoma have been reported in patients at the age of 17 years and was treated with multimodal therapy, who had undergone surgery and radiotherapy. including neoadjuvant chemotherapy, wide local excision with We herein describe a case in which caesarean section was bilateral inguinal lymph node dissection and adjuvant radio- performed due to the presence of extensive vulvar scarring therapy. The patient became pregnant spontaneously 9 years following multimodal therapy for vulvar carcinoma, including after her initial diagnosis and the antenatal course was good, chemotherapy, surgery and radiotherapy. -

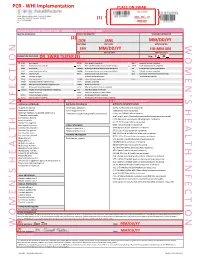

Womens Health Requisition Forms

PCR - WHI Implementation PLACE ON SWAB 10854 Midwest Industrial Blvd. St. Louis, MO 63132 MM DD YY Phone: (314) 200-3040 | Fax (314) 200-3042 (1) CLIA ID #26D0953866 JANE DOE v3 PCR MOLECULAR REQUISITION - WOMEN'S HEALTH INFECTION PRACTICE INFORMATION PATIENT INFORMATION *SPECIMEN INFORMATION (2) DOE JANE MM/DD/YY LAST NAME FIRST NAME DATE COLLECTED W O M E ' N S H E A L T H I F N E C T I O N SSN MM/DD/YY HH:MM AM SSN DATE OF BIRTH TIME COLLECTED REQUESTING PHYSICIAN: DR. SWAB TESTER (3) Sex: F X M (4) Diagnosis Codes X N76.0 Acute vaginitis B37.49 Other urogenital candidiasis A54.9 Gonococcal infection, unspecified N76.1 Subacute and chronic vaginitis N89.8 Other specified noninflammatory disorders of vagina A59.00 Urogenital trichomoniasis, unspecified N76.2 Acute vulvitis O99.820 Streptococcus B carrier state complicating pregnancy A64 Unspecified sexually transmitted disease N76.3 Subacute and chronic vulvitis O99.824 Streptococcus B carrier state complicating childbirth A74.9 Chlamydial infection, unspecified N76.4 Abscess of vulva B95.1 Streptococcus, group B, as the cause Z11.3 Screening for infections with a predmoninantly N76.5 Ulceration of vagina of diseases classified elsewhere sexual mode of trasmission N76.6 Ulceration of vulva Z22.330 Carrier of group B streptococcus Other: N76.81 Mucositis(ulcerative) of vagina and vulva N70.91 Salpingitis, unspecified N76.89 Other specified inflammation of vagina and vulva N70.92 Oophoritis, unspecified N95.2 Post menopausal atrophic vaginitis N71.9 Inflammatory disease of uterus, unspecified -

Female Perineum Doctors Notes Notes/Extra Explanation Please View Our Editing File Before Studying This Lecture to Check for Any Changes

Color Code Important Female Perineum Doctors Notes Notes/Extra explanation Please view our Editing File before studying this lecture to check for any changes. Objectives At the end of the lecture, the student should be able to describe the: ✓ Boundaries of the perineum. ✓ Division of perineum into two triangles. ✓ Boundaries & Contents of anal & urogenital triangles. ✓ Lower part of Anal canal. ✓ Boundaries & contents of Ischiorectal fossa. ✓ Innervation, Blood supply and lymphatic drainage of perineum. Lecture Outline ‰ Introduction: • The trunk is divided into 4 main cavities: thoracic, abdominal, pelvic, and perineal. (see image 1) • The pelvis has an inlet and an outlet. (see image 2) The lowest part of the pelvic outlet is the perineum. • The perineum is separated from the pelvic cavity superiorly by the pelvic floor. • The pelvic floor or pelvic diaphragm is composed of muscle fibers of the levator ani, the coccygeus muscle, and associated connective tissue. (see image 3) We will talk about them more in the next lecture. Image (1) Image (2) Image (3) Note: this image is seen from ABOVE Perineum (In this lecture the boundaries and relations are important) o Perineum is the region of the body below the pelvic diaphragm (The outlet of the pelvis) o It is a diamond shaped area between the thighs. Boundaries: (these are the external or surface boundaries) Anteriorly Laterally Posteriorly Medial surfaces of Intergluteal folds Mons pubis the thighs or cleft Contents: 1. Lower ends of urethra, vagina & anal canal 2. External genitalia 3. Perineal body & Anococcygeal body Extra (we will now talk about these in the next slides) Perineum Extra explanation: The perineal body is an irregular Perineal body fibromuscular mass. -

Vaginal and Vulvar Cancer 10.1136/Ijgc-2020-ESGO.178

Int J Gynecol Cancer: first published as 10.1136/ijgc-2020-ESGO.177 on 4 December 2020. Downloaded from Abstracts 520 LONG TERM FOLLOW UP AFTER DIAGNOSIS OF Introduction/Background Since the introduction of the S2K GESTATIONAL TROPHOBLASTIC DISEASE AWMF guideline-based sentinel node biopsy technique in uni- focal vulvar cancer (diameter of <4 cm) and unsuspicious Pedro Corvelo Freitas, Beatriz Mira, António Guimarães, Ana Opinião, Hugo Nunes, Ana Francisca Jorge, Fátima Vaz, António Moreira. Instituto Português de Oncologia de Lisboa groin lymph nodes, the morbidity rate of patients has signifi- Francisco Gentil cantly decreased in Germany. The groin recurrence rate after IFL is vary from 0% to 5.8%, in contrast to 2.3% (95% CI, 10.1136/ijgc-2020-ESGO.176 0.6% to 5%) in unifocal vulvar cancer vs 3% (95% CI, 1% to 6%) in multifocal vulvar cancer after SLNB only, as sug- Introduction/Background The spectrum of Gestational tropho- gested in the GRoningen INternational Study on Sentinel blastic disease (GTD) ranges from pre-malignant conditions of node in Vulvar cancer (GROINSS-V-I) in 2008. Current guide- complete (CHM) and partial (PHM) hydatidiform moles to the lines suggest that in cases of metastasis of unilateral sentinel malignant invasive mole, choriocarcinoma (CC) and very rare lymph node (SLN) biopsy (B), groin node dissection, namely placental site trophoblastic tumour/epithelioid trophoblastic inguinofemoral lymphadenectomy (IFL), should be performed tumour (PSTT/ETT). Gestational trophoblastic neoplasia (GTN) bilaterally. However, a publication by Woelber et al. in Ger- are highly responsive to chemotherapy (CT) and with appropri- many and and Nica et al. -

Primary Immature Teratoma of the Thigh Fig

CORRESPONDENCE 755 8. Gray W, Kocjan G. Diagnostic Cytopathology. 2nd ed. London: Delete all that do not apply: Elsevier Health Sciences, 2003; 677. 9. Richards A, Dalrymple C. Abnormal cervicovaginal cytology, unsatis- Cervix, colposcopic biopsy/LLETZ/cone biopsy: factory colposcopy and the use of vaginal estrogen cream: an obser- vational study of clinical outcomes for women in low estrogen states. Diagnosis: NIL (No intraepithelial lesion WHO 2014) J Obstet Gynaecol Res 2015; 41: 440e4. LSIL (CIN 1 with HPV effect WHO 2014) 10. Darragh TM, Colgan TJ, Cox T, et al. The lower anogenital squamous HSIL (CIN2/3 WHO 2014) terminology standardization project for HPV-associated lesions: back- Squamous cell carcinoma ground and consensus recommendation from the College of American Immature squamous metaplasia Pathologists and the American Society for Colposcopy and Cervical Adenocarcinoma in situ (AIS, HGGA) e Adenocarcinoma Pathology. Arch Pathol Lab Med 2012; 136: 1267 97. Atrophic change 11. McCluggage WG. Endocervical glandular lesions: controversial aspects e Extending into crypts: Not / Idenfied and ancillary techniques. J Clin Pathol 2013; 56: 164 73. Epithelial stripping: Not / Present 12. World Health Organization (WHO). Comprehensive Cervical Cancer Invasive disease: Not / Idenfied / Micro-invasive Control: A Guide to Essential Practice. 2nd ed. Geneva: WHO, 2014. Depth of invasion: mm Transformaon zone: Not / Represented Margins: DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pathol.2019.07.014 Ectocervical: Not / Clear Endocervical: Not / Clear Circumferenal: Not / Clear p16 status: Negave / Posive Primary immature teratoma of the thigh Fig. 3 A proposed synoptic reporting format for pathologists reporting colposcopic biopsies and cone biopsies or LLETZ. Sir, Teratomas are germ cell tumours composed of a variety of HSIL, AIS, micro-invasive or more advanced invasive dis- somatic tissues derived from more than one germ layer 12 ease. -

Squamous Cell Carcinoma Arising in an Ovarian Mature Cystic Teratoma

Case Report Obstet Gynecol Sci 2013;56(2):121-125 http://dx.doi.org/10.5468/OGS.2013.56.2.121 pISSN 2287-8572 · eISSN 2287-8580 Squamous cell carcinoma arising in an ovarian mature cystic teratoma complicating pregnancy Nae-Ri Yun1, Jung-Woo Park1, Min-Kyung Hyun1, Jee-Hyun Park1, Suk-Jin Choi2, Eunseop Song1 Departments of 1Obstetrics and Gynecology and 2Pathology, Inha University College of Medicine, Incheon, Korea Mature cystic teratomas of the ovary (MCT) are usually observed in women of reproductive age with the most dreadful complication being malignant transformation which occurs in approximately 1% to 3% of MCTs. In this case report, we present a patient with squamous cell carcinoma which developed from a MCT during pregnancy. The patient was treated conservatively without adjuvant chemotherapy and was followed without evidence of disease for more than 60 months using conventional tools as well as positron emission tomography-computed tomography following the initial surgery. We report this case along with the review of literature. Keywords: Dermoid cyst; Malignant transformation; Observation; Positron emission tomography-computed tomography Introduction An 18 cm solid and cystic left ovarian mass with a smooth surface and two small right ovarian cysts were detected re- The incidence of adnexal masses during pregnancy is 1% to sulting in a laparotomy at 13 weeks of gestation and left sal- 9% [1]. Mature cystic teratomas (MCT) are common during pingo-oophorectomy and right ovarian cystectomy (Fig. 1C). pregnancy with the most dreadful complication being ma- The report of the frozen section from both tissues revealed lignant transformation which occurs in approximately 1% to MCT. -

Pembrolizumab in Vaginal and Vulvar Squamous Cell Carcinoma: a Case Series from a Phase II Basket Trial Jefrey A

www.nature.com/scientificreports OPEN Pembrolizumab in vaginal and vulvar squamous cell carcinoma: a case series from a phase II basket trial Jefrey A. How 1, Amir A. Jazaeri 1, Pamela T. Soliman1, Nicole D. Fleming1, Jing Gong2, Sarina A. Piha‑Paul2, Filip Janku 2, Bettzy Stephen 2 & Aung Naing 2* Vaginal and vulvar squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) are rare tumors that can be challenging to treat in the recurrent or metastatic setting. We present a case series of patients with vaginal or vulvar SCC who were treated with single‑agent pembrolizumab as part of a phase II basket clinical trial to evaluate efcacy and safety. Two cases of recurrent and metastatic vaginal SCC, with multiple prior lines of systemic chemotherapy and radiation, received pembrolizumab. One patient had signifcant reduction (81%) in target tumor lesions prior to treatment discontinuation at cycle 10 following confrmed progression of disease with new metastatic lesions (stable disease by irRECIST criteria). In contrast, the other patient with vaginal SCC discontinued treatment after cycle 3 due to disease progression. Both patients had PD‑L1 positive vaginal tumors and tolerated treatment well. One case of recurrent vulvar SCC with multiple surgical resections and prior progression on systemic carboplatin had a 30% reduction in her target tumor lesions following pembrolizumab treatment with a PD‑L1 positive tumor. Treatment was discontinued for grade 3 mucositis after cycle 5. Pembrolizumab may provide some clinical beneft to some patients with vaginal or vulvar SCC and is overall safe to utilize in this population. Future studies are needed to evaluate the efcacy of pembrolizumab in these rare tumor types and to identify predictive biomarkers of response. -

Influence of Age on Histologic Outcome of Cervical Intraepithelial Neoplasia

www.nature.com/scientificreports OPEN Infuence of age on histologic outcome of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia during observational Received: 10 May 2017 Accepted: 6 April 2018 management: results from large Published: xx xx xxxx cohort, systematic review, meta- analysis Christine Bekos1, Richard Schwameis1, Georg Heinze2, Marina Gärner1, Christoph Grimm1, Elmar Joura1,4, Reinhard Horvat3, Stephan Polterauer1,4 & Mariella Polterauer1 Aim of this study was to investigate the histologic outcome of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN) during observational management. Consecutive women with histologically verifed CIN and observational management were included. Histologic fndings of initial and follow-up visits were collected and persistence, progression and regression rates at end of observational period were assessed. Uni- and multivariate analyses were performed. A systematic review of the literature and meta-analysis was performed. In 783 women CIN I, II, and III was diagnosed by colposcopically guided biopsy in 42.5%, 26.6% and 30.9%, respectively. Younger patients had higher rates of regression (p < 0.001) and complete remission (< 0.001) and lower rates of progression (p = 0.003). Among women aged < 25, 25 < 30, 30 < 35, 35 < 40 years, and > 40 years, regression rates were 44.7%, 33.7%, 30.9%, 27.3%, and 24.9%, respectively. Pooled analysis of published data showed similar results. Multivariable analysis showed that with each fve years of age, the odds for regression reduced by 21% (p < 0.001) independently of CIN grade (p < 0.001), and presence of HPV high-risk infection (p < 0.001). Patient’s age has a considerable infuence on the natural history of CIN – independent of CIN grade and HPV high- risk infection.