Ethnographic Studies on Ukrainian Canadian Weddings*

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Black Tie by Ar Gurney

Black Tie.qxd 5/16/2011 2:36 PM Page i BLACK TIE BY A.R. GURNEY ★ ★ DRAMATISTS PLAY SERVICE INC. Black Tie.qxd 5/16/2011 2:36 PM Page 2 BLACK TIE Copyright © 2011, A.R. Gurney All Rights Reserved CAUTION: Professionals and amateurs are hereby warned that performance of BLACK TIE is subject to payment of a royalty. It is fully protected under the copy- right laws of the United States of America, and of all countries covered by the International Copyright Union (including the Dominion of Canada and the rest of the British Commonwealth), and of all countries covered by the Pan-American Copyright Convention, the Universal Copyright Convention, the Berne Convention, and of all countries with which the United States has reciprocal copy- right relations. All rights, including without limitation professional/amateur stage rights, motion picture, recitation, lecturing, public reading, radio broadcasting, tel- evision, video or sound recording, all other forms of mechanical, electronic and digital reproduction, transmission and distribution, such as CD, DVD, the Internet, private and file-sharing networks, information storage and retrieval sys- tems, photocopying, and the rights of translation into foreign languages are strict- ly reserved. Particular emphasis is placed upon the matter of readings, permission for which must be secured from the Author’s agent in writing. The English language stock and amateur stage performance rights in the United States, its territories, possessions and Canada for BLACK TIE are controlled exclusively by DRAMATISTS PLAY SERVICE, INC., 440 Park Avenue South, New York, NY 10016. No professional or nonprofessional performance of the Play may be given without obtaining in advance the written permission of DRAMATISTS PLAY SERVICE, INC., and paying the requisite fee. -

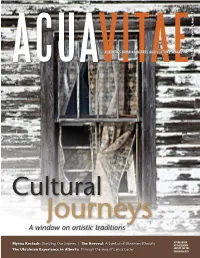

A Window on Artistic Traditions

umber 1 N ummer 2011 | Volume 18, Volume ummer 2011 | ALBERTA’S UKRAINIAN ARTS AND CULTURE MAGAZINE S pring/ S A window on artistic traditions A PUBLICATION Myrna Kostash: Diarizing Our Journey | The Korovai: A Symbol of Ukrainian Ethnicity OF THE ALBERTA The Ukrainian Experience in Alberta: Through the eyes of Larysa Luciw COUNCIL FOR THE UKRAINIAN ARTS ACUAVITAE Spring/Summer 2011 7 16 18 26 features Diarizing Picture This The Art of 8 Our 12 18 the Korovai departments In her stunning Journey photo essay, Anna Chudyk 4 From the Editor Lida Somchynsky Larysa Luciw looks into the speaks to Myrna illustrates The korovai…a symbol 5 Arts & Culture News Kostash about the Ukrainian of Ukrainian true spirit of her Experience in ethnicity. 7 Profile: Tanya in Wonderland work. Alberta. 11 Profile: Carving A Tradition 16 Profile: Ukrainian Youth Orchestras 22 Music: An Interview with Theresa Sokyrka 25 Literary Works: A Short Reminiscence for Babunia 11 Stocky 26 Lystivky: Men of the Bandura on the cover “Window” Photograph by Larysa Luciw Spring/Summer 2011 ACUAVITAE 3 FROM THE EDITOR “The life of an artist is a continuous journey, the path long and never ending” Justin Beckett the 120th anniversary of the first Ukrainian Settlement to Canada-a significant journey that laid the foundation of our community today. In this issue of ACUA Vitae, we explore the cultural journeys of artists from our Ukrainian community. Larysa Luciw gets behind the lens and captures images of the Ukrainian experience ALBERTA’S UKRAINIAN ARTS AND CULTURE MAGAZINE in Alberta; Mary Oakwell takes a look at woodworking; Anna Chudyk Spring/Summer 2011 | Volume 18 Number 1 explores the art and symbol of korovai; and Lida Somchinsky shares with us Publisher: ACUA, The Alberta Myrna Kostash’s literary journey. -

Country Area Studies--Ukraine

Unit 4: Country Area Studies--Ukraine Unit 4: Country Area Studies--Ukraine Objectives At the end of this unit you will Be aware of the following · Ukraine is roughly the size of Texas or Nebraska, Missouri and Arkansas. · Variety of Orthodox Churches in Ukraine · 1993 amendment restricting non-native religious organizations in Ukraine (Non-native Religious Exclusion Amendment) · Bitter disputes between church groups over church properties in Ukraine · Russian language tensions exist--favoring Russian over Ukrainian--exist in Eastern Ukraine and Crimea · Tartar history in the Crimean region · Lack of support systems for victims of domestic violence · Difficulties combating spouse abuse in Ukraine · Extent of U.S. economic assistance to Ukraine · Marriage and death customs Identify · Freedom Support Act, START · Dormition, Theotokos · PfP, USIA, JCTP · Mumming · Chernobyl · SPP · Kupalo Festival · G-7, IMET, Babi Yar 59 Unit 4: Country Area Studies--Ukraine Realize · Though anti-Semitism exists in Ukraine on an individual basis, cultural and constitutional pressures, guaranteeing Jewish religion and cultural activity, officially exist in law and practice. · Difficulty surrounding historic Jewish cemeteries in Ukraine · U.S. policy objectives toward Ukraine · Continued environmental damage due to Chernobyl nuclear reactor explosion · Extent of U.S./Ukraine Defense relationships 60 Unit 4: Country Area Studies--Ukraine Ukraine (yoo-KRAYN) Population 50,864,009 % under 15 years 20% Communication TV 1:3 Radio 1:1.2 Phone 1:6 Newspaper 118:1000 Health Life Expectancy 62 male/72 female Hospital beds 1:81 Doctors 1:224 IMR 22.5:1000 Income $3,370 per capita Literacy Rate 98% 61 Unit 4: Country Area Studies--Ukraine I. -

The Bride Wore White

THE BRIDE WORE WHITE 200 YEARS OF BRIDAL FASHION AT MIEGUNYAH HOUSE MUSEUM CATRIONA FISK THE BRIDE WORE WHITE: 200 YEARS OF WEDDING FASHION AT MIEGUNYAH HOUSE MUSEUM Catriona Fisk Foreword by Jenny Steadman Photography by Beth Lismanis and Julie Martin Proudly Supported by a Brisbane City Council Community History Grant Dedicated to a better Brisbane QUEENSLAND WOMen’s HISTORICAL ASSOCIATION, 2013 © ISBN: 978-0-9578228-6-3 INDEX Index 3 Foreword 5 Introduction 6 Wedding Dresses & Outfits 9 Veils, Headpieces & Accessories 29 Shoes 47 Portraits, Photographs & Paper Materials 53 List of Donors 63 Photo Credits 66 Notes 67 THE BRIDE WORE WHITE AcKNOWLEDGEMENTS Thanks are extended to Jenny Steadman for her vision and Helen Cameron and Julie Martin for their help and support during the process of preparing this catalogue. The advice of Dr Michael Marendy is also greatly appreciated. I also wish to express gratitude to Brisbane City Council for the opportunity and funding that allowed this project to be realised. Finally Sandra Hyde-Page and the members of the QWHA, for their limitless dedication and care which is the foundation on which this whole project is built. PAGE 4 FOREWORD FOREWORD The world of the social history museum is a microcosm of the society from which it has arisen. It reflects the educational and social standards of historic and contemporary life and will change its focus as it is influenced by cultural change. Today it is no longer acceptable for a museum to simply exist. As Stephen Weil said in 2002, museums have to shift focus “from function to purpose” and demonstrate relevance to the local community. -

The Ukrainian Weekly 2008, No.39

www.ukrweekly.com INSIDE: • Askold Lozynskyj reflects on two terms leading UWC – page 3. • New film about Metropolitan Andrey Sheptytsky – page 9. • What’s a wedding without a “korovai”? – page 13 HE KRAINIAN EEKLY T PublishedU by the Ukrainian National Association Inc., a fraternal Wnon-profit association Vol. LXXVI No. 39 THE UKRAINIAN WEEKLY SUNDAY, SEPTEMBER 28, 2008 $1/$2 in Ukraine UNA General Assembly Yushchenko least trusted politician meets at annual session in Ukraine, according to new poll by Roma Hadzewycz Groch, National Secretary Christine Kozak and Treasurer Roma Lisovich; Auditors KERHONKSON, N.Y. – Members of Slavko Tysiak and Wasyl Szeremeta; the Ukrainian National Association’s Advisors Maya Lew, Gloria Horbaty, General Assembly gathered at their annual Eugene Oscislawski, Olya Czerkas, Eugene meeting on September 12-14 were buoyed Serba and Lubov Streletsky; Honorary by the news of a rebound in the UNA’s Member Myron B. Kuropas; as well as the insurance business, thanks largely to over editor-in-chief of The Ukrainian Weekly $6 million in annuity sales during the first and Svoboda, Roma Hadzewycz. half of 2008, plus an overall increase in the The proceedings were opened, in accor- sales of life insurance policies during the dance with longstanding UNA tradition, past year. with the singing of the national anthems of Other topics discussed at the annual the United States, Canada and Ukraine, as meeting were developments at the well as Taras Shevchenko’s “Zapovit” Soyuzivka Heritage Center, the future of (Testament). Due to rain, the ceremony was UNA activity in Canada, fraternal programs held indoors, not at Soyuzivka’s monument and organizing efforts, and marketing and to Shevchenko, whom the UNA honors as advertising of the UNA’s two newspapers, its patron. -

Selling Daughters: Age of Marriage, Income Shocks and the Bride Price Tradition

Selling daughters: age of marriage, income shocks and the bride price tradition IFS Working Paper W16/08 Lucia Corno Alessandra Voena The Institute for Fiscal Studies (IFS) is an independent research institute whose remit is to carry out rigorous economic research into public policy and to disseminate the findings of this research. IFS receives generous support from the Economic and Social Research Council, in particular via the ESRC Centre for the Microeconomic Analysis of Public Policy (CPP). The content of our working papers is the work of their authors and does not necessarily represent the views of IFS research staff or affiliates. Selling daughters: age of marriage, income shocks and the bride price tradition⇤ Lucia Corno† Alessandra Voena ‡ June 11, 2016 Abstract When markets are incomplete, cultural norms may play an important role in shap- ing economic behavior. In this paper, we explore whether income shocks increase the probability of child marriages in societies that engage in bride price payments – transfers from the groom to the bride’s parents at marriage. We develop a simple model in which households are exposed to income volatility and have no access to credit markets. If a daughter marries, the household obtains a bride price and has fewer members to support. In this framework, girls have a higher probability of marrying early when their parents have higher marginal utility of consumption because of adverse income shocks. We test the prediction of the model by exploiting variation in rainfall shocks over a woman’s life cycle, using a survey dataset from rural Tanzania. We find that adverse shocks during teenage years increase the probability of early marriages and early fertility among women. -

Instructor's Guide

As Long as We Both Shall Love The White Wedding in Postwar America INSTRUCTOR’S GUIDE As Long As We Both Shall Love explains why the American wedding has retained its cultural power, despite the many social, political, and economic changes of decades following World War II. The modern white wedding – an event marked by engagement with the marketplace, recognition of prescribed gender roles and re- sponsibilities, declaration of religious or spiri- tual belonging, and self-conscious embrace of “traditions” such as formal dress, proper vows, and a post-ceremony reception – has survived, and even thrived, Karen Dunak argues, be- cause of couples’ ability to personalize the celebration and exert individual authority over its shape. The wedding’s ability to withstand and even absorb challenges or interpretation has helped the celebration maintain its long-standing ap- peal. Because accepted wedding traditions, such as an exchange of vows before a select- ed authority fi gure, the witness of the celebra- tion by a chosen audience, or the hosting of a post-wedding reception, could be shaped to fi t personal values and visions, celebrants – from sweethearts of the early postwar years to hippies of the 1960s to same-sex couples of the 2000s – maintained those traditions. While couples had long aimed to make their wedding distinctive, as the twentieth century came to a close and the twenty-fi rst century began, adding a unique element to a wedding became an increasingly standard practice. The fact that weddings allowed for experimenta- tion opened doors for both how and by whom weddings might be celebrated. -

Dear Bride and Groom to Be, Congratulations on Your Recent

Dear Bride and Groom to be, Congratulations on your recent engagement! We appreciate the opportunity to be part of your special day. Because the leadership at River Point Community Church believes marriage is an institution established by God and a lifetime commitment, we have enclosed a copy of our Wedding Policies and Procedures in the packet. We would like for you and your fiancé to carefully read the enclosed material. If you desire to move forward with your wedding here at River Point Community Church, please complete the Wedding Request Form and return it to Gwen Wetherton in the church office or via email ([email protected]) as soon as possible. If you have any questions, please call the church office at (706)778-5000 In His Service, River Point Community Church Leadership A Word to the Bride and Groom As you approach the day when you make a total life commitment to each other, you, the bride and groom, are entering a time in your life marked by excited preparation and joyful expectations. Your wedding day is a day to be remembered with gratitude to God for His grace and goodness in making the union possible. Marriage is a union ordained by God. It was first instituted by God in the early chapters of Genesis 1 and 2. The Old Testament prophets compared it to a relationship between God and his people. Jesus Christ explained the original intention and core elements of marriage, and several New Testament Epistles give explicit instructions on this union. As such, the church views marriage as a profound spiritual institution established by God. -

CONGRATULATIONS Perks of Being a Charlotte's Bride

CONGRATULATIONS Perks Of Being A Charlotte's Bride Private Facebook Group Invites to Private Events Educational Seminars Special Promotions Featured Bride Opportunities Bridal Party Exclusive Offers Entry Fee Promos to Bridal Shows Special Pricing on Steam & Press and Gown Preservation Cut 5.85” from the top LET'S GET SOCIAL ow that you have purchased your gown, it's time to let your friends and family know that you are a NCharlotte's Bride!! WHERE CAN YOU FIND US AND HOW DO YOU SHARE? Join our Charlotte's Facebook Page CharlottesBridePDX Tag us in your Say Yes to the Dress pics and give a SHOUT OUT to your Stylist Refer your newly engaged friends and family to Charlotte's Post and Tag us in your wedding gown photos to be a featured bride on our website Let other brides know how amazing your experience was at Charlotte's so they can see how magical it can be! HELP FUTURE BRIDES SAY YES TO THE DRESS AT CHARLOTTE'S BY LEAVING US A 5 STAR REVIEW ON THE FOLLOWING SITES: THE KNOT GOOGLE FACEBOOK WEDDINGWIRE Cut 6.87” from the top BRIDAL ATTIRE CHEckLIST AND TIMELINE EIGHT TO TWELVE ONE TO TWO MONTHS BEFORE WEDDING MONTHS BEFORE WEDDING Find and order your perfect gown Have wedding gown and bridesmaid gowns altered Start to look at bridesmaid gowns and Set up an appointment with Charlotte’s to have mother of the bride gowns gowns pressed Finalize men’s formal wear – Tuxedo rentals FOUR TO FIVE MONTHS BEFORE WEDDING WEEK BEFORE WEDDING Order bridesmaid gowns Drop gowns off for pressing at Charlotte's Order mother of the bride and mother of the -

Planning Your Wedding As a Catholic Bride and Catholic Groom

Planning Your Wedding as a Catholic Bride and Catholic Groom As you make your plans for marriage, keep in mind that noble simplicity should be the order of the day. A service with the Eucharist (Mass) should run approximately one hour. Your guests will appreciate the brevity and the sacredness of the event. There are five basic parts to a wedding: The Procession, the Liturgy of the Word, The Exchange of Vows, the Mass (if acceptable), and the Recessional. Catholic Wedding With a Mass If you are both Catholic and wish to participate in the Eucharistic liturgy (the Mass), follow these simple guidelines. If one of you is not Catholic, but the Catholic party would still like a Mass, make sure that you have discussed this with the person performing your marriage before you proceed: Procession There are a number of ways to begin your wedding service with a procession down the aisle. There isn't one traditional way. The basic rule of thumb is, "Getting down the aisle is far more important than how you get down the aisle." The most common traditions for getting down the aisle are as follows: 1. Seating of the Mother of the Groom Seating of the Mother of the Bride (Lighting of the Taper Candles: This is used when a Unity Candle ceremony is included in the service. Often, the mothers of the bride and groom light the taper candles prior to being seated. However, this may also be done just before the Unity Candle ceremony). Procession of Wedding Entourage (ushers & bridesmaids) Procession of the Bride with her Father or Parent (as the Groom stands at the sanctuary) 2. -

Our Wedding Dress Appointment Guide Ongratulations! You’Re Getting Married

Our Wedding Dress Appointment Guide ongratulations! You’re getting married. The weeks and months leading up to the wedding will be filled with joy and most likely, Finding the perfect some stress as you plan for your big day, choosing everything from Instagram-able dress for your appetizers to a gorgeous get-away car. For many brides, though, there is no decision more important than finding the right dress for perfect day her wedding. Wherever your aisle might be, everyone will be standing to see you radiant in that gown. Wedding Dress Shopping P laylist At The White Dress, we’ve seen every kind of wedding and we have a dress for each one. But we know that sorting through all the available options can be overwhelming. That’s why we’ve created this “All You Need Is Love” “Almost Like Being in Love” by The Beatles by Nat King Cole guide. We’ll talk about the kinds of things that go into having a great dress shopping experience, from having a budget to deciding who to bring. We’ll also walk you through some popular styles and flattering “At Last” “I Say a Little Prayer” by Etta James by Aretha Franklin fits and teach you the two rules of wedding dress selection. If you read this guide carefully, by the time you book “I Do” “Ain’t No Mountain High Enough” by Colbie Caillat by Marvin Gaye and Tammi Terrell your first appointment, your time at the boutique should be peaceful and uncomplicated. As every bride knows, finding the right dress isn’t just about ticking off a checklist. -

First Class Mail PAID

FOLK DANCE SCENE First Class Mail 4362 COOLIDGE AVE. U.S. POSTAGE LOS ANGELES, CA 90066 PAID Inglewood, CA Permit No. 134 First Class Mail Dated Material ORDER FORM Please enter my subscription to FOLK DANCE SCENE for one year, beginning with the next published issue. Subscription rate: $15.00/year U.S.A., $20.00/year Canada or Mexico, $25.00/year other countries. Published monthly except for June/July and December/January issues. NAME _________________________________________ ADDRESS _________________________________________ PHONE (_____)_____–________ CITY _________________________________________ STATE __________________ E-MAIL _________________________________________ ZIP __________–________ Please mail subscription orders to the Subscription Office: 2010 Parnell Avenue Los Angeles, CA 90025 (Allow 6-8 weeks for subscription to go into effect if order is mailed after the 10th of the month.) Published by the Folk Dance Federation of California, South Volume 40, No. 10 Dec. 2004/Jan. 2005 Folk Dance Scene Committee Club Directory Coordinators Jay Michtom [email protected] (818) 368-1957 Jill Michtom [email protected] (818) 368-1957 Calendar Jay Michtom [email protected] (818) 368-1957 Beginner’s Classes (cont.) On the Scene Jill Michtom [email protected] (818) 368-1957 Club Directory Steve Himel [email protected] (949) 646-7082 Club Time Contact Location Contributing Editor Richard Duree [email protected] (714) 641-7450 CONEJO VALLEY FOLK Wed 7:30 (805) 497-1957 THOUSAND OAKS, Hillcrest Center, Contributing Editor Jatila van der Veen [email protected] (805) 964-5591 DANCERS Jill Lungren 403 W Hillcrest Dr Proofreading Editor Laurette Carlson [email protected] (310) 397-2450 ETHNIC EXPRESS INT'L Wed 6:30-7:15 (702) 732-4871 LAS VEGAS, Charleston Heights Art FOLK DANCERS except holidays Richard Killian Center, 800 S.