Garfield on Sheehy and Mathes, 'The Other Emptiness: Rethinking the Zhentong Buddhist Discourse in Tibet'

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

VT Module6 Lineage Text Major Schools of Tibetan Buddhism

THE MAJOR SCHOOLS OF TIBETAN BUDDHISM By Pema Khandro A BIRD’S EYE VIEW 1. NYINGMA LINEAGE a. Pema Khandro’s lineage. Literally means: ancient school or old school. Nyingmapas rely on the old tantras or the original interpretation of Tantra as it was given from Padmasambhava. b. Founded in 8th century by Padmasambhava, an Indian Yogi who synthesized the teachings of the Indian MahaSiddhas, the Buddhist Tantras, and Dzogchen. He gave this teaching (known as Vajrayana) in Tibet. c. Systemizes Buddhist philosophy and practice into 9 Yanas. The Inner Tantras (what Pema Khandro Rinpoche teaches primarily) are the last three. d. It is not a centralized hierarchy like the Sarma (new translation schools), which have a figure head similar to the Pope. Instead, the Nyingma tradition is de-centralized, with every Lama is the head of their own sangha. There are many different lineages within the Nyingma. e. A major characteristic of the Nyingma tradition is the emphasis in the Tibetan Yogi tradition – the Ngakpa tradition. However, once the Sarma translations set the tone for monasticism in Tibet, the Nyingmas also developed a monastic and institutionalized segment of the tradition. But many Nyingmas are Ngakpas or non-monastic practitioners. f. A major characteristic of the Nyingma tradition is that it is characterized by treasure revelations (gterma). These are visionary revelations of updated communications of the Vajrayana teachings. Ultimately treasure revelations are the same dharma principles but spoken in new ways, at new times and new places to new people. Because of these each treasure tradition is unique, this is the major reason behind the diversity within the Nyingma. -

Brief History of Dzogchen

Brief History of Dzogchen This is the printer-friendly version of: http: / / www.berzinarchives.com / web / en / archives / advanced / dzogchen / basic_points / brief_history_dzogchen.html Alexander Berzin November 10-12, 2000 Introduction Dzogchen (rdzogs-chen), the great completeness, is a Mahayana system of practice leading to enlightenment and involves a view of reality, way of meditating, and way of behaving (lta-sgom-spyod gsum). It is found earliest in the Nyingma and Bon (pre-Buddhist) traditions. Bon, according to its own description, was founded in Tazig (sTag-gzig), an Iranian cultural area of Central Asia, by Shenrab Miwo (gShen-rab mi-bo) and was brought to Zhang-zhung (Western Tibet) in the eleventh century BCE. There is no way to validate this scientifically. Buddha lived in the sixth century BCE in India. The Introduction of Pre-Nyingma Buddhism and Zhang-zhung Rites to Central Tibet Zhang-zhung was conquered by Yarlung (Central Tibet) in 645 CE. The Yarlung Emperor Songtsen-gampo (Srong-btsan sgam-po) had wives not only from the Chinese and Nepali royal families (both of whom brought a few Buddhist texts and statues), but also from the royal family of Zhang-zhung. The court adopted Zhang-zhung (Bon) burial rituals and animal sacrifice, although Bon says that animal sacrifice was native to Tibet, not a Bon custom. The Emperor built thirteen Buddhist temples around Tibet and Bhutan, but did not found any monasteries. This pre-Nyingma phase of Buddhism in Central Tibet did not have dzogchen teachings. In fact, it is difficult to ascertain what level of Buddhist teachings and practice were introduced. -

Learn Tibetan & Study Buddhism

fpmt Mandala BLISSFUL RAYS OF THE MANDALA IN THE SERVICE OF OTHERS JULY - SEPTEMBER 2012 TEACHING A GOOD HEART: FPMT REGISTERED TEACHERS THE OFFICIAL PUBLICATION OF THE FOUNDATION FOR THE PRESERVATION OF THE MAHAYANA TRADITION Wisdom Publications Delve into the heart of emptiness. INSIGHT INTO EMPTINESS Khensur Jampa Tegchok Edited by Thubten Chodron A former abbot of Sera Monastic University, Khensur Jampa Tegchok here unpacks with great erudi- tion Buddhism’s animating philosophical principle—the emptiness of all appearances. “Khensur Rinpoche Jampa Tegchok is renowned for his keen understanding of philosophy, and of Madhyamaka in particular. Here you will find vital points and reasoning for a clear understanding of emptiness.”—Lama Zopa Rinpoche, author of How to Be Happy 9781614290131 “This is one of the best introductions to the philosophy of emptiness 336 pages | $18.95 I have ever read.”—José Ignacio Cabezón, Dalai Lama Professor and eBook 9781614290223 Chair, Religious Studies Department, UC Santa Barbara Wisdom Essentials JOURNEY TO CERTAINTY The Quintessence of the Dzogchen View: An Exploration of Mipham’s Beacon of Certainty Anyen Rinpoche Translated and edited by Allison Choying Zangmo Approachable yet sophisticated, this book takes the reader on a gently guided tour of one of the most important texts Tibetan Buddhism has to offer. “Anyen Rinpoche flawlessly presents the reader with the unique perspective that belongs to a true scholar-yogi. A must-read for philosophers and practitioners.” —Erik Pema Kunsang, author of Wellsprings of the Great Perfection and 9781614290094 248 pages | $17.95 compiler of Blazing Splendor eBook 9781614290179 ESSENTIAL MIND TRAINING Thupten Jinpa “The clarity and raw power of these thousand-year-old teachings of the great Kadampa masters are astonishingly fresh.”—Buddhadharma “This volume can break new ground in bridging the ancient wisdom of Buddhism with the cutting-edge positive psychology of happiness.” —B. -

The Dzogchen Path ~

~ The Dzogchen Path ~ Mingyur Rinpoche Dzogchen is called "Ati yoga" in Sanskrit and the “Great Perfection" in English. The Nine yanas encompass the complete practices of all of Buddhism. Including the Dzogchen tradition, practices are categorized into nine yanas that give a complete picture of the entire buddhadharma. Within the nine yanas, the highest one is Ati. The way that Ati yoga is structured, most of the teachings are categorized as the ground, path, and fruition. These are the three categories. The ground means the “principle” because the main focus of Dzogchen is the view. The view is the perspective or the principle, which is very important in Dzogchen. Before meditation, we have what we call "the ground." “The ground” means “who we are, who you are, who I am.” The fundamental nature of all of us is explained in the ground. I will teach you about the ground aspect of Dzogchen later. Now, I would like to focus on the Dzogchen path. In Dzogchen, normally there is not too much shamatha meditation. In Mahamudra, we have this step-by-step shamatha meditation practice. First, we look at how our minds relate to meditation and how we can free our minds. Next, experience comes, and then the next level of meditation. That is the Mahamudra style. In Dzogchen, there is not so much of this step-by-step shamatha practice. The main teaching of Dzogchen is what we call "trekchö," meaning "cutting through." In the teachings of trekchö, the first important thing is pointing out the nature of mind. Of course, we need to have a foundational practice before that. -

2011, Volume 20, Number 1

Winter 2011 Volume 20, Number 1 Sakyadhita International Association of Buddhist Women TABLE OF CONTENTS Sharing Impressions, Meeting Expectations: Evaluating the 12th Sakyadhita Conference Titi Soentoro The Question of Lineage in Tibetan Buddhism: A Woman’s Perspective Jetsunma Tenzin Palmo Lipstick Buddhists and Dharma Divas: Buddhism in the Most Unlikely Packages Lisa J. Battaglia The Anti-Virus Enlightenment Hyunmi Cho Risks and Opportunities of Scholarly Engagement with Buddhism Christine Murphy SHARING IMPRESSIONS, MEETING EXPECTATIONS Evaluating the 12th Sakyadhita Conference Grace Schireson in Interview By Titi Soentoro Janice Tolman Full Ordination for Women and It was a great joy to be among such esteemed scholars, nuns, and laywomen at the 12th Sakyadhita the Fourfold Sangha International Conference on Buddhist Women held in Bangkok from June 12 to 18, 2011. It felt like such Santacitta Bhikkhuni an honor just to be in their company. This feeling was shared by all the participants. Around the general A SeeSaw theme, “Leading to Liberation, the conference addressed many issues of Buddhist women, including Wendy Lin issues that people don’t generally associate with Buddhist women, such as the environment and LGBTQ concerns. Sakyadhita in Cyberspace: Sakyadhita and the Social Media At the end of the conference, participants were asked to share their feelings and insights, and to Revolution offer suggestions for the next Sakyadhita Conference. The evaluations asked which aspects they enjoyed Charlotte B. Collins the most and the least, which panels and workshops they learned the most from, and for suggestions for themes and topics for the next Sakyadhita Conference in India. In many languages, participants shared A Tragic Episode Rebecca Paxton their reflections on all aspects of the conference Further Reading What Participants Appreciated Most Overall, respondents found the conference very interesting and enjoyable. -

Biographies of Dzogchen Masters ~

~ Biographies of Dzogchen Masters ~ Jigme Lingpa: A Guide to His Works It is hard to overstate the importance of Jigme Lingpa to the Nyingma tradition of Tibetan Buddhism. This itinerant yogi, along with Rongzom Mahapandita, Longchenpa, and-later-Mipham Rinpoche, are like four pillars of the tradition. He is considered the incarnation of both the great master Vimalamitra and the Dharma king Trisong Detsen. After becoming a monk, he had a vision of Mañjuśrīmitra which caused him to change his monks robes for the white shawl and long hair of a yogi. In his late twenties, he began a long retreat during which he experienced visions and discovered termas. A subsequent retreat a few years later was the container for multiple visions of Longchenpa, the result of which was the Longchen Nyingthig tradition of terma texts, sadhanas, prayers, and instructions. What many consider the best source for understanding Jigme Lingpa's relevance, and his milieu is Tulku Thondup Rinpoche's Masters of Meditation and Miracles: Lives of the Great Buddhist Masters of India and Tibet. While the biographical coverage of him only comprises about 18 pages, this work provides the clearest scope of the overall world of Jigme Lingpa, his line of incarnations, and the tradition and branches of teachings that stem from him. Here is Tulku Thondup Rinpoche's account of his revelation of the Longchen Nyingtik. "At twenty-eight, he discovered the extraordinary revelation of the Longchen Nyingthig cycle, the teachings of the Dharmakāya and Guru Rinpoche, as mind ter. In the evening of the twenty-fifth day of the tenth month of the Fire Ox year of the thirteenth Rabjung cycle (1757), he went to bed with an unbearable devotion to Guru Rinpoche in his heart; a stream of tears of sadness continuously wet his face because he was not 1 in Guru Rinpoche's presence, and unceasing words of prayers kept singing in his breath. -

Lineage Position and Transmission in the Namthar of Do Dasel Wangmo Ravenna Necara Michalsen University of Colorado at Boulder, [email protected]

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by CU Scholar Institutional Repository University of Colorado, Boulder CU Scholar Religious Studies Graduate Theses & Dissertations Religious Studies Spring 1-1-2012 Daughter of Self-Liberation: Lineage Position and Transmission in the Namthar of Do Dasel Wangmo Ravenna Necara Michalsen University of Colorado at Boulder, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://scholar.colorado.edu/rlst_gradetds Part of the Buddhist Studies Commons, and the Feminist, Gender, and Sexuality Studies Commons Recommended Citation Michalsen, Ravenna Necara, "Daughter of Self-Liberation: Lineage Position and Transmission in the Namthar of Do Dasel Wangmo" (2012). Religious Studies Graduate Theses & Dissertations. Paper 12. This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Religious Studies at CU Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Religious Studies Graduate Theses & Dissertations by an authorized administrator of CU Scholar. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Daughter of Self-Liberation: Lineage Position and Transmission in the Namthar of Do Dasel Wangmo by Ravenna Necara Michalsen B.A., M.A. Yale University 2001, 2004 A thesis submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Colorado in partial fulfillment Of the requirement for the degree of Masters of Arts Department of Religious Studies 2012 This thesis entitled: Daughter of Self-Liberation: Lineage Position and Transmission in the Namthar of Do Dasel Wangmo written by Ravenna Necara Michalsen Has been approved for the Department of Religious Studies Dr. Holly Gayley Dr. Gregory Johnson Date: ________________ The final copy of this thesis has been examined by the signatories, and we find that both the content and the form meet acceptable presentation standards of scholarly work in the above- mentioned discipline. -

Supplication to the Takpo Kagyu Great Vajradhara, Tilo, Naro, Marpa, Mila

Supplication to the Takpo Kagyu Great Vajradhara, Tilo, Naro, Marpa, Mila, Lord of Dharma Gampopa, Knower of the Three Times, omniscient Karmapa, Holders of the four great and eight lesser lineages— Drikung, Tag-lung, Tsalpa, these three, glorious Drukpa and so on— Masters of the profound path of mahamudra, Incomparable protectors of beings, the Takpo Kagyu, I supplicate you, the Kagyü gurus. I hold your lineage; grant your blessings so that I will follow your example. Revulsion is the foot of meditation, as is taught. To this meditator who is not attached to food and wealth, Who cuts the ties to this life, Grant your blessings so that I have no desire for honor and gain. Devotion is the head of meditation, as is taught. The guru opens the gate to the treasury of oral instructions. To this meditator who continually supplicates him Grant your blessings so that genuine devotion is born in me. Awareness is the body of meditation, as it taught. Whatever arises is fresh—the essence of realization. To this meditator who rests simply without altering it Grant your blessings so that my meditation is free from conception. The essence of thoughts is dharmakaya, as is taught. Nothing whatever but everything arises from it. To this meditator who arises in unceasing play Grant your blessings so that I realize the inseparability of samsara and nirvana. Through all my births may I not be separated from the perfect guru And so enjoy the splendor of dharma. Perfecting the virtues of the paths and bhumis, May I speedily attain the state of Vajradhara. -

The Life and Vicissitudes of Khandro Choechen Nicola Schneider

Self-Representation and Stories Told: the Life and Vicissitudes of Khandro Choechen Nicola Schneider To cite this version: Nicola Schneider. Self-Representation and Stories Told: the Life and Vicissitudes of Khandro Choechen. Revue d’Etudes Tibétaines, CNRS, 2015. hal-03210266 HAL Id: hal-03210266 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-03210266 Submitted on 27 Apr 2021 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Self-Representation and Stories Told: the Life and Vicissitudes of Khandro Choechen Nicola Schneider (Centre de Recherche sur les Civilisations d’Asie Orientale)1 n Tibetan Buddhism, the female figure of the khandroma (mkha’ ’gro ma) is an elusive one, especially in her divine I form,2 but also when applied to a particular woman. Most often, khandroma refers to a lama’s wife (or his consort)—who is usually addressed by this title—, but there are also other female religious specialists known as such. Some are nuns, like the famous Mumtsho (Mu mtsho, short for Mu med ye shes mtsho mo, b. 1966) from Serthar,3 yet others are neither nuns nor consorts. All can be considered, in varying degrees, as holy women or female saints. -

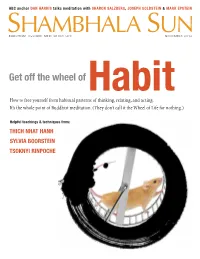

Tsoknyi Rinpoche E Whee Th L O F F F H O A

ABC anchor DAN HARRIS talks meditation with SHARON SALZBERG, JOSEPH GOLDSTEIN & MARK EPSTEIN SBUDDHISMHAMBHALA CULTURE MEDITATION LIFE SUNNOVEMBER 2014 Get off the wheel of How to free yourself from habitual patternsHabit of thinking, relating, and acting. It’s the whole point of Buddhist meditation. (They don’t call it the Wheel of Life for nothing.) Helpful teachings & techniques from: THICH NHAT HANH SYLVIA BOORSTEIN TSOKNYI RINPOCHE e Whee th l o f f f H O a t b e i t G The Natural Liberation of Habits When you recognize the true nature of mind, says Dzogchen master TSOKNYI RINPOCHE, all habitual patterns are naturally liberated in the space of wisdom. That includes the ultimate habit known as samsara. HE ULTIMATE HABITUAL PATTERN is samsara itself—the wheel of habitual cyclic existence that causes all your suffering. The karma that drives the wheel— the three poisons of attachment, aggression, and ignorance—are actually deep- seated habits of mind. TWhen you finally get tired of unconsciously participating in the daily show of habitual samsaric programming, what can you do to change it? Buddhism teaches three basic ways to cut your ties to samsara, once you have decided this is something you really need and want to do. One approach is to shut off the world of phenomena and your attachment to it. This is the path of renunciation. It is illustrated by the paintings of skeletons on the walls of temples in Burma or Thailand. They are reminders to Theravada monks and nuns to stay free of desire and attachment arising in their mind. -

Introduction to Dzogchen

WISDOM ACADEMY Introduction to Dzogchen B. ALAN WALLACE Lesson 1: Introduction to Düdjom Lingpa and the Text Reading: Heart of the Great Perfection: Düdjom Lingpa’s Visions of the Great Perfection, Vol. 1 Introduction, pages 1–21 Wisdom Publications, Inc.—Not for Distribution Heart of the Great Perfection --9-- düdjom lingpa’s visions of the great perfection, volume 1 Foreword by Sogyal Rinpoche Translated by B. Alan Wallace Edited by Dion Blundell Wisdom Publications, Inc.—Not for Distribution Wisdom Publications 199 Elm Street Somerville, MA 02144 USA wisdompubs.org © 2016 B. Alan Wallace Foreword © 2016 Tertön Sogyal Trust All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photography, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system or technologies now known or later developed, without permission in writing from the publisher. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Bdud-’joms-glin-pa, Gter-ston, 1835–1904. [Works. Selections. English] Düdjom Lingpa’s visions of the Great Perfection / Translated by B. Alan Wallace ; Edited by Dion Blundell. volumes cm Includes bibliographical references and index. Contents: Volume 1. Heart of the Great Perfection — volume 2. Buddhahood without meditation — volume 3. TheV ajra essence. ISBN 1-61429-260-4 (pbk. : alk. paper) 1. Rdzogs-chen. I. Wallace, B. Alan. II. Title. BQ942.D777A25 2016 294.3’420423—dc23 2014048350 ISBN 978-1-61429-348-4 ebook ISBN 978-1-61429-236-4 First paperback edition 20 19 18 17 16 5 4 3 2 1 Cover and interior design by Gopa & Ted2, Inc. -

Dzogchen Terms

Dzogchen Terms A The white Tibetan letter A is the symbol of Shunyata and of primordial wisdom. Attitude Awareness, Non-judging, Patience, Relaxed Mind, Integration, Presence, Non-striving, Acceptance, Nonduality, Letting Go, Beyond Mind. Awareness The awareness (pozornosť) of natural perfection is everywhere, its parameters beyond indication, its actuality incommunicable; the sovereign view of natural perfection is the here-and-now, naturally present without speech or books, irrespective of conceptual clarity or dullness, but as spontaneous joyful creativity its reality is nothing at all. — Natural Perfection, Longchenpa’s Radical Dzogchen Bodhichitta Relative Bodhichitta is a state of being awake, tender, and genuine. The Sanskrit term bodhi means “wakefulness” (bdelosť). The ground of nonthought is Absolute Bodhichitta. Buddha Nature The nature of mind, synonym for ‘buddha nature’ or Dzogchen, or the potentiality of vajra in vajrayana. It should be distinguished from ‘mind’ (sems), which refers to ordinary discursive thinking based on ignorance. ‘Mind Essence’ is the basic space from and within which these thoughts take place. Dharmakaya Naked and aware emptiness. Dzogchen Dzogchen – Great Perfection; the state of contemplation beyond the mind; mental processes not conditioning awareness. Dzogchen is about resting in the “primordial state of pure awareness”. The term also derives from the “highest perfection” of the Vajrayana practice after the visualization of the deity and the mantra recitation is dissolved and one rests in the natural state of luminous and pure awareness. Dzogchen – Tibetan Great Perfection – is also considered as “The Zen of Tantra”. Dzogchen is a sudden path with gradual cultivation. — 1 There exist three series of Dzogchen teachings: the Mind Series (semde), the Space Series (longde), and the Secret Instruction Series (mangagde).