All Worms Have Some Things in Common. All of Them Are Invertebrates. They All Have Long, Narrow Bodies Without Legs. All Worms A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Effect of Invasive Earthworm Lumbricus Terrestris on The

The Effect of Invasive Earthworm Lumbricus terrestris on the Distribution of Nitrogen in Soil Profile Sarah Adelson, Christine Doman, Gillian Golembiewski, Luke Middleton University of Michigan Biological Station, Spring 2009 Abstract The purpose of this study was to determine if Lumbricus terrestris, an invasive earthworm in Northern Michigan, is redistributing nitrogen from the organic soil layer to the deeper, mineral soil layer. L. terrestris burrow 2 meters vertically into the ground and emerge to feed on freshly fallen leaf litter. The study included collecting of L. terrestris in 16 0.5 m square plots by method of electro-shock. Soil cores from a depth of 0-5 and 30-40 cm as well as leaf litter were taken from each plot to determine nitrogen content and nitrogen isotope ratios. Data analysis resulted in no significance between plots with earthworms and without earthworms in both nitrogen, N, isotope ratios and N content. Plots with L. terrestris showed no difference between the organic and mineral soil layer. This result suggests that L. terrestris are homogenizing soil layers. However, smaller than ideal sample sizes limit interpretive capacity of the results. Further research needs to be completed to confirm these perceived trends. The analysis of nitrogen isotope ratios suggest that there is another source of 15N other than leaf litter and L. terrestris that is contributing to soil composition and therefore the contribution of each was not conclusively determined. Introduction Invasion of an exotic species into an ecosystem is one of the leading threats to biologically diverse ecosystems throughout the world. Exotic species are initially introduced as a solution for food, farming, aesthetic purposes, or even accidentally. -

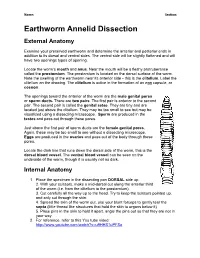

Earthworm Annelid Dissection External Anatomy

Name: Section: Earthworm Annelid Dissection External Anatomy Examine your preserved earthworm and determine the anterior and posterior ends in addition to its dorsal and ventral sides. The ventral side will be slightly flattened and will have two openings types of opening. Locate the worm's mouth and anus. Near the mouth will be a fleshy protruberance called the prostomium. The prostomium is located on the dorsal surface of the worm. Note the swelling of the earthworm near its anterior side - this is the clitellum. Label the clitellum on the drawing. The clitellum is active in the formation of an egg capsule, or cocoon. The openings toward the anterior of the worm are the male genital pores or sperm ducts. There are two pairs. The first pair is anterior to the second pair. The second pair is called the genital setae. They are tiny and are located just above the clitellum. They may be too small to see but may be visualized using a dissecting microscope. Sperm are produced in the testes and pass out through these pores. Just above the first pair of sperm ducts are the female genital pores. Again, these may be too small to see without a dissecting microscope. Eggs are produced in the ovaries and pass out of the body through these pores. Locate the dark line that runs down the dorsal side of the worm, this is the dorsal blood vessel. The ventral blood vessel can be seen on the underside of the worm, though it is usually not as dark. Internal Anatomy 1. Place the specimen in the dissecting pan DORSAL side up. -

Mapping and Distribution of Sabella Spallanzanii in Port Phillip Bay Final

Mapping and distribution of Sabellaspallanzanii in Port Phillip Bay Final Report to Fisheries Research and Development Corporation (FRDC Project 94/164) G..D. Parry, M.M. Lockett, D.P. Crookes, N. Coleman and M.A. Sinclair May 1996 Mapping and distribution of Sabellaspallanzanii in Port Phillip Bay Final Report to Fisheries Research and Development Corporation (FRDC Project 94/164) G.D. Parry1, M. Lockett1, D. P. Crookes1, N. Coleman1 and M. Sinclair2 May 1996 1Victorian Fisheries Research Institute Departmentof Conservation and Natural Resources PO Box 114, Queenscliff,Victoria 3225 2Departmentof Ecology and Evolutionary Biology Monash University Clayton Victoria 3068 Contents Page Technical and non-technical summary 2 Introduction 3 Background 3 Need 4 Objectives 4 Methods 5 Results 5 Benefits 5 Intellectual Property 6 Further Development 6 Staff 6 Final cost 7 Distribution 7 Acknow ledgments 8 References 8 Technical and Non-technical Summary • The sabellid polychaete Sabella spallanzanii, a native to the Mediterranean, established in Port Phillip Bay in the late 1980s. Initially it was found only in Corio Bay, but during the past fiveyears it has spread so that it now occurs throughout the western half of Port Phillip Bay. • Densities of Sabella in many parts of the bay remain low but densities are usually higher (up to 13/m2 ) in deeper water and they extend into shallower depths in calmer regions. • Sabella larvae probably require a 'hard' surface (shell fragment, rock, seaweed, mollusc or sea squirt) for initial attachment, but subsequently they may use their own tube as an anchor in soft sediment . • Changes to fish communities following the establishment of Sabella were analysed using multidimensional scaling and BACI (Before, After, Control, Impact) design analyses of variance. -

Utilizing Soil Characteristics, Tissue Residues, Invertebrate Exposures

Utilizing soil characteristics, tissue residues, invertebrate exposures and invertebrate community analyses to evaluate a lead-contaminated site: A shooting range case study Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy In the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Sarah R. Bowman, M.S. Graduate Program in Evolution, Ecology, and Organismal Biology The Ohio State University 2015 Dissertation Committee: Roman Lanno, Advisor Nicholas Basta Susan Fisher Copyright by Sarah R. Bowman 2015 Abstract With over 4,000 military shooting ranges, and approximately 9,000 non-military shooting ranges within the United States, the Department of Defense and private shooting range owners are challenged with management of these sites. Ammunition used at shooting ranges is comprised mostly of lead (Pb). Shooting ranges result in high soil metal concentrations in small areas and present unique challenges for ecological risk assessment and management. Mean natural background soil Pb is about 32 mg/kg in the eastern United States, but organisms that live in soil or in close association with soil may be at risk from elevated levels of Pb at shooting ranges. Previous shooting range studies on the ecotoxicological impacts of Pb, with few exceptions, used total soil Pb levels as a measure of exposure. However, total soil Pb levels are often not well correlated with Pb toxicity or bioaccumulation. This is a result of differences in Pb bioavailability, or the amount of Pb taken up by an organism that causes a biological response, depending on soil physical/chemical characteristics and species-specific uptake, metabolism, and elimination mechanisms. -

Earthworms (Annelida: Oligochaeta) of the Columbia River Basin Assessment Area

United States Department of Agriculture Earthworms (Annelida: Forest Service Pacific Northwest Oligochaeta) of the Research Station United States Columbia River Basin Department of the Interior Bureau of Land Assessment Area Management General Technical Sam James Report PNW-GTR-491 June 2000 Author Sam Jamesis an Associate Professor, Department of Life Sciences, Maharishi University of Management, Fairfield, IA 52557-1056. Earthworms (Annelida: Oligochaeta) of the Columbia River Basin Assessment Area Sam James Interior Columbia Basin Ecosystem Management Project: Scientific Assessment Thomas M. Quigley, Editor U.S. Department of Agriculture Forest Service Pacific Northwest Research Station Portland, Oregon General Technical Report PNW-GTR-491 June 2000 Preface The Interior Columbia Basin Ecosystem Management Project was initiated by the USDA Forest Service and the USDI Bureau of Land Management to respond to several critical issues including, but not limited to, forest and rangeland health, anadromous fish concerns, terrestrial species viability concerns, and the recent decline in traditional commodity flows. The charter given to the project was to develop a scientifically sound, ecosystem-based strategy for managing the lands of the interior Columbia River basin administered by the USDA Forest Service and the USDI Bureau of Land Management. The Science Integration Team was organized to develop a framework for ecosystem management, an assessment of the socioeconomic biophysical systems in the basin, and an evalua- tion of alternative management strategies. This paper is one in a series of papers developed as back- ground material for the framework, assessment, or evaluation of alternatives. It provides more detail than was possible to disclose directly in the primary documents. -

King George Whiting (Sillaginodes Punctatus)

Parasites of King George whiting (Sillaginodes punctatus) Name: Echinocephalus sp. (larval stage), a nematode Microhabitat: Lives in the intestinal tract Appearance: Rows of spines around the head and a single hook on the tail Pathology: Unknown Curiosity: As Echinocephalus species mature they grow more rows of spines Name: Cardicola sp., digenean flukes commonly called ‘blood fluke’ Microhabitat: Lives in the circulatory system Appearance: Adult worms are ~2mm long Pathology: Unknown Curiosity: This is the first record of these worms from King George whiting and only 2 adults have been found in over 1000 specimens examined Name: A juvenile isopod from the family Gnathiidae Microhabitat: Attaches to the gills of hosts while feeding Appearance: Small, transparent body that becomes red when feeding on blood Pathology: Unknown Curiosity: Only the larval and juvenile stages are parasitic Name: Anaclavella sillaginoides, a parasitic copepod, or ‘sea-louse’ Microhabitat: Attach to the gill arch Appearance: Small, white, circular-shaped body with long trunk-like attachment; females have a pair of egg strings Pathology: Unknown Name: A juvenile acanthocephalan from the family Polymorphidae, commonly called spiny headed worms Microhabitat: Lives in the intestinal track Appearance: Small, neck and head covered in a number of spines (can be retracted inside the body) Pathology: Unknown Curiosity: The shape of the head (proboscis) and the number of spines does not change during development Name: Polylabris sillaginae, flatworm parasites commonly called ‘gill fluke’ Microhabitat: Lives on the gills and feed on blood Appearance: Small, brown coloured worm that has two rows of microscopic clamps Pathology: Unknown. Gill flukes have been associated with anaemia in other fish hosts Further contact: A research initiative supported by: Conditions of use: ----------------------------------------------------- ----------------------------------------------------- ----------------------------------------------------- Emma L. -

OREGON ESTUARINE INVERTEBRATES an Illustrated Guide to the Common and Important Invertebrate Animals

OREGON ESTUARINE INVERTEBRATES An Illustrated Guide to the Common and Important Invertebrate Animals By Paul Rudy, Jr. Lynn Hay Rudy Oregon Institute of Marine Biology University of Oregon Charleston, Oregon 97420 Contract No. 79-111 Project Officer Jay F. Watson U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service 500 N.E. Multnomah Street Portland, Oregon 97232 Performed for National Coastal Ecosystems Team Office of Biological Services Fish and Wildlife Service U.S. Department of Interior Washington, D.C. 20240 Table of Contents Introduction CNIDARIA Hydrozoa Aequorea aequorea ................................................................ 6 Obelia longissima .................................................................. 8 Polyorchis penicillatus 10 Tubularia crocea ................................................................. 12 Anthozoa Anthopleura artemisia ................................. 14 Anthopleura elegantissima .................................................. 16 Haliplanella luciae .................................................................. 18 Nematostella vectensis ......................................................... 20 Metridium senile .................................................................... 22 NEMERTEA Amphiporus imparispinosus ................................................ 24 Carinoma mutabilis ................................................................ 26 Cerebratulus californiensis .................................................. 28 Lineus ruber ......................................................................... -

Onychophorology, the Study of Velvet Worms

Uniciencia Vol. 35(1), pp. 210-230, January-June, 2021 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.15359/ru.35-1.13 www.revistas.una.ac.cr/uniciencia E-ISSN: 2215-3470 [email protected] CC: BY-NC-ND Onychophorology, the study of velvet worms, historical trends, landmarks, and researchers from 1826 to 2020 (a literature review) Onicoforología, el estudio de los gusanos de terciopelo, tendencias históricas, hitos e investigadores de 1826 a 2020 (Revisión de la Literatura) Onicoforologia, o estudo dos vermes aveludados, tendências históricas, marcos e pesquisadores de 1826 a 2020 (Revisão da Literatura) Julián Monge-Nájera1 Received: Mar/25/2020 • Accepted: May/18/2020 • Published: Jan/31/2021 Abstract Velvet worms, also known as peripatus or onychophorans, are a phylum of evolutionary importance that has survived all mass extinctions since the Cambrian period. They capture prey with an adhesive net that is formed in a fraction of a second. The first naturalist to formally describe them was Lansdown Guilding (1797-1831), a British priest from the Caribbean island of Saint Vincent. His life is as little known as the history of the field he initiated, Onychophorology. This is the first general history of Onychophorology, which has been divided into half-century periods. The beginning, 1826-1879, was characterized by studies from former students of famous naturalists like Cuvier and von Baer. This generation included Milne-Edwards and Blanchard, and studies were done mostly in France, Britain, and Germany. In the 1880-1929 period, research was concentrated on anatomy, behavior, biogeography, and ecology; and it is in this period when Bouvier published his mammoth monograph. -

Phylum Onychophora

Lab exercise 6: Arthropoda General Zoology Laborarory . Matt Nelson phylum onychophora Velvet worms Once considered to represent a transitional form between annelids and arthropods, the Onychophora (velvet worms) are now generally considered to be sister to the Arthropoda, and are included in chordata the clade Panarthropoda. They are no hemichordata longer considered to be closely related to echinodermata the Annelida. Molecular evidence strongly deuterostomia supports the clade Panarthropoda, platyhelminthes indicating that those characteristics which the velvet worms share with segmented rotifera worms (e.g. unjointed limbs and acanthocephala metanephridia) must be plesiomorphies. lophotrochozoa nemertea mollusca Onychophorans share many annelida synapomorphies with arthropods. Like arthropods, velvet worms possess a chitinous bilateria protostomia exoskeleton that necessitates molting. The nemata ecdysozoa also possess a tracheal system similar to that nematomorpha of insects and myriapods. Onychophorans panarthropoda have an open circulatory system with tardigrada hemocoels and a ventral heart. As in arthropoda arthropods, the fluid-filled hemocoel is the onychophora main body cavity. However, unlike the arthropods, the hemocoel of onychophorans is used as a hydrostatic acoela skeleton. Onychophorans feed mostly on small invertebrates such as insects. These prey items are captured using a special “slime” which is secreted from large slime glands inside the body and expelled through two oral papillae on either side of the mouth. This slime is protein based, sticking to the cuticle of insects, but not to the cuticle of the velvet worm itself. Secreted as a liquid, the slime quickly becomes solid when exposed to air. Once a prey item is captured, an onychophoran feeds much like a spider. -

On the Nematodes of the Common Earthworm. by Gilbert E

ON THE NBMATODES OF THE COMMON EARTHWORM. 605 On the Nematodes of the Common Earthworm. By Gilbert E. Johnson, M.Sc.(Biim.), University of Birmingham ; Board of Agriculture and Fisheries Research Scholar. (Studies from the Research Department in Agricultural Zoology, University of Birmingham.) With Plate 37 and 2 Text-figures. CONTENTS. PAGE Introduction ...... 605 Occurrence ...... 609 Cultural Methods . .612 Identification . .618 Confusion of Two Species under one name . 619 Anatomy ...... 623 Questions of Sex ...... 627 (1) Analysis and Character of Reproduction . 627 (2) The Sex Ratio . .635 Life-History . .637 (1) Investigation of Problems relating to the Life-Cycle . 637 (2) Probable Course of the Life-Cycle . .647 Summary of Principal Results ... 649 INTRODUCTION. (1) Survey of the Literature. IT has long been a matter of common knowledge that larval Dematodes inhabit the common earthworm, Lum- bricus terrestris, Linn. They are found both in the coelom and in the nephridia. Those occurring in the ccelom 606 GILBERT E. JOHNSON. are enclosed in cysts or capsules, by which movement is restricted or entirely prevented. Those inhabiting the nephridia, on the other hand, are free and active. The en- cysted, ccelomic form has long been known as Rhabditis pellio, having been named by Schneider (1) as early as 1866. The nephridial form is generally believed to be the same species, but it was not mentioned by Schneider, and I have not been able to find that its identity has been deter- mined by any subsequent investigator, as the following brief survey of the literature will show. In 1845 Dujardin, according to Bastian (2), recorded the existence of nematodes in the general body-cavity of the earthworm. -

“Help, There Are Leeches in Our Lake!”

“Help, there are leeches in our lake!” by Andrea LaMoreaux, Vice President, NH LAKES “Help,” pleaded the caller, “Our lake is polluted—it is full of blood-sucking leeches!” As an aquatic biologist, this is one of the various reasons lake-goers call me during the summer, urging me to find someone or something to fix a problem that is ruining their enjoyment of one of New Hampshire’s approximately 1,000 lakes and ponds. “Don’t worry,” I explained, “Rest assured, by no means does the presence of leeches in your lake mean that your lake is polluted.” The caller on the other end of the phone was unconvinced, so I continued, “Leeches are natural organisms that can be found in most of New Hampshire’s lakes. While there are more than 650 species of leeches in North America, there Leeches are most commonly found in shallow areas are only a few species in New Hampshire known to take of lakes among plants, under rocks, sticks, logs, and blood from a person, and that is only if the right attached to decaying leaves. opportunity arises.” At this point, I emailed the caller some information about where leeches are found, what to do if he got bit by a leech, and how to avoid leaches altogether. I never got a return call back, so I guessed his fears were quelled. In case you aren’t convinced that leeches aren’t a problem, or if you are just curious… What are leeches and where are they found? Leeches are scientifically categorized as annelids (segmented worms) and they are closely related to earthworms. -

A New Korean Earthworm (Oligochaeta: Megadrilacea: Megascolecidae)*

Zootaxa 3368: 256–262 (2012) ISSN 1175-5326 (print edition) www.mapress.com/zootaxa/ Article ZOOTAXA Copyright © 2012 · Magnolia Press ISSN 1175-5334 (online edition) A new Korean earthworm (Oligochaeta: Megadrilacea: Megascolecidae)* ROBERT J. BLAKEMORE1,2, TAE SEO PARK1 & HONG-YUL SEO1 1National Institute of Biological Resources (NIBR), Incheon, 404-708, Korea. 2Corresponding author. E-mail: [email protected] *In: Karanovic, T. & Lee, W. (Eds) (2012) Biodiversity of Invertebrates in Korea. Zootaxa, 3368, 1–304. Abstract Amynthas gageodo Blakemore, sp. nov. is described from small Gageo-do Island, offshore to the southwest of the Korean Peninsula in the Yellow Sea. It is an octothecal species (four pairs of spermathecae) comparable to Japanese Amynthas carnosus (Goto & Hatai, 1899) (synonyms: Korean kyamikia Kobayashi, 1934, monstrifera Kobayashi, 1936, sangyeoli Hong & James, 2001, youngtai Hong & James, 2001, kimhaeiensis Hong & James, 2001, sinsiensis Hong & James, 2001, baemsagolensis Hong & James, 2001, Taiwanese monsoonus James et al., 2005) and to Chinese A. pingi (Stephenson, 1925) (synonym: fornicata Gates, 1935). Species associations in its forest litter habitat on the remote island included terrestrial leeches, planarian flatworm predators and other worms. MtDNA COI barcodes indisputably identify types of A. gageodo as a new model for future Korean earthworm species characterizations. Key words: Amynthas, pheretimoid, island biodiversity, Asian endemic invertebrates. Introduction Surveys of invertebrates on Gageo-do Island (~9.2 km2) were conducted by the National Institute of Biological Resources in 2011. Amongst the animals collected were a manifestly new pheretimoid earthworm species as described in this paper. Materials and Methods Specimens were collected by digging and hand-sorting from leaf litter and humic soil.