Understanding Atrocities During the Malayan Emergency

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Number of Soldiers That Joined the Army from Registered Address in Scotland for Financial Years 2014 to 2017

Army Secretariat Army Headquarters IDL 24 Blenheim Building Marlborough Lines Andover Hampshire, SP11 8HJ United Kingdom Ref: FOI2017/10087/13/04/79464 E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.army.mod.uk XXX XXXXXXXXXXX 5 December 2017 XXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXX Dear XXXXXX, Thank you for your email of 14 October in which you clarified your request of 6 October to the following : ‘In particular please clarify what you mean by ‘people from Scotland’. Are you seeking information regarding individuals who identify themselves as being Scottish regardless of where they live now, or people who currently have a Scottish address regardless of their background or country of origin? Please note that for the MOD Joint Personnel Administration, some of the nationality options an individual can record themselves as include ‘British’, ‘Scottish’ or ‘British Scottish’. I was mainly looking for those having joined the Army from a Scottish address as I’m looking at how many people located in Scotland join the Army. Further clarification is required concerning the second part of your request - please clarify if you want Corps and Infantry Regiment (In essence Cap badge) or Corps and Infantry totals. Please note that a proportion of those who joined the untrained strength in 2016 may still be in training. Yes please, looking for Cap Badge of entrants from Scotland should this information exist. Finally please confirm that you require the information for both parts of your request by Financial Years 2014, 2015 & 2016. Yes please, If the information exists for each year then I would be grateful for this. If this is significantly time consuming then 2016 would be sufficient.’ I am treating your correspondence as a request for information under the Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) 2000. -

The Australians in Vietnam 1962-1972

“They Were Hard Nuts”: The Australians in Vietnam, 1962-1972 A focus on the American failure to make maximum use of the Australians’ counterinsurgency tactics in South Vietnam Kate Tietzen Clemson University Abstract: Addressing the need for studies examining the relationship between Commonwealth militaries and the American military, this paper examines the American military’s relationship with the Australian military contingency sent to Vietnam between 1962 and 1972. Analyzing Foreign Relations of the United States (FRUSA) documents, Australian government documents and Australian primary sources including interviews, papers, and autobiographies, this paper argues that the Americans deliberately used the Australian army in South Vietnam for show rather than force. The paper also illustrates American efforts to discredit and ignore Australian counterinsurgency doctrine and tactics; this undertaking only hindered the overall American anti- communist mission in Vietnam. Australia (1) Met all day Sunday (2) They were hard nuts (3) They had a long list of their contributions to Vietnam already (4) Real progress was made with Holt when went upstairs alone and told of the seriousness of the matter (5) Holt told Taylor that he was such a good salesman that he was glad he had not brought his wife to the meeting —Dr. Clark Clifford, meeting with President Lyndon B. Johnson 5 August 19671 While the Viet Minh and the French fought each other during the First Indochina War in Vietnam, Australia was fighting a guerilla-style war in Malaysia in what has been dubbed the “Malayan Emergency” of 1948-1960. In October of 1953, the Australian Defence Committee, the New Zealand Chiefs of Staff and the British Chief of the Imperial General Staff met in Melbourne to air concerns regarding the possibility of Chinese aggression in Southeast Asia.2 The delegation feared Chinese determination for communist control in Southeast Asia, which would threaten the accessibility of strategic raw materials for western powers in the area. -

Regimental Associations

Regimental Associations Organisation Website AGC Regimental Association www.rhqagc.com A&SH Regimental Association https://www.argylls.co.uk/regimental-family/regimental-association-3 Army Air Corps Association www.army.mod.uk/aviation/ Airborne Forces Security Fund No Website information held Army Physical Training Corps Assoc No Website information held The Black Watch Association www.theblackwatch.co.uk The Coldstream Guards Association www.rhqcoldmgds.co.uk Corps of Army Music Trust No Website information held Duke of Lancaster’ Regiment www.army.mod.uk/infantry/regiments/3477.aspx The Gordon Highlanders www.gordonhighlanders.com Grenadier Guards Association www.grengds.com Gurkha Brigade Association www.army.mod.uk/gurkhas/7544.aspx Gurkha Welfare Trust www.gwt.org.uk The Highlanders Association No Website information held Intelligence Corps Association www.army.mod.uk/intelligence/association/ Irish Guards Association No Website information held KOSB Association www.kosb.co.uk The King's Royal Hussars www.krh.org.uk The Life Guards Association No website – Contact [email protected]> The Blues And Royals Association No website. Contact through [email protected]> Home HQ the Household Cavalry No website. Contact [email protected] Household Cavalry Associations www.army.mod.uk/armoured/regiments/4622.aspx The Light Dragoons www.lightdragoons.org.uk 9th/12th Lancers www.delhispearman.org.uk The Mercian Regiment No Website information held Military Provost Staff Corps http://www.mpsca.org.uk -

Klinik Panel Selangor

SENARAI KLINIK PANEL (OB) PERKESO YANG BERKELAYAKAN* (SELANGOR) BIL NAMA KLINIK ALAMAT KLINIK NO. TELEFON KOD KLINIK NAMA DOKTOR 20, JALAN 21/11B, SEA PARK, 1 KLINIK LOH 03-78767410 K32010A DR. LOH TAK SENG 46300 PETALING JAYA, SELANGOR. 72, JALAN OTHMAN TIMOR, 46000 PETALING JAYA, 2 KLINIK WU & TANGLIM 03-77859295 03-77859295 DR WU CHIN FOONG SELANGOR. DR.LEELA RATOS DAN RAKAN- 86, JALAN OTHMAN, 46000 PETALING JAYA, 3 03-77822061 K32018V DR. ALBERT A/L S.V.NICKAM RAKAN SELANGOR. 80 A, JALAN OTHMAN, 4 P.J. POLYCLINIC 03-77824487 K32019M DR. TAN WEI WEI 46000 PETALING JAYA, SELANGOR. 6, JALAN SS 3/35 UNIVERSITY GARDENS SUBANG, 5 KELINIK NASIONAL 03-78764808 K32031B DR. CHANDRAKANTHAN MURUGASU 47300 SG WAY PETALING JAYA, SELANGOR. 6 KLINIK NG SENDIRIAN 37, JALAN SULAIMAN, 43000 KAJANG, SELANGOR. 03-87363443 K32053A DR. HEW FEE MIEN 7 KLINIK NG SENDIRIAN 14, JALAN BESAR, 43500 SEMENYIH, SELANGOR. 03-87238218 K32054Y DR. ROSALIND NG AI CHOO 5, JALAN 1/8C, 43650 BANDAR BARU BANGI, 8 KLINIK NG SENDIRIAN 03-89250185 K32057K DR. LIM ANN KOON SELANGOR. NO. 5, MAIN ROAD, TAMAN DENGKIL, 9 KLINIK LINGAM 03-87686260 K32069V DR. RAJ KUMAR A/L S.MAHARAJAH 43800 DENGKIL, SELANGOR. NO. 87, JALAN 1/12, 46000 PETALING JAYA, 10 KLINIK MEIN DAN SURGERI 03-77827073 K32078M DR. MANJIT SINGH A/L SEWA SINGH SELANGOR. 2, JALAN 21/2, SEAPARK, 46300 PETALING JAYA, 11 KLINIK MEDIVIRON SDN BHD 03-78768334 K32101P DR. LIM HENG HUAT SELANGOR. NO. 26, JALAN MJ/1 MEDAN MAJU JAYA, BATU 7 1/2 POLIKLINIK LUDHER BHULLAR 12 JALAN KLANG LAMA, 46000 PETALING JAYA, 03-7781969 K32106V DR. -

The Malayan Communist Party's Struggle for Hearts and Minds In

No. 116 ‘Voice of the Malayan Revolution’: The Communist Party of Malaya’s Struggle for Hearts and Minds in the ‘Second Malayan Emergency’ (1969-1975) Ong Wei Chong Institute of Defence and Strategic Studies Singapore 13 October 2006 With Compliments This Working Paper series presents papers in a preliminary form and serves to stimulate comment and discussion. The views expressed are entirely the author’s own and not that of the Institute of Defence and Strategic Studies The Institute of Defence and Strategic Studies (IDSS) was established in July 1996 as an autonomous research institute within the Nanyang Technological University. Its objectives are to: • Conduct research on security, strategic and international issues. • Provide general and graduate education in strategic studies, international relations, defence management and defence technology. • Promote joint and exchange programmes with similar regional and international institutions; and organise seminars/conferences on topics salient to the strategic and policy communities of the Asia-Pacific. Constituents of IDSS include the International Centre for Political Violence and Terrorism Research (ICPVTR), the Centre of Excellence for National Security (CENS) and the Asian Programme for Negotiation and Conflict Management (APNCM). Research Through its Working Paper Series, IDSS Commentaries and other publications, the Institute seeks to share its research findings with the strategic studies and defence policy communities. The Institute’s researchers are also encouraged to publish their writings in refereed journals. The focus of research is on issues relating to the security and stability of the Asia-Pacific region and their implications for Singapore and other countries in the region. The Institute has also established the S. -

Alasek 31 Jan 08 Utk Edaran

SENARAI MAKLUMAT SEKOLAH NEGERI SELANGOR DAERAH : HULU SELANGOR BIL BANTUAN LOKASI GRED KODSEK SEKOLAH ALAMAT POSKOD BANDAR TELEFON FAKS SK 1 Sek Kerajaan Bandar Kecil A BBA5002 SK BATANG KALI JALAN ULU YAM BHARU 44300 BATANG KALI 03-60572157 03-60472157 2 Sek Kerajaan Bandar Kecil A BBA5003 SK RASA KG KAMPUNG SEKOLAH 44200 RASA 03-60572052 03-60572052 3 Sek Kerajaan Bandar Kecil A BBA5004 SK SG CHOH KAMPUNG SUNGAI CHOH 48000 RAWANG 03-60918661 03-60918661 4 Sek Kerajaan Luar Bandar A BBA5005 SK SG SELISEK KAMPUNG SUNGAI SELISEK 44020 KUALA KUBU BHARU 05-4543358 05-4543358 5 Sek Kerajaan Luar Bandar A BBA5006 SK ULU YAM BHARU JALAN ULU YAM BATANG KALI 44300 BATANG KALI 03-60752978 03-60752979 6 Sek Kerajaan Luar Bandar B BBA5007 SK ULU YAM LAMA KG.ULU YAM LAMA 44300 BATANG KALI 03-60752117 603-6072117 7 Sek Kerajaan Bandar Kecil A BBA5008 SK HULU BERNAM KAMPUNG BARU 'B' 35900 TANJUNG MALIM 05-4596787 6054596787 8 Sek Kerajaan Bandar Kecil A BBA5009 SK KUALA KUBU BHARU JALAN SEKOLAH 44000 KUALA KUBU BHARU 03-60641482 03-60641482 9 Sek Kerajaan Bandar Kecil A BBA5010 SK KERLING KAMPUNG KERLING 44100 KERLING 03-60482032 03-60482032 10 Sek Kerajaan Luar Bandar A BBA5011 SK KALUMPANG KAMPUNG KALUMPANG 44100 KERLING 03-60491866 03-60491866 11 Sek Kerajaan Luar Bandar A BBA5012 SK KG KUANTAN KAMPUNG KUANTAN 44300 BATANG KALI 03-60571848 03-60571848 12 Sek Kerajaan Luar Bandar A BBA5013 SK GEDANGSA FELDA GEDANGSA 44020 KUALA KUBU BHARU 03-60463616 03-60463616 13 Sek Kerajaan Luar Bandar A BBA5014 SK SUNGAI BUAYA KG SUNGAI BUAYA 48010 RAWANG 03-60282010 -

Decolonization in the British Empire at the End of the Second World War, Britain Still Controlled the Largest Empire in World History

Decolonization in the British Empire At the end of the Second World War, Britain still controlled the largest empire in world history. Thanks largely to the empire, Britain raised enough supplies to sustain its war effort and took its place at the top table of the victorious powers alongside the United States and the Soviet Union. It was, however, a Pyrrhic victory; the war drained Britain’s finances and significantly lowered its prestige in the colonies. Less than two decades later, the British had given up almost all of their empire. This reading examines the period from 1945 to 1963, when the British surrendered almost all of their overseas colonies. There will be special focus on India, Kenya, Malaya (Malaysia), and Egypt. Finally, we will examine the legacy of empire for today’s Britain. The Effects of the Second World War The experience of the Second World War was not the sole reason that Britain eventually lost its colonies, but without the war the decolonization process doubtless would have taken longer. It is worth noting, however, that the origins of nationalist and anticolonial revolt across the British Empire were often rooted in the early twentieth century. After the First World War, British imperialists still preached about the superiority of Western (especially British) civilization, but their arguments often fell on deaf ears. Many subject peoples, especially Indians, had fought on the Western Front in the First World War. They saw that the British were no more immune to machine guns than any other group of people. They also observed Britain’s weakened state after the First World War and during the economic crisis of the 1930s. -

Mainx Alc 0207 Klang Valley Train Route

Klang Valley Rail Map Batu Caves Batu Caves–Tampin Tanjung Malim KTM Komuter Kuala Kubu Baru Rasa Tanjung Malim–Port Klang Batang Kali KTM Komuter Taman Wahyu Serendah Gombak Rawang LRT Ampang Line Kuang Taman Melati Wangsa Maju Kg Batu Sungai Buloh LRT Sri Petaling Line Sri Rampai Setiawangsa LRT Kelana Jaya Line Kepong Jelatek Sentral Sentul Timur Batu Kentonmen Dato Keramat Kampung Kepong Selamat ERL Klia Express Sentul Sentul Ampang Damai Kwasa Damansara Cahaya ERL Klia Transit Segambut Titiwangsa Ampang Park Cempaka KLCC Chow Kit KL Monorail Pandan Indah Kwasa Sentral Medan Putra PWTC Tuanku Kampung Baru MRT Sg Buloh-Kajang Line Pandan Jaya Kota Damansara Dang Bukit Nanas Wangi Sultan Ismail Raja Chulan Surian BRT Sunway Line Bukit Bintang Maluri Mutiara Damansara Tun Razak Cochrane Taman Note: The proposed MRT2, LRT3 and Bank Negara Bandaraya Exchange Pertama Klang BRT are not in this map Taman Bandar Utama Imbi Masjid Merdeka Midah ©The Star Graphics Miharja Taman Tun Jamek Hang Tuah Pudu Taman Dr Ismail Chan Sow Lin Mutiara Plaza Phileo Rakyat Taman Damansara Kuala Lumpur Pasar Maharajalela Cheras Seni Connaught Pusat Bandar Semantan Muzium Taman Tun Sambanthan Damansara Negara Salak Selatan Suntex KL Sentral Sri Raya Midvalley Bandar Tun Hussein Onn Bangsar Seputeh Abdullah Bandar Tun Razak Batu 11 Cheras KL Eco City (future) Salak Hukum Lembah Kelana Taman Taman Selatan Subang Jaya Bahagia Paramount Kerinchi Angkasapuri Bukit Dukung Bandar Tasik Terminal Pantai Dalam Bersepadu Skypark Terminal Asia Taman Selatan Ara Petaling -

Senarai Stesen Rel Bandar (Semenanjung Malaysia)

Senarai Stesen Rel Bandar (Semenanjung Malaysia) Perkhidmatan Bil.Nama Stesen ID StesenNegeri Pihak Berkuasa Tempatan 1Gombak KJ1 WP KL DBKL 2Taman Melati KJ2 WP KL DBKL 3Wangsa Maju KJ3 WP KL DBKL 4Sri Rampai KJ4 WP KL DBKL 5Setiawangsa KJ5 WP KL DBKL 6Jelatek KJ6 WP KL DBKL 7Dato' Keramat KJ7 WP KL DBKL 8Damai KJ8 WP KL DBKL 9Ampang Park KJ9 WP KL DBKL 10KLCC KJ10 WP KL DBKL 11Kampung Baru KJ11 WP KL DBKL 12Dang Wangi KJ12 WP KL DBKL 13Masjid Jamek KJ13 WP KL DBKL 14Pasar Seni KJ14 WP KL DBKL 15KL Sentral KJ15 WP KL DBKL 16Bangsar KJ16 WP KL DBKL 17Abdullah Hukum KJ17 WP KL DBKL 18Kerinchi KJ18 WP KL DBKL LRT KJ Line 19Universiti KJ19 WP KL DBKL 20Taman Jaya KJ20 Selangor Petaling Jaya 21Asia Jaya KJ21 Selangor Petaling Jaya 22Taman Paramount KJ22 Selangor Petaling Jaya 23Taman Bahagia KJ23 Selangor Petaling Jaya 24Kelana Jaya KJ24 Selangor Petaling Jaya 25Lembah Subang KJ25 Selangor Petaling Jaya 26Ara Damansara KJ26 Selangor Petaling Jaya 27Glenmarie KJ27 Selangor Shah Alam 28Subang Jaya KJ28 Selangor Subang Jaya 29SS15 KJ29 Selangor Subang Jaya 30SS18 KJ30 Selangor Subang Jaya 31USJ7 KJ31 Selangor Subang Jaya 32Taipan KJ32 Selangor Subang Jaya 33Wawasan KJ33 Selangor Subang Jaya 34USJ21 KJ34 Selangor Subang Jaya 35Alam Megah KJ35 Selangor Subang Jaya 36Subang Alam KJ36 Selangor Subang Jaya 37Putra Heights KJ37 Selangor Subang Jaya 1Sentul Timur AG1/SP1WP KL DBKL 2Sentul AG2/SP2WP KL DBKL 3Titiwangsa AG3/SP3WP KL DBKL 4PWTC AG4/SP4WP KL DBKL 5Sultan Ismail AG5/SP5WP KL DBKL 6Bandaraya AG6/SP6WP KL DBKL 7Masjid Jamek AG7/SP7WP KL DBKL -

Scottish Division Queen's Division King's Division

MINSTRY OF DEFENCE Short Service Commissions Intermediate Regular Commissions (Late Entry) Lieutenant A. W. BUDGE Welsh Guards 25231720 to be Captain Warrant Officer Class 1 Myles Justin DAVID Royal Anglian Regiment 13 February 2014 24818864 to be Captain 2 April 2014 Lieutenant M. W. S. DOBSON Grenadier Guards 30038909 to be Warrant Officer Class 2 Robert MURRAY Princess of Wales’s Royal Captain 13 February 2014 Regiment 25030163 to be Captain 2 April 2014 Lieutenant A. E. FLOYD Irish Guards 30109395 to be Captain Short Service Commissions 13 February 2014 Lieutenant L. M. FLYNN Princess of Wales’s Royal Regiment Lieutenant J. A. L. GARTON Grenadier Guards 562649 to be Captain 30028278 to be Captain 13 February 2014 13 February 2014 Lieutenant R. A. ILLING Royal Regiment of Fusiliers 25232167 to be Lieutenant A. J. HAMILTON Irish Guards 25233665 to be Captain Captain 13 February 2014 13 February 2014 Lieutenant A. C. PETERS Royal Anglian Regiment 25232039 to be Lieutenant T. W. J. HUTTON Welsh Guards 25232822 to be Captain Captain 13 February 2014 13 February 2014 Lieutenant P. M. RICHARDSON Royal Regiment of Fusiliers 30028259 Lieutenant A. MAXWELL-SCOTT Scots Guards 30128053 to be to be Captain 13 February 2014 Captain 13 February 2014 Lieutenant A. J. E. SMITH Royal Anglian Regiment 30028234 to be Lieutenant F. C. B. MOYNAN Grenadier Guards 30030417 to be Captain 13 February 2014 Captain 13 February 2014 Lieutenant C. H. TREZISE Princess of Wales’s Royal Regiment Lieutenant H. R. W. HARDY Grenadier Guards 30121990 to be 30120076 to be Captain 13 February 2014 Captain 16 April 2014 REGULAR ARMY RESERVE OF OFFICERS SCOTTISH DIVISION Short Service Commissions REGULAR ARMY Captain E. -

The Queen's Guard

The Queen's Guard By Dolores Eamets, Silver Põlgaste and Liina Reimann Who is The Queen´s Guard? ● The Queen's Guard is the name given to the contingent of infantry responsible for guarding Buckingham Palace and St James' Palace in London. ● The guard is made up of a company of soldiers from a single regiment, which is split in two, providing a detachment for Buckingham Palace and a detachment for St James' Palace. ● The Guards have served ten Kings and four Queens. History ● The Queen's Guard have served Sovereign and the Royal Palaces since 1660. ● Until 1689, the Sovereign lived mainly at the Palace of Whitehall and was guarded there by Household Cavalry. ● In 1689, the court moved to St James' Palace, which was guarded by the Foot Guards. ● When Queen Victoria moved into Buckingham Palace in 1837, the Queen's Guard remained at St James' Palace, with a detachment guarding Buckingham Palace, as it still does today. The Household Cavalry Regiments There are two Household Cavalry Regiments - The Life Guards and The Blues and Royals. The Guard changing ceremony at Buckingham Palace ● It takes place at 11.30 am. ● The handover is accompanied by a Guards band. ● It is also known as ‘Guard Mounting’. ● The New Guard, who during the course of the ceremony become The Queen’s Guard, march to Buckingham Palace from Wellington Barracks. ● During the Changing the Guard ceremony one regiment takes over from another. The Guard changing ceremony at St James' Palace • It takes place daily at 11.00 am (10.00 am on Sundays). -

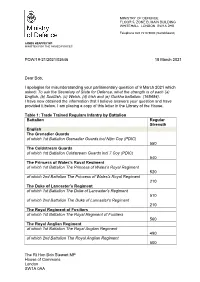

The Rt Hon Bob Stewart MP House of Commons London SW1A 0AA PQW

MINISTRY OF DEFENCE FLOOR 5, ZONE B, MAIN BUILDING WHITEHALL LONDON SW1A 2HB Telephone 020 7218 9000 (Switchboard) JAMES HEAPPEY MP MINISTER FOR THE ARMED FORCES PQW/19-21/2021/02646 18 March 2021 Dear Bob, I apologise for misunderstanding your parliamentary question of 9 March 2021 which asked: To ask the Secretary of State for Defence, what the strength is of each (a) English, (b) Scottish, (c) Welsh, (d) Irish and (e) Gurkha battalion. (165484). I have now obtained the information that I believe answers your question and have provided it below. I am placing a copy of this letter in the Library of the House. Table 1: Trade Trained Regulars Infantry by Battalion Battalion Regular Strength English The Grenadier Guards of which 1st Battalion Grenadier Guards incl Nijm Coy (PDIC) 550 The Coldstream Guards of which 1st Battalion Coldstream Guards incl 7 Coy (PDIC) 540 The Princess of Wales's Royal Regiment of which 1st Battalion The Princess of Wales's Royal Regiment 520 of which 2nd Battalion The Princess of Wales's Royal Regiment 210 The Duke of Lancaster's Regiment of which 1st Battalion The Duke of Lancaster's Regiment 510 of which 2nd Battalion The Duke of Lancaster's Regiment 210 The Royal Regiment of Fusiliers of which 1st Battalion The Royal Regiment of Fusiliers 560 The Royal Anglian Regiment of which 1st Battalion The Royal Anglian Regiment 490 of which 2nd Battalion The Royal Anglian Regiment 500 The Rt Hon Bob Stewart MP House of Commons London SW1A 0AA The Yorkshire Regiment of which 1st Battalion The Yorkshire Regiment 510