Lost Learning: Why We Need to Level up Education

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Coronavirus Bill 23 March 2020 Volume 674 the Chairman of Ways

25/03/2020 Coronavirus Bill - Hansard Cookies: We use cookies to give you the best possible experience on our site. By continuing to use OK the site you agree to our use of cookies. Find out more Coronavirus Bill Share 23 March 2020 Volume 674 Proceedings resumed (Order, this day). Considered in Committee (Order, this day). [Dame Eleanor Laing in the Chair] The Chairman of Ways and Means (Dame Eleanor Laing) I have a few things to explain before we begin Committee stage. For understandable reasons, a large number of manuscript amendments have been tabled by the Government today, and in fact a large number of other manuscript amendments have, unusually, been allowed today as well. Members therefore need to make sure that they are working from the right version of the notice paper and that they have the latest version of the grouping and selection list, although I should explain that there is one group. Government amendments 79 to 82 on extradition are on a separate supplementary notice paper, and a revised grouping and selection list will be issued shortly. The late appearance of these amendments is due not to Government action but to a mistake on the part of the Public Bill Ofce, but, lest anybody complain, I will defend the Public Bill Ofce, because they have done a marvellous job today. I have seen it over the last few days, and the people who work here have worked miracles to get us to this stage in such good order. The Business of the House motion, which the House agreed before Second Reading, allows the Chair discretion at the end of the time allowed for Committee—in this case, that falls at exactly 10 pm—to call non-Government amendments and new clauses to be moved formally https://hansard.parliament.uk/Commons/2020-03-23/debates/1BF3C655-EAD2-45DF-BAE2-30052908F7E6/CoronavirusBill 1/122 25/03/2020 Coronavirus Bill - Hansard at that stage for separate decision. -

Committee of the Whole House Proceedings

1 House of Commons Thursday 11 February 2021 COMMITTEE OF THE WHOLE HOUSE PROCEEDINGS MINISTERIAL AND OTHER MATERNITY ALLOWANCES BILL GLOSSARY This document shows the fate of each clause, schedule, amendment and new clause. The following terms are used: Added: New Clause agreed without a vote and added to the Bill. Agreed to: agreed without a vote. Agreed to on division: agreed following a vote. Negatived: rejected without a vote. Negatived on division: rejected following a vote. Not called: debated in a group of amendments, but not put to a decision. Not moved: not debated or put to a decision. Question proposed: debate underway but not concluded. Withdrawn after debate: moved and debated but then withdrawn, so not put to a decision. Not selected: not chosen for debate by the Chair. Kirsten Oswald Negatived 3 Clause 1,page1, line 5, leave out “may” and insert “must” 2 Committee of the whole House Proceedings: 11 February 2021 Ministerial and Other Maternity Allowances Bill, continued Jackie Doyle-Price Sir John Hayes Ben Bradley Tonia Antoniazzi Rosie Duffield Cherilyn Mackrory Andrew Rosindell Fiona Bruce Stephen Metcalfe Bob Blackman Not called 15 Clause 1,page1, line 5, leave out “a person as” Jackie Doyle-Price Sir John Hayes Ben Bradley Tonia Antoniazzi Rosie Duffield Cherilyn Mackrory Andrew Rosindell Fiona Bruce Stephen Metcalfe Bob Blackman Not called 16 Clause 1,page1, line 14, leave out “person” and insert “minister” Sir John Hayes Miriam Cates Lee Anderson Alexander Stafford Ben Bradley Tom Hunt Sir Edward Leigh Karl McCartney -

E-Petition Session: TV Licensing, HC 1233

Petitions Committee Oral evidence: E-petition session: TV Licensing, HC 1233 Monday 1 March 2021 Ordered by the House of Commons to be published on 1 March 2021. Watch the meeting Members present: Catherine McKinnell (Chair); Tonia Antoniazzi; Jonathan Gullis. Other Members present: Rosie Cooper; Damian Collins; Gill Furniss; Gareth Bacon; Jamie Stone; Ben Bradley; Tahir Ali; Brendan Clarke-Smith; Allan Dorans; Virginia Crosbie; Mr Gregory Campbell; Simon Jupp; Jeff Smith; Huw Merriman; Chris Bryant; Mark Eastwood; Ian Paisley; John Nicolson; Chris Matheson; Rt Hon Mr John Whittingdale OBE, Minister for Media and Data. Questions 1-21 Chair: Thank you all for joining us today. Today’s e-petition session has been scheduled to give Members from across the House an opportunity to discuss TV licensing. Sessions like this would normally take place in Westminster Hall, but due to the suspension of sittings, we have started holding these sessions as an alternative way to consider the issues raised by petitions and present these to Government. We have received more requests to take part than could be accommodated in the 90 minutes that we are able to schedule today. Even with a short speech limit for Back- Bench contributions, it shows just how important this issue is to Members right across the House. I am pleased to be holding this session virtually, and it means that Members who are shielding or self-isolating, and who are unable to take part in Westminster Hall debates, are able to participate. I am also pleased that we have Front-Bench speakers and that we have the Minister attending to respond to the debate today. -

What Does Ocean Recovery Mean for Your Constituency?

What does Ocean Recovery mean for your Constituency? 16th September 2020 Virtual Meeting: Zoom 10am – 11am ATTENDEES Steve Double MP (Chair) (SD) Oliver Kerr Communications & Hugo Tagholm, CEO Surfers Engagement Manager to Against Sewage (HT) Selaine Saxby MP (OK) Kerry McCarthy MP (Vice Sam Browse Chris Tuckett, Chair of Marine Chair) (KM) Senior Parliamentary Assistant Group at the Wildlife and to Olivia Blake MP (SB) Countryside Link (CT) Cherilyn Mackrory MP (Vice Elinor Cope Parliamentary Alec Taylor, Head of Ocean Chair) (CM) Assistant to Policy WWF UK (AT) Caroline Dinenage MP (EC) Scott Mann MP (Treasurer) Nicole Zandi Senior Ruth Williams, Marine (SM) Parliamentary Assistant to Conservation Manager, Geraint Davies MP (NZ) Cornwall Wildlife Trust (RW) Sir Peter Bottomley MP Huw David for Cherilyn Alice Tebb, Agents for Change (PB) Mackrory MP (HD) Coordinator, Marine Conservation Society (AT) Martyn Day MP Samuel Yung Senior Henry Swithinbank, Surfers (MD) Parliamentary Assistant Against Sewage (HS) to Steve Double MP (SY) Liz Twist MP Chad Male Parliamentary Amy Slack, Surfers Against (LT) Assistant Sewage (AS) to Liz Twist MP (CM) Stephen Crabb MP Natasha Ikners Senior Alice Field, Surfers Against (SC) Parliamentary Assistant to Sewage (AF) Duncan Baker MP(NI) Duncan Baker MP Richard Watt Matt Browne, Wildlife and (DB) Parliamentary Assistant to Countryside Link (MB) Stephen Crabb MP (RW) Megan Randles, WWF UK (MR) Tamara Abidi – WWF UK (TA) MINUTES Welcome and Opening Remarks Steve Double MP, Chair of the APPG welcomed the attendees to the first ever digital Ocean Conservation APPG and set out the role of the group as the voice of the ocean in parliament. -

Fighting Economic Crime - a Shared Responsibility!

THIRTY-SEVENTH INTERNATIONAL SYMPOSIUM ON ECONOMIC CRIME SUNDAY 1st SEPTEMBER - SUNDAY 8th SEPTEMBER 2019 JESUS COLLEGE, UNIVERSITY OF CAMBRIDGE Fighting economic crime - a shared responsibility! Centre of Development Studies The 37th Cambridge International Symposium on Economic Crime Fighting economic crime- a shared responsibility! The thirty-seventh international symposium on economic crime brings together, from across the globe, a unique level and depth of expertise to address one of the biggest threats facing the stability and development of all our economies. The overarching theme for the symposium is how we can better and more effectively work together in preventing, managing and combating the threat posed by economically motivated crime and abuse. The programme underlines that this is not just the responsibility of the authorities, but us all. These important and timely issues are considered in a practical, applied and relevant manner, by those who have real experience whether in law enforcement, regulation, compliance or simply protecting their own or another’s business. The symposium, albeit held in one of the world’s leading universities, is not a talking shop for those with vested interests or for that matter an academic gathering. We strive to offer a rich and deep analysis of the real issues and in particular threats to our institutions and economies presented by economic crime and abuse. Well over 700 experts from around the world will share their experience and knowledge with other participants drawn from policy makers, law enforcement, compliance, regulation, business and the professions. The programme is drawn up with the support of a number of agencies and organisations across the globe and the Organising Institutions and principal sponsors greatly value this international commitment. -

A Guide to the Government for BIA Members

A guide to the Government for BIA members Correct as of 26 June 2020 This is a briefing for BIA members on the Government led by Boris Johnson and key ministerial appointments for our sector after the December 2019 General Election and February 2020 Cabinet reshuffle. Following the Conservative Party’s compelling victory, the Government now holds a majority of 80 seats in the House of Commons. The life sciences sector is high on the Government’s agenda and Boris Johnson has pledged to make the UK “the leading global hub for life sciences after Brexit”. With its strong majority, the Government has the power to enact the policies supportive of the sector in the Conservatives 2019 Manifesto. All in all, this indicates a positive outlook for life sciences during this Government’s tenure. Contents: Ministerial and policy maker positions in the new Government relevant to the life sciences sector .......................................................................................... 2 Ministers and policy maker profiles................................................................................................................................................................................................ 7 Ministerial and policy maker positions in the new Government relevant to the life sciences sector* *Please note that this guide only covers ministers and responsibilities relevant to the life sciences and will be updated as further roles and responsibilities are announced. Department Position Holder Relevant responsibility Holder in -

Agenda, Tuesday 3Rd March 2020

Bishop Auckland Town Council The Four Clocks Centre, 154a Newgate Street, Bishop Auckland, Co. Durham DL14 7EH Tel: 01388 609852 Email: [email protected] Website: www.bishopauckland-tc.gov.uk Town Clerk: David Anderson TO: ALL MEMBERS OF THE COUNCIL 26th February 2020 Dear Councillor, I hereby give you notice that the next meeting of Bishop Auckland Town Council will be held in the Wesley Room at The Four Clocks Centre on Tuesday, 3rd March 2020 at 6.00 p.m. Yours sincerely David Anderson Clerk to the Council AGENDA 1. Apologies for absence 2. Declarations of Interest To invite members to declare any interest they may have. 3. Public Participation (Subject to Public Participation Policy) Presentations Time Allocation* *The Mayor will be flexible with the amount of time allocated where it is helpful to the debate. 4. Town Team 1. Core Team (Chairman, Nigel Bryson) 10 mins presentation 2. Events Team (Chairman, Clive Auld) 5 mins questions 5. Minutes To approve the Minutes of the following meetings:- Town Council 21st January 2020 Planning Committee 21st January 2020 Human Resources Committee 11th February 2020 Town Council 18th February 2020 Finance Committee 25th February 2020 6. Matters Arising To receive any matters arising from the above Minutes which are not included elsewhere on the agenda (for information only). 1 - 39 7. Report of Mayor To receive a report from the Mayor detailing activities attended to represent the Council since the Annual Meeting. 8. Report of Town Clerk 1. Bishop Auckland Town Team, Request to Draw Down Funds 2. Bishop Auckland Town Team, Request for Funding 3. -

View Future Day Orals PDF File 0.11 MB

Published: Friday 4 December 2020 Questions for oral answer on a future day (Future Day Orals) Questions for oral answer on a future day as of Friday 4 December 2020. The order of these questions may be varied in the published call lists. [R] Indicates that a relevant interest has been declared. Questions for Answer on Monday 7 December Oral Questions to the Secretary of State for Defence Allan Dorans (Ayr, Carrick and Cumnock): What plans he has for future military and security co-operation with EU (a) institutions and (b) member states. (909779) Jessica Morden (Newport East): What steps he is taking to increase the take-up of UK-produced steel in defence procurement. (909780) Sir David Amess (Southend West): What steps he is taking to ensure that his Department’s spending supports (a) high-skilled jobs and (b) the wider UK economy. (909781) Fleur Anderson (Putney): What support his Department has provided to veterans during the covid-19 outbreak. (909782) Holly Mumby-Croft (Scunthorpe): What recent preparations his Department has made to support (a) the NHS and (b) other public bodies in their response to the covid-19 outbreak. (909783) David Simmonds (Ruislip, Northwood and Pinner): What recent preparations his Department has made to support (a) the NHS and (b) other public bodies in their response to the covid-19 outbreak. (909784) Christine Jardine (Edinburgh West): What recent assessment he has made of the effectiveness of his Department's official development assistance spending. (909785) Andrew Jones (Harrogate and Knaresborough): What recent assessment he has made of the potential merits of including armed forces veterans in the UK’s response to the covid-19 outbreak. -

MIDLANDS MATTERS ISSUE 3 Midlandsengine.Org

MIDLANDS MATTERS ISSUE 3 midlandsengine.org Welcome to an earlier than planned third to adjust, try to keep fit and healthy and establish edition of our partnership newsletter, a new work-life balance. Midlands Matters. And with so many simply extraordinary We are living through unprecedented times - responses from partner organisations right and Covid-19 is a challenge to us all, on both across Midlands Engine, on work to combat the individual and organisational levels. I would like virus in a medical and clinical setting - I wanted to take this opportunity to personally send you to share with you the remarkable work of those my very best wishes, and hope that you, your teams involved here too. From donating supplies colleagues and your families are well and remain of personal protective equipment, to producing so in coming weeks. hand sanitiser on an industrial scale, helping DNA sequencing of the virus and providing But there are positives we can find in this testing kits, the Midlands has truly delivered situation - and the early issue of this newsletter when called upon - and will continue to do so. is here to recognise the phenomenal work that is going on in our partnership on a day- I hope this positive news bring a small reprieve by-day basis to help with the fight against to the heavy workloads we are all carrying Covid-19. Partners across the region have been right now, and serves as an uplifting reminder contributing to the cause in all manner of ways that there is great work going on to defeat the and I wanted to share just some of these stories virus. -

Foresight Hindsight

Hindsight, Foresight ThinkingI Aboutnsight, Security in the Indo-Pacific EDITED BY ALEXANDER L. VUVING DANIEL K. INOUYE ASIA-PACIFIC CENTER FOR SECURITY STUDIES HINDSIGHT, INSIGHT, FORESIGHT HINDSIGHT, INSIGHT, FORESIGHT Thinking About Security in the Indo-Pacific Edited by Alexander L. Vuving Daniel K. Inouye Asia-Pacific Center for Security Studies Hindsight, Insight, Foresight: Thinking About Security in the Indo-Pacific Published in September 2020 by the Daniel K. Inouye Asia-Pacific Center for Security Studies, 2058 Maluhia Rd, Honolulu, HI 96815 (www.apcss.org) For reprint permissions, contact the editors via [email protected] Printed in the United States of America Cover Design by Nelson Gaspar and Debra Castro Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Name: Alexander L. Vuving, editor Title: Hindsight, Insight, Foresight: Thinking About Security in the Indo-Pacific / Vuving, Alexander L., editor Subjects: International Relations; Security, International---Indo-Pacific Region; Geopolitics---Indo-Pacific Region; Indo-Pacific Region JZ1242 .H563 2020 ISBN: 978-0-9773246-6-8 The Daniel K. Inouye Asia-Pacific Center for Security Studies is a U.S. Depart- ment of Defense executive education institution that addresses regional and global security issues, inviting military and civilian representatives of the United States and Indo-Pacific nations to its comprehensive program of resident courses and workshops, both in Hawaii and throughout the Indo-Pacific region. Through these events the Center provides a focal point where military, policy-makers, and civil society can gather to educate each other on regional issues, connect with a network of committed individuals, and empower themselves to enact cooperative solutions to the region’s security challenges. -

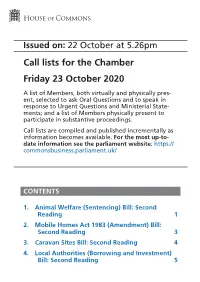

(Amendment) Bill: Second Reading 3 3

Issued on: 22 October at 5.26pm Call lists for the Chamber Friday 23 October 2020 A list of Members, both virtually and physically pres- ent, selected to ask Oral Questions and to speak in response to Urgent Questions and Ministerial State- ments; and a list of Members physically present to participate in substantive proceedings. Call lists are compiled and published incrementally as information becomes available. For the most up-to- date information see the parliament website: https:// commonsbusiness.parliament.uk/ CONTENTS 1. Animal Welfare (Sentencing) Bill: Second Reading 1 2. Mobile Homes Act 1983 (Amendment) Bill: Second Reading 3 3. Caravan Sites Bill: Second Reading 4 4. Local Authorities (Borrowing and Investment) Bill: Second Reading 5 2 Call lists for the Chamber Friday 23 October 2020 ANIMAL WELFARE (SENTENCING) BILL: SECOND READING Debate on the Second Reading of the Animal Welfare (Sentencing) Bill is expected to start at 9.35am and may not continue after 2.30pm. It is expected to conclude at about 1.45pm. Order Member Debate Party 1 Chris Loder (West Animal Welfare (Sentenc- Con Dorset) ing) Bill: Second Reading 2 Kerry McCarthy (Bristol Animal Welfare (Sentenc- Lab East) ing) Bill: Second Reading 3 Neil Parish (Tiverton and Animal Welfare (Sentenc- Con Honiton) ing) Bill: Second Reading 4 Sir Christopher Chope Animal Welfare (Sentenc- Con (Christchurch) ing) Bill: Second Reading 5 Mark Jenkinson (Work- Animal Welfare (Sentenc- Con ington) ing) Bill: Second Reading 6 Sir David Amess (Sou- Animal Welfare (Sentenc- Con thend -

Daily Report Thursday, 14 January 2021 CONTENTS

Daily Report Thursday, 14 January 2021 This report shows written answers and statements provided on 14 January 2021 and the information is correct at the time of publication (06:29 P.M., 14 January 2021). For the latest information on written questions and answers, ministerial corrections, and written statements, please visit: http://www.parliament.uk/writtenanswers/ CONTENTS ANSWERS 7 Police and Crime BUSINESS, ENERGY AND Commissioners: Elections 15 INDUSTRIAL STRATEGY 7 Schools: Procurement 16 Additional Restrictions Grant 7 Veterans: Suicide 16 Business: Coronavirus 7 DEFENCE 17 Business: Grants 8 Armed Forces: Health Conditions of Employment: Services 17 Re-employment 9 Defence: Expenditure 17 Industrial Health and Safety: HMS Montrose: Repairs and Coronavirus 9 Maintenance 18 Motor Neurone Disease: HMS Queen Elizabeth: Research 10 Repairs and Maintenance 18 Podiatry: Coronavirus 11 DIGITAL, CULTURE, MEDIA AND Public Houses: Coronavirus 11 SPORT 19 Wind Power 12 British Telecom: Disclosure of Information 19 CABINET OFFICE 13 Broadband: Elmet and Civil Servants: Business Rothwell 20 Interests 13 Broadband: Greater London 20 Coronavirus: Disease Control 13 Chatterley Whitfield Colliery 21 Coronavirus: Lung Diseases 13 Data Protection 22 Debts 14 Educational Broadcasting: Fisheries: UK Relations with Coronavirus 23 EU 14 Events Industry and Iron and Steel: Procurement 14 Performing Arts: Greater National Security Council: London 23 Coronavirus 15 Football: Dementia 24 Football: Gambling 24 Organic Food: UK Trade with Freedom of Expression