NEASC Self-Study Team Combined Efforts to Propose Methods for Capturing More Direct Measures of Student Learning Outcomes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Curriculum Vitae

January 2021 Curriculum Vitae Rajiv Vohra Ford Foundation Professor of Economics Brown University Providence, RI 02912 rajiv [email protected] http://www.brown.edu/Departments/Economics/Faculty/Rajiv Vohra Education Ph.D. (Economics), 1983, Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, Maryland. M.A. (Economics), 1981, Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, Maryland. M.A. (Economics), 1979, Delhi School of Economics, University of Delhi, India. B.A. (Economics Hons.), 1977, St. Stephen's College, University of Delhi, India. Current Position Ford Foundation Professor of Economics, Brown University, July 2006 - Other Positions Dean of the Faculty, Brown University, July 2004 - June 2011. Professor of Economics, Brown University, July 1989 - June 2006. Morgenstern Visiting Professor of Economic Theory, New York University, Fall 2001. Fulbright Research Scholar, Indian Statistical Institute, 1995-1996. Chairman, Department of Economics, Brown University, July 1991 - June 1995. Visiting Fellow, Indian Statistical Institute, New Delhi, August 1987 - July 1988. Associate Professor of Economics, Brown University, January 1987 - June 1989. Assistant Professor of Economics, Brown University, July 1983 - December 1986. 1 Professional Activities Associate Editor, Journal of Public Economic Theory, 2017 - . Co-Organizer, 2016, NSF-CEME Decentralization Conference, Brown Uni- versity. Organizer, Conference in Honor of M. Ali Khan, Johns Hopkins University, 2013. Associate Editor, International Journal of Game Theory, 2003 - 2009. Associate Editor, Journal of Mathematical Economics, 1994 - 2009. Associate Editor, Journal of Public Economic Theory, 2001 - 2005. Member, Program Committee, World Congress of the Econometric Society, 2005. Co-Chair, Program Committee, 2004 Econometric Society North American Summer Meetings, Brown University. Co-Organizer, 2001 NSF-CEME General Equilibrium Conference, Brown University. Organizer, 1994 NSF-CEME General Equilibrium Conference, Brown Uni- versity. -

September 29, 2020 Name: Daniel P. Dickstein, MD

The Faculty of Medicine of Harvard University Curriculum Vitae Date Prepared: September 29, 2020 Name: Daniel P. Dickstein, M.D. FAAP Office Address: McLean Hospital PediMIND Program 115 Mill Street Mail Stop 321 Belmont MA 02478 Work Phone: 617-855-3939 Work Email: [email protected] Education: 09/1989- A.B/A.B. History and Judaic Studies Brown University Program in 05/1993 (double major) Liberal Medical Education (PLME, 8-year combined AB/MD Program) 09/1993- M.D. Medicine Brown University School of 05/1997 Medicine Postdoctoral Training: 07/1997- Triple Board Combined Pediatrics, Adult Brown University School of 06/2002 Residency Psychiatry, and Child Psychiatry Medicine Residency 07/01/2001- Chief Resident Combined Pediatrics, Adult Brown University School of 06/30/2002 Child Psychiatry Psychiatry, and Medicine Residency 07/01/2002- Clinical Research Pediatric Affective Neuroscience Pediatric and Developmental 04/01/2006 Fellow Mentors: Ellen Leibenluft M.D. Neuropsychiatry Branch and Daniel Pine M.D. National Institute of Mental Health Division of Intramural Research Programs (NIMH DIRP) Faculty Academic Appointments: 04/01/2006- Assistant Clinical Pediatric and National Institute of Mental 06/07/2007 Investigator Developmental Health Division of Intramural Neuropsychiatry Branch Research Programs (NIMH DIRP) 07/01/2007- Assistant Professor Psychiatry and Human Warren Alpert Medical 06/30/2011 Research Scholar Track Behavior (Primary), School of Brown University Pediatrics (Secondary) 07/01/2011- Associate Professor Psychiatry -

Accelerating Student Learning with High-Dosage Tutoring

EdResFoer Raecrocvehry ACCELERATING STUDENT LEARNING WITH HIGH-DOSAGE TUTORING EdResearch for Recovery Design Principles Series Carly D. Robinson, Matthew A. Kraft, & Susanna Loeb | Annenberg Institute at Brown University Beth E. Schueler | University of Virginia February 2021 EdResFoer Raecrocvehry DESIGN PRINCIPLES FOR EFFECTIVE TUTORING AT A GLANCE FREQUENCY GROUP SIZE Tutoring is most likely to be effective when Tutors can effectively instruct up to three or four delivered in high doses through tutoring programs students at a time. However, moving beyond this with three or more sessions per week or intensive, number can quickly become small group week-long, small-group programs taught by instruction, which is less personalized and requires talented teachers. a higher degree of skill to do well. One-to-one tutoring is likely most effective but also more costly. PERSONNEL FOCUS Because the skills required for tutoring are different Researchers have found tutoring to be effective at from the skills required for effective classroom all grade levels—even for high school students who teaching, a wide variety of tutors (including have fallen quite far behind. The evidence is volunteers and college students) can successfully strongest, with the most research available, for improve student outcomes, if they receive adequate reading-focused tutoring for students in early training and ongoing support. grades (particularly grades K-2) and for math- focused tutoring for older students. MEASUREMENT RELATIONSHIPS Tutoring programs that support data use and Ensuring students have a consistent tutor over time ongoing informal assessments allow tutors to more may facilitate positive tutor-student relationships effectively tailor their instruction for individual and a stronger understanding of students’ learning students. -

MADELINE WOKER Brown University Watson Institute (424) 382- 6408 Madeline [email protected]

MADELINE WOKER Brown University Watson Institute (424) 382- 6408 [email protected] EMPLOYMENT Watson Institute, Brown University Providence, RI Postdoctoral Fellow in International and Public Affairs July 2020- Summer 2022 EDUCATION Columbia University New York City, NY PhD in International and Global History (September 2020) Dissertation: Empire of inequality: the politics of taxation in the French colonial empire, 1900-1950s Advisor: Emmanuelle Saada Committee members: Susan Pedersen, Emmanuelle Saada, Adam Tooze, Vanessa Ogle, Thomas Piketty General Examinations fields: Debt, Taxation, and Power; French Empires; Comparative Empires; Colonial Southeast Asia University of Cambridge Cambridge, UK MPhil in Modern European History (with distinction) (June 2014) Thesis: The politics of taxation in the French Empire: the case of Indochina, 1897-1939 Advisor: Martin Daunton London School of Economics and Political Science London, UK MSc Politics and Government in the European Union Stream II: The International Relations of Europe (2011) Sciences Po Paris Paris, FR Master in European Affairs (2011) PEER-REVIEWED ARTICLES AND CHAPTERS “E. R. A. Seligman, initiator of global progressive public finance”, Journal of Global History, Volume 13, Issue 3, November 2018, pp. 352-373 “The cost of cheapness: the meaning of colonial “financial autonomy”” in Gurminder K. Bhambra and Julia McClure (Eds.) Imperial Inequalities: States, Empires, Taxation (Forthcoming, 2021) WORKING PAPERS “An imperial genealogy of international tax governance” OTHER PUBLICATIONS “Global Taxation Is a Mess. Here’s How to Start Fixing It.” The Nation, December 20, 2019 Madeline Woker “Quantitative Literacy for historians: who’s afraid of numbers?” (with Nicholas Mulder), Perspectives on History, Guest Blog, May 18, 2016 GRANTS, FELLOWSHIPS, AWARDS Max Weber postdoctoral fellowship, European University Institute (declined) Core Program Fellowship, Camargo Foundation, Cassis, France, Spring 2019 Visiting PhD researcher, University of California Los Angeles, Prof. -

CORPORATIONS and CAPITAL MARKETS EVOLUTION Sponsored

CORPORATIONS AND CAPITAL MARKETS EVOLUTION Sponsored by: Columbia Law School Transactional Studies Program Speaker Biographies Raanan A. Agus Raanan A. Agus is the global head of the Principal Strategies Group in the Equities Division of Goldman Sachs. The Principal Strategies Group is a proprietary, multi-strategy investment arm within Goldman Sachs that engages in equity long/short strategies, convertible arbitrage, volatility strategies, distressed and capital structure arbitrage, tactical trading, and special situation/event-driven strategies. Mr. Agus joined Goldman Sachs in 1993 as an associate in Equities Arbitrage, and became a managing director in 1999 and a partner in 2000. Mr. Agus is also a member of the Equities/FICC Joint Operating Committee and the Firmwide Risk Committee. He is also on the Goldman Sachs chess team. Mr. Agus earned an A.B. degree from Princeton University in 1989 and a joint J.D./M.B.A. degree, specializing in finance, from Columbia University in 1993. Alan L. Beller Alan L. Beller is a partner based in the New York office of Cleary Gottlieb Steen & Hamilton. His practice focuses on a wide variety of complex securities, corporate governance, and corporate matters. Mr. Beller served as the Director of the Division of Corporation Finance of the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission and as Senior Counselor to the Commission from January 2002 until February 2006. During his four-year tenure, Mr. Beller led the Division in producing the most far-reaching corporate governance, financial disclosure, and securities offering reforms in Commission history, including the implementation of the corporate provisions of the Sarbanes- Oxley Act of 2002 and the adoption of corporate governance standards for listed companies. -

THE RETURN of URBAN FISCAL CRISIS: Alternatives to Bankruptcy

THE RETURN OF URBAN FISCAL CRISIS: Alternatives to Bankruptcy Friday, November 1, 1-7pm. Salomon Center, 001, Main Green Saturday, November 2, 9am-2pm Rhode Island Hall, room 108, 60 George St. Co-sponsored by the Ford Foundation, the C. M. Culver Lectureship, the Harriet David Goldberg ‘56 Endowment and the Urban Studies Program “THE RETURN OF URBAN FISCAL CRISIS: ALTERNATIVES TO BANKRUPTCY” Co-sponsored by the Ford Foundation, the C. M. Culver Lectureship, the Harriet David Goldberg ‘56 Endowment, and the Urban Studies Program November 1, 2013 1:00 - 7:00 pm November 2, 2013 9:00 am - 2:00 pm Salomon Center – Main Green Rhode Island Hall – 60 George Street The Return of Urban Fiscal Crisis: Alternatives to Bankruptcy A conference co-sponsored by the Ford Foundation, the C.M. Culver Lectureship, the Harriet David Goldberg ’56 Endowment, and the Urban Studies Program of Brown University November 1 at 1 pm until November 2 at 2 pm The Great Recession has had huge repercussions for the fiscal condition of cities around the world. The US is experiencing another wave of municipal bankruptcies, and Rhode Island is not exempt. The impact of the economic crisis, delayed by the stimulus, has slowly worked its way down to the states and in turn, American cities. Vulnerable municipalities – with collapsing industries, high poverty, failed investments, over-indebtedness – tipped into insolvency. Central Falls, Rhode Island emerged from bankruptcy just as Detroit declared its own. This conference will convene scholars and practitioners from Rhode Island and beyond to discuss the causes of and alternatives to municipal bankruptcy under conditions of economic austerity. -

KIMBERLY KAY HOANG, PH.D. University of Chicago Department of Sociology 1126 E

Updated 01/2017 KIMBERLY KAY HOANG, PH.D. University of Chicago Department of Sociology 1126 E. 59th St. Chicago, IL 60637 [email protected]| 415-987-5112 ACADEMIC APPOINTMENTS 2015— Assistant Professor of Sociology and the College, University of Chicago Faculty Affiliate: Pozen Family Center for Human Rights, Faculty Board (2016-2019) Center for the Study of Race, Politics, and Culture Center for International Relations Center for the Study of Gender and Sexuality Committee on Southern Asian Studies 2013-2015 Assistant Professor, Department of Sociology, Boston College. 2011-2013 Postdoctoral Fellow at Rice University in Poverty, Justice, and Human Capabilities at the Center for Women, Gender, and Sexuality and the Kinder Institute for Urban Research EDUCATION Ph.D. Sociology with a Designated Emphasis in Women, Gender, and Sexuality University of California Berkeley, 2006 – 2011 Committee: Raka Ray (Chair), Barrie Thorne, Irene Bloemraad, Peter Zinoman Dissertation Title: New Economies of Sex and Intimacy in Vietnam * Winner of the 2012 American Sociological Association Best Dissertation Award M.A. Sociology, Stanford University, 2005-2006 B.A. Communication & Asian American Studies, University of California, Santa Barbara, 2001-2005, Summa Cum Laude * Winner of the Luis Leal Award for Undergraduate Research in the Social Sciences BOOKS 2015. Dealing in Desire: Asian Ascendancy, Western Decline, and the Hidden Currencies of Global Sex Work, Oakland, CA: University of California Press. Book Awards • National Women Studies Association Gloria E. Anzaldúa Book Prize, 2015. • SSSP Global Division Distinguished Book Award, 2016. 1 • American Sociological Association (ASA) Global & Transnational Sociology Best Scholarly Book Award, 2016. • ASA Sexualities Section Distinguished Book Award, 2016. -

Law School Record, Vol. 50, No. 2 (Spring 2004) Law School Record Editors

University of Chicago Law School Chicago Unbound The nivU ersity of Chicago Law School Record Law School Publications Spring 3-1-2004 Law School Record, vol. 50, no. 2 (Spring 2004) Law School Record Editors Follow this and additional works at: http://chicagounbound.uchicago.edu/lawschoolrecord Recommended Citation Law School Record Editors, "Law School Record, vol. 50, no. 2 (Spring 2004)" (2004). The University of Chicago Law School Record. Book 90. http://chicagounbound.uchicago.edu/lawschoolrecord/90 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Law School Publications at Chicago Unbound. It has been accepted for inclusion in The University of Chicago Law School Record by an authorized administrator of Chicago Unbound. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CON TEN T 5 SPRING 2004 All Too Human The Chicago Judges Project, the inaugural Chicago Policy Initiative, has released its and Lisa '04 first set of findings. Dean Levmore, Professor Cass Sunstein, Ellman, explain how appellate judges' findings appear to be influenced, and how the Policy ideas. Initiatives will bring to the world the power of the Law School's 6 Building the Rule of Law The fall of the Soviet Union didn't immediately deliver on its promise of freedom and justice for the former Soviet bloc. A surprising number of Law School alumni are a rule-of-law struggling there to create the infrastructure and mindset that underlay regime, something that most Central European and Eurasian nations have never known. 14 Student Life Students find that their study of the law takes them places they would never have expected. -

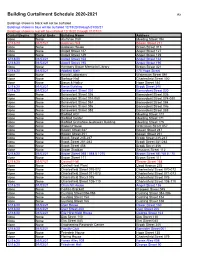

Building Curtailment Schedule 2020-2021 R2

Building Curtailment Schedule 2020-2021 R2 Buildings shown in black will not be curtailed Buildings shown in blue will be curtailed 12/18/20 through 01/03/21 Buildings shown in red will be curtailed 12/18/20 through 01/07/21 Curtail Begins Curtail Ends Building Name Address None None Alumnae Hall Meeting Street 194 12/18/20 01/07/21 Andrews Hall Bowen Street 211 None None Andrews House Brown Street 013 None None Angell Street 127 Angell Street 127 None None Angell Street 129 Angell Street 129 12/18/20 01/03/21 Angell Street 164 Angell Street 164 12/18/20 01/03/21 Angell Street 195 Angell Street 195 None None Annmary Brown Memorial Library Brown Street 021 12/18/20 01/03/21 Applied Math 170 Hope Street None None Arnold Laboratory Waterman Street 091 None None Barbour Hall Charlesfield Street 100 None None Barus & Holley Hope Street 184 12/18/20 01/03/21 Barus Building Brook Street 340 12/18/20 01/03/21 Benevolent Street 020 Benevolent Street 020 None None Benevolent Street 026 Benevolent Street 026 None None Benevolent Street 074-080 Benevolent Street 074-080 None None Benevolent Street 084 Benevolent Street 084 None None Benevolent Street 086 Benevolent Street 086 None None Benevolent Street 088 Benevolent Street 088 None None BioMed ACF Meeting Street 173 None None BioMed Center Meeting Street 171 None None BioMed Grimshaw-Gudewicz Building Meeting Street 175 None None Blistein House Waterman Street 057 None None Bowen Street 247 Bowen Street 247 None None Bowen Street 251 Bowen Street 251 None None Brook Street 245-247 Brook Street 245-247 -

Download Issue As

Important note: Please share this digital-only edition of Almanac with your colleagues. Read more. UNIVERSITY OF PENNSYLVANIA Tuesday June 2, 2020 Volume 66 Number 37 www.upenn.edu/almanac Thirteen Undergraduates: MindCORE Lila R. Gleitman Changes to the From the President Undergraduate Summer 2020 Penn Computer Connection Fellowships The Division of Business Services wishes to inform the Penn Community that as of June Statement on the With support 30, 2020, the Computer Connection’s retail Death of George Floyd from a $1 million gift store, located on the second floor of the Penn Once again our nation mourns. The from an anonymous Bookstore, will permanently close. tragic and senseless death of George donor, MindCORE The store has adapted to the many changes Floyd is a vivid reminder of the inequal- summer fellowships in the technology-retail market since it opened will now be named ities and unacceptable indignities that so 35 years ago, but the combined impact of nar- many of our citizens constantly endure. the Lila R. Gleitman rower margins, fewer new product releases, Undergraduate Sum- The events in Minneapolis this week and extraordinary mass-market discounting should lead everyone to recognize how mer Fellowships. strategies from large retailers, has had a pro- The endowed fellow- much more work our society must do to nounced impact on the store’s ability to sustain realize liberty and justice for all. As a ships program sup- its operation. ports up to 10 Penn nation we have much work to do. Going forward, the University remains com- While the entire Penn communi- undergraduate stu- mitted to providing resources and value-add- dents with summer Lila R. -

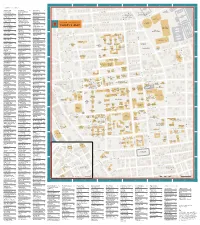

Campus Map 2005

S AV OY STR H.C. Hall EET Potter L E U N E V A Butler Hospital T F A T Taft Avenue Daycare E L M G R O V E Goddard A V E N U E Brown Stadium TREET SESSIONS S T E E R OBSERVATORY AVENUE T S E P O H Ladd Observatory DOYLE AVENUE F Management 1 2 3 4 5 6 campus listings Ó Facilities Admission Office C2 Ecology and D3 Judaic Studies E4 Management T Facilities (undergraduate) Evolutionary Biology 163 George Street E STREET KEEN H Ó Management Corliss-Brackett House Walter Hall A Brown Stadium Y (Elmgrove Ave. Ó Kassar House E4 E Ladd Observatory E R and Sessions St.) NU E Ó Advancement Office G1 Economics D2 151 Thayer Street (Hope St. S AV T and Doyle Ave.) YD T Facilities 110 Elm Street Robinson Hall E STR REET O KEEN H Ó L Management E L A Brown Stadium Pizzitola Keeney Quad F2 E Ó A Y (Elmgrove Ave. R E T Sports Center Ladd Observatory E L A R and Sessions St.) U A Africana Studies C3 Education Alliance for F2 N I (Hope St. E N S AV G T and Doyle Ave.) YD Churchill House Equity and Excellence King House E5 R LO T O E L H Pizzitola E N VENUE T Sports Center 154 Hope Street LLOYD A O Meehan in the Nation’s Schools BROWN UNIVERSITY A P V N B E Auditorium E Alumnae Hall B3 H N 222 Richmond Street R D AVENUE O Meehan LLOY S U L P O E B T Auditorium 194 Meeting Street Laboratories F1 E R R W S CAMPUS MAP O E T R for Molecular Medicine W Education D4 E E N E N T T Olney-MargoliesOlney-Margolies American Civilization D3 70 Ship Street S Barus Hall S Athletic Center T Athletic Center T R Norwood House R E Erickson E EET E R T BOWEN ST Athletic Complex -

Directory of Institutions in the United States and Canada with Pre-1600 Manuscript Holdings

Directory of Institutions in the United States and Canada with Pre-1600 Manuscript Holdings The Directory of Institutions is the first part of a continuation of the Census of Medieval and Renaissance Manuscripts in the United States and Canada, published in 1935 and 1937, and its 1962 Supplement.1 The present Directory details, when known, the current location of the collections listed in the original Census and Supplement, and identifies an additional 281 North American repositories of pre-1600 European manuscripts in Western languages that were not included in the earlier works. For all of the 475 North American repositories, this Directory provides updated contact data and general information on pre-1600 manuscript holdings. Detailed descriptions of individual manuscripts are outside the scope of this Directory, but bibliographical references to published catalogues and internet addresses giving access to on-line cataloguing records are provided when available. Following the organizational scheme of the original Census and Supplement, the Directory entries are organized alphabetically by State and City, with public collections listed first for each city, followed by private. (Due to privacy issues, modern private collections are not included). As in the original publications, the Canadian Provinces are found in a separate listing at the end of the directory. We would like to thank the hundreds of individuals who have contributed to this updated directory through their gathering and sharing of information regarding the whereabouts of pre- 1600 manuscripts in North American collections. To keep this information current, we ask that any updates or corrections be reported to us at [email protected].