Dissertation Proposal Submitted to the Dept

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Particulars of Some Temples of Kerala Contents Particulars of Some

Particulars of some temples of Kerala Contents Particulars of some temples of Kerala .............................................. 1 Introduction ............................................................................................... 9 Temples of Kerala ................................................................................. 10 Temples of Kerala- an over view .................................................... 16 1. Achan Koil Dharma Sastha ...................................................... 23 2. Alathiyur Perumthiri(Hanuman) koil ................................. 24 3. Randu Moorthi temple of Alathur......................................... 27 4. Ambalappuzha Krishnan temple ........................................... 28 5. Amedha Saptha Mathruka Temple ....................................... 31 6. Ananteswar temple of Manjeswar ........................................ 35 7. Anchumana temple , Padivattam, Edapalli....................... 36 8. Aranmula Parthasarathy Temple ......................................... 38 9. Arathil Bhagawathi temple ..................................................... 41 10. Arpuda Narayana temple, Thirukodithaanam ................. 45 11. Aryankavu Dharma Sastha ...................................................... 47 12. Athingal Bhairavi temple ......................................................... 48 13. Attukkal BHagawathy Kshethram, Trivandrum ............. 50 14. Ayilur Akhileswaran (Shiva) and Sri Krishna temples ........................................................................................................... -

Ac Name Ac Addr1 Ac Addr2 Ac Addr3 Ashiba Rep by Grand Mother & Ng Kunjumol,W/O Sulaiman, Uthiyanathel House,Punnyur P O

AC_NAME AC_ADDR1 AC_ADDR2 AC_ADDR3 ASHIBA REP BY GRAND MOTHER & NG KUNJUMOL,W/O SULAIMAN, UTHIYANATHEL HOUSE,PUNNYUR P O GEO P THOMAS 20/238, SHELL COLONY CHEMBUR,MUMBAI-71 RAJAN P C S/O CHATHAN PORUTHOOKARAN HOUSE THAZHEKAD , KALLATUKARA VARGHESE JOSE NALAPPATT HOUSE WEST ANGADI KORATTY PO 680308 KAVULA PALANCHERY PALLATH HOUSE KAVUKODE CHALISSERY. USHA GOPINATH KALLUNGAL HOUSE, KUNDALIYUR MARY SIMON CHIRANKANDATH HOUSE CHAVAKKAD ABUBACKR KARUKATHALA S/O KOCHUMON KARUKATHALA HOUSE EDATHIRINJI P O MADHUSUDHAN.R KOCHUVILA VEEDU,MANGADU. THOMAS P PONTHECKAL S/O P T PORINCHU PONTHECKAL HOUSE KANIMANGALAM P O RADHA K W/O KRISHNAN MASTER KALARIKKAL HOUSE P O PULINELLI KOTTAYI ANIL KUMAR B SREEDEVI MANDIRAM TC 27/1622 PATTOOR VANCHIYOOR PO JOLLY SONI SUNIL NIVAS KANJIRATHINGAL HOUSE P O VELUTHUR MATHAI K M KARAKAT HOUSE KAMMANA PO MANANTHAVADY MOHAMMED USMAN K N KUZHITHOTTIYIL HOUSE COLLEGE ROAD MUVATTUPUZHA. JOYUS MATHEW MANKUNNEL HOUSE THEKKEKULAM PO PEECHI ABHILASH A S/O LATE APPUKUTTAN LEELA SADANAM P O KOTTATHALA KOTTARAKARA ANTONY N J NEREKKERSERIJ HOUSE MANARSERY P O KANNAMALY BITTO V PAUL VALAPATTUKARAN HOUSE LOURDEPURAM TRICHUR 5 SANTHA LAWRENCE , NEELANKAVIL HOUSE, PERAMANGALAM.P.O. SATHIKUMAR B SHEELA NIVAS KATTUVILAKOM B S ROAD BSRA K 42 PETTAH PO TVM 24 MURALEEDHARAN KR KALAMPARAMBU HOUSE MELARKODE PO BEEPATHU V W/O SAIDALVI SAYD VILLA PERUNGJATTU THODIYIL HOUSE ASHAR T M THIRUVALLATH CHERUTHURUTHY P O THRISSUR DIST SHAHIDA T A D/O ALI T THARATTIL HOUSE MARATHU KUNNU ENKAKAD P O PRATHEEKSHA AYALKOOTTAM MANALI CHUNGATHARA P O AUGUSTINE -

Group Housing

LIST OF ALLOTED PROPERTIES DEPARTMENT NAME- GROUP HOUSING S# RID PROPERTY NO. APPLICANT NAME AREA 1 60244956 29/1013 SEEMA KAPUR 2,000 2 60191186 25/K-056 CAPT VINOD KUMAR, SAROJ KUMAR 128 3 60232381 61/E-12/3008/RG DINESH KUMAR GARG & SEEMA GARG 154 4 60117917 21/B-036 SUDESH SINGH 200 5 60036547 25/G-033 SUBHASH CH CHOPRA & SHWETA CHOPRA 124 6 60234038 33/146/RV GEETA RANI & ASHOK KUMAR GARG 200 7 60006053 37/1608 ATEET IMPEX PVT. LTD. 55 8 39000209 93A/1473 ATS VI MADHU BALA 163 9 60233999 93A/01/1983/ATS NAMRATA KAPOOR 163 10 39000200 93A/0672/ATS ASHOK SOOD SOOD 0 11 39000208 93A/1453 /14/AT AMIT CHIBBA 163 12 39000218 93A/2174/ATS ARUN YADAV YADAV YADAV 163 13 39000229 93A/P-251/P2/AT MAMTA SAHNI 260 14 39000203 93A/0781/ATS SHASHANK SINGH SINGH 139 15 39000210 93A/1622/ATS RAJEEV KUMAR 0 16 39000220 93A/6-GF-2/ATS SUNEEL GALGOTIA GALGOTIA 228 17 60232078 93A/P-381/ATS PURNIMA GANDHI & MS SHAFALI GA 200 18 60233531 93A/001-262/ATS ATUULL METHA 260 19 39000207 93A/0984/ATS GR RAVINDRA KUMAR TYAGI 163 20 39000212 93A/1834/ATS GR VIJAY AGARWAL 0 21 39000213 93A/2012/1 ATS KUNWAR ADITYA PRAKASH SINGH 139 22 39000211 93A/1652/01/ATS J R MALHOTRA, MRS TEJI MALHOTRA, ADITYA 139 MALHOTRA 23 39000214 93A/2051/ATS SHASHI MADAN VARTI MADAN 139 24 39000202 93A/0761/ATS GR PAWAN JOSHI 139 25 39000223 93A/F-104/ATS RAJESH CHATURVEDI 113 26 60237850 93A/1952/03 RAJIV TOMAR 139 27 39000215 93A/2074 ATS UMA JAITLY 163 28 60237921 93A/722/01 DINESH JOSHI 139 29 60237832 93A/1762/01 SURESH RAINA & RUHI RAINA 139 30 39000217 93A/2152/ATS CHANDER KANTA -

The Hindu : Friday Review Thiruvananthapuram / Personality : Demystifying a Musical Tradition

The Hindu : Friday Review Thiruvananthapuram / Personality : Demystifying a musical tradition Online edition of India's National Newspaper Friday, Nov 03, 2006 Vanitha Magazine in US Vanitha, Mahilaratnam, Balarama... Free Shipping. Shipped from US. www.bazaar9.com Friday Review Thiruvananthapuram Published on Fridays Features: Magazine | Literary Review | Life | Metro Plus | Open Page | Archives Education Plus | Book Review | Business | SciTech | Friday Review | Young Datewise Register to Vote World | Property Plus | Quest | Folio | Friday Review Bangalore Chennai and Tamil Nadu Delhi Hyderabad Classified Online Thiruvananthapuram Lead Support President Cinema Film Review Obama and help Music move America Dance forward. Start now. Theatre register.barackobama.co… Demystifying a musical tradition Arts & Crafts Heritage V. KALADHARAN Miscellany Kerala Joseph Palakkal, a scholar of ethnomusicology, has studied the craft and Houseboat content of liturgical practices of Syrian Christian music. News Packages News Update Get Budget Kerala Front Page Houseboat Tour National Packages. Ask our States: Experts Now ! • Tamil Nadu Incredible-India.com/Ho… • Andhra Pradesh • Karnataka • Kerala Publish Your • New Delhi Book • Other States Research International Opinion Publishing Companies Here. Business Sport Follow Just 3 Easy Miscellaneous Steps. Start Now Index SearchForPublishers.com Advts Download Classifieds Audiobooks Jobs Start your 30-Day Obituary Free Trial today. Over 100,000 titles PIONEERING WORK: Joseph Palakkal to choose from! "A piece of music may carry with it multiple stories of human interactions. In Audible.com the pursuit of making sense of melodies, musicologists have the privilege to see and discuss what others, including practitioners of music, may overlook. For instance, the layers of `inter-connectedness' between peoples and their respective histories that lie beneath the surface of sound structure. -

APL Details Unclaimed Unpaid Interim Dividend F.Y. 2019-2020

ALEMBIC PHARMACEUTICALS LIMITED STATEMENT OF UNCLAIMED/UNPAID INTERIM DIVIDEND FOR THE YEAR 2019‐20 AS ON 6TH APRIL, 2020 (I.E. DATE OF TRANSFER TO UNPAID DIVIDEND ACCOUNT) NAME ADDRESS AMOUNT OF UNPAID DIVIDEND (RS.) MUKESH SHUKLA LIC CBO‐3 KA SAMNE, DR. MAJAM GALI, BHAGAT 200.00 COLONEY, JABALPUR, 0 HAMEED A P . ALUMPARAMBIL HOUSE, P O KURANHIYOOR, VIA 900.00 CHAVAKKAD, TRICHUR, 0 RAJESH BHAGWATI JHAVERI 30 B AMITA 2ND FLOOR, JAYBHARAT SOCIETY 3RD ROAD, 750.00 KHAR WEST MUMBAI 400521, , 0 NALINI NATARAJAN FLAT NO‐1 ANANT APTS, 124/4B NEAR FILM INSTITUTE, 1000.00 ERANDAWANE PUNE 410004, , 0 ANURADHA SEN C K SEN ROAD, AGARPARA, 24 PGS (N) 743177, , 0 900.00 SWAPAN CHAKRABORTY M/S MODERN SALES AGENCY, 65A CENTRAL RD P O 900.00 NONACHANDANPUKUR, BANACKPUR 743102, , 0 PULAK KUMAR BHOWMICK 95 HARISHABHA ROAD, P O NONACHANDANPUKUR, 900.00 BARRACKPUR 743102, , 0 JOJI MATHEW SACHIN MEDICALS, I C O JUNCTION, PERUNNA P O, 1000.00 CHANGANACHERRY, KERALA, 100000 MAHESH KUMAR GUPTA 4902/88, DARYA GANJ, , NEW DELHI, 110002 250.00 M P SINGH UJJWAL LTD SHASHI BUILDING, 4/18 ASAF ALI ROAD, NEW 900.00 DELHI 110002, NEW DELHI, 110002 KOTA UMA SARMA D‐II/53 KAKA NAGAR, NEW DELHI INDIA 110003, , NEW 500.00 DELHI, 110003 MITHUN SECURITIES PVT LTD 1224/5 1ST FLOOR SUCHET CHAMBS, NAIWALA BANK 50.00 STREET, KAROL BAGH, NEW DELHI, 110005 ATUL GUPTA K‐2,GROUND FLOOR, MODEL TOWN, DELHI, DELHI, 1000.00 110009 BHAGRANI B‐521 SUDERSHAN PARK, MOTI NAGAR, NEW DELHI 1350.00 110015, NEW DELHI, 110015 VENIRAM J SHARMA G 15/1 NO 8 RAVI BROS, NR MOTHER DAIRY, MALVIYA 50.00 -

Accused Persons Arrested in Kozhikodu City District from 07.12.2014 to 13.12.2014

Accused Persons arrested in Kozhikodu city district from 07.12.2014 to 13.12.2014 Name of Name of the Name of the Place at Date & Arresting Court at Sl. Name of the Age & Cr. No & Sec Police father of Address of Accused which Time of Officer, Rank which No. Accused Sex of Law Station Accused Arrested Arrest & accused Designation produced 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 Cr.No.766/14 u/s 34/14 00.25 hrs 1 Maneeshkumar Saseendran Karamara, Eranhikkal Eranhikkal 279 IP, 185 of Elathur PS SI Sunilkumar Bailed by Police male 08/12/2014 MV Act Cr.No.767/14 u/s 40/14 21.30 hrs 2 Sunilkumar Balakrishnan Malayil, Thalakulathur Purakkattiri 279 IP, 185 of Elathur PS SI Sunilkumar Bailed by Police Male 08/12/2014 MV Act Cr.No.768/14 u/s 49/14 Kotteduth, 22.15 hrs 3 Dasappan Kunhachan Pooladikkunnu 279 IP, 185 of Elathur PS SI Sunilkumar Bailed by Police Male Perumthuruthi, Elathur 09/12/2014 MV Act Cr.No.769/14 u/s 35/14 Chengottumala, 22.20 hrs 4 Subhash Sundaran Karatt Paramba 279 IP, 185 of Elathur PS GASI Sivadasan Bailed by Police Male Purakkattiri 09/12/2014 MV Act Cr.No.770/14 u/s 32/14 Kokkadath, Kodakkad, 00.10 hrs 5 Aneeshkumar Kannan Puthiyangadi 279 IP, 185 of Elathur PS GASI Sivadasan Bailed by Police Male Vellachal, Kasargod 10/12/2014 MV Act Cr.No.772/14 u/s 54/14 Ambadi, Chengottumala 19.25hrs 6 Unnikrishnan Sekharan Nair Parmbath 279 IP, 185 of Elathur PS GSI Ismail Bailed by Police Male Colony, Thalakulathur 10/12/2014 MV Act Cr.No.773/14 u/s 42/14 23.15 hrs 7 Rameshbabu Raghavan Kambivalappil, Elathur Elathur 279 IP, 185 of Elathur PS GSI Surendran Bailed by Police Male 11/12/2014 MV Act Cr.No.707/14 u/s Bailed by Police 23/14 15.30 hrs 379 IPC & 20,21 8 Dikhilkumar Viswan Nellayil, Annassery Elathur PS Elathur PS SI Sunilkumar (Conditional Male 12/12/2014 of KPRB & RRS Bail) Act Cr.No. -

International Conference on Emerging Trends in Engineering, Science

International Conference on Emerging Trends in Engineering, Science and Technology (ICETEST – 2015) Procedia Technology Volume 24 Trissur, India 9 – 11 December 2015 Part 1 of 3 Editors: Chandramouli Viswanathan Sreerama Kumar-R ISBN: 978-1-5108-3639-6 Printed from e-media with permission by: Curran Associates, Inc. 57 Morehouse Lane Red Hook, NY 12571 Some format issues inherent in the e-media version may also appear in this print version. Copyright© by Elsevier B.V. All rights reserved. Printed by Curran Associates, Inc. (2017) For permission requests, please contact Elsevier B.V. at the address below. Elsevier B.V. Radarweg 29 Amsterdam 1043 NX The Netherlands Phone: +31 20 485 3911 Fax: +31 20 485 2457 http://www.elsevierpublishingsolutions.com/contact.asp Additional copies of this publication are available from: Curran Associates, Inc. 57 Morehouse Lane Red Hook, NY 12571 USA Phone: 845-758-0400 Fax: 845-758-2633 Email: [email protected] Web: www.proceedings.com TABLE OF CONTENTS PART 1 PREFACE ..............................................................................................................................................................................1 P. Vijayan, B. Jayanand, K. P. Indiradevi PREFACE TRACK: CEASIDE2015 ...................................................................................................................................6 N. Sajikumar IDENTIFICATION OF SUITABLE SITES FOR WATER HARVESTING STRUCTURES IN KECHERI RIVER BASIN ...................................................................................................................................................7 -

Ac Name Ac Addr1 Ac Addr2 Ac Addr3 Sunny Joseph Alias Varghese K Elayadathukudy House Thazhathoor Po, Kozhuvanawynad673595

AC_NAME AC_ADDR1 AC_ADDR2 AC_ADDR3 SUNNY JOSEPH ALIAS VARGHESE K ELAYADATHUKUDY HOUSE THAZHATHOOR P O, KOZHUVANAWYNAD673595 (VARGHESE K J) S T RAJALINGAM 18 E.M.M PILLAI-111 STREET CHENNIMALAI ROAD ERODE-638001 MINI JACOB MULLASSERIL HOUSE KADAMPANAD NORTH SANJU P R PANAYAMTHONDALIL THUVAYOOOR NORTH P O NELLIMUKAL NIJO MIGHEL KODIYAN HOUSE SANKARAIYER ROAD TRICHUR JOSEPH A V CHIEF MANAGER CSB,KOTTAYAM MOHANAN NAIR V AITTY KONAM M J BHAVAN THURUVICKAL P O MEDICAL COLLEGE PO TRIVANDRUM SURENDRAN V U S/O UNNIKRISHNAN VENKITANGU HOUSE CHETTUPUZHA ANUPA JOHN EMMATTY HOUSE GILGAL STREET KURA NELLIKKUNNU TRISSUR RAGUVARAN R 91,GANDHI NAGAR PALLAVAN SALAI CHENNAI 2 DINU K U KUNJALAKATTU HOUSE KAPPINCHAL CHERUKATTOOR P O JECCO ANTONY ROSE BHAVAN SOUTH KEERTHI NAGAR ROAD COCHIN 26 SAINUDHEEN KANJIRAMADATHIL HOUSE P.O.THOZHUVANNUR VIA.VALANCHERY SIMON CHERIAN 31.4TH CROSS JAI BHARATH NAGAR BANGALORE.560033 SHINNY SHAJI W/O SHAJI THOMAS KIZHAKKE PALANTHARA ERAVIPEROOR P.O. KASUMANI V S/O VELAN AKAMPADAM, POTHUNDY NEMMARA-678508 REJI K PETER KUDILIL HOUSE ENKAKAD P O ,MANGARA WADAKANCHERY SATHEESH R S/O RAMACHANDRAN KAIPPION KOLOUMB NANNIODE P O SAJEEVKUMAR S V S/O SASIKUMAR TC 14/1410,VIGNESWARA NAGAR,15,VAZHUTHACAUD,TRIVANDRUM DILEEP B PRADEEP MANDIRAM PUNTHALATHAZHAM KILIKOLLUR PO KOLLAM RAJAMMA K K LAKSHAM VEEDU-10 THONAKKAD P O CHERIYANAD BIJU M MOHANALAYAM PELA PO MAVELIKKAR-3 DR MOHAMED RAFEEQ K A KIZHAKKEY VEETIL EDAVILANGU P OITAL KODUNGALLUR THRISSUR DIST GEORGE JOSEPH MOONUTHOTTIYIL HOUSE VADAKKANIRAPPU NEEZHOOR RAMTIRATH V TIWARI SHIV SADAN BULDG, B-WING,1ST FLOOR,B-BULDG KATEMANIVALI,KALYAN,THANE-DT VEENA KUDUNBASREE WARD NO 2 PANDANAD PANCHAYATH PANDANAD PO LATHA 2199,III CROSS BASWESHWARA ROAD, MYSORE RAHIL LAKRA NEW DELHI 1 CH VISHNUVARDHAN 18-10-16,4TH LANE KEDARESWAPET,WARD NO 50 VIJAYAWADA-520002 RAJU.M. -

Kanyakumari Sl.No

KANYAKUMARI SL.NO. APPLICATION NO NAME AND ADDRESS K.VASUMATHI D/O KUMARAVEL 18/5C,NORTH ANJUKUDI 1 1204 ERUPPU, THANGAMPU THUR POST, KANYAKUMARI KUNA SEKAR.T S/O THANGAVEL 2 1205 ANNA NAGAR, ARALVOIMOZHY PO, KANYAKUMARI 629301 ARUN PRASAD.A S/O ARASAKUMAR 3 1206 4.55R SANGARALINGA PURAM, JAMES TOWN PO, KANYAKUMARI VIJAYA KUMAR.P S/O PHILIP ORUPANATHOTTU VILAI, 4 1207 MATHICODE, KAPPIYARAI POST, KANYAKUMARI 629156 JEEVA.S D/O SUBRAMANIAN 14 WEAVERS COLONY, 5 1208 VETTURNIMADAM POST, NAGERCOIL, KANYAKUMARI 629003 P.T.BHARATHI W/O S.GOPALAN 6 1209 55 PATTARIAR NEW ST, NAGERCOIL, KANYAKUMARI 629002 K.SELIN REENA D/O KUMARADHAS 7 1210 THUNDU VILAI VEEDU, VEEYANNOOR POST, KANYAKUMARI 629177 JEGANI.T D/O THANKARAJ VILAVOOR KUVARAVILAI, 8 1211 PARACODE, MULAGUMOODU PO, KANYAKUMARI Page 1 FELSY FREEDA.L D/O LAZER 9 1212 MALAANTHATTU VILAI, PALLIYADI POST, KANYAKUMARI 629169 CHRISTAL KAVITHA. R D/O RAJAN 10 1213 VALIYAVILAGAM HOUSE ST, MANKADU POST, KANYAKUMARI 629172 PRABHA.P D/O PADMANABHAN 11 1214 EATHENKADU, FRIDAYMARKET POST, KANYAKUMARI 629802 KALAI SELVI.N D/O NARAYANA PERUMAL 12 1215 THERIVILAI SWAMITHOPPU POST, KANYAKUMARI 629704 NAGALAKSHMI.M D/O MURUGESAN LEKSHMI BHAVAN, 13 1216 CHAKKIYANCODE, NEYYOOR POST, KANYAKUMARI 629802 BEULA.S D/O SATHIADHAS 14 1217 ANAN VILAI, KEEZHKULAM PO, KANYAKUMARI 629193 MAHESWARI.S D/O SIVACHANDRESWARAN 15 1218 1/20BTHEKKURICHI, RAJAKKAMANGALAM POST, KANYAKUMARI 629503 PREMALATHA.S W/O MURALIRAJ V.L, 460F-1, M.S.ROAD, 16 1219 SINGARATHOPPUPAR, VATHIPURAM, NAGERCOIL, KANYAKUMARI 629003 SUBASH.T S/O THANKAPPAN MANALI KATTU VILAI, 17 1220 PUTHEN VEEDU THICKA, NAMCODE PO, KANYAKUMARI 629804 Page 2 J. -

Kerala History Timeline

Kerala History Timeline AD 1805 Death of Pazhassi Raja 52 St. Thomas Mission to Kerala 1809 Kundara Proclamation of Velu Thampi 68 Jews migrated to Kerala. 1809 Velu Thampi commits suicide. 630 Huang Tsang in Kerala. 1812 Kurichiya revolt against the British. 788 Birth of Sankaracharya. 1831 First census taken in Travancore 820 Death of Sankaracharya. 1834 English education started by 825 Beginning of Malayalam Era. Swatithirunal in Travancore. 851 Sulaiman in Kerala. 1847 Rajyasamacharam the first newspaper 1292 Italiyan Traveller Marcopolo reached in Malayalam, published. Kerala. 1855 Birth of Sree Narayana Guru. 1295 Kozhikode city was established 1865 Pandarappatta Proclamation 1342-1347 African traveller Ibanbatuta reached 1891 The first Legislative Assembly in Kerala. Travancore formed. Malayali Memorial 1440 Nicholo Conti in Kerala. 1895-96 Ezhava Memorial 1498 Vascoda Gama reaches Calicut. 1904 Sreemulam Praja Sabha was established. 1504 War of Cranganore (Kodungallor) be- 1920 Gandhiji's first visit to Kerala. tween Cochin and Kozhikode. 1920-21 Malabar Rebellion. 1505 First Portuguese Viceroy De Almeda 1921 First All Kerala Congress Political reached Kochi. Meeting was held at Ottapalam, under 1510 War between the Portuguese and the the leadership of T. Prakasam. Zamorin at Kozhikode. 1924 Vaikom Satyagraha 1573 Printing Press started functioning in 1928 Death of Sree Narayana Guru. Kochi and Vypinkotta. 1930 Salt Satyagraha 1599 Udayamperoor Sunahadhos. 1931 Guruvayur Satyagraha 1616 Captain Keeling reached Kerala. 1932 Nivarthana Agitation 1663 Capture of Kochi by the Dutch. 1934 Split in the congress. Rise of the Leftists 1694 Thalassery Factory established. and Rightists. 1695 Anjengo (Anchu Thengu) Factory 1935 Sri P. Krishna Pillai and Sri. -

Selected N to Z.Pdf

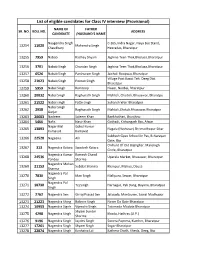

List of eligible candidates for Class IV interview (Provisional) NAME OF FATHER SR. NO. ROLL NO. ADDRESS CANDIDATE /HUSBAND'S NAME Naagendra Singh C-165, Indra Nagar, Naya Bus Stand, 13254 11020 Mahendra Singh Chaudhary Heeradas, Bharatpur 13255 7959 Nabab Radhey Shyam Jaghina Teen Thok,Bholuaa,Bharatpur 13256 3701 Nabab Singh Chandan Singh Jaghina Teen Thok,Bholuaa,Bharatpur 13257 6526 Nabab Singh Parshuram Singh Jaicholi Roopwas Bharatpur Village Post Kasot Teh. Deeg Dist. 13258 21023 Nabab Singh Pooran Singh Bharatpur 13259 5959 Nabal Singh Ramroop Naam, Nadbai, Bharatpur 13260 20032 Nabal Singh Raghunath Singh Mahtoli, Chaitoli, Bhusawar, Bharatpu 13261 21522 Nabal singh Fatte singh Suhansh Wair Bharatpur Nabal Singh 13262 2958 Raghunath Singh Mahtoli,Chetoli,Bhusawar,Bharatpur Gurjar 13263 20603 Nadeem Saleem Khan Bankhothari, Jhunjhnu 13264 5466 Nafis Nasir Khan Gothadi, Kishangarh Bas, Alwar Nagar Mal Gokul Kumar 13265 13893 Nagala (Nathusar) Shrimadhopur Sikar Kumavat Kumavat Subhash Gyan School Ke Pas, B-Narayan 13266 22528 Nageena Alli Gate, Btp Onfront Of Old Bijalighar, Mansingh 13267 313 Nagendra Katara Swadesh Katara Circle, Bharatpur Nagendra Kumar Ramesh Chand 13268 24536 Uparala Market, Bhusawar, Bharatpur Pandey Sharma Nagendra Mohan 13269 21153 Subalal Sharma Khanpur, Mahua, Dausa Sharma Nagendra Pal 13270 7830 Man Singh Malipura, Sewar, Bharatpur Singh Nagendra Pal 13271 18730 Tej Singh Harnagar, Pali Dang, Bayana, Bharatpur Singh 13272 2762 Nagendra Sen Girraj Prasad Sen Jatwada, Mantaown, Sawai Madhopur 13273 21223 -

LANTERN (Happiness Index) {Iaoicn¡ M³ Ahà Diocese of Kalyan, Xocpam\N¨P

APRIL - MAY 2017 FAMILYOur Traditions kt´mjw XoÀ¯pw Bß\njvTamWv. Htc Imcyw Xpeyamb Afhn cv t]sc Hcp t]mse kt´mjn¸n¡Wsa¶nÃ. AXpsImmWv Ncn{XmXoX Imew apX kt´mjsa¶ kakybv¡v XmXznIcpw At\zjIcpw Aeª psImncp¶Xv. PATRON ‘Happiness index’ Bishop Mar Thomas Elavanal hfsc ASp¯ Imew hsc `mcX¯nsâ A£ mwitcJIsf CHAIRMAN kv]Àin¨ncp¶nÃ. XnbädpIfnse ‘BcmWv Msgr. Emmanuel Kadankavil kt´mjw B{Kln¡m¯Xv?’ F¶mcw`n¡p¶ ]ckyw t]msebmbncp¶p AXv. CHIEF EDITOR ]mivNmXytemIw kt´mjw tXSnbpw Fr. Sheen Chittatukara AXf¡ m\pff amÀ¤§ fpw tXSnbeª p. 2012, ASSOCIATE EDITOR Pq¬ 28\v sFIycmjv{S kwLS\ AsXmcp Fr. Jomet Vazhayil a\pjymhImiambn {]Jym]n¨p. AXntesd ]cnKWnt¡ Xv, sPbnwkv CÃy³, ‘World EDITORIAL BOARD Happiness Day’ kvYm]Isâ ]ivNm¯eamWv. Fr. Jacob Porathur Fr. Benny Thanninilkumthadathil CXn\v 32 hÀj§Ä¡ v ap³]v, sPbnwkv Fr. Liju Keetickal Hcm\mY\mbncp¶p. I¡«bnse sXcphn Mrs. Rosily Thomas \n¶v aZÀ sXsckbpsS anj\dnamÀ Miss Annrary Thekiniath hfÀ¯nsbSp¯bmÄ. ]n¶oSv Abmsf A¶m Mr. Biju Dominic Fs¶mcp kv{Xo Z¯v FSp¡pIbpw Dr. C. P. Johnson XpSÀ¶bmÄ sFIycmjv{Sk`bnse Mr. Roy J. Kottaram Mr. Babu Mathew D]tZjvSmhpambn. Mr. Joseph Chittilapilly temI ‘kt´mj’ cmPy]«nIbn t\mÀshbpw sU³amÀ¡ pw, sFkvem³Upw ap³\ncbn MARKETING MANAGERS \n¡ pt¼mÄ C´ybpsS kvYm\w Fr. Sebastian Mudakkalil {ioe¦bv¡ pw AÀta\nbv¡pw Xmsg Mr. Roy Philip 122þmwaXmWv. Bdv {]Ym\ Imcy§fmbncp¶p CIRCULATION MANAGER AhÀ NÀ¨ sNbvXXv; Social Support, Freedom Fr.