JMS 70 1 095-101 Res Notes FINA

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

National Monitoring Program for Biodiversity and Non-Indigenous Species in Egypt

UNITED NATIONS ENVIRONMENT PROGRAM MEDITERRANEAN ACTION PLAN REGIONAL ACTIVITY CENTRE FOR SPECIALLY PROTECTED AREAS National monitoring program for biodiversity and non-indigenous species in Egypt PROF. MOUSTAFA M. FOUDA April 2017 1 Study required and financed by: Regional Activity Centre for Specially Protected Areas Boulevard du Leader Yasser Arafat BP 337 1080 Tunis Cedex – Tunisie Responsible of the study: Mehdi Aissi, EcApMEDII Programme officer In charge of the study: Prof. Moustafa M. Fouda Mr. Mohamed Said Abdelwarith Mr. Mahmoud Fawzy Kamel Ministry of Environment, Egyptian Environmental Affairs Agency (EEAA) With the participation of: Name, qualification and original institution of all the participants in the study (field mission or participation of national institutions) 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS page Acknowledgements 4 Preamble 5 Chapter 1: Introduction 9 Chapter 2: Institutional and regulatory aspects 40 Chapter 3: Scientific Aspects 49 Chapter 4: Development of monitoring program 59 Chapter 5: Existing Monitoring Program in Egypt 91 1. Monitoring program for habitat mapping 103 2. Marine MAMMALS monitoring program 109 3. Marine Turtles Monitoring Program 115 4. Monitoring Program for Seabirds 118 5. Non-Indigenous Species Monitoring Program 123 Chapter 6: Implementation / Operational Plan 131 Selected References 133 Annexes 143 3 AKNOWLEGEMENTS We would like to thank RAC/ SPA and EU for providing financial and technical assistances to prepare this monitoring programme. The preparation of this programme was the result of several contacts and interviews with many stakeholders from Government, research institutions, NGOs and fishermen. The author would like to express thanks to all for their support. In addition; we would like to acknowledge all participants who attended the workshop and represented the following institutions: 1. -

A Hitherto Unnoticed Adaptive Radiation: Epitoniid Species (Gastropoda: Epitoniidae) Associated with Corals (Scleractinia)

Contributions to Zoology, 74 (1/2) 125-203 (2005) A hitherto unnoticed adaptive radiation: epitoniid species (Gastropoda: Epitoniidae) associated with corals (Scleractinia) Adriaan Gittenberger and Edmund Gittenberger National Museum of Natural History, P.O. Box 9517, NL 2300 RA Leiden / Institute of Biology, University Leiden. E-mail: [email protected] Keywords: Indo-Pacific; parasites; coral reefs; coral/mollusc associations; Epitoniidae;Epitonium ; Epidendrium; Epifungium; Surrepifungium; new species; new genera; Scleractinia; Fungiidae; Fungia Abstract E. sordidum spec. nov. ....................................................... 155 Epifungium gen. nov. .............................................................. 157 Twenty-two epitoniid species that live associated with various E. adgranulosa spec. nov. ................................................. 161 hard coral species are described. Three genera, viz. Epidendrium E. adgravis spec. nov. ........................................................ 163 gen. nov., Epifungium gen. nov., and Surrepifungium gen. nov., E. adscabra spec. nov. ....................................................... 167 and ten species are introduced as new to science, viz. Epiden- E. hartogi (A. Gittenberger, 2003) .................................. 169 drium aureum spec. nov., E. sordidum spec. nov., Epifungium E. hoeksemai (A. Gittenberger and Goud, 2000) ......... 171 adgranulosa spec. nov., E. adgravis spec. nov., E. adscabra spec. E. lochi (A. Gittenberger and Goud, 2000) .................. -

Primeras Páginas 3 Copia.Qxp

Astroides.qxp 14/6/12 09:49 Página 207 Graellsia, 68(1): 207-218 enero-junio 2012 ISSN: 0367-5041 doi:10.3989/graellsia.2012.v68.057 SLIGHT GENETIC DIFFERENTIATION BETWEEN WESTERN AND EASTERN LIMITS OF ASTROIDES CALYCULARIS (PALLAS, 1776) (ANTHOZOA, SCLERACTINIA, DENDROPHYLLIIDAE) DISTRIBUTION INFERRED FROM COI AND ITS SEQUENCES P. Merino-Serrais1, P. Casado-Amezúa1, Ó. Ocaña2, J. Templado1 & A. Machordom1* ABSTRACT P. Merino-Serrais, P. Casado-Amezúa, Ó. Ocaña, J. Templado & A. Machordom. 2012. Slight genetic differentiation between western and eastern limits of Astroides calycularis (Pallas, 1776) (Anthozoa, Scleractinia, Dendrophylliidae) distribution inferred from COI and ITS sequences. Graellsia, 68(1): 207-218. Understanding population genetic structure and differentiation among populations is use- ful for the elaboration of management and conservation plans of threatened species. In this study, we use nuclear and mitochondrial markers (internal transcribed spacers -ITS and cytochrome oxidase subunit one -COI) for phylogenetics and nested clade analyses (NCA), thus providing the first assessment of the genetic structure of the threatened Mediterranean coral Astroides calycularis (Pallas, 1766), based on samples from 12 localities along its geo- graphic distribution range. Overall, we found no population differentiation in the westernmost region of the Mediterranean; however, a slight differentiation was observed when comparing this region with the Tyrrhenian and Algerian basins. Keywords: Threatened coral; population genetic structure; Mediterranean Sea. RESUMEN P. Merino-Serrais, P. Casado-Amezúa, Ó. Ocaña, J. Templado & A. Machordom. 2012. Leve diferenciación genética entre los límites occidental y oriental de distribución de Astroides calycularis (Pallas, 1776) (Anthozoa, Scleractinia, Dendrophylliidae), inferida a partir de secuencias de COI e ITS. -

INDEPENDENT STUDY: Module 2, Class 20

Hello Students, I am always seeking ways to improve these lessons. With some of the links no longer available, I wanted to credit them for the information I found at the time they were on the internet. My solution is a new color code. For sites that are no longer available, but were the source of information in the transcript, I have added an orange highlight with blue text. Also, there is another homework below, but you only have to choose one shell in question 1 and question 5. Sending Seashell Blessings! Shell INDEPENDENT STUDY: Module 2, Class 20 Please note: The pictures and comments in the transcript and recording below have been gathered over many years and where possible, I attribute them to their original source. If anyone connected with these photographs or comments would like them removed, please notify me and I will be happy to comply. The video recording of Class 20 is around 25 minutes long. Class 20: Shell #s 99,70,73,91, 98, 104 In recent lessons, we have undertaken an exploration of the diverse ways shells interact with man. We covered religion, medicine, artists, and jewelers, and we were just touching on architecture. Inspired by the incredible shapes created by mollusks for their seashell homes, man has been influenced to construct pagodas in the orient, and a remarkable opera house in Australia. Let’s see how the shells worked their architectural magic in the USA. This is a Thatcheria, also called by the common name of Japanese Wonder Shell. It is shell #99 in Ocean Oracle, and its meaning is “Respect.” Due to its quite unusual structure, when the first Thatcheria was discovered it was considered to be a freak of nature, a “monstrosity”. -

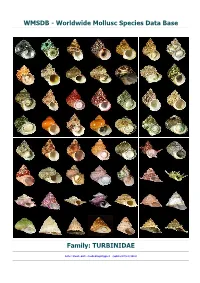

WMSDB - Worldwide Mollusc Species Data Base

WMSDB - Worldwide Mollusc Species Data Base Family: TURBINIDAE Author: Claudio Galli - [email protected] (updated 07/set/2015) Class: GASTROPODA --- Clade: VETIGASTROPODA-TROCHOIDEA ------ Family: TURBINIDAE Rafinesque, 1815 (Sea) - Alphabetic order - when first name is in bold the species has images Taxa=681, Genus=26, Subgenus=17, Species=203, Subspecies=23, Synonyms=411, Images=168 abyssorum , Bolma henica abyssorum M.M. Schepman, 1908 aculeata , Guildfordia aculeata S. Kosuge, 1979 aculeatus , Turbo aculeatus T. Allan, 1818 - syn of: Epitonium muricatum (A. Risso, 1826) acutangulus, Turbo acutangulus C. Linnaeus, 1758 acutus , Turbo acutus E. Donovan, 1804 - syn of: Turbonilla acuta (E. Donovan, 1804) aegyptius , Turbo aegyptius J.F. Gmelin, 1791 - syn of: Rubritrochus declivis (P. Forsskål in C. Niebuhr, 1775) aereus , Turbo aereus J. Adams, 1797 - syn of: Rissoa parva (E.M. Da Costa, 1778) aethiops , Turbo aethiops J.F. Gmelin, 1791 - syn of: Diloma aethiops (J.F. Gmelin, 1791) agonistes , Turbo agonistes W.H. Dall & W.H. Ochsner, 1928 - syn of: Turbo scitulus (W.H. Dall, 1919) albidus , Turbo albidus F. Kanmacher, 1798 - syn of: Graphis albida (F. Kanmacher, 1798) albocinctus , Turbo albocinctus J.H.F. Link, 1807 - syn of: Littorina saxatilis (A.G. Olivi, 1792) albofasciatus , Turbo albofasciatus L. Bozzetti, 1994 albofasciatus , Marmarostoma albofasciatus L. Bozzetti, 1994 - syn of: Turbo albofasciatus L. Bozzetti, 1994 albulus , Turbo albulus O. Fabricius, 1780 - syn of: Menestho albula (O. Fabricius, 1780) albus , Turbo albus J. Adams, 1797 - syn of: Rissoa parva (E.M. Da Costa, 1778) albus, Turbo albus T. Pennant, 1777 amabilis , Turbo amabilis H. Ozaki, 1954 - syn of: Bolma guttata (A. Adams, 1863) americanum , Lithopoma americanum (J.F. -

The Reproduction of the Red Sea Coral Stylophora Pistillata

MARINE ECOLOGY PROGRESS SERIES Vol. 1, 133-144, 1979 - Published September 30 Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. The Reproduction of the Red Sea Coral Stylophora pistillata. I. Gonads and Planulae B. Rinkevich and Y.Loya Department of Zoology. The George S. Wise Center for Life Sciences, Tel Aviv University. Tel Aviv. Israel ABSTRACT: The reproduction of Stylophora pistillata, one of the most abundant coral species in the Gulf of Eilat, Red Sea, was studied over more than two years. Gonads were regularly examined using histological sections and the planula-larvae were collected in situ with plankton nets. S. pistillata is an hermaphroditic species. Ovaries and testes are situated in the same polyp, scattered between and beneath the septa and attached to them by stalks. Egg development starts in July preceding the spermaria, which start to develop only in October. A description is given on the male and female gonads, their structure and developmental processes. During oogenesis most of the oocytes are absorbed and usually only one oocyte remains in each gonad. S. pistillata broods its eggs to the planula stage. Planulae are shed after sunset and during the night. After spawning, the planula swims actively and changes its shape frequently. A mature planula larva of S. pistillata has 6 pairs of complete mesenteries (Halcampoides stage). However, a wide variability in developmental stages exists in newly shed planulae. The oral pole of the planula shows green fluorescence. Unique organs ('filaments' and 'nodules') are found on the surface of the planula; -

Sexual Reproduction of the Solitary Sunset Cup Coral Leptopsammia Pruvoti (Scleractinia: Dendrophylliidae) in the Mediterranean

Marine Biology (2005) 147: 485–495 DOI 10.1007/s00227-005-1567-z RESEARCH ARTICLE S. Goffredo Æ J. Radetic´Æ V. Airi Æ F. Zaccanti Sexual reproduction of the solitary sunset cup coral Leptopsammia pruvoti (Scleractinia: Dendrophylliidae) in the Mediterranean. 1. Morphological aspects of gametogenesis and ontogenesis Received: 16 July 2004 / Accepted: 18 December 2004 / Published online: 3 March 2005 Ó Springer-Verlag 2005 Abstract Information on the reproduction in scleractin- came indented, assuming a sickle or dome shape. We can ian solitary corals and in those living in temperate zones hypothesize that the nucleus’ migration and change of is notably scant. Leptopsammia pruvoti is a solitary coral shape may have to do with facilitating fertilization and living in the Mediterranean Sea and along Atlantic determining the future embryonic axis. During oogene- coasts from Portugal to southern England. This coral sis, oocyte diameter increased from a minimum of 20 lm lives in shaded habitats, from the surface to 70 m in during the immature stage to a maximum of 680 lm depth, reaching population densities of >17,000 indi- when mature. Embryogenesis took place in the coelen- viduals mÀ2. In this paper, we discuss the morphological teron. We did not see any evidence that even hinted at aspects of sexual reproduction in this species. In a sep- the formation of a blastocoel; embryonic development arate paper, we report the quantitative data on the an- proceeded via stereoblastulae with superficial cleavage. nual reproductive cycle and make an interspecific Gastrulation took place by delamination. Early and late comparison of reproductive traits among Dend- embryos had diameters of 204–724 lm and 290–736 lm, rophylliidae aimed at defining different reproductive respectively. -

THE LISTING of PHILIPPINE MARINE MOLLUSKS Guido T

August 2017 Guido T. Poppe A LISTING OF PHILIPPINE MARINE MOLLUSKS - V1.00 THE LISTING OF PHILIPPINE MARINE MOLLUSKS Guido T. Poppe INTRODUCTION The publication of Philippine Marine Mollusks, Volumes 1 to 4 has been a revelation to the conchological community. Apart from being the delight of collectors, the PMM started a new way of layout and publishing - followed today by many authors. Internet technology has allowed more than 50 experts worldwide to work on the collection that forms the base of the 4 PMM books. This expertise, together with modern means of identification has allowed a quality in determinations which is unique in books covering a geographical area. Our Volume 1 was published only 9 years ago: in 2008. Since that time “a lot” has changed. Finally, after almost two decades, the digital world has been embraced by the scientific community, and a new generation of young scientists appeared, well acquainted with text processors, internet communication and digital photographic skills. Museums all over the planet start putting the holotypes online – a still ongoing process – which saves taxonomists from huge confusion and “guessing” about how animals look like. Initiatives as Biodiversity Heritage Library made accessible huge libraries to many thousands of biologists who, without that, were not able to publish properly. The process of all these technological revolutions is ongoing and improves taxonomy and nomenclature in a way which is unprecedented. All this caused an acceleration in the nomenclatural field: both in quantity and in quality of expertise and fieldwork. The above changes are not without huge problematics. Many studies are carried out on the wide diversity of these problems and even books are written on the subject. -

STATE of BIODIVERSITY in the MEDITERRANEAN (2-3 P

UNEP(DEC)/MED WG.231/18 17 April 2003 ENGLISH MEDITERRANEAN ACTION PLAN Meeting of the MED POL National Coordinators Sangemini, Italy, 27 - 30 May 2003 STRATEGIC ACTION PROGRAMME GUIDELINES DEVELOPMENT OF ECOLOGICAL STATUS AND STRESS REDUCTION INDICATORS FOR THE MEDITERRANEAN REGION In cooperation with UNEP Athens, 2003 TABLE OF CONTENTS Pages 1. INTRODUCTION ......................................................................................................... 1 2. AIMS OF THE REPORT .............................................................................................. 2 3. STATE OF BIODIVERSITY IN THE MEDITERRANEAN............................................. 2 Species Diversity................................................................................................................. 2 Ecosystems/Communities .................................................................................................. 3 Pelagic ............................................................................................................................... 3 Benthic ............................................................................................................................... 4 4. ECOSYSTEM CHANGES DUE TO ANTHROPOGENIC IMPACT............................... 6 Microbial contamination...................................................................................................... 6 Industrial pollution .............................................................................................................. 6 Oil -

Evolution, Distribution, and Phylogenetic Clumping of a Repeated Gastropod Innovation

Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society, 2017, 180, 732–754. With 5 figures. The varix: evolution, distribution, and phylogenetic clumping of a repeated gastropod innovation NICOLE B. WEBSTER1* and GEERAT J. VERMEIJ2 1Department of Biological Sciences, University of Alberta, Edmonton, Alberta, Canada T6G 2E9 2Department of Earth and Planetary Sciences, University of California, Davis, CA 95616, USA Received 27 June 2016; revised 4 October 2016; accepted for publication 25 October 2016 A recurrent theme in evolution is the repeated, independent origin of broadly adaptive, architecturally and function- ally similar traits and structures. One such is the varix, a shell-sculpture innovation in gastropods. This periodic shell thickening functions mainly to defend the animal against shell crushing and peeling predators. Varices can be highly elaborate, forming broad wings or spines, and are often aligned in synchronous patterns. Here we define the different types of varices, explore their function and morphological variation, document the recent and fossil distri- bution of varicate taxa, and discuss emergent patterns of evolution. We conservatively found 41 separate origins of varices, which were concentrated in the more derived gastropod clades and generally arose since the mid-Mesozoic. Varices are more prevalent among marine, warm, and shallow waters, where predation is intense, on high-spired shells and in clades with collabral ribs. Diversification rates were correlated in a few cases with the presence of varices, especially in the Muricidae and Tonnoidea, but more than half of the origins are represented by three or fewer genera. Varices arose many times in many forms, but generally in a phylogenetically clumped manner (more frequently in particular higher taxa), a pattern common to many adaptations. -

The Family Epitoniidae (Mollusca: Gastropoda) in Southern Africa and Mozambique

Ann. Natal Mus. Vol. 27(1) Pages 239-337 Pietermaritzburg December, 1985 The family Epitoniidae (Mollusca: Gastropoda) in southern Africa and Mozambique by R. N. Kilburn (Natal Museum, Pietermaritzburg) ABSTRACT Eighty species belonging to 15 genera of Epitoniidae are recorded from southern Africa and Mozambique; of these, 37 are new species and 19 are new records for the region. New species: Acirsa amara-, Amaea (1 Amaea) krousma; A . (Amaea) foulisi; A . (Filiscala) youngi; Rulelliscala bombyx; Cycloscala gazae; Opaliopsis meiringnaudeae; Murdochella crispata; M. lobata; Obstopalia pseudosulcata; O. varicosa; Opalia (Pliciscala) methoria; Compressiscala transkeiana; Chuniscala rectilamellata; Epitonium (Epitonium) sororastra; E.(E.) jimpyae; E.(E.) sallykaicherae; E. (Hirtoscala) anabathmos; E. (Perlucidiscala) alabiforme; E. (Nitidiscala) synekhes; E. (Librariscala) parvonatrix; E. (Limiscala) crypticocorona; E. (L.) maraisi; E.(L.) psomion; E. (Parviscala) amiculum; E.(P.) climacotum; E.(P.) columba; E.(P.) harpago; E.(P.) mzambanum; E.(P.) repandum; E.(P.) repandior; E.(P.) tamsinae; E.(P.) thyraeum; E. (Labeoscala) brachyspeira; E. (Asperiscala) spyridion; E. (Foliaceiscala) falconi; E.(F.) lacrima; E. (Pupiscala) opeas. New genus: Rutelliscala, type species R. bom byx sp.n. New subgenus (of Epitonium): Librariscala, type species Scalaria millecostata Pease, 1861. New records: The genera Acirsa, Cycloscala, Opaliopsis, Murdochella, Obstopalia, Plastiscala, Compressiscala and Sagamiscala are recorded from southern Africa for the first time. New species records are: Cirsotrema (Cirsotrema) varicosa (Lamarck, 1822); C. (1 Rectacirsa) peltei (Viader, 1938); Amaea (s.I.) sulcata (Sowerby, 1844); Amaea (Acrilla) xenicima (MelviJl & Standen, 1903); Cycloscala hyalina (Sowerby, 1844); Opalia (Nodiscala) bardeyi (Jousseaume, 1912); O. (N.) attenuata (Pease, I860); O. (Pliciscala) mormulaeformis (Masahito, Kuroda & Habe, 1971); Amaea sulcata (Sowerby, 1844); Epitonium (Epitonium) syoichiroi Masahito & Habe, 1976; E. -

SURVEY of the LITERATURE on RECENT SHELLS from the RED SEA (Second Enlarged and Revised Edition)

TRITON 24 SEPTEMBER 2011 SUPPLEMENT 1 SURVEY OF THE LITERATURE ON RECENT SHELLS FROM THE RED SEA (second enlarged and revised edition) L.J. van Gemert *) Abstract: About 2,100 references are listed in the survey. Shells are being considered here as shell-bearing mollusks of the Gastropoda, Bivalvia and Scaphopoda. And the region covered is not only the Red Sea, but also the Gulf of Aden, including Somalia, and the Suez Canal, including Lessepsian species. Literature on fossils finds, especially from the Pliocene, Pleistocene and Holocene, is listed too. Introduction My interest in recent shells from the Red Sea dates from about 1996. Since then, I have been, now and then, trying to obtain information on this subject. Recently I decide to stop gathering information in a haphazard way and to do it more properly. This resulted in a survey of approximately 1,420 references (Van Gemert, 2010). Since then, this survey has been enlarged considerably and contains now approximately 2,100 references. They are presented here. Scope In principle every publication in which mollusks are reported to live or have lived in the Red Sea should be listed in the survey. This means that besides primary literature, i.e. articles in which researchers are reporting their finds for the first time, secondary and tertiary literature, i.e. reviews, monographs, books, etc are to be included too. These publications were written not only by a wide range of authors ranging from amateur shell collectors to profesional malacologists but also by people interested in other fields. This implies that not only malacological journals and books should be considered, but also publications from other fields or disciplines, such as environmental pollution, toxicology, parasitology, aquaculture, fisheries, biochemistry, biogeography, geology, sedimentology, ecology, archaeology, Egyptology and palaeontology, in which Red Sea shells are mentioned.