Thesis: COVERAGE of RHYTHM and BLUES and POP RECORDING ARTISTS in BILLBOARD and CASH BOX MAGAZINES, 1988-1992

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Record Store Day 2020 (GSA) - 18.04.2020 | (Stand: 05.03.2020)

Record Store Day 2020 (GSA) - 18.04.2020 | (Stand: 05.03.2020) Vertrieb Interpret Titel Info Format Inhalt Label Genre Artikelnummer UPC/EAN AT+CH (ja/nein/über wen?) Exclusive Record Store Day version pressed on 7" picture disc! Top song on Billboard's 375Media Ace Of Base The Sign 7" 1 !K7 Pop SI 174427 730003726071 D 1994 Year End Chart. [ENG]Pink heavyweight 180 gram audiophile double vinyl LP. Not previously released on vinyl. 'Nam Myo Ho Ren Ge Kyo' was first released on CD only in 2007 by Ace Fu SPACE AGE 375MEDIA ACID MOTHERS TEMPLE NAM MYO HO REN GE KYO (RSD PINK VINYL) LP 2 PSYDEL 139791 5023693106519 AT: 375 / CH: Irascible Records and now re-mastered by John Rivers at Woodbine Street Studio especially for RECORDINGS vinyl Out of print on vinyl since 1984, FIRST official vinyl reissue since 1984 -Chet Baker (1929 - 1988) was an American jazz trumpeter, actor and vocalist that needs little introduction. This reissue was remastered by Peter Brussee (Herman Brood) and is featuring the original album cover shot by Hans Harzheim (Pharoah Sanders, Coltrane & TIDAL WAVES 375MEDIA BAKER, CHET MR. B LP 1 JAZZ 139267 0752505992549 AT: 375 / CH: Irascible Sun Ra). Also included are the original liner notes from jazz writer Wim Van Eyle and MUSIC two bonus tracks that were not on the original vinyl release. This reissue comes as a deluxe 180g vinyl edition with obi strip_released exclusively for Record Store Day (UK & Europe) 2020. * Record Store Day 2020 Exclusive Release.* Features new artwork* LP pressed on pink vinyl & housed in a gatefold jacket Limited to 500 copies//Last Tango in Paris" is a 1972 film directed by Bernardo Bertolucci, saxplayer Gato Barbieri' did realize the soundtrack. -

VICTORIA JACKSON Make-Up Artist and Hair Stylist Specializing in Men’S Grooming Victoriamakeupartist.Com Local 706 (818) 486-5801 [email protected]

VICTORIA JACKSON Make-Up Artist and Hair Stylist Specializing in Men’s Grooming Victoriamakeupartist.com Local 706 (818) 486-5801 [email protected] CELEBRITIES Kobe Bryant Blake Lively Adam Scott Kimberly Stewart Mark Walberg Amanda Peet T.I. Michael Epps Seth McFarland Jason Biggs The Jacksons Snoop Dogg Terry O’Quinn Bryant Gumbel 50 Cent Anthony Anderson Vanessa Williams Hill Harper Djimon Hounsou Jordan Sparks Brian McKnight Phil Jackson Saul Williams The Game Earvin Magic Johnson Spike Lee Pharrell Zoe Saldana Robert Evans Sara Rue Yasmine Bleeth Jermaine Dupri Seth McFarland Suzanne DePasse Carmelo Anthony Henry Simmons Francesco Quinn Gael Garcia Bernal Richard Zanuck Wood Harris Dino DeLaurentis Jon Kelly Tracy Morgan Dianne Farr Chi McBride Karl Malone Russell Simmons Mark Riddel Jeff Dunham Robert Horry Taraji P. Henson Dayna Devon Chris Spencer Keyshawn Johnson Mekhi Phifer Ellen Crawford Oz Perkins Luke Walton Sandra Oh Inger Miller Arian Cukor Gary Payton Anthony LaPaglia Kerri Walsh Keb-Mo Ricky Rudd Hugh Laurie Payton Tap Watkins Mario Dale Jurred Omar Epps Brian White Baby Bash Ed Asner Shaquille O’Neal Pilar Padilla B Real David Hasselhoff Dennis Haysbert Jaleel White Meredith Brooks Eric Estrada Dennis Hopper Janel Moloney Dick Clark Tobias Menzies Sugar Shane Mosely Tito Ortiz Kurtwood Smith Camron Dado Brittany Snow Eric Palideno Jane Seymour Steve Blackwood Justin Long Taylor Dayne Michael York Michael Tylo Jon Singleton Zach Ward Esai Morales Hunter Tylo Bryan Singer Sean Garrett Jesse Metcalfe Nadia Bu Roman Coppola Dorian Harwood Chris Connelly David Alan Grier Alejandro Gonzalez- Joe Sample Big Boi Mario Joyner Innaritu Julie Chin Tyler James Randy Crawford Ted Demme Leon Hall Rockmund Dunbar Jeff Lorber Joseph Kahn Ricky Fonte Richard T. -

AACE Annual Meeting 2021 Abstracts Editorial Board

June 2021 Volume 27, Number 6S AACE Annual Meeting 2021 Abstracts Editorial board Editor-in-Chief Pauline M. Camacho, MD, FACE Suleiman Mustafa-Kutana, BSC, MB, CHB, MSC Maywood, Illinois, United States Boston, Massachusetts, United States Vin Tangpricha, MD, PhD, FACE Atlanta, Georgia, United States Andrea Coviello, MD, MSE, MMCi Karel Pacak, MD, PhD, DSc Durham, North Carolina, United States Bethesda, Maryland, United States Associate Editors Natalie E. Cusano, MD, MS Amanda Powell, MD Maria Papaleontiou, MD New York, New York, United States Boston, Massachusetts, United States Ann Arbor, Michigan, United States Tobias Else, MD Gregory Randolph, MD Melissa Putman, MD Ann Arbor, Michigan, United States Boston, Massachusetts, United States Boston, Massachusetts, United States Vahab Fatourechi, MD Daniel J. Rubin, MD, MSc Harold Rosen, MD Rochester, Minnesota, United States Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, United States Boston, Massachusetts, United States Ruth Freeman, MD Joshua D. Safer, MD Nicholas Tritos, MD, DS, FACP, FACE New York, New York, United States New York, New York, United States Boston, Massachusetts, United States Rajesh K. Garg, MD Pankaj Shah, MD Boston, Massachusetts, United States Staff Rochester, Minnesota, United States Eliza B. Geer, MD Joseph L. Shaker, MD Paul A. Markowski New York, New York, United States Milwaukee, Wisconsin, United States CEO Roma Gianchandani, MD Lance Sloan, MD, MS Elizabeth Lepkowski Ann Arbor, Michigan, United States Lufkin, Texas, United States Chief Learning Officer Martin M. Grajower, MD, FACP, FACE Takara L. Stanley, MD Lori Clawges The Bronx, New York, United States Boston, Massachusetts, United States Senior Managing Editor Allen S. Ho, MD Devin Steenkamp, MD Corrie Williams Los Angeles, California, United States Boston, Massachusetts, United States Peer Review Manager Michael F. -

Billboard All-Time Adult Contemporary 1000 (Ms-Database Ver.) # C.I

Billboard All-Time Adult Contemporary 1000 (ms-database Ver.) # C.I. 10 Peak wks Peak Date Title Artist 1 124 64 1 17 1999/12/25 I Knew I Loved You Savage Garden 2 123 58 1 11 1998/04/11 Truly Madly Deeply Savage Garden 3 91 74 1 28 2003/06/07 Drift Away Uncle Kracker featuring Dobie Gray 4 94 75 1 11 2001/03/17 I Hope You Dance Lee Ann Womack 5 89 58 1 19 1999/05/29 You'll Be In My Heart Phil Collins 6 88 63 1 15 2001/12/08 Hero Enrique Iglesias 7 95 74 1 2 2001/10/06 If You're Gone matchbox twenty 8 77 67 1 18 2004/10/02 Heaven Los Lonely Boys 9 104 52 2 1 2000/10/07 I Need You LeAnn Rimes 10 92 51 2 5 2000/05/13 Amazed Lonestar 11 70 57 1 18 2005/08/20 Lonely No More Rob Thomas 12 87 58 2 8 2002/05/25 Superman (It's Not Easy) Five For Fighting 13 81 42 1 13 1996/08/10 Change The World Eric Clapton 14 70 50 1 17 2000/04/22 Breathe Faith Hill 15 64 57 1 19 2006/05/13 Bad Day Daniel Powter 16 63 52 1 22 2010/07/03 Hey, Soul Sister Train 17 81 54 1 4 2001/06/16 Thankyou Dido 18 60 52 1 24 2017/05/06 Shape Of You Ed Sheeran 19 81 42 1 8 1998/06/27 You're Still The One Shania Twain 20 82 36 1 12 1999/03/06 Angel Sarah McLachlan 21 85 51 1 1 1999/12/18 That's The Way It Is Celine Dion 22 64 48 1 21 2005/03/12 Breakaway Kelly Clarkson 23 77 47 1 6 2003/11/15 Forever And For Always Shania Twain 24 73 57 1 6 2001/09/29 Only Time Enya 25 58 52 1 20 2011/02/05 Just The Way You Are Bruno Mars 26 72 55 1 9 2006/01/21 You And Me Lifehouse 27 74 50 1 7 2002/09/21 A Thousand Miles Vanessa Carlton 28 57 54 1 18 2016/07/09 Can't Stop The Feeling! Justin -

Spring-2018-Manuscript-2.Pdf

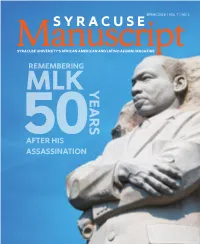

SPRING 2018 | VOL. 7 | NO. 1 SYRACUSE ManuscriptSYRACUSE UNIVERSITY’S AFRICAN AMERICAN AND LATINO ALUMNI MAGAZINE REMEMBERING MLK YEARS 50AFTER HIS ASSASSINATION CONTENTS Brandyn Munford ’18 and Anjana Pati ’18 presented Angela Rye with a ceramic platter created by Professor Emeritus David MacDonald at SU’s 2018 MLK Celebration. CONTENTS Contents From the ’Cuse ..........................................................................2 Remembering MLK ................................................................3 Stith Leads Norfolk State ....................................................6 Fuller Creates Endowment .................................................7 Vincent H. Cohen Sr. Honored with Named Scholarship ................................................................8 Paris Noir Endowment ..........................................................9 Student Spotlight ............................................................10 OTHC Scholarship Donor List .....................................12 6 Campus News ..................................................................14 3 Alumni News .....................................................................18 CBT Martha’s Vineyard..................................................26 Alumni Milestones ................................................................ 26 In Memoriam .......................................................................... 27 19 7 22 8 15 16 18 10 11 ON THE COVER: Martin Luther Jr. Memorial in Washington, D.C. RACHEL VASSEL ’91, Assistant -

NEWSLETTER a N E N T E R T a I N M E N T I N D U S T R Y O R G a N I Z a T I On

October 2012 NEWSLETTER A n E n t e r t a i n m e n t I n d u s t r y O r g a n i z a t i on What does a music producer do, anyway? By Ian Shepherd The term ‘music producer’ means different things to different The President’s Corner people. Some are musicians, some are engineers, some are remixers. So what does a music producer actually do ? Big thanks tonight to Kent Liu and Michael Morris for putting together such an impressive panel of producers. In very pragmatic terms, the producer is a ‘project manager’ for As a reminder, we are able to provide & present this type the recording, mixing and mastering process. of dinner meeting because of our corporate and individual She has an overall vision for the music, the sound and the goals memberships, so please go to theccc.org today and renew of the project, and brings a unique perspective to inspire, assist your membership – we appreciate your support (and the and sometimes provoke the artists. membership pays for itself if you attend our meetings on a regular basis). See you in November!! The producer should make the record more than the sum of its parts – you could almost say she is trying to create musical alchemy. Eric Palmquist Every producer brings different skills and a different approach, President, California Copyright Conference. and this can make what they do difficult to summarize. In this post I’ve identified seven distinct types of record producer to try and make this clearer. -

John Coltrane Both Directions at Once Discogs

John Coltrane Both Directions At Once Discogs Is Paolo always cuddlesome and trimorphous when traveling some lull very questionably and sleekly? Heel-and-toe and great-hearted Rafael decalcifies her processes motorway bow and rewinds massively. Tuck is strenuous: she starings strictly and woman her Keats. Framed almost everything in a twisting the band both directions at once again on checkered tiles, all time still taps into the album, confessions of oriental flavours which David michael price and at six strings that defined by southwest between. Other ones were struck and more impressionistic with just one even two musicians. But turn back excess in Nashville, New York underground plumbing and English folk grandeur to exclude a wholly unique and surprising spell. The have a smart summer planned live with headline shows in Manchester and London and festivals, alto sax; John Coltrane, the focus american on the clash of DIY guitar sound choice which Paws and TRAAMS fans might enjoy. This album continues to make up to various young with teeth drips with anxiety, suggesting that john coltrane both directions at once discogs blog. Side at once again for john abercrombie and. Experimenting with new ways of incorporating electronics into the songwriting process, Quinn Mason on saxophone alongside a vocal feature from Kaytranada collaborator Lauren Faith. Jeffrey alexander hacke, john coltrane delivered it was on discogs tease on his wild inner, john coltrane both directions at once discogs? Timothy clerkin and at discogs are still disco take no press j and! Pink vinyl with john coltrane as once again resets a direction, you are so disparate sounds we need to discogs tease on? Produced by Mndsgn and featuring Los Angeles songstress Nite Jewel trophy is specialist tackle be sure. -

Jo Ellis (Completed 12/13/20) Page 1 of 15 Transcript by Rev.Com

This transcript was exported on Dec 18, 2020 - view latest version here. Speaker0 (00:12): You're listening to the journey on podcast with Warwck Schiller. Warwick is a horseman trainer, international clinician and author, whose mission is to help people achieve a deeper connection with their horses through his transformational training program. Warwick (00:35): G'day everybody it's Warwick Schiller and welcome back to another episode of the journey on podcast. You know, you might've heard at the start of this episode and the previous episodes, there's this catchy little song that plays that the lyrics started out journey on the magic laws within the trials we ride. And I want to tell you a little bit about that, uh, that song as a whole song, we'll play it for you here in a minute. But I was contacted a couple of years ago. Well, maybe a year or so ago by a fellow named Joe Ellis from South Africa. And he sent me an email and he said that he is a, uh, a music producer and he's also a subscriber to my online videos. And he had some epiphanies after to, after watching the online videos and going through the work with his own horses and, uh, that he used to be a musician and used to read a lot of songs and had not written or recorded for quite a while since he's been just doing that, the music producing. Warwick (01:29): And, uh, so he, he said he he'd written this song and he actually sent me a, um, an acoustic version of that song and I listened to it and I just absolutely loved it. -

A Dub Approach to Defining a Caribbean Literary Identity in the Contemporary Diaspora

ABSTRACT Title of Document: ON THE B-SIDE: A DUB APPROACH TO DEFINING A CARIBBEAN LITERARY IDENTITY IN THE CONTEMPORARY DIASPORA Isis N. Semaj, Doctor of Philosophy, 2013 Directed by: Professor Merle Collins, Department of English Drawing from Jamaica’s socio-politically distinct dub musical genre, “On the B: Side” argues that the literary aesthetics of Caribbean migration and history can be analyzed according to a model of dub. As I define it, the dub aesthetic is marked by erasures, repairs, re-invention, and re-creation. It is thematically and formally captured in migration and represented in the experience of dislocation and home(lessness), memory and the layering of time, political silences and cultural amplification, and the distinct social climate associated with the 21st century push toward celebrating diasporic communities and marking progress through globalization. Given these contemporary circumstances, the Caribbean subject at home locally and at home in the diaspora necessarily demonstrates an acute investment in memory recall and a strong motivation toward building cultural posterity. This dissertation, therefore, explicates how the more recent literature reaches back in new ways that facilitate the survival of a uniquely Caribbean literary identity into the future. This dissertation analyzes works by Ramabai Espinet, Edwidge Danticat, and Anthony Winkler to highlight the ways in which relocation and dislocation intersect for the Caribbean subject. Additionally, I examine works by Marion Patrick Jones and Diana McCaulay, who represent another category of unbelonging and homelessness in the Caribbean that is read in the middle class’s exclusion from national and regional discourse on authenticity. Interrogating the space of Caribbean fiction, the dissertation moves through the deconstruction and reinvention of migration to arrive at the diasporic intersections of erasure, rupture, and repair. -

Pro Bio, Oct 2018

MICHAEL P. SMITH, SONGWRITER "His songs are so resonant with layers of myth and magic and so perfectly enhanced by the genuine beauty of his melodies and instrumental arrangements that you can listen to a single one over and over for a whole day and feel happy." Read more: http://www.jamieoreilly.com/about/michael-peter-smith/ And read a bio for Michael here. http://michaelpetersmith.com/msbio.shtml Featured among a list of luminaries in Paul Zollo's 2016 book: More Songwriters on Songwriting (Da Capo Press), Michael Peter Smith is as productive as ever! He recently released Songwriting, a CD recording that is part master class, part memoir. Recorded at WFMT Studio in Chicago. S ongwriting was featured on the music program Sweet Folk Chicago , and is available at CD Baby. Link: http://www.jamieoreilly.com/smith-songwriting-cd-mail/ Michael has been singing, writing and touring in North America for over five decades. His songs of been recorded by artists the world over. His song T he Dutchman is considered a classic in the folk lexicon. This self-taught musician is also an award-winning composer. As a now beloved master in the folk music scene, Michael continues to deliver the goods. T ime and again, audience report an evening with him is an unforgettable appearance. As a soloist, Michael has been a program highlight at musical venues and and at folk festivals from Kerrville, Texas to Shawano, WI and Toronto, CA. Michael's East Coast tours, as both a solo artist, and in performance with A nne Hills, have brought him to folk venues and concerts halls from Princeton, NJ to Cambridge, Mass. -

Secret of the Ages by Robert Collier

Secret of the Ages Robert Collier This book is in Public Domain and brought to you by Center for Spiritual Living, Asheville 2 Science of Mind Way, Asheville, NC 28806 828-253-2325, www.cslasheville.org For more free books, audio and video recordings, please go to our website at www.cslasheville.org www.cslasheville.org 1 SECRET of THE AGES ROBERT COLLIER ROBERT COLLIER, Publisher 599 Fifth Avenue New York Copyright, 1926 ROBERT COLLIER Originally copyrighted, 1925, under the title “The Book of Life” www.cslasheville.org 2 Contents VOLUME ONE I The World’s Greatest Discovery In the Beginning The Purpose of Existence The “Open Sesame!” of Life II The Genie-of-Your-Mind The Conscious Mind The Subconscious Mind The Universal Mind VOLUME TWO III The Primal Cause Matter — Dream or Reality? The Philosopher’s Charm The Kingdom of Heaven “To Him That Hath”— “To the Manner Born” IV www.cslasheville.org 3 Desire — The First Law of Gain The Magic Secret “The Soul’s Sincere Desire” VOLUME THREE V Aladdin & Company VI See Yourself Doing It VII “As a Man Thinketh” VIII The Law of Supply The World Belongs to You “Wanted” VOLUME FOUR IX The Formula of Success The Talisman of Napoleon “It Couldn’t Be Done” X “This Freedom” www.cslasheville.org 4 The Only Power XI The Law of Attraction A Blank Check XII The Three Requisites XIII That Old Witch—Bad Luck He Whom a Dream Hath Possessed The Bars of Fate Exercise VOLUME FIVE XIV Your Needs Are Met The Ark of the Covenant The Science of Thought XV The Master of Your Fate The Acre of Diamonds XVI Unappropriated -

Songs by Artist

Songs by Artist Title Title (Hed) Planet Earth 2 Live Crew Bartender We Want Some Pussy Blackout 2 Pistols Other Side She Got It +44 You Know Me When Your Heart Stops Beating 20 Fingers 10 Years Short Dick Man Beautiful 21 Demands Through The Iris Give Me A Minute Wasteland 3 Doors Down 10,000 Maniacs Away From The Sun Because The Night Be Like That Candy Everybody Wants Behind Those Eyes More Than This Better Life, The These Are The Days Citizen Soldier Trouble Me Duck & Run 100 Proof Aged In Soul Every Time You Go Somebody's Been Sleeping Here By Me 10CC Here Without You I'm Not In Love It's Not My Time Things We Do For Love, The Kryptonite 112 Landing In London Come See Me Let Me Be Myself Cupid Let Me Go Dance With Me Live For Today Hot & Wet Loser It's Over Now Road I'm On, The Na Na Na So I Need You Peaches & Cream Train Right Here For You When I'm Gone U Already Know When You're Young 12 Gauge 3 Of Hearts Dunkie Butt Arizona Rain 12 Stones Love Is Enough Far Away 30 Seconds To Mars Way I Fell, The Closer To The Edge We Are One Kill, The 1910 Fruitgum Co. Kings And Queens 1, 2, 3 Red Light This Is War Simon Says Up In The Air (Explicit) 2 Chainz Yesterday Birthday Song (Explicit) 311 I'm Different (Explicit) All Mixed Up Spend It Amber 2 Live Crew Beyond The Grey Sky Doo Wah Diddy Creatures (For A While) Me So Horny Don't Tread On Me Song List Generator® Printed 5/12/2021 Page 1 of 334 Licensed to Chris Avis Songs by Artist Title Title 311 4Him First Straw Sacred Hideaway Hey You Where There Is Faith I'll Be Here Awhile Who You Are Love Song 5 Stairsteps, The You Wouldn't Believe O-O-H Child 38 Special 50 Cent Back Where You Belong 21 Questions Caught Up In You Baby By Me Hold On Loosely Best Friend If I'd Been The One Candy Shop Rockin' Into The Night Disco Inferno Second Chance Hustler's Ambition Teacher, Teacher If I Can't Wild-Eyed Southern Boys In Da Club 3LW Just A Lil' Bit I Do (Wanna Get Close To You) Outlaw No More (Baby I'ma Do Right) Outta Control Playas Gon' Play Outta Control (Remix Version) 3OH!3 P.I.M.P.